ADA CLARE, QUEEN of BOHEMIA by Charles Warren Stoddard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 by BENJAMIN DE CASSERES

Boolcs and the Book World of The Sun, December 7, 1919. 15 Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 By BENJAMIN DE CASSERES. written, you know. I have just sent down ASTWARD the star of literary cm-- town for one of my books, want 'A J and I pire takes its way. After twenty-liv-e to paste a photograph as well as auto- years Ina Donna Coolbrith, crowned graph in it to mail to you. poet laureate of California by the Panama-P- "The old Oakland literary days! Do acific Exposition, has returned to yon know you were the first. one who ever New York. Her house on Russian Hill, complimented me on my choice of reading San Francisco, the aristocratic Olympus matter? Nobody at home bothered then-hea- of the Musaj of the Pacific slope, stands over what I read. I was an eager, empty. thirsty, hungry little kid and one day It is as though California had closed a k'Prsmmm mm m:mmm at the library I drew out a volume on golden page of literary and artistic mem- Pizzaro in Pern (I was ten years old). ories in her great epic for the life of You got the book and stamped it for me; Miss Coolbrith 'almost spans the life of and as you handed it to me you praised California itself. Her active and acuto me for reading books of that nature. , brain is a storehouse of memories and "Proud ! If you only knew how proud ' anecdote of those who have immortalized your words made me! For I thought a her State in literature Bret Harte, Joa- great deal of you. -

American Studies

american studies an interdisciplinary journal sponsored by the Midcontinent American Studies Association, the University of Kansas and the University of Missouri at Kansas City stuart levine, editor editorial board edward f. grief, English, University of Kansas, Chairman norm an r. yetman, American Studies, University of Kansas, Associate Editor William C Jones, College of Arts & Sciences, University of Missouri at Kansas City, Consulting Editor John braeman, History, University of Nebraska (1976) hamilton cravens. History, Iowa State University (1976) charles C. eldredge. History of Art, University of Kansas (1977) jimmie I. franklin. History, Eastern Illinois University (1977) robert a. Jones, Sociology, University of Illinois (1978) linda k. kerber, History, University of Iowa (1978) roy r. male, English, University of Oklahoma (1975) max j. skidmore, Political Science, Southwest Missouri State University (1975) officers of the masa president: Jules Zanger, English, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville vice-president: Hamilton Cravens, History, Iowa State University executive secretary: Norman H. Hostetler, American Studies, University of Nebraska editor: Stuart Levine, American Studies, University of Kansas copy editor and business manager: William A. Dobak editorial assistants: N. Donald Cecil, Carol Loretz Copyright, Midcontinent American Studies Association, 1974. Address business correspondence to the Business Manager and all editorial correspondence to the Editor. ON THE COVER: Top left, Selig Silvers tein's membership card in Anarchist Federation of America; top right, twenty seconds after bomb explosion in Union Square, New York City, March 28, 1908, Silverstein the bomb-thrower lies mortally wounded and a bystander lies dead; bottom, police at whom Silverstein attempted to throw bomb. See pages 55-78. -

Hclassification

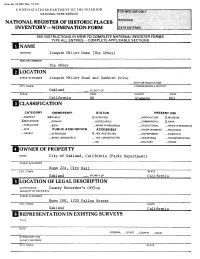

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Joaquin Miller Home (The Abbey) AND/OR COMMON The Abbey LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Joaquin Miller Road and Sanborn Drive _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Oakland _.. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 AT ameda 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XXPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM J^BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Oakland, California (Parks Department) STREET & NUMBER Room 224, City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Oakland VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE, County Recorder ! s Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER Room 100^ 1225 Fallen Street CITY. TOWN STATE Oakland California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE .FEDERAL _STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XXORIGINALSITE _MOVED DATE. X-GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Joaquin Miller House is a small three-part frame building at the foot of the steep hills East of Oakland California. Composed of three single rooms joined together, the so-called "Abbey" must be seen as the most provincial of efforts to impose gothic-revival detail upon the three rooms. -

The American Side of the Line: Eagle City's Origins As an Alaska Gold Rush Town As

THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town As Seen in Newspapers and Letters, 1897-1899 National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town National Park Service Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve 2019 Acknowledgments I want to thank the staff of the Alaska State Library’s Historical Collections, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives, the University of Washington’s Special Collections, and the Eagle Historical Society for caring for and making available the photographs in this volume. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska February 2019 Front Cover: Buildings in Eagle’s historic district, 2007. The cabin (left) dates from the late 1890s and features squared-off logs and a corrugated metal roof. The red building with clapboard siding was originally part of Ft. Egbert and was moved to its present location after the fort was decommissioned in 1911. Both buildings are owned by Dr. Arthur S. Hansen of Fairbanks. Photograph by Chris Allan, used with permission. Title Page Inset: Map of Alaska and Canada from 1897 with annotations in red from 1898 showing gold-rich areas. Note that Dawson City is shown on the wrong side of the international boundary and Eagle City does not appear because it does not yet exist. Courtesy of Library of Congress (G4371.H2 1897). Back Cover: Miners at Eagle City gather to watch a steamboat being unloaded, 1899. -

