Smokefree Regional Survey Report September 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Witness List

List of Witnesses Part One Ronald Henry Abdinor Marketing and Personnel Manager Tai Poutini Polytechnic Graeme John Alexander Building Inspector Buller District Council Terence Neale Archer Manager, Regulatory Services Buller District Council John Stafford Bainbridge Senior Conservation Officer Department of Conservation Rodney George Chambers Development Officer, Coast Care Programme Christchurch City Council Calvin Fraser Cochrane Regional Works Officer Department of Conservation Ian Ross Davidson Finance Officer Department of Conservation Mark Peter Davis Conservancy Mining Officer Department of Conservation Dr Alan Spencer Edmonds Deputy Director General Department of Conservation Kevin James Field Conservation Officer Department of Conservation Lakshman Ravindra Fernando Planning Officer Buller District Council Darren William Gamble Student (Survivor) Tai Poutini Polytechnic William Stuart Gilbertson Chairperson Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society, West Coast Kathryn Helen Groome Senior Conservation Officer, Recreation/Tourism Liaison Department of Conservation Bruce Neville Hamilton Chairperson West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board Wayne Douglas Harper Worker Department of Conservation Annabelle Hasselman Recreation Design Planner Department of Conservation Alan Brent Hendrickson Constable New Zealand Police Keith Norman Johnston Executive Manager, Strategic Development Department of Conservation William Ramsay Mansfield Director General of Conservation Ian Scott McClure Human Resources and Administration Manager Department -

Notes Subscription Agreement)

Amendment and Restatement Deed (Notes Subscription Agreement) PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited Issuer The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 Subscribers 3815658 v5 DEED dated 2020 PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited ("Issuer") The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 ("Subscribers" and each a "Subscriber") INTRODUCTION The parties wish to amend and restate the Notes Subscription Agreement as set out in this deed. COVENANTS 1. INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions: In this deed: "Notes Subscription Agreement" means the notes subscription agreement dated 7 December 2011 (as amended and restated on 4 June 2015) between the Issuer and the Subscribers. "Effective Date" means the date notified by the Issuer as the Effective Date in accordance with clause 2.1. 1.2 Notes Subscription Agreement definitions: Words and expressions defined in the Notes Subscription Agreement (as amended by this deed) have, except to the extent the context requires otherwise, the same meaning in this deed. 1.3 Miscellaneous: (a) Headings are inserted for convenience only and do not affect interpretation of this deed. (b) References to a person include that person's successors, permitted assigns, executors and administrators (as applicable). (c) Unless the context otherwise requires, the singular includes the plural and vice versa and words denoting individuals include other persons and vice versa. (d) A reference to any legislation includes any statutory regulations, rules, orders or instruments made or issued pursuant to that legislation and any amendment to, re- enactment of, or replacement of, that legislation. (e) A reference to any document includes reference to that document as amended, modified, novated, supplemented, varied or replaced from time to time. -

Maritime Contacts

HARBOURMASTERS Port/Region Address and Email Telephone Mobile AUCKLAND Auckland Transport +64 9 362 0397 Private Bag 92250, Auckland 1142 [email protected] Emergency 24 hour Duty Officer + 64 9 362 0397 ext 1 CHATHAM ISLANDS PO Box 24, Chatham Islands 8942 +64 3 305 0033 [email protected] GISBORNE Gisborne District Council 0800 653 800 027 610 3100 PO Box 747, Gisborne 4040 +64 6 867 2049 [email protected] GREYMOUTH Port of Greymouth +64 3 768 5666 33 Lord St, Greymouth 7805 PO Box 382, Greymouth 7840 [email protected] LYTTELTON, Environment Canterbury +64 3 353 9007 TIMARU, AKAROA - PO Box 345, Christchurch 8140 AND KAIKOURA [email protected] 0800 324 636 NAPIER Hawke’s Bay Regional Council +64 6 833 4525 027 445 5592 Private Bag 6006, Napier 4142 [email protected] NELSON Port Nelson, 8 Vickerman Street, Port Nelson +64 3 548 2099 021 072 4667 PO Box 844, Nelson 7040 +64 3 546 9015 [email protected] NORTHLAND Regional Harbourmaster +64 9 470 1200 36 Water Street, Whanga-rei 0110 [email protected] Emergency and 24 hour Duty Officer 0800 504 639 OTAGO Otago Regional Council +64 3 474 0827 027 583 5196 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 027 587 7708 Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 [email protected] PICTON AND Marlborough District Council +64 3 520 7400 MARLBOROUGH Picton Customer Service Centre 67 High Street, Picton 7220 [email protected] QUEENSTOWN Harbourmasters Office +64 3 442 3445 027 434 5289 AND WANAKA Frankton Marina Queenstown 027 414 2270 PO Box 108, Arrowtown 9351 [email protected] SOUTHLAND Environment Southland +64 3 211 5115 021 673 043 Cnr. -

