Free Food for Millionaires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE the MIM Music

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The MIM Music Theater Announces Winter/Spring 2020 Concert Series PHOENIX (December 12, 2019) – The MIM Music Theater proudly announces its Winter/Spring 2020 Concert Series, with tickets on sale to the public on December 12 at 10:00 a.m. The new series, running from January through May, includes more than thirty-five concerts spanning multiple genres across the globe. Highlights this season include Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq; Playing for Change, a unique fusion of talents who come together to inspire the world through music; blues vocalist and pianist Marcia Ball with virtuoso slide guitarist and bandleader Sonny Landreth; legendary trumpet player Herb Alpert and Grammy-winning vocalist Lani Hall; and Juan de Marcos, founder of the Buena Vista Social Club, leading the Afro-Cuban All Stars. The Winter/Spring 2020 Concert Series welcomes some artists who will be performing at the MIM Music Theater for the first time. New artists include Americana and folk duo the Secret Sisters; iconic Mexican American singer Lila Downs; pioneer of the minimalist movement, composer, and musician Terry Riley, accompanied by his son Gyan Riley on guitar; and country music hitmaker and piano-pounding powerhouse Phil Vassar. Concertgoers can also look forward to the return of several favorites to the MIM Music Theater, including Grammy-winning bass player Victor Wooten, traditional Irish music group Altan, classical tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain, and Grammy- and Tony-winning jazz giant Dee Dee Bridgewater paying tribute to musical icon Ella Fitzgerald. The MIM Music Theater presents over 290 concerts per year and has had over 150 Grammy- winning artists perform on its stage. -

How a Family Tradition Endures

SOCIETY SOCIETY Left, Min Jin Lee, in blue, and her sisters celebrate the New Year in Seoul, 1976; below, Ms. Lee’s parents, Mi Hwa Lee (left) and Boo Choon Lee, do likewise in New Jersey, 2005. MY KOREAN NEW YEAR How a family tradition endures By Min Jin Lee y finest hour as a Korean took According to Seollal tradition, a Korean has Upon the completion of a bow, we’d receive an practice of observing Jan. 1 as New Year’s Day, place on a Seollal morning, the to eat a bowl of the bone-white soup filled with elder’s blessing and money. A neighborhood when it’s called Shinjeong. Some Koreans still first day of Korean New Year’s, in coin-shaped slices of chewy rice cake in order to bowing tour to honor the elders could yield a do. Consequently the country now observes January 1976. age a year—a ritual far more appreciated early handsome purse. two different national holidays as New Year’s— I was 7 years old, and my in life. The garnishes vary by household; my My cousins and my older sister Myung Jin one on Jan. 1 and the other according to the Mfamily still lived in Seoul, where my two sisters family topped our soup with seasoned finished in a jiffy and collected their rewards. moon. When we moved to the U.S., Jan. 1 and I had been born. Seollal, the New Year’s Day shredded beef, toasted laver (thin sheets of Uncle and Aunt waited for me to bow. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Pachinko by Min Jin

Pachinko Discussion Questions 1. The novel's opening sentence reads, "History has failed us, but no matter." What does the sentence mean, and what expectations might it establish for the reader? Why the tail end of the sentence, "but no matter"? 2. Talk about the thematic significance of the book's title. Pachinko is a sort of slot/pinball game played throughout Japan, and it's arcades are also a way for foreigners to find work and accumulate money. 3. What are the cultural differences between Korea and Japan? 4. As "Zainichi," non-Japanese, how are Koreans treated in Japan? What rules must they adhere to, and what restrictions apply to them? Author: Min Jin Lee 5. Follow-up to Questions 3 and 4: Discuss the theme of belonging, which is Originally published: pervades this novel. How does where one "belongs" tie into self-identity? February 7, 2017 Consider Mozasu and his son, Solomon. In what ways are their experiences Genre: Historical Fiction, Domestic fiction similar when it comes to national identity? How do both of them feel toward the Japanese? 6. How is World War II viewed in this novel—especially from the perspective of the various characters living in Japan? Has reading about the war through their eyes altered your own understanding of the war? 7. How would you describe Sunja and Isak. How do their differing innate talents complement one another and enable them to survive in Japan? 8. Are there particular characters you were drawn to more than others, perhaps even those who are morally compromised? If so who...and why? Author Bio • Birth: 1968, Seoul, South Korea; Raised: Borough of Queens, New York • Education: B.A., Yale University; J.D., Georgetown University • Currently: Lives in New York, NY Min Jin Lee is a Korean-American writer and author, whose work frequently deals with Korean American topics. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Dee Dee Bridgewater