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives Grades: 7-HS Subjects: History, Oregon History, Civics, Social Studies Suggested Time Allotment: 1-2 class periods Lesson Background: Our impressions of events can often be influenced by the manner in which they are reported to us in the media. Begin by staging a class discussion of some recent news event(s) that have caused controversy. Can the students think of any news stories that strongly divide public opinions? Any that have been reported in a variety of different ways, depending on which television channels you watch or magazines you read? Can they think of examples where they thought one way or formed a certain opinion about a certain news event, only to have their minds change and opinion shift later, when more information came to light in the media? Moving on from this discussion, the lesson can demonstrate these issues of perspective. Lesson #1: Joaquin Miller—Genius or Cad? Joaquin Miller was the pen name of Cincinnatus Heine Miller, a colorful and controversial poet of the nineteenth century. (Read a detailed biography of Joaquin Miller on Wikipedia, here.) Known in his day as the ‘Poet of the Sierras,’ the ‘Byron of the Rockies,’ and the ‘Bard of Oregon,’ Miller became a celebrity throughout the United States, and especially in England. He was an associate of such enduring literary figures as Ambrose Bierce and Brett Hart. However, it could be argued that Miller’s fame came more from the popular image he created for himself—frontiersman, outdoorsman—than from the actual quality of his literary work. -

The Concordiensis, Volume 13, Number 5

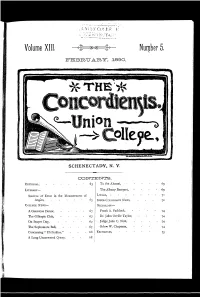

Volume XIIL Null)ber 5. FEERU ARY, :t890e @·--Union 2 F •JIZL .~IS~ SCHENECTADY,. Ne Y, ----·~----~----------~------ OOJSTTEN"TS_ EDITORIAL, To the Alumni, LITERARY- The .Albany Banquet, Sources of Error in the Measuren1ent of LOCALS,. - Ang~es, 65 INTER-COLLEGIATE NEWS, COLLEGE NEWS- NECROLO·GY-- A Generous Donor, Frank A. Paddock. 74 The Gillespie Club, Dr. }ohn Orville Taylor, 74 On Prayer Day, Judge ] ohn C. N ott, 74 The Sophomore Ball, Orlow W. Chapman, 74 Concerning "Eli Perkins," ExcHAN"G ES, 75 I A Long Unanswered Qnery11 !· UNION UNIVERSITY HARRISON E. \iVEBSTER, LL.D., President UNION COLLEGE,.. SCI-IENECTADY, N. Y. 1. CLASSICAL Cou.RsE~Tbe Classical Course is the usuall>a.<JGalaureate coU:rse of American colleges. Students may be permitted to pursue additional studies in either of the other courses. 2. ScniNTIFtc CouRsE--In the Scientific Course the mode:rn. languages are substituted for the ancient, and the amount of mathe matical and English studies is increased. 3. ScHooL OF CIVIL ENGINEERING-The student iu this department enjoys advantages nowhere surpassed in the course of in.struction, in its collection of models, in.strumen.ts and bo0ks~ ,tlte accumulation of many )ears by the late Professor Gillespie, and also in unusual facilities f<n· acquiring a practical knowledg,e ofbJ.strumental field work. 4. EcLECTIC CouRsE-An Eclectic Course, consisting of studies selected at pleasure from the preceding courses, may be taken by any one who, upon examination, is found qualified to pursue :it. On the completion of this a certificate of attainment will be given. There are also special courses in Analytical Chemistry, Metallll.rgy and Natural History. -

Confessions of an American Opium Eater : from Bondage to Freedom

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924090935077 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2001 GforttcU Uttlnetaitg ffiibrarg Stljaftt, !N*ni lock CHARLES WILUAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA aWD THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 laiB ''^.^^^-^ ) : Confessions American Opium Eater From Bondage to Freedom Timely advised, the coming evil shun Better not do the deed than weep it done. — Trior. BOSTON James H. Earle 178 Washington Street 1895 Copyright, i8gS, By James H. Earle. Ail rights reserved. OOI^TEZSTTS. CHAPTER I. Preliminary i CHAPTER II. Concerning My Early Life lo CHAPTER III. My First Experiment with Opium 24 CHAPTER IV. Am I My Sister's Keeper ?—The Prodigal Daughter ... 33 CHAPTER V. At the Gaming Table — The Death of My Wife .... 41 CHAPTER VI. I Attempt to Break Away from the Opium Habit, Do not Suc- ceed, and Return to Gambling 47 CHAPTER VII. "Who Fell Among Thieves"—A Startling Experience . 51 CHAPTER VIII. I Enter the Maine General Hospital as a Patient ... 56 CHAPTER IX. I Attempt to Fight the Demon Morphia Single-Handed and Am Defeated 63 II OOlTTEilsrT'S. (COHTISUEDA CHAPTER X. A Dishonorable Lawyer — I Advocate My Own Case . 73 CHAPTER XI. How I Was Living . .... 78 CHAPTER XII. I Believe in God and Christ, but Have No Religion . -

Maude Adams and the Mormons

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2013-1 Maude Adams and the Mormons J. Michael Hunter Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hunter, J. Michael, "Maude Adams and the Mormons" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1391. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1391 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mormons and Popular Culture The Global Influence of an American Phenomenon Volume 1 Cinema, Television, Theater, Music, and Fashion J. Michael Hunter, Editor Q PRAEGER AN IMPRI NT OF ABC-CLIO, LLC Santa Barbara, Ca li fornia • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2013 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mormons and popular culture : the global influence of an American phenomenon I J. Michael Hunter, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-39167-5 (alk. paper) - ISBN 978-0-313-39168-2 (ebook) 1. Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints-Influence. 2. Mormon Church Influence. 3. Popular culture-Religious aspects-Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

BETWEEN COCA and COCAINE: a Century Or More of U.S.-Peruvian Drug Paradoxes, 1860-1980

Number 251 BETWEEN COCA AND COCAINE: A Century or More of U.S.-Peruvian Drug Paradoxes, 1860-1980 Paul Gootenberg, with Commentary by Julio Cotler Professor Paul Gootenberg The Woodrow Wilson Center, Washington Latin American Program Department of History, SUNY-Stony Brook Copyright February 2001 This publication is one of a series of Working Papers of the Latin American Program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The series includes papers in the humanities and social sciences from Program fellows, guest scholars, workshops, colloquia, and conferences. The series aims to extend the Program's discussions to a wider community throughout the Americas, to help authors obtain timely criticism of work in progress, and to provide, directly or indirectly, scholarly and intellectual context for contemporary policy concerns. Single copies of Working Papers may be obtained without charge by writing to: Latin American Program Working Papers The Woodrow Wilson International Center One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars was created by Congress in 1968 as a "living institution expressing the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson, symbolizing and strengthening the fruitful relations between the world of learning and the world of public affairs." The Center's Latin American Program was established in 1977. LATIN AMERICAN PROGRAM STAFF Joseph S. Tulchin, Director Cynthia Arnson, Assistant Director Luis Bitencourt, Director, Brazil @ the -

Americana Bibliographies Books in All Fields

Sale 490 Thursday, October 11, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Literature - Americana Bibliographies Books in All Fields Auction Preview Tuesday, October 9, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, October 10, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, October 11, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

Literature in Rochester 1865 - 1905 by NATALIE F

Edited by DEXTER PERKINS, City HirtoGm and BLAKE MCKELVBY. Assistant City Hirtorian VOL. x JANUARY, 1948 No. 1 Literature in Rochester 1865 - 1905 By NATALIE F. HAWLEY At the end of the Civil War, Rochesterians-along with Americans elsewhere-became increasingly absorbed in the commercial and in- dustrial activities which were mushrooming all over the land. A city far different from the Yankee town of the fifties was developing along the Genesee. In the bustle of expansion, much of the old classical tradition was neglected and many conventional social patterns were outgrown. But in due course, increasing wealth, a new emphasis upon social events and social accomplishments, provided the occasion for an earnest, if somewhat indiscriminate search for culture. Social pretensions alone could not account for the revival of the literary arts however. The club movement, growing from a need to replace the inadequate social groups of earlier days, and accelerated by the increasing activity of women as society leaders, gave real nourishment to literary interests. It was in these social-literary clubs that the sober scholarship of local professors and theologians, at a discount for many years, worked best to provide a sound base for the creative and critical efforts of those newly awakened to the pleasures of literature. Out of an abundance of amorphous material, we have tried to choose those groups and individuals who most surely represent the significant trends and tastes of the period rather than to select our own favorites or to establish an arbitrary standard of the best which Roch- ester has contributed to prose and poetry.