Migration and Small Towns in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

The World Bank Shanxi Gas Utilization (P133531) REPORT NO.: RES41698 Public Disclosure Authorized RESTRUCTURING PAPER ON A PROPOSED PROJECT RESTRUCTURING OF SHANXI GAS UTILIZATION APPROVED ON MARCH 28, 2014 TO Public Disclosure Authorized PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ENERGY & EXTRACTIVES EAST ASIA AND PACIFIC Public Disclosure Authorized Regional Vice President: Victoria Kwakwa Country Director: Martin Raiser Regional Director: Ranjit J. Lamech Practice Manager/Manager: Jie Tang Task Team Leader(s): Ximing Peng Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Shanxi Gas Utilization (P133531) ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CHP Combined Heat and Power Covid-19 Corona Virus Disease -2019 CPS Country Partnership Strategy EA Environmental Assessment FYP Five Year Plan GoC Government of China IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development ICR Implementation Completion Review ISR Implementation Status and Results Report MOF Ministry of Finance PDO Project Development Objective PMO Project Management Office RE Renewable Energy RF Results Framework TA Technical Assistance The World Bank Shanxi Gas Utilization (P133531) Note to Task Teams: The following sections are system generated and can only be edited online in the Portal. BASIC DATA Product Information Project ID Financing Instrument P133531 Investment Project Financing Original EA Category Current EA Category Full Assessment (A) Full Assessment (A) Approval Date Current Closing Date 28-Mar-2014 30-Jun-2020 Organizations Borrower Responsible Agency International Department, Ministry of Finance -

Investigation and Suggestion on the Building Environment of Traditional Courtyard House

2018 International Conference on Advanced Chemical Engineering and Environmental Sustainability (ICACEES 2018) ISBN: 978-1-60595-571-1 Investigation and Suggestion on the Building Environment of Traditional Courtyard House in Ancient City of Pingyao Xiaoxing Han and Xiangdong Zhu ABSTRACT The ancient city of Pingyao is the world cultural heritage, it has a complete preservation of the wall, the Yamen, the temple as well as numerous traditional commercial shops and the dwelling house, it is the Chinese historical economic and cultural development real testimony. With the development of society, there are great changes in family structure and life style, and people's demand is more and more abundant. People living in traditional courtyard house need to improve their living facilities and building environment and improve their living comfort continuously. We need more exploration and research on how to preserve the authenticity and integrality of the heritage value, improve the living environment, improve the quality of life of the residents, and let the residents actively participate in the protection of the heritage and enjoy the achievements of the heritage protection through the restoration of the traditional courtyard house in the ancient city of Pingyao.1 KEYWORDS Ancient City of Pingyao, Traditional Courtyard House, Building Environment, Renewal and Transformation. BACKGROUND OVERVIEW The ancient city of Pingyao is located in Pingyao county, Jinzhong city, Shanxi province. It was first established during the Western Zhou Dynasty around 827-782 1Xiaoxing Han, Xiangdong Zhu, College of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China. 431 B.C. As a county—in its current location—it dates back to the Northern Wei Dynasty around 424-448 A.D. -

Rural-Urban Migration in China

Internal Labor Migration in China: Trends, Geographical Distribution and Policies Kam Wing Chan Department of Geography University of Washington Seattle [email protected] January 2008 Wuhan: Share of Migrant Workers (Non-Hukou) (2000 Census Data) Industry % of employment in that industry Manufacturing 43 Construction 56 Social Services 50 Real Estate and Housing 40 Wuhan City (7 city districts) 46 Urban recreation consumption rose at 14% p.a in 1995-2005 Topics • Hukou System and Migration Statistics • Migration Trends • Geography •Policies (The Household Registration System, 户口制度) • Formally set up in 1958 • Divided population/society into two major types of households: rural and urban • Differential treatments of rural and urban residents • Controlled by the police and other govt departments • Basically an “internal passport system” • Currently, the system serves as a benefit eligibility system; a tool of institutional exclusion than controlling geographical mobility • The population of a city is divided into “local” and “outside” population. Ad MIGRANT CHILDREN FALL THROUGH THE CRACKS An unlicensed school in Beijing Two types of internal migrants • Hukou Migrants: migrants with local residency rights • Non-hukou Migrant: migrants without local residency rights – also called: non-hukou population, or more generally, “floating population” Wuhan: Share of Non-Hukou Migrant Workers (2000 Census Data) Industry % of Employment Manufacturing 43 Construction 56 Social Services 50 Real Estate and Housing 40 Wuhan City (7 city districts) -

'Xiaohe 1': a New Walnut Cultivar with High Fruit Setting Rate Of

HORTSCIENCE 55(12):2047–2051. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15340-20 ing, androgenic type, and high yield, which are similar to the characteristics of ‘Xiaohe 1’. ‘Xiaohe 1’: A New Walnut Cultivar The cultivar Xiaohe 1 presented high- yielding potential despite late-frost incidents with High Fruit Setting Rate of after the initial budding. For example, after a province-wide late-frost incident in 2018, the Secondary Bud Germination after the cultivar Xiaohe 1 showed stronger resistance to below-freezing temperature, a higher fruit set rate after secondary emergence of acces- Harm of Late Frost sory and other buds, and better overall traits Jing Wu, Qi He, Caihong Zhang, and Gui Wang than the control cultivars Liaoning 1 and Shanxi Academy of Forestry Sciences, Taiyuan, Shanxi 030012, China Luguang. Additional index words. breeding, late frost hazard, secondary bud germination, walnut Description and Performance The tree stand of ‘Xiaohe 1’ is semi- Walnut (Juglans regia L.), a deciduous the Xinjiang Kashgar region, and in the dwarf, with a spreading growth habit and tree in the Juglandaceae family, is a forest central and southern parts of Shanxi Province moderate growth rate. The height of a 6- tree species that has a long cultivation history it caused freezing damage to walnut trees and year-old tree is four-fifths that of ‘Liaoning and wide distribution in China because of its decimated production in select areas (Liu 1’. The fruit branches are short and thick, economic importance (Pei and Lu, 2011). et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2007). The damage with an average length of 16.4 cm and an China accounts for more than 50% of the caused by late frost in 2013 resulted in average diameter of 0.9 cm. -

China's Urbanization, Social Restructure and Public

Graduate Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies 9:1 (2014) 55-77 Articles China’s Urbanization, Social Restructure and Public Administration Reforms: An Overview Xiaoyuan Wan University of Sheffield [email protected] Abstract This paper provides a review of the broad process of China’s urbanization and the urban public administration reform since the 1978 reforms, with a focus on the changing public policies in the realms of employment, housing, social insurance and the devolution of government authority. It suggests that the main government rationale of the public administration system reforms was to hand over a part of public services which used to be delivered by the central government and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), to local governments and to devolve a part of responsibility to the private sector, the social sector and individuals. According to these reforms, most of the social services, which could only be enjoyed by the employees of the SOEs were handed over to grassroots governments and aimed to cover more urban population. But at the same time, individuals had to take on more responsibilities of their careers choice and fund part of their own social welfare. This paper concludes by suggesting that with proliferating literature on China’s social and economic transition, further study should be carried out to explore the implementation of the reformed urban public policies by local governments and special concern should be given to the participation of non-government actors in China’s public administration. Introduction SINCE THE LATE 1970S, a series of economic reforms have been driving China to step away from a rigid socialism to a more open and diverse society, in which the urban economy developed at a tremendous speed and played an increasingly important role in the national economy. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD719 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$100 MILLION TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FOR A SHANXI GAS UTILIZATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized February 26, 2014 China and Mongolia Sustainable Development Unit Sustainable Development Department East Asia and Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective November 1, 2013) Currency Unit = RMB (Chinese Yuan Renminbi) US$ 1 = RMB 6.10 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS bcma Billion cubic meters per annum NDRC National Development and Reform Commission CBM Coal Bed Methane Nm3 Normal Cubic Meters CHP Combined Heat and Power NOx Nitrogen Oxides CNG Compressed Natural Gas PDO Project Development Objective DA Designated Account PMO Project Management Office EA Environmental Assessment QKNGC Qingxu Kaitong Natural Gas Company EHS Environmental, Health and Safety RAP Resettlement Action Plan EIA Environmental Impact RPF Resettlement Policy Framework Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return SCADA Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition EMP Environmental Management Plan SCPTC Shanxi CBM (Natural Gas) Pipeline -

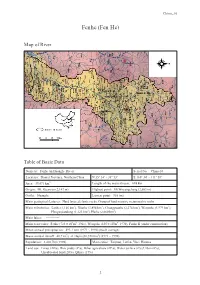

Fenhe (Fen He)

