The Blind Man's Elephant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Management Models in Africa

Collaborative Management Models in Africa Peter Lindsey Mujon Baghai Introduction to the context behind the development of and rationale for CMPs in Africa Africa’s PAs represent potentially priceless assets due to the environmental services they provide and for their potential economic value via tourism However, the resources allocated for management of PAs are far below what is needed in most countries to unlock their potential A study in progress indicates that of 22 countries assessed, half have average PA management budgets of <10% of what is needed for effective management (Lindsey et al. in prep) This means that many countries will lose their wildlife assets before ever really being able to benefit from them So why is there such under-investment? Two big reasons - a) competing needs and overall budget shortages; b) a high burden of PAs relative to wealth However, in some cases underinvestment may be due to: ● Misconceptions that PAs can pay for themselves on a park level ● Lack of appreciation among policy makers that PAs need investment to yield economic dividends This mistake has grave consequences… This means that in most countries, PA networks are not close to delivering their potential: • Economic value • Social value • Ecological value Africa’s PAs are under growing pressure from an array of threats Ed Sayer ProtectedInsights areas fromare becoming recent rapidly research depleted in many areas There is a case for elevated support for Africa’s PA network from African governments But also a case for greater investment from -

2019 LRF Progress Report

February 2019 Progress Report LION RECOVERY FUND ©Frans Lanting/lanting.com Roaring Forward SINCE AUGUST 2018: $1.58 Million granted CLAWS Conservancy, Conservation Lower Zambezi, Honeyguide, Ian Games (independent consultant), Kenya Wildlife Trust, Lilongwe Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC frica’s lion population has declined by approximately half South Africa, WildAid, Zambezi Society, Zambian Carnivore Programme/Conservation South Luangwa A during the last 25 years. The Lion Recovery Fund (LRF) was created to support the best efforts to stop this decline 4 New countries covered by LRF grants and recover the lions we have lost. The LRF—an initiative of Botswana, Chad, Gabon, Kenya the Wildlife Conservation Network in partnership with the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation—entered its second year with a strategic vision to bolster and expand lion conservation LRF IMPACT TO DATE: across the continent. 42 Projects Though the situation varies from country to country, in a number of regions we are starting to see signs of hope, thanks 18 Countries to the impressive conservation work of our partners in the 29 Partners field. Whether larger organizations or ambitious individuals, our partners are addressing threats facing lions throughout $4 Million deployed Africa. This report presents the progress they made from August 2018 through January 2019. 23% of Africa’s lion range covered by LRF grantees Lions can recover. 30% of Africa’s lion population covered There is strong political will for conservation in Africa. Many by LRF grantees African governments are making conservation a priority 20,212 Snares removed and there are already vast areas of land set aside for wildlife throughout the continent. -

Conservation and Management Strategy for the Elephant in Kenya 2012-2021

Conservation and Management Strategy for the Elephant in Kenya 2012-2021 Compiled by: Moses Litoroh, Patrick Omondi, Richard Kock and Rajan Amin Plate 4. Winds 2 Family crossing the Ewaso Ng’iro River, Samburu National Reserve - Lucy King, Save the Elephants ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, we thank the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) Director, Julius Kipng’etich and KWS Board of Trustees for approving this as a priority activity amongst the core business of KWS. Conservation and We also sincerely thank Keith Lindsay, Winnie Kiiru and Noah Sitati for preparing Management Strategy the background information and facilitating the eleven consultative for the Elephant stakeholder-workshops that were held across the country. This ensured the in Kenya views of as many stakeholders as possible were accommodated into this strategy document. Special thanks to all the stakeholders of the final strategy 2012-2021 development workshop, held at Mpala Research Centre, Nanyuki, which © Kenya Wildlife Service included representatives from United Republic of Tanzania; Uganda Government and the Government of Southern Sudan that finally formulated this National Elephant Management and Conservation Strategy. Our sincere gratitude also to the following individuals for reviewing the first draft : Munira Anyonge Bashir, Julian Blanc, Holly Dublin, Francis Gakuya, Ian Douglas-Hamilton, Ben Kavu, Juliet King, Lucy King, Margaret Kinnaird, Ben Okita, Lamin Seboko, Noah Sitati, Diane Skinner, Richard Vigne and David Western. Frontcover: We are greatly indebted to the following institutions for funding the formulation of this strategy : Born Free Foundation; CITES MIKE Programme; Darwin Initiative Plate 1. African Elephant. Samantha Roberts, Zoological / CETRAD; KWS; People’s Trust for Endangered Species; Tusk Trust; United States Society of London Fish and Wildlife Service; World Wildlife Fund (EARPO) and Zoological Society of London (ZSL). -