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Dee Dee Bridgewater PERSON Bridgewater, Dee Dee Alternative Names: Dee Dee Bridgewater; Life Dates: May 27, 1950- Place of Birth: Memphis, Tennessee, USA Residence: New Orleans, LA Occupations: Singer; Actress Biographical Note Singer and actress Dee Dee Bridgewater was born on May 27, 1950 in Memphis, Tennessee. Raised in Flint, Michigan, Bridgewater was exposed early to jazz music; her father, Matthew Garrett, was a jazz trumpeter and teacher at Manassas High School. After high school, Bridgewater attended Michigan State University before transferring to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 1969, she toured the Soviet Union with the University of Illinois Big Band. In 1970, Bridgewater met and married trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater and moved to New York City. She sang lead vocals for the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra in the early 1970s, and appeared in the Broadway musical The Wiz from 1974 to 1976. Bridgewater also released her first album in 1974, entitled Afro Blue. Then, after touring France in 1984 with the musical Sophisticated Ladies, she moved to Paris in 1986 and acted in the show Lady Day. Bridgewater also formed her own backup group around this time and performed at the Sanremo Song Festival in Italy and the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1990. Four years later, she collaborated with Horace Silver and released the album Love and Peace: A Tribute to Horace Silver. She then released a tribute album, entitled Dear Ella, in 1997, and the record Live at Yoshi’s in 1998. Subsequent albums included This is New (2002); J'ai Deux Amours (2005); Red Earth (2007); and Eleanora Fagan (1915-1959): To Billie with Love from Dee Dee Bridgewater (2010). -

Dee Dee Bridgewater

B.H. Hopper Management Stievestr. 9 - D-80638 München - Tel. +49 (0)89-177031 - Fax. +49 (0)89-177067 email: [email protected] - http://www.hopper-management.com DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER Biography Today Dee Dee is a sparkling ambassador for jazz, but she bathed in its music before she could walk: her mother played the greatest albums of Ella Fitzgerald for her, and her father was a trumpeter who taught music - to Booker Little, Charles Lloyd and George Coleman, amongst others - and who also played in the summer with Dinah Washington. It's the kind of background that leaves its mark on an adolescent, especially one who appeared solo and with a trio as soon as she was able. Dee Dee's other vocation, that of a globetrotter, reared its head when she toured the Soviet Union, in 1969, with the University of Illinois Big Band. A year later, she followed her then husband, Cecil Bridgewater, to New York. Cecil was playing with pianist Horace Silver, and Dee Dee's dream was to sing Horace's compositions one day... Love and Peace, (Verve), her irresistible 1994 album, was that same dream come true. The young singer made an earth-shattering debut in New York; for four years she was the lead vocalist with the band led by Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, an early career marked by concerts and recordings with such authentic giants as Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, Max Roach, Roland Kirk... and also rich experiences with Norman Connors, Stanley Clarke, and Frank Foster's "Loud Minority". -

Dear Ella (SATB W/Rhythm Section)

SATB Vocal Score Sole Selling Agent for this Arrangement: Jazz Ballad www.MichMusic.com Level II+ Dear Ella (SATB w/rhythm section) MUSIC & LYRICS: Kenny Burrell ARRANGEMENT: Michele Weir Permission to print or perform this arrangement granted only to purchaser of this arrangement. Violators will be prosecuted. SATB Level II+ Dear Ella Recorded by American River College Vocal Jazz Ensemble's CD "Orange Colored Sky" (Art Lapierre, Director) Music & Lyrics: Kenny Burrell Jazz Ballad å=58 Arranged: Michele Weir Sop/Alto P & 4 ‰ ∑ ∑ Ó Œ ‰ j dearœ P Ten/Bass œ ? 4 ‰ ∑ ∑ Ó Œ ‰ J * (See Note Below) 3 3 3 Solo P & Ó Œ ‰ j ‰ Ó ∑ 5 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ ourœ spec-ial first la-dy of song here's to you S/A & ∑ ∑ Ó Œ ‰ j 5 œ œœ œœ ˙ el-la dearœ T/B œ œ œ ? œ œ œ ˙ ∑ ∑ Ó Œ ‰ œ 5 J 3 3 3 Solo Ó Œ ‰ ‰ ∑ 9& j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ w youœ gave us your best for so long yes it's true F S/A ∑ ∑ Ó Œ 9& œ œ œ b˙ el-la dearœ T/B œ œ œ b˙ F œ ? œ œ œ ˙ ∑ ∑ Ó Œ 9 * Solos can be somewhat improvisational, esp. later in the chart. Distribution of solos is at your discretion: a variety of different singers (female or male, 8vb) can be featured, or, one or two only. 3 S/A j & bœ œ œ œ ‰ j œ œœ œ œ ‰ œ j 13 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ b˙ el - la we'reœ all so glad that you ans-wered the call ans-wered the j j j j T/B bœ œ œ œ œ œ #œœ œœ œ œ œ bœ œ ? b œ œ œ œ ‰ nœ œ Œ œ œ œœ ˙ 13 J ansJ -wered theJ call 3 S/A j Œ œ œ œ œ ‰ œ œ œ œ œ ‰ 16& ˙ #œ œ œ #œ œ #œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ #œ a œ n˙ for it's cer - tain that you and your mu - sic b willœ call 3 (Crossed ˙ parts) œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ #œ -