Buller District Council

Buller District Council Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act compliance and practice The Ombudsman | Kaitiaki Mana Tangata Feb 2021 LGOIMA compliance and practice in Buller District Council The Ombudsman | Kaitiaki Mana Tangata February 2021 ISBN: 978-0-473-56379-0 Cover image: Oparara Arches, Karamea (credit Nimmo Gallery) Office of the Ombudsman | Tari o te Kaitiaki Mana Tangata LGOIMA compliance and practice at Buller District Council Opinion of the Chief Ombudsman September 2020 Contents Foreword ______________________________________________________________ 4 Introduction ___________________________________________________________ 6 Buller District Council: a snapshot __________________________________________ 9 Executive summary _____________________________________________________ 10 Lifting LGOIMA performance at Buller District Council: summary of actions ________ 16 Leadership and culture __________________________________________________ 17 Organisation structure, staffing, and capability _______________________________ 25 Internal policies, procedures and resources _________________________________ 31 Current practices ______________________________________________________ 42 Performance monitoring and learning ______________________________________ 52 Appendix 1. Official information practice investigation — terms of reference _______ 58 Appendix 2. Key dimensions and indicators __________________________________ 64 Appendix 3. ‘Timeline and methodology’ diagram verbalisations _________________ 79 Appendix -

Waste Disposal Facilities

Waste Disposal Facilities S Russell Landfill ' 0 Ahipara Landfill ° Far North District Council 5 3 Far North District Council Claris Landfill - Auckland City Council Redvale Landfill Waste Management New Zealand Limited Whitford Landfill - Waste Disposal Services Tirohia Landfill - HG Leach & Co. Limited Hampton Downs Landfill - EnviroWaste Services Ltd Waiapu Landfill Gisborne District Council Tokoroa Landfill Burma Road Landfill South Waikato District Council Whakatane District Council Waitomo District Landfill Rotorua District Sanitary Landfill Waitomo District Council Rotorua District Council Broadlands Road Landfill Taupo District Council Colson Road Landfill New Plymouth District Council Ruapehu District Landfill Ruapehu District Council New Zealand Wairoa - Wairoa District Council Waiouru Landfill - New Zealand Defence Force Chatham Omarunui Landfill Hastings District Council Islands Bonny Glenn Midwest Disposal Limited Central Hawke's Bay District Landfill S ' Central Hawke's Bay District Council 0 ° 0 4 Levin Landfill Pongaroa Landfill Seafloor data provided by NIWA Horowhenua District Council Tararua District Council Eves Valley Landfill Tasman District Council Spicer Valley Eketahuna Landfill Porirua City Council Silverstream Landfill Tararua District Council Karamea Refuse Tip Hutt City Council Buller District Council Wainuiomata Landfill - Hutt City Council Southern Landfill - Wellington City Council York Valley Landfill Marlborough Regional Landfill (Bluegums) Nelson City Council Marlborough District Council Maruia / Springs -

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service (Compilers) Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2006 © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2006 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without limitation, provided Landcare Research New Zealand Limited is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of Landcare Research New Zealand Limited. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Spurr, E.B. Development of bird population monitoring in New Zealand: proceedings of a workshop / Eric B. Spurr and C. John Ralph, compilers – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, 2006. (Landcare Research Science series, ISSN 1172-269X; no. 32) ISBN-13: 978-0-478-09384-1 ISBN-10: 0-478-09384-5 1. Bird populations – New Zealand. 2. Birds – Monitoring – New Zealand. 3. Birds – Counting – New Zealand. I. Spurr, E.B. II. Series. UDC 598.2(931):574.3.087.001.42 Edited by Christine Bezar Layout design Typesetting by Wendy Weller Cover design by Anouk Wanrooy Published by Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, PO Box 40, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand. 3 Contents Summary ..............................................................................................................................4 -

