Early Families of Upper Matecumbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FWC Division of Law Enforcement South Region

FWC Division of Law Enforcement South Region – Bravo South Region B Comprised of: • Major Alfredo Escanio • Captain Patrick Langley (Key West to Marathon) – Lieutenants Roy Payne, George Cabanas, Ryan Smith, Josh Peters (Sanctuary), Kim Dipre • Captain David Dipre (Marathon to Dade County) – Lieutenants Elizabeth Riesz, David McDaniel, David Robison, Al Maza • Pilot – Officer Daniel Willman • Investigators – Carlo Morato, John Brown, Jeremy Munkelt, Bryan Fugate, Racquel Daniels • 33 Officers • Erik Steinmetz • Seth Wingard • Wade Hefner • Oliver Adams • William Burns • John Conlin • Janette Costoya • Andy Cox • Bret Swenson • Robb Mitchell • Rewa DeBrule • James Johnson • Robert Dube • Kyle Mason • Michael Mattson • Michael Bulger • Danielle Bogue • Steve Golden • Christopher Mattson • Steve Dion • Michael McKay • Jose Lopez • Scott Larosa • Jason Richards • Ed Maldonado • Adam Garrison • Jason Rafter • Marty Messier • Sebastian Dri • Raul Pena-Lopez • Douglas Krieger • Glen Way • Clayton Wagner NOAA Offshore Vessel Peter Gladding 2 NOAA near shore Patrol Vessels FWC Sanctuary Officers State Law Enforcement Authority: F. S. 379.1025 – Powers of the Commission F. S. 379.336 – Citizens with violations outside of state boundaries F. S. 372.3311 – Police Power of the Commission F. S. 910.006 – State Special Maritime Jurisdiction Federal Law Enforcement Authority: U.S. Department of Commerce - National Marine Fisheries Service U.S. Department of the Interior - U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Treasury - U.S. Customs Service -

Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets

Keys TravelerThe Magazine Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets fla-keys.com Decompresssing at Bahia Honda State Park near Big Pine Key in the Lower Florida Keys. ANDY NEWMAN MARIA NEWMAN Keys Traveler 12 The Magazine Editor Andy Newman Managing Editor 8 4 Carol Shaughnessy ROB O’NEAL ROB Copy Editor Buck Banks Writers Julie Botteri We do! Briana Ciraulo Chloe Lykes TIM GROLLIMUND “Keys Traveler” is published by the Monroe County Tourist Development Contents Council, the official visitor marketing agency for the Florida Keys & Key West. 4 Sanctuary Protects Keys Marine Resources Director 8 Outdoor Art Enriches the Florida Keys Harold Wheeler 9 Epic Keys: Kiteboarding and Wakeboarding Director of Sales Stacey Mitchell 10 That Florida Keys Sunset! Florida Keys & Key West 12 Keys National Parks Join Centennial Celebration Visitor Information www.fla-keys.com 14 Florida Bay is a Must-Do Angling Experience www.fla-keys.co.uk 16 Race Over Water During Key Largo Bridge Run www.fla-keys.de www.fla-keys.it 17 What’s in a Name? In Marathon, Plenty! www.fla-keys.ie 18 Visit Indian and Lignumvitae Keys Splash or Relax at Keys Beaches www.fla-keys.fr New Arts District Enlivens Key West ach of the Florida Keys’ regions, from Key Largo Bahia Honda State Park, located in the Lower Keys www.fla-keys.nl www.fla-keys.be Stroll Back in Time at Crane Point to Key West, features sandy beaches for relaxing, between MMs 36 and 37. The beaches of Bahia Honda Toll-Free in the U.S. -

Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan

Monroe County Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Prepared for Monroe County by Camp Dresser & McKee, Inc. August 2001 file:///F|/GSG/PDF Files/Stormwater/SMMPCover.htm [12/31/2001 3:10:29 PM] Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Acknowledgements Monroe County Commissioners Dixie Spehar (District 1) George Neugent, Mayor (District 2) Charles "Sonny" McCoy (District 3) Nora Williams, Mayor Pro Tem (District 4) Murray Nelson (District 5) Monroe County Staff Tim McGarry, Director, Growth Management Division George Garrett, Director, Marine Resources Department Dave Koppel, Director, Engineering Department Stormwater Technical Advisory Committee Richard Alleman, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Paul Linton, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Murray Miller, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Dave Fernandez, Director of Utilities, City of Key West Roland Flowers, City of Key West Richard Harvey, South Florida Office U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Ann Lazar, Department of Community Affairs Erik Orsak, Environmental Contaminants, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Gus Rios, Dept. of Environmental Protection Debbie Peterson, Planning Department, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Teresa Tinker, Office of Planning and Budgeting, Executive Office of the Governor Eric Livingston, Bureau Chief, Watershed Mgmt, Dept. of Environmental Protection AB i C:\Documents and Settings\mcclellandsi\My Documents\Projects\SIM Projects\Monroe County SMMP\Volume 1 Data & Objectives Report\Task I Report\Acknowledgements.doc Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Stormwater Technical Advisory Committee (continued) Charles Baldwin, Islamorada, Village of Islands Greg Tindle, Islamorada, Village of Islands Zulie Williams, Islamorada, Village of Islands Ricardo Salazar, Department of Transportation Cathy Owen, Dept. of Transportation Bill Botten, Mayor, Key Colony Beach Carlos de Rojas, Regulation Department, South Florida WMD Tony Waterhouse, Regulation Department, South Florida WMD Robert Brock, Everglades National Park, S. -

Mile Marker 0-65 (Lower Keys)