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

Master for Quark6

Special Feature s e v i a t Realisms within Conundrum c n i e h The Personal and Authentic Appeal in Jia Zhangke’s Accented Films (1) p s c r e ESTHER M. K. CHEUNG p With persistent efforts on constructing personal and collective memories arising from the unprecedented transformations in post-socialist China, Jia Zhangke has produced an ensemble of realist films with an impressive personal and authentic appeal. This paper examines how his films are characterised by a variety of accents, images of authenticity, a quotidian ambience, and a new sense of materiality within the local-global nexus. Within a tripartite model of truth, identity, and performance, Jia’s oeuvres demonstrate the powerful performativity of different modes of realism arising out of a state of conundrum when China undergoes a transition from planned economy into wholesale marketisation and globalisation. The appeal of Jia Zhangke’s fined to documentary realism. His films serve to write up a accented cinema history of his generation: rom his first feature Xiao Wu (aka The Pickpocket , I made these films because I wanted to compensate 1997) to 24 City (2008), Jia Zhangke’s films have for what was not fulfilled. I must also emphasise that Fbeen characterised by an impressive personal and au - apart from the realist mode, there are other kinds of thentic appeal. As viewers, in about a decade’s time we have representation that can be called “visual memory”; for observed an ongoing process of the director’s negotiation example, Dali’s surrealist images in the early twentieth with realism as a mode of film representation. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Great Wall Bibliography, Authors

China Heritage Quarterly, No. 6 (June 2006) Great Wall Bibliography (III) © China Heritage Quarterly www.chinaheritagequarterly.org College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Authors L-N Lan Yong 蓝勇, Zhongguo lishi dili xue 中国历史地理学 (Chinese historical geography), Beijing: Gaodeng Jiaoyu Chubanshe 高 等教育出版社, 2002. Li Bingcheng 李并成, 'Han Lingjucheng ji qi fujin Han changcheng yizhi de diaocha yu kaozheng' 汉令居城及其附近汉长 城遗址的调查与考证 (A survey and textual study of the Han dynasty Lingjucheng and the adjacent ruins of the Han dynasty Great Walls), Changcheng xuekan 长城学刊 (Great wall studies), 1991, issue no. 1. Li Bingcheng 李并成, Hexi zoulang lishi dili 河西走廊历史地理 (The historical geography of the Hexi corridor), Lanzhou: Gansu Renmin Chubanshe 甘肃人民出版社, 1995. Li Bingcheng 李并成, 'Hexi zoulang xibu Han changcheng yiji jiqi xiangguan wenti kao' 河西走廊西部汉长城遗迹及其相关问题考 (Sites of the Great Walls of the Han dynasty in the western Hexi corridor and related issues), Dunhuang yanjiu 敦煌研究 (Dunhuang research), 1995:2, pp 135-145. Li Bingcheng 李并成, 'Hexi zoulang dongbu xin faxian de yitiao Han changcheng: Han Xuci xian zhi Aowei xian duan changcheng kaocha' 河西走廊东部新发现的一条汉长城: 汉揟次县至媪围县段长城考察 (The recent discovery of a section of the Han dynasty Great Walls in the eastern part of the Hexi corridor: A survey of the section of wall from Xuci to Aowei counties), Dunhuang yanjiu 敦煌研究 (Dunhuang research), 1996:4, pp 129-131, 112. Li Fangzhun 李方准, 'Changcheng xue yanjiu de yici shenghui: Shoujie changcheng guoji xueshu yantaohui gaishu' 长城学研究 的一次盛会: 首届长城国际学术研讨会概述 (A celebration of research in Great Walls studies: A summary of the 1st international conference of Great Walls studies), Wenshi zhishi 文史知识 (Chinese literature and history), 1995:3, pp 50-57. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 © Copyright by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The How and Why of Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China by Jonathan Stanhope Bell Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Chair China’s urban landscape has changed rapidly since political and economic reforms were first adopted at the end of the 1970s. Redevelopment of historic city centers that characterized this change has been rampant and resulted in the loss of significant historic resources. Despite these losses, substantial historic neighborhoods survive and even thrive with some degree of integrity. This dissertation identifies the multiple social, political, and economic factors that contribute to the protection and preservation of these neighborhoods by examining neighborhoods in the cities of Beijing and Pingyao as case studies. One focus of the study is capturing the perspective of residential communities on the value of their neighborhoods and their capacity and willingness to become involved in preservation decision-making. The findings indicate the presence of a complex interplay of public and private interests overlaid by changing policy and economic limitations that are creating new opportunities for public involvement. Although the Pingyao case study represents a largely intact historic city that is also a World Heritage Site, the local ii focus on tourism has disenfranchised residents in order to focus on the perceived needs of tourists. -

Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia

CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 March 1992 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-059-6 Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch/Asia was established in 1985 to monitor and promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Asia. Sidney Jones is the executive director; Mike Jendrzejczyk is the Washington director; Robin Munro is the Hong Kong director; Therese Caouette, Patricia Gossman and Jeannine Guthrie are research associates; Cathy Yai-Wen Lee and Grace Oboma-Layat are associates; Mickey Spiegel is a research consultant. Jack Greenberg is the chair of the advisory committee and Orville Schell is vice chair. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Helsinki division. Today, it includes five divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, as well as the signatories of the Helsinki accords.