African Parks 2 African Parks

African Parks 2 African Parks African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the total responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities. By adopting a business approach to conservation, supported by donor funding, we aim to rehabilitate each park making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable in the long-term. Founded in 2000, African Parks currently has 15 parks under management in nine countries – Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia. More than 10.5 million hectares are under our protection. We also maintain a strong focus on economic development and poverty alleviation in neighbouring communities, ensuring that they benefit from the park’s existence. Our goal is to manage 20 parks by 2020, and because of the geographic spread and representation of different ecosystems, this will be the largest and the most ecologically diverse portfolio of parks under management by any one organisation across Africa. Black lechwe in Bangweulu Wetlands in Zambia © Lorenz Fischer The Challenge The world’s wild and functioning ecosystems are fundamental to the survival of both people and wildlife. We are in the midst of a global conservation crisis resulting in the catastrophic loss of wildlife and wild places. Protected areas are facing a critical period where the number of well-managed parks is fast declining, and many are simply ‘paper parks’ – they exist on maps but in reality have disappeared. The driving forces of this conservation crisis is the human demand for: 1. -

Tcd Str Hno2017 Fr 20161216.Pdf

APERÇU DES 2017 BESOINS HUMANITAIRES PERSONNES DANS LE BESOIN 4,7M NOV 2016 TCHAD OCHA/Naomi Frerotte Ce document est élaboré au nom de l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays et de ses partenaires. Ce document présente la vision des crises partagée par l'Equipe Humanitaire Pays, y compris les besoins humanitaires les plus pressants et le nombre estimé de personnes ayant besoin d'assistance. Il constitue une base factuelle consolidée et contribue à informer la planification stratégique conjointe de réponse. Les appellations employées dans le rapport et la présentation des différents supports n'impliquent pas d'opinion quelconque de la part du Secrétariat de l'Organisation des Nations Unies concernant le statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni de la délimitation de ses frontières ou limites géographiques. www.unocha.org/tchad www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/chad @OCHAChad PARTIE I : PARTIE I : RÉSUMÉ Besoins humanitaires et chiffres clés Impact de la crise Personnes dans le besoin Sévérité des besoins 03 PERSONNESPARTIE DANS LEI : BESOIN Personnes dans le besoin par Sites et Camps de déplacement catégorie (en milliers) M Site de retournés 4,7 Population Camp de réfugiés Ressortissants locale de pays tiers Sites/lieux de déplacement interne EGYPTE Personnes xx déplacées Réfugiés MAS supérieur à 2% internes Retournés Phases du Cadre Harmonisé (période projetée, juin-août 2017) LIBYE Minimale (phase 1) Sous pression (phase 2) Crise (phase 3) TIBESTI 13 NIGER ENNEDI OUEST 35 ENNEDI EST BORKOU 82 04 -

SES Scientific Explorer Annual Review 2020.Pdf

SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER Dr Jane Goodall, Annual Review 2020 SES Lifetime Achievement 2020 (photo by Vincent Calmel) Welcome Scientific Exploration Society (SES) is a UK-based charity (No 267410) that was founded in 1969 by Colonel John Blashford-Snell and colleagues. It is the longest-running scientific exploration organisation in the world. Each year through its Explorer Awards programme, SES provides grants to individuals leading scientific expeditions that focus on discovery, research, and conservation in remote parts of the world, offering knowledge, education, and community aid. Members and friends enjoy charity events and regular Explorer Talks, and are also given opportunities to join exciting scientific expeditions. SES has an excellent Honorary Advisory Board consisting of famous explorers and naturalists including Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Dr Jane Goodall, Rosie Stancer, Pen Hadow, Bear Grylls, Mark Beaumont, Tim Peake, Steve Backshall, Vanessa O’Brien, and Levison Wood. Without its support, and that of its generous benefactors, members, trustees, volunteers, and part-time staff, SES would not achieve all that it does. DISCOVER RESEARCH CONSERVE Contents 2 Diary 2021 19 Vanessa O’Brien – Challenger Deep 4 Message from the Chairman 20 Books, Books, Books 5 Flying the Flag 22 News from our Community 6 Explorer Award Winners 2020 25 Support SES 8 Honorary Award Winners 2020 26 Obituaries 9 ‘Oscars of Exploration’ 2020 30 Medicine Chest Presentation Evening LIVE broadcast 32 Accounts and Notice of 2021 AGM 10 News from our Explorers 33 Charity Information 16 Top Tips from our Explorers “I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward.” Mark Beaumont, SES Lifetime Achievement 2018 and David Livingstone SES Honorary Advisory Board member (photo by Ben Walton) SCIENTIFIC EXPLORER > 2020 Magazine 1 Please visit SES on EVENTBRITE for full details and tickets to ALL our events. -