South Island Infrastructure Investment

South Island Infrastructure Investment • Rolling out more than $7 billion of investment in transport projects, schools, hospitals and water infrastructure across the South Island. • Commitment to rolling our shovel-ready projects and a pipeline of long-term projects to create certainty for our construction sector. Labour will continue to build on its strong record of investment in infrastructure and roll out more than $7 billion of infrastructure investment in the South Island. Our $7 billion of infrastructure investment in the South Island provides certainty to the regions and employers. This investment will result in long-term job creation and significant economic benefits. In government, we have managed the books wisely. With historically low interest rates, we are able to outline this much-needed investment in infrastructure. This investment is both affordable and the right thing to do. This will not be all of our infrastructure investment in the next term, and we will continue to invest in capital infrastructure for health, housing, transport and local government, as well as other areas. But this provides a pipeline of work that will assist us in recovering from the impacts of COVID-19. The overall infrastructure investment for the South Island includes: • $274.1 million of investment via the New Zealand Upgrade programme for transport projects • $368.72 million from the Provincial Growth Fund • $667 million from the IRG projects • $3.5 billion from the National Land Transport Programme (forecast 2018-2021). • $6 million from the -

CB List by Zone and Council

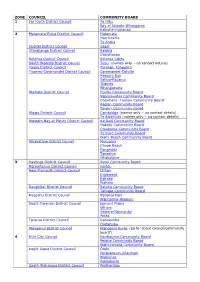

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board -

Te Tai O Poutini Plan Committee Meeting to Be Held in the Council

Te Tai o Poutini Plan Committee Meeting To be held in the Council Chambers, West Coast Regional Council Thursday 30 July 2020, 10.30am-2.00pm AGENDA 10.30 Welcome and Apologies Chair 10.32 Confirm previous minutes Chair 10.35 Matters arising from previous meeting Chair 10.40 Deed of Agreement and Conflicts of Interest Chair Register 10.45 Technical Update – Ecosystems and Indigenous Principal Planner Biodiversity 11.15 Technical Update – Transport Issues, objectives Senior Planner and Policies 12.00 Lunch 12.25 Technical Update – Rural Areas and Principal Planner Settlements - Issues and Objectives 1.10 Technical Update – Plan Change Process Principal Planner 1.40 Paper – Approach to Consultation Project Manager 1.50 General Business Chair 2.00 Meeting Ends Meeting Dates for 2020 Thursday 25 August (Arahura Marae) Thursday 24 September (Buller District Council) Thursday 29 October (Grey District Council) Tuesday 26 November (West Coast Regional Council) Wednesday 14 December (Westland District Council) THE WEST COAST REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES OF MEETING OF TE TAI O POUTINI PLAN COMMITTEE HELD ON 24 JUNE 2020, VIA ZOOM, (DUE TO COVID – 19) COMMENCING AT 09.00 A.M. PRESENT: R. Williams (Chairman), A. Birchfield, M. Montgomery, S. Roche, T. Gibson, B. Smith, A. Becker, L. Coll McLaughlin, P. Madgwick, L. Martin, F Tumahai (left meeting at 10.00am). IN ATTENDANCE: J. Armstrong (Project Manager), L. Easton, E. Bretherton, M. Meehan (WCRC), S. Bastion (WDC), P. Morris, (GDC) WELCOME The Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting. He advised that WCRC is hosting the meeting via Zoom. He reminded those present that this is a public meeting and members of the public as well as media are welcome to attend. -

ALGIM Member Subscription Service List of Council’S/CCO’S Webinar Subscription Level Pricing Structure

Published June 2021 ALGIM Member Subscription Service List of Council’s/CCO’s webinar subscription level pricing structure NB. Per annual subscription year of 12 months, a minimum of 24 webinars will be included in the subscription fee. If a Council/CCO does not choose to join the subscription service then the following costs will apply per webinar: $125 individual, $300 Whole Council/CCO (excl. GST) Council ALGIM Webinar Annual Subscription Fee Subscription Level 1 Jul 2021 – 30 Jun 2022 (excl. GST) Auckland Council Christchurch City Council 3 $2,285.00 Dunedin City Council Environment Canterbury Greater Wellington Hamilton City Council Hastings District Council Hutt City Council New Plymouth District Council Palmerston North City Council Rotorua Lakes Council Tauranga City Council Waikato Regional Council Waikato District Council Wellington City Council Whangarei District Council Ashburton District Council Bay of Plenty Regional Council 2 $1780.00 Far North District Council Gisborne District Council Great Lake Taupo District Council Horizons Regional Council Horowhenua District Council Invercargill City Council Kapiti Coast District Council Napier City Council Nelson City Council Manawatu District Council Marlborough District Council Matamata Piako District Council Porirua City Council Queenstown Lakes District Council Selwyn District Council South Taranaki District Council Southland District Council Tasman District Council Thames Coromandel District Council Timaru District Council Upper Hutt City Council Waimakariri District Council -