Dossier De Presse

DOSSIER DE PRESSE DIRECTEUR ARTISTIQUE Jean-René PALACIO RELATIONS PRESSE Agnès MARSAN [email protected] T. +377 98 06 64 12 WEB & RÉSEAUX SOCIAUX montecarlosbm.com facebook.com/montecarlojazzfestival twitter.com/montecarlosbm #MCJF 2 3 SOMMAIRE Édito de Jean-René PALACIO p. 5 Programmation p. 6 Exposition photographique de Philip DUCAP p. 19 Partenaires p. 20 L’Opéra : consécration du raffinement et des arts p. 21 Informations p. 23 4 ÉDITO DE JEAN-RENÉ PALACIO Du 25 au 29 novembre 2014, se déroulera la 9ème édition du Monte- Carlo Jazz Festival à la Salle Garnier de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo. La musique de jazz et la musique en général trouvent toute leur place dans ce lieu merveilleux, temple de la musique et de la création depuis plus d’un siècle. Cette nouvelle édition du Monte-Carlo Jazz Festival reflète le jazz d’aujourd’hui, qui s’ouvre vers les musiques du monde et qui donne une large place à la voix. Nous ouvrirons le 25 novembre avec Galliano, Lagrène, Lockwood Trio : accordéon, guitare, violon sont les symboles d’un jazz aux racines européennes. Le même soir, Sylvain Luc & Stefano Di Battista Quartet, une formation exceptionnelle autour de deux solistes de grand talent. Jean-Lou Treboux, jeune vibraphoniste de talent, ouvrira la soirée. Mercredi 26 novembre, Ibrahim Maalouf et Kenny Garrett et leurs différentes formations nous permettront d’aller des couleurs de l’Orient, du rock et du jazz, à la musique afro-américaine. Le 27 novembre est une soirée placée sous le signe des musiques du monde avec Céu tout d’abord, jeune vocaliste brésilienne, puis avec l’Orchestre El Gusto qui est une véritable expérience humaine et musicale avec 20 musiciens sur scène. -

Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Saturday, January 19, 2013, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour 55th Anniversary Celebration Dee Dee Bridgewater vocals Christian McBride bass, musical director Benny Green piano Lewis Nash drums Chris Potter saxophones Ambrose Akinmusire trumpet PROGRAM The program will be announced from the stage. Music will be an assortment of classic jazz repertoire and original compositions by band members. Jazz at Cal Performances is sponsored by Nadine Tang and Bruce Smith. Cal Performances’ 2012–2013 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 5 PROGRAM NOTES ABOUT THE ARTISTS he monterey jazz festival, the lon- bringing leading jazz performers to work with The multitalented, two-time James Brown, Queen Latifah, Carly Simon, Tgest continuously running jazz festival in students throughout the year, includes their ap- Grammy-winning vocalist Sonny Rollins, and Roy Haynes. As a recording the world, has presented nearly every major jazz pearance at the Next Generation Jazz Festival, and Tony Award-winning ac- artist, Mr. McBride has released albums on the star—from Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong Summer Jazz Camp, and the Monterey Jazz tress Dee Dee Bridgewater Verve, Warner Brothers, and Mack Avenue la- to Esperanza Spalding and Trombone Shorty— Festival, both in performance and instruction. has had an illustrious career. bels, including the critically acclaimed Kind of since it was founded in 1958. World-renowned A leader in jazz education, the Festival Since her New York debut Brown (2009), recorded with his group Inside for its artistic excellence, sophisticated infor- has also presented the winning bands from its in 1970, she has appeared Straight, and the Grammy-winning The Good mality, and longstanding mission to create and high school competition since 1971, and has with the Thad Jones/Mel Feeling (2011), his first big-band recording as a support year-round jazz education and perfor- showcased talented young musicians in an Lewis Orchestra, Sonny leader, arranger, and conductor. -

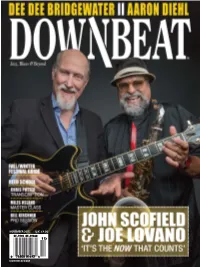

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk;