UF Health Jacksonville Technical Assistance Panel August 29 - 30 | Jacksonville, Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecting with Our Future from the Ground Up

Connecting With Our Future From The Ground Up 2018-19 ANNUAL REPORT Message from the CEO Dear Friends, Since joining Groundwork Jacksonville just over two years ago, I have We launched our first major campaign to raise $1.45 million for been overwhelmed by the outpouring of support we have received from design of the Model Project and the McCoys Creek branches, the all facets of the community. People and organizations that understand western-most portion of the creek not included in the City’s plans. access to clean green spaces and recreation, equitable housing and To date, we are two-thirds of the way to reaching that goal. economic opportunity, and an authentic connection to their community and to one another is vital for our city to thrive. Our Green Team Youth Corp Summer Apprenticeship continues to be a model not only among Groundwork Trusts but also for youth This past fiscal year, Groundwork has made tremendous leaps forward programs in our community. In addition to other important projects in our vision to build the Emerald Trail and restore our urban creeks. along the Emerald Trail, these teens were instrumental in helping RouxArt create the Sugar Hill Mosaic, the first of many public art As the City’s partner, Groundwork is spearheading the Emerald Trail with displays we intend to create. the first segment — the 1.3 mile Model Project — to be completed next year. I am especially grateful that the City has earmarked Emerald Trail And lastly, we launched the CREST program which was inspired construction funds in every year of the City’s Capital Improvement Plan by residents asking for ways to serve their community and improve (CIP) to maintain the trail’s exciting momentum. -

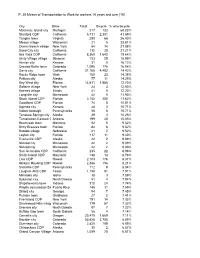

Copy of Censusdata

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

Shands Confidentiality Agreement

University of Florida College of Medicine – Jacksonville Visiting Student Application Checklist NAME: ROTATION: DATES: HOME SCHOOL: Do you need housing while rotating in Jacksonville? ______ YES ______ NO ***Housing is not guaranteed to visiting students, but we will make every effort to accommodate your request*** EMERGENCY CONTACT INFORMATION Name Phone Address ****Do NOT submit your application until all items have been completed**** Incomplete applications will not be considered – Submission Instructions on page 2 Students: Initial in each blank to certify each document has been completed and included in your application ________ Application for Extramural Course ________ Shands Confidentiality Agreement ________ Required Health Record ________ Parking Application* ________ Liability Confirmation Form ________ Copy of vehicle registration* ________ Background and Drug Screen Affidavit ________ CV/Resume ________ HIPAA Training Certificate ________ USMLE Step 1 Scores (MD/DO only) ________ UF Confidentiality Statement * If you plan to rent a vehicle, you may submit this document at check-in FOR OEA USE ONLY – STUDENTS: DO NOT WRITE BELOW THIS LINE Application Received Sent to Department Contract Obligations Insurance: SIP EX AI Dorm: No Yes / Invoice ________ Enter Applicant in NI ________ Application uploaded to NI ________ Computer access sent to student & coordinator NOTES UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA COLLEGE OF MEDICINE –JACKSONVILLE APPLICATION FOR EXTRAMURAL COURSE Mail Application to: Medical Student Administrator Office of Educational Affairs Kelsey Kyne (904) 244-5128 [email protected] c/o Student Administrator Medical Student Coordinator 653-1 W. 8th Street, Box L-15 Karen Sisco (904) 244-8233 [email protected] Jacksonville, FL 32209 Fax Numbers (904) 244-8997 OR (904) 244-4771 This form must be filled out completely – no substitute will be accepted – and must include the completed Required Health Record Section (page 2) before any rotation request will be considered. -