Waging a War to Save Biodiversity: the Rise of Militarized Conservation

Waging a war to save biodiversity: the rise of militarized conservation ROSALEEN DUFFY* Conserving biodiversity is a central environmental concern, and conservationists increasingly talk in terms of a ‘war’ to save species. International campaigns present a specific image: that parks agencies and conservation NGOs are engaged in a continual battle to protect wildlife from armies of highly organized criminal poach- ers who are financially motivated. The war to save biodiversity is presented as a legitimate war to save critically endangered species such as rhinos, tigers, gorillas and elephants. This is a significant shift in approach since the late 1990s, when community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) and participatory techniques were at their peak. Since the early 2000s there has been a re-evaluation of a renewed interest in fortress conservation models to protect wildlife, including by military means.1 Yet, as Lunstrum notes, there is a dearth of research on ‘green militarization’, a process by which military approaches and values are increasingly embedded in conservation practice.2 This article examines the dangers of a ‘war for biodiversity’: notably that it is used to justify highly repressive and coercive policies.3 Militarized forms of anti- poaching are increasingly justified by conservation NGOs keen to protect wildlife; these issues are even more important as conservationists turn to private military companies to guard and enforce protected areas. This article first examines concep- tual debates around the war for biodiversity; second, it offers an analysis of current trends in militarized forms of anti-poaching; third, it offers a critical reflection on such approaches via an examination of the historical, economic, social and political creation of poaching as a mode of illegal behaviour; and finally, it traces how a militarized approach to anti-poaching developed out of the production of poaching as a category. -

TCHAD Province Du Salamat Octobre 2019

TCHAD Province du Salamat Octobre 2019 18°30'0"E 19°0'0"E 19°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 20°30'0"E 21°0'0"E 21°30'0"E 22°0'0"E Dadouar G GAm Bourougne Bang-Bang G Bagoua GKofilo G Dogdore GZarli G Golonti ABTOUYOUR G N Mogororo N " " 0 Koukou G 0 ' G Koukou-Angarana ' 0 G G 0 ° ABTOUYOUR Koukou angara ° 2 G 2 1 Niergui Badago G Goz Amir Tioro 1 G Louboutigue G GAbgué GUÉRA GTounkoul MANGALMÉ KerfGi MANGALMÉ Kerfi GUÉRA GIdbo GBandikao GAl Ardel Localités GFoulounga GMouraye Capitale N ABOUDÉIA N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 Chef-Lieu de province 3 3 ° ° 1 1 1 1 Chef-Lieu de département G Aboudéïa GAm-Habilé GAgrab Dourdoura G Chef-Lieu de sous-préfecture GArdo Camp de réfugiés GDarasna Daradir G Site de déplacés/retournés GMirer Village hôte GZarzoura Amdjabir G Infrastructures GLiwi G Centre de santé/Hopital GIdater Aérodrome Piste d'atterrissage Am Karouma G Am-Timan G Route principale N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 G Am Senene 0 ° Goz Djerat ° 1 G 1 Route secondaire 1 1 Piste Zakouma Limites administratives Aoukalé Frontière nationale S A L A M A T Limite de province Limite de département BARH-SIGNAKA Hydrographie GDaguela BARH-SIGNAKA Plan d'eau BAHR-AZOUM Département Chinguil G GKieke N Zane N " G " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° GUERA ° 0 0 1 Djouna 1 G GMangueïgne HARAZE-MANGUEIGNE Takalaw GBoum-Kebir G LIBYE Tibesti NIGER N N " " 0 0 ' ' Ennedi Ouest 0 0 ° Kia Ndopto ° 0 Male G 0 1 1 Ennedi Est G Haraze Borkou Massidi-Dongo Moyo Kanem Singako Wadi Fira Alako Barh-El-Gazel Batha SOUDAN G LAC IRO Lac Baltoubaye Ouaddaï G R É P U B L I Q U E C E N T R A F R I C A I N E Hadjer-Lamis -