Advisory Committee Papers for 23 March 2018 Meeting

ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING 23 March 2018 10.30am St John Water Walk Road, Greymouth AGENDA AND MEETING PAPERS ALL INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THESE COMMITTEE PAPERS IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE COMMITTEE MEMBERS WEST COAST DISTRICT HEALTH BOARD ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS Elinor Stratford (Joint Chair) Michelle Lomax (Joint Chair) Chris Auchinvole Jenny Black Lynnette Beirne Kevin Brown Sarah Birchfield Cheryl Brunton Paula Cutbush Helen Gillespie Chris Lim Jenny McGill Chris Mackenzie Joseph Mason Eddie Moke Mary Molloy Peter Neame Nigel Ogilvie Francois Tumahai EXECUTIVE SUPPORT David Meates (Chief Executive) Karyn Bousfield (Director of Nursing) Gary Coghlan (General Manager, Maori Health) Mr Pradu Dayaram (Medical Director, Facilities Development) Michael Frampton (General Manager, People & Capability) Carolyn Gullery (General Manager, Planning & Funding) Dr Cameron Lacey (Medical Director, Medical Council, Legislative Compliance and National Representation) Dr Vicki Robertson (Medical Director, Patient Safety and Outcomes) Karalyn van Deursen (Strategic Communications Manager) Stella Ward (Executive Director, Allied Health) Philip Wheble (General Manager, West Coast) Justine White (General Manager, Finance) Kay Jenkins (Board Secretary) Membership-AdvisoryCommittee-23March2018 Page 1 of 1 23 March 2018 AGENDA WEST COAST ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING To be held at St John, Water Walk Road Greymouth Friday 23 March commencing at 10.30am ADMINISTRATION 10.30am Karakia Welcome by Board Chair Apologies 1. Interest Register Update Committee Interest Register and Declaration of Interest on items to be covered during the meeting. 2. Minutes of the Previous Meetings • Hospital Advisory Committee – 23 November 2017 • Community & Public Health & Disability Support Advisory Committee – 23 November 2017 • Carried Forward Items/Action Points 3. Patient Story REPORTS/PRESENTATIONS 10.40am 4. -

Harbourmasters

HARBOURMASTERS Port/Region Address and Email Telephone Facsimile Mobile AUCKLAND Auckland Transport +64 9 362 0397 Private Bag 92250, Auckland 1142 [email protected] Emergency 24 hour Duty Officer + 64 9 362 0397 ext 1 CHATHAM ISLANDS PO Box 24, Chatham Islands 8942 +64 3 305 0033 [email protected] GISBORNE Gisborne District Council 0800 653 800 027 610 3100 PO Box 747, Gisborne 4040 +64 6 867 2049 [email protected] GREYMOUTH Port of Greymouth +64 3 768 5666 33 Lord St, Greymouth 7805 PO Box 382, Greymouth 7840 [email protected] LYTTELTON, Environment Canterbury +64 3 353 9007 TIMARU, AKAROA Level 1, 5 Norwich Quay, Lyttelton 8082 AND KAIKOURA PO Box 345, Christchurch 8140 0800 324 636 [email protected] NAPIER Hawke’s Bay Regional Council +64 6 833 4525 027 445 5592 Private Bag 6006, Napier 4142 [email protected] NELSON Port Nelson, 8 Vickerman Street, Port Nelson +64 3 548 2099 021 072 4667 PO Box 844, Nelson 7040 +64 3 546 9015 [email protected] NORTHLAND Regional Harbourmaster +64 9 470 1200 +64 9 470 1202 36 Water Street, Whangarei 0110 [email protected] Emergency and 24 hour Duty Officer 0800 504 639 OTAGO Otago Regional Council +64 3 474 0827 +64 3 479 0015 027 583 5196 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 027 587 7708 Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 [email protected] PICTON AND Marlborough District Council +64 3 520 7400 MARLBOROUGH Picton Customer Service Centre 67 High Street, Picton 7220 [email protected] QUEENSTOWN Harbourmasters Office +64 3 442 3445 027 434 5289 AND WANAKA Frankton Marina Queenstown 027 414 2270 PO Box 108, Arrowtown 9351 [email protected] SOUTHLAND Environment Southland +64 3 211 5115 +64 3 211 5252 021 673 043 Cnr.