On-Demand CME/CE Activities Available International Stroke

7:00 AM 8:00 AM 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 11:00 AM 12:00 PM 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 3:00 PM 4:00 PM 5:00 PM 6:00 PM SCHEDULE-AT-A-GLANCE State-of-the-Science Stroke Nursing Symposium Pre-Conference Symposium I: Stroke in the Real World: Working Man Blues: Challenges in Inpatient Stroke Care Pre-Conference Symposium II (Student/Trainee/ TUES • FEB. 10 Early Career): Emerging Trends for Stroke Trials International Stroke Conference 2015 Symposia Symposia Targeting Spreading Door-to-needle or Depolarizations in Injured Call-to-needle Challenges Brain: Triggers, Modulators across Health Care Symposia Symposia and Causation Systems Problems with STAIRing Down the Barrel Interventions in Acute of a Loaded Research Gun: Cerebral Small Vessel Contralesional Stroke: 7 Little Things Disease in the Community: Hemisphere in Stroke How Useful Are the STAIR PLENARY SESSION I Criteria 15 Years Later? Prevalence, Causes and Recovery: Vascular and Cerebrovascular Vessel PROFESSOR-LED Clinical Relevance Neuronal Perspectives AHA’s CEO Welcome Wall Imaging: State of Improving Stroke Care for the Art Women POSTER TOUR Neuroinflammation and Childhood Stroke: AHA Presidential Cognitive Dysfunction in The Heart of the Matter Address Genetics and Stroke Moyamoaya Disease: SESSIONS Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Outcome Present and Future (60 MINS) Hemorrhage Oral Abstracts Thomas Willis Diagnosis of Stroke Lecture Oral Abstracts Reperfusion: The Latest, Emergency Care/Systems The Present, The Future REGULAR WED • FEB 11 Oral Abstracts Etiology Oral Abstracts I Late-Breaking Oral Abstracts -

Together for a Safe Campus

ANNUAL SECURITY AND FIRE SAFETY REPORT • 2019 TOGETHER FOR A SAFE CAMPUS UF HEALTH JACKSONVILLE CAMPUS • WWW.HSCJ.UFL.EDU Together for a Safe Campus: UF Health Jacksonville he University of Florida Police Department, a State of Florida and Nationally and Internationally accredited T law enforcement agency, was established to provide protection and service to the university community. We are committed to the prevention of crime and the protection of life and property; the preservation of peace, order, and safety; the enforcement of all laws and ordinances; and the safeguarding of your constitutional guarantees. The University of Florida Police Department is staffed by highly trained officers and Police Service Technicians (PSTs) who utilize only the very latest tools in the fight against crime to be better prepared to keep the campus community as safe as possible. The University of Florida has an array of services in place to promote an environment that is as crime-free as possible. We encourage you to familiarize yourself with these services and take advantage of them to help make your educational and living experience at the University of Florida as enjoyable and crime-free as possible. I encourage you to contact our Community Services Division at (352) 392-1409 and visit the department’s web site on-line at http://www.police.ufl.edu for additional information on available programs and services. — Chief Linda J. Stump-Kurnick Contents he UF Health Jacksonville Security Department is the main security provider for the University of Florida 2 Safety and Security a Shared T Health Jacksonville Campus. -