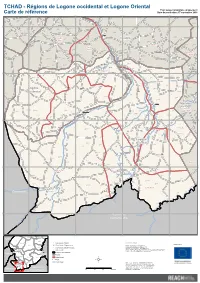

Régions De Logone Occidental Et Logone Oriental

TCHAD - Régions de Logone occidental et Logone Oriental Pour usage humanitaire uniquement Carte de référence Date de production: 07 septembre 2018 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E Gounou Koré Marba Kakrao Ambasglao Boudourr Oroungou Gounaye Djouman Goubou Gabrigué Tagal I Drai Mala Djoumane Disou Kom Tombouo Landou Marba Gogor Birem Dikna Goundo Nongom Goumga Zaba I Sadiki Ninga Pari N N " Baktchoro Narégé " 0 0 ' Pian Bordo ' 0 0 3 Bérem Domo Doumba 3 ° ° 9 Brem 9 Tchiré Gogor Toguior Horey Almi Zabba Djéra Kolobaye Kouma Tchindaï Poum Mbassa Kahouina Mogoy Gadigui Lassé Fégué Kidjagué Kabbia Gounougalé Bagaye Bourmaye Dougssigui Gounou Ndolo Aguia Tchilang Kouroumla Kombou Nergué Kolon Laï Batouba Monogoy Darbé Bélé Zamré Dongor Djouni Koubno Bémaye Koli Banga Ngété Tandjile Goun Nanguéré Tandjilé Dimedou Gélgou Bongor Madbo Ouest Nangom Dar Gandil Dogou Dogo Damdou Ngolo Tchapadjigué Semaïndi Layane Béré Delim Kélo Dombala Tchoua Doromo Pont-Carol Dar Manga Beyssoa Manaï I Baguidja Bormane Koussaki Berdé Tandjilé Est Guidari Tandjilé Guessa Birboti Tchagra Moussoum Gabri Ngolo Kabladé Kasélem Centre Koukwala Toki Béro Manga Barmin Marbelem Koumabodan Ter Kokro Mouroum Dono-Manga Dono Manga Nantissa Touloum Kalité Bayam Kaga Palpaye Mandoul Dalé Langué Delbian Oriental Tchagra Belimdi Kariadeboum Dilati Lao Nongara Manga Dongo Bitikim Kangnéra Tchaouen Bédélé Kakerti Kordo Nangasou Bir Madang Kemkono Moni Bébala I Malaré Bologo Bélé Koro Garmaoa Alala Bissigri Dotomadi Karangoye Dadjilé Saar-Gogne Bala Kaye Mossoum Ngambo Mossoum -

Preserving the African Elephant for Future Generations

OCCASIONAL PAPER 219 Governance of Africa's Resources Programme July 2015 Preserving the African Elephant for Future Generations s ir a f f Ross Harvey A l a n o ti a rn e nt f I o te tu sti n In ica . h Afr ts Sout igh l Ins loba African Perspectives. G ABOUT SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs, with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s occasional papers present topical, incisive analyses, offering a variety of perspectives on key policy issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. ABOUT THE GOVERNA NCE OF AFRI C A ’ S R E S OURCES PROGRA MME The Governance of Africa’s Resources Programme (GARP) of the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) is funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The programme contributes to policy governing the exploitation and extraction of Africa’s natural resources by assessing existing governance regimes and suggesting alternatives to targeted stakeholders. -

SALAMAT TANDJILE CHARI BAGUIRMI GUERA LOGONE ORIENTAL MANDOUL MOYEN CHARI CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Legend