Key to Map: Map is not to scale Existing Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail Aquatic Preserves or Alternate Path Overseas Paddling Trail U.S. 1 Point of Interest U.S. Highway 1 TO MIAMI Kayak/Canoe Launch Site CARD SOUND RD Additional Paths and Lanes TO N KEY LARGO Chamber of Commerce (Future) Trailhead or Rest Area Information Center Key Largo Dagny Johnson Trailhead Mangroves Key Largo Hammock Historic Bridge-Fishing Botanical State Park Islands Historic Bridge Garden Cove MM Mile Marker Rattlesnake Key MM 105 Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Greenways & Trails Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail Office: (305) 853-3571 Key Largo Adams Waterway FloridaGreenwaysAndTrails.com El Radabob Key John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park MM 100 Swash Friendship Park Keys Key Largo Community Park Florida Keys Community of Key Largo FLORIDA BAY MM 95 Rodriguez Key Sunset Park Dove Key Overseas Heritage Trail Town of Tavernier Harry Harris Park Burton Drive/Bicycle Lane MM 90 Tavernier Key Plantation Key Tavernier Creek Lignumvitae Key Aquatic Preserve Founders Park ATLANTIC OCEAN Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park MM 85 Snake Creek Long Key Historic Bridge TO UPPER Islamorada, Village of Islands Whale Harbor Channel GULF OF MEXICO KEYS Tom's Harbor Cut Historic Bridge Wayside Rest Area Upper Matecumbe Key Tom's Harbor Channel Historic Bridge MM 80 Dolphin Research Center Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park Tea Table Key Relief Channel Grassy Key MM 60 Conch Keys Tea Table Channel Grassy Key Rest Area Indian Key -

03.01.2012 WKFRGSP AP.Pdf

Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park APPROVED Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks March 1, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK .....................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN ......................................................................2 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................................8 Management Authority and Responsibility ..............................................................8 Park Management Goals ..............................................................................................9 Management Coordination ........................................................................................10 Public Participation .....................................................................................................10 Other Designations ......................................................................................................10 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................11 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT .................................................12 Natural Resources .......................................................................................................12 Topography -

Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park

Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park 2020 PARK FACTS VISITATION ECONOMIC LOCAL JOBS STAFF VOLUNTEERS ACRES IMPACT SUPPORTED 11,273 $1,115,718 16 2* 4 356 *2 Staff manage three parks - Indian Key Historic State Park, San Pedro Underwater Archaeological Preserve State Park, and Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park Formed of Key Largo limestone, fossilized coral, this land was sold to the Florida East Coast Railroad, which used the stone to build Henry Flagler's Overseas Railroad in the early 1900s. Plan your visit at FloridaStateParks.org This information fact sheet was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation (FloridaStateParksFoundation.org) FLORIDA STATE PARKS A MAJOR CONTRIBUTOR TO FLORIDA’S WELL-BEING! The Florida State Parks and Trails system is one of the state’s greatest success stories having won the prestigious National Gold Medal of Excellence a record four times. Florida residents and visitors from around the world are drawn to Florida’s state parks and trails as the places to hike, bike, kayak, swim, fish, camp, lay on the beach, hunt for shells, learn about nature and Florida history, have family reunions, and even get married! Plan your visit at FloridaStateParks.org 2020 Statewide Economic Data ● 175 Florida State Parks and Trails ● $150 million in sales tax revenue (164 Parks / 11 Trails comprising nearly 800,000 acres) ● 31,810 jobs supported ● $2.2 billion direct economic impact ● 25 million visitors served FRIENDS OF ISLAMORADA AREA STATE PARKS The friends group established in 1987, supports six state parks in the Florida Keys – Long Key, Curry Hammock, San Pedro Underwater Archaeological Preserve,Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological, Indian Key and Lignumvitae Key Botanical. -

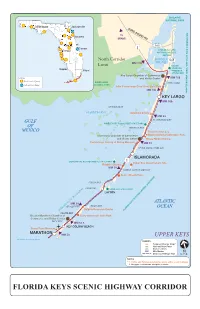

FL Keys Application Map 11X17.Ai

BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK Tallahassee Jacksonville CARD SOUND RD To Daytona MIAMI Orlando 905 Cocoa 1 Tampa CROCODILE LAKE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE North Corridor BARNES 905 MM 110 SOUND Limit DAGNY Naples JOHNSON Miami HAMMOCK STATE PARK Key Largo Chamber of Commerce LEGEND and Visitor Center MM 106 Florida Scenic Highway EVERGLADES KEY LARGO National Scenic Byway NATIONAL PARK John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park MM 102 JOHN PENNEKAMP CORAL REEF STATE PARK (UNDERWATER) KEY LARGO MM 100 OYSTER KEYS FLORIDA BAY Wild Bird Center MM 93 GULF PLANTATION KEY WINDLEY KEY FOSSIL REEF STATE PARK OF WINDLEY KEY MEXICO Theater of the Sea Islamorada Chamber of Commerce Marine Mammal Adventure Park and Visitor Center Whale Harbor Marina Florida Keys History of Diving Museum MM 83 UPPER MATECUMBE KEY ISLAMORADA LIGNUMVITAE KEY BOTANICAL STATE PARK 1 Indian Key State Historic Site Robbie’s Marina MM 78 LOWER MATECUMBE KEY Anne’s Beach Park ARY FIESTA KEY LONG KEY LONG KEY STATE PARK LAYTON ATLANTIC MM 59 GRASSY KEY DUCK KEY OCEAN Dolphin Research Center INTRACOASTAL WATERWAY FLORIDA