Grants Detail Schedule

THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION FOR NORTHEAST FLORIDA, INC. EIN: 59-6150746 Tax Year 2019 Form 990, Schedule I, Part II, Line 1, GRANTS AND OTHER ASSISTANCE IN EXCESS OF $5,000 TO GOVERNMENTS AND ORGANIZATIONS IN THE UNITED STATES 1(a) Name and Address of Grantee 1(b) EIN 1 ( C ) IRS Section Amount 1(h) Purpose of Grant 1 100 Black Men of Jacksonville, Inc. P.O. Box 2065 Jacksonville FL 32203 59-3190565 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(2) $9,742.00 for student scholarships support 50 students to attend the "Alabama: Education & History" Spring 2 100 Black Men of Jacksonville, Inc. P.O. Box 2065 Jacksonville FL 32203 59-3190565 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(2) $5,000.00 College tour. 3 100 Black Men of Jacksonville, Inc. P.O. Box 2065 Jacksonville FL 32203 59-3190565 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(2) $2,500.00 support the 2019 Urban Educarion Symposium 4 Adventures in God's Creation Inc. 115 1st Avenue N Jacksonville Beach FL 32250 80-0946172 Church $8,010.53 for general operating support 5 Adventures in God's Creation Inc. 115 1st Avenue N Jacksonville Beach FL 32250 80-0946172 Church $1,000.00 for general operating support 6 African American Mental Health Initiative 4210 Emerald Bay Drive Jacksonville FL 32277 47-4353349 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(1) $5,000.00 for general operating support to support the 2019 Mental Health and Village Talk promoting access to mental 7 African American Mental Health Initiative 4210 Emerald Bay Drive Jacksonville FL 32277 47-4353349 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(1) $3,500.00 health services in the African American community to provide goods and services to elderly person or for their direct benefit in 8 Aging True 4250 Lakeside Drive, Suite 116 Jacksonville FL 32210 59-6161532 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(2) $10,788.00 Duval County 9 Aging True 4250 Lakeside Drive, Suite 116 Jacksonville FL 32210 59-6161532 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(2) $912.75 to support Meals on Wheels 10 All Beaches Experimental Theatre 1015 Atlantic Blvd., #175 Atlantic Beach FL 32233 59-3212409 501(c)(3) / 509(a)(2) $5,200.00 to support the 2020 production of Souvenir 11 All Saints Church of Winter Park 338 E. -

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Recognizes 208 Hospital Units with Beacon Award for Excellence in 2020

Editorial Contact: Kristie Aylett AACN Communications 228-229-9472 [email protected] American Association of Critical-Care Nurses recognizes 208 hospital units with Beacon Award for Excellence in 2020 State Hospital, Unit, City (Award Level) StateAlabama Mobile Infirmary Medical Center, Neurology Step Down Unit, Mobile (Bronze) Mobile Infirmary Medical Center, Neurology Intensive Care Unit (ICU), Mobile (Bronze) North Baldwin Infirmary, The Birth Center, Bay Minette (Bronze) Arizona HonorHealth John C. Lincoln Medical Center, Specialty Surgical Care Unit, Phoenix (Gold) HonorHealth John C. Lincoln Medical Center, ICU, Phoenix (Silver) California Huntington Memorial Hospital, Critical Care Unit, Pasadena (Silver) Kaiser Permanente, Intermediate Cardiac Surgical Unit, Los Angeles (Gold) Little Company of Mary Hospital, Progressive Care Unit / Step Down Unit, Torrance (Silver) Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center, Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit, Pomona (Silver) Sharp Grossmont Hospital, Medical ICU, La Mesa (Gold) Sharp Memorial Hospital, Surgical ICU (2W), San Diego (Gold) St. Jude Medical Center, Critical Care Unit, Fullerton (Silver) UCLA Medical Center, 6ICU - Neuroscience / Trauma ICU, Los Angeles (Silver) UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center, 4MN, Santa Monica (Silver) Colorado Denver Health Medical Center, Surgical ICU, Denver (Silver) Connecticut Hospital of St. Raphael, Medical ICU-SRC, New Haven (Silver) Delaware Christiana Care Health System, Transitional Medical Unit, Newark (Silver) District of Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, C61 Neurosciences and Stroke IMC, Columbia Washington (Gold) Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, C41, Washington (Silver) Florida Baptist Health South Florida, Baptist Health Telehealth Center, Coral Gables (Gold) Baptist Hospital of Miami, Critical Care Center, Miami (Gold) Baptist Hospital of Miami, Neonatal ICU, Miami (Silver) Baptist Medical Center, T4A MSICU, Jacksonville (Silver) Dr. -

Table S1. Participating Centers Huntsville Hospital Alabama Baptist Medical Center East Alabama St. Vincent Birmingham Alabama T