TCHAD:REGION DU MOYEN-CHARI Juin 2010 E E E E " " " " 0 0 0 0 ' ' ' ' 0 0 0 0 ° ° ° ° 7 8 9 0 1 1 1 2 Seaba BAGUIRMI Chinguil Kiéké Matègn Maïra Al Bidia Chinguil Baranga Zan Ndaba Cisi Madi Balo Djomal Ségué Badi Biéré Am Kiféou Chérif Boubour Bankéri Djouna Djouna Mogo Bao Gouri Djember Gadang-gougouri Barao Tiolé Kadji Barlet Gofena Boumbouri Bilabou Karo Al Fatchotchoy Al Oubana Aya Hour Bala Tieau Djoumboul Timan Méré Banker GUE R A Djogo Goudak Aya I BARH BAHR Lagouay SIGNAKA Djimèz Am Biringuel LOUG CHARI Gamboul Djadja Al Itéin AZOUM Miltou Kourmal Tor CHA R I B A GU I RM I Gangli Komo Djigel Karou Siho Tiguili Boum Dassik Gou Tilé Kagni Kabir Takalaou Bibièn Nougar Bobèch Boum Kabir Baranga Lagoye Moufo Al Frèch Kébir Bir El Tigidji Souka Rhala Kané Damraou Délou Djiour Tari Gour Kofé Bouni Djindi Gouaï Béménon Dogoumbo Sarabara Tim Ataway Bakasao Nargon Damtar N N " Korbol " 0 Bar 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 Korbol Malé Dobo Dipkir 0 1 Kalmouna Sali 1 Lour Dik Guer Malbom Sakré Bouane Kouin BAHR KOH Délèb Migna Tousa Dongo Direk Wok Guéléhé SALAMAT Guélé Kalbani Singako Kwaloum Kagnel Tchadjaragué Moula Kouno Gourou Niou Balétoundou Singako Koniène Alako Biobé Kindja Ndam Baltoubay Alako Yemdigué Ndam Kalan Bahitra Baltoubaye Balé Dène Balékolo Balékoutou Niellim Ala Danganjin Kidjokadi Gaogou Mirem Ngina Pongouo Tchigak Moul Boari Kokinio Koubatiembi Roukou TANDJILE EST Palik Bébolo Roro Koubounda Gori Koulima Korakadja Simé Djindjibo Bari Kaguessem Gotobé Balé Dindjebo Gounaye Tolkaba Gilako Béoulou Yanga Ladon Mandjoua Gabrigué Hol Bembé -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Chad

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CHAD Original Map Courtesy of the UN Cartographic Section 15° 20° 25° The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. EGYPT CHAD LIBYA TIBESTITIBESTI Aozou Bardaï SUDAN Zouar 20° Séguédine EASTERN CHAD . ASI ? .. .. .. .. .. Bilma . .. FAO . ... BORKOUBORKO. .U ... ENNEDIENNEDI OCHA B UNICEF J . .. .. .. ° . .. .. Faya-Largeau .. .... .... ..... NIGER . .. .. .. .. .. WFP/UNHAS ? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... ... .. .. .... WFP . ... .. WESTERN CHAD ... ... Fada .. ..... .. .... ASI ? . .... ACF . Committee d’Aide Médicale UNICEF J CORD WFP WADI FIRA Koro HIAS j D ICRC Toro CRS C ICRC G UNHCR Iriba 15 IFRC KANEMKANEM Arada WADIWADI FIRAFIRA J BAHRBAHR ELEL OUADDAÏ IMC ° Nokou Guéréda GAZELGAZEL Biltine ACTED Internews Nguigmi J Salal Am Zoer Mao BATHABATHA CRS C IRC JG Abéché Jesuit Refugee Service LACLAC IMC Bol Djédaa Ngouri Moussoro Oum Première Mentor Initiative Ati Hadjer OUADDAOOUADDAÏUADDAÏ Urgence OXFAM GB J Massakory IFRC IJ Refugee Ed. Trust HADJER-LAMISHADJER-LAMIS Am Dam Goz Mangalmé Première Urgence Bokoro Mongo Beïda UNHAS ? Maltam I Camp N'Djamena DARDAR SILASILA WCDO Gamboru-Ngala C UNHCR Maiduguri CHARI-CHARI- Koukou G Kousseri BAGUIRMIBAGUIRMI GUERAGUERA Angarana Massenya Dar Sila NIGERIA Melfi Abou Deïa ACTED Gélengdeng J Am Timan IMC MAYO-MAYO- Bongor KEBBIKEBBI SALAMATSALAMAT MENTOR 10° Fianga ESTEST Harazé WCDO SUDAN 10° Mangueigne C MAYO-MAYO- TANDJILETANDJILE MOYEN-CHARIMOYEN-CHARI