Table S1. Participating Centers Huntsville Hospital Alabama Baptist Medical Center East Alabama St. Vincent Birmingham Alabama The Children's Hospital at Providence, Alaska Alaska St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center Arizona Cardon Children's Medical Center Arizona Banner Thunderbird Medical Center Arizona Banner Estrella Medical Center Arizona Abrazo Arrowhead Campus Arizona Arizona Children's Center Maricopa Integrated Health Arizona Flagstaff Medical Center Arizona Willow Creek Women's Hospital Arkansas University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Arkansas Mercy Hospital Fort Smith Arkansas Providence Tarzana Medical Center California Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center California Rocky Mountain Hospital for Children at Presbyterian/Saint Luke’s Colorado St. Mary's Hospital and Medical Center Colorado Swedish Medical Center Colorado Poudre Valley Hospital Colorado Good Samaritan Medical Center Colorado Denver Health Medical Center Colorado Stamford Hospital Connecticut Danbury Hospital Connecticut Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital Connecticut Connecticut Children's NICU at UCONN Health Center Connecticut Norwalk Hospital Connecticut The Hospital of Central Connecticut Connecticut Greenwich Hospital Connecticut Washington Hospital Center District of Columbia Joe DiMaggio Children's Hospital Florida Florida Hospital for Children Florida Sacred Heart Health System Florida Baptist Children's Hospital Florida St. Joseph's Children's Hospital Florida Women's Center at Florida Hospital - Tampa Florida UF Shands Hospital Gainesville Florida UF Health Jacksonville Florida North Florida Regional Medical Center, Inc. Florida Gwinnett Hospital System Georgia The Medical Center at Columbus Regional Georgia Piedmont Rockdale Hospital Georgia Hamilton Medical Center Georgia Floyd Medical Center Georgia Kapiolani Medical Center for Women & Children Hawaii St. Luke's Regional Medical Center Idaho St. -

Northwest Jacksonville Community Quality-Of-Life Plan Planning Task Force: Individuals Mario Akinson • William Atkinson • Dr

Northwest Jacksonville Community Quality-of-Life Plan Planning Task Force: Individuals Mario Akinson • William Atkinson • Dr. Willie Alexander • Annie Mae Badceu • Franiceni Barlin • Eunice Barnum • Andre Benn • Malachi Beyah • Curtis Booner • Jerry Box • James Breaker • Tina Brooks • Congresswoman Corrine Brown • Jenista D. Brown • Justin Brown • Mickee Brown • Gadson Burgess • Ozola Burgess • Jim Capraro • Min. Lamonte Carter • Dellafay Chafin • Tony Chafin • Daphne Colbert • Daunice Collins • Kenneth (Ken) Covington • Rory Cummings • Theresa Cummings • Felicia Dantzler • Eugene Darius • Joan Davenport • Dara Davis • Lorenzo Denmark • Mickel Dosher • Matice Dozin • Mary Eaves • Vincent Edmonds • Annie Mae Edwards • E’shekinah (Esha) El’shrief • Je’Toye Flornoy • Robert Flornoy • Geraldine (Gerrie) Ford-Hardin • Gwen Gamble • Aileen Gibbs • Pat Goffe • Deborah Green • Kendalyn Green • Darrell Griffin • Dwayne Griffin • Sadie Guinyard • Zauhaier Hamami • Gail Hannons • Zoeshair H. • Douglas Harrell • Greta Harris • Lakeeisha Heggs • Marvine Heggs • Giovanni Henderson • Patricia Henry • Carolyn B. Herring • Shevonia M. Hewell • Nancya Hicks • Janice Hightower • Yolanda Hightower • Kenderson Hill • Derrick Hogan • Samuel Holman • Juanita Horne • Shevonica M. Howell • Joseph James • Valerie Jenkins • Staff at Job Corps • Arvin Johnson • Clifford Johnson Jr. • Ebony Johnson • Mildred Johnson • Warren Jones • Betty Kimble • Janice Knightwater • Derla Labberte • Vivian Lanham • Reggie Lott • Willie Lyons • Annie MacEdwards • Joann Manning • -

Appendix A: Historic Context and References

APPENDIX A: HISTORIC CONTEXT AND REFERENCES FROM THE HISTORIC PROPERTIES RESURVEY, CITY OF FERNANDINA BEACH, NASSAU COUNTY, FLORIDA, BLAND AND ASSOCIATES, INC. 2007 Colonial Period, 1565-1821 Founded in the early nineteenth century and incorporated in 1824, Fernandina Beach is one of Florida's oldest cities. The principal city of Nassau County, Fernandina Beach is located on the north end of Amelia Island, which has a colonial heritage associated with early French explorers, the First Spanish period, the British period, and the Second Spanish period. Early French explorers named the island "Isle de Mai" and Pedro Menendez built a fort there in 1567. In 1598 and 1675, Spanish missions built on the island contributed to a larger system implemented by the Spanish Crown to convert the Indians to Catholicism. In 1702, an English incursion from Charleston, South Carolina, attacked St. Augustine, but also invaded an outpost on the island and threatened the missions. Later, in 1735, when James Oglethorpe attempted to secure the St. Marys River as the southern boundary of his new colony, the Georgian scouted the island, which he named Amelia for one of King George II's daughters (Johannes 2000:3-4). Between 1513 and 1763, Spain failed to settle permanently any area of Florida except the immediate environs of St. Augustine. Besides establishing a permanent base at the port city and a chain of missions into the interior, the Spanish accomplished little of lasting significance. Farmers and ranchers cleared land for cattle, and planted crops and fruit trees. But, the growth of English colonies to the north in the 1700s and forays by settlers and militia into Florida destabilized Spain's nascent agricultural economy and mission system. -

FY 2011-2012 Program Outcomes Report

Program Outcomes Report FY 2011-12 Partnering for outcomes that support children and families Jacksonville Children’s Commission Program Outcomes FY 2011-12 The Jacksonville Children’s Commission (the Commission) is pleased to provide this detailed program outcomes report as a supplement to our FY 2011-12 Annual Report. This report provides specific detail on early childhood, youth development, assistance for special needs and family programs funded by the Commission during FY 2011-12. The Commission is a semi-autonomous body within the Executive Branch of the City of Jacksonville. The Commission serves as the central focus for the evaluation, planning and distribution of the city’s funds for children and is also responsible for applying for state, federal and private funds for children’s programs. The Commission recognizes its responsibility to invest in our city’s most precious resource, our children. We work hand in hand with local nonprofit organizations to improve the health and lives of children living in Duval County. The Commission carefully monitors all programs that it funds and closely tracks program effectiveness and outcomes. The Jacksonville Children’s Commission focuses on prevention and early intervention programs so that children: have stable nurturing families; are entering kindergarten ready to learn; have high quality programs after school and during the summer; and get specialized help when they need it. These programs are proven to reduce the downstream costs of special education, foster care, juvenile justice and youth incarceration. This report provides a picture of the children and families served in Commission-funded programs. Within it you will find detailed demographics for participants served, geographic maps to reference program locations throughout the city, and the funding provided to each program. -

Jacksonville

MOVING UP IN THE BOLD CITY Community Leaders Igniting Mobility WELCOME Jacksonville has a bright future on the horizon with new developments in our Downtown and historic neighborhoods: from bright new ideas for our waterfront, an ambitious new transit center, an expanding vision for our sports district, to restoration of historic buildings. We are the Bold City of dreamers and doers. And, while we are building on a long legacy of innovation and rich vision, we have struggled to offer every resident of Jacksonville an equal opportunity to share in this vision. JOIN US Like many other cities across the South, we have struggled with the legacy of poverty and oppression. Simultaneously, we have wrestled with intergenerational poverty. In 2015, 37% of Jacksonville Households Launch Event were either living in poverty or struggling to afford basic needs, and 66% of children born to a Jacksonville August 25, 2018 family living in the lowest 20% of the economic spectrum will spend their lives in poverty.1 10 a.m. - 1 p.m. Weaver Center for This is why we believe increasing upward economic mobility needs to be a central focus as we continue Community Outreach to grow and develop as a city. By actively viewing economic mobility as a necessary feature of our growth and development we can continue to build our vision, while dismantling our legacy of intergenerational poverty. We can lift each other up, and move forward, together. Community Forum 1 New Town In order for meaningful change in economic mobility to occur in Jacksonville, we believe that community September 27, 2018 engagement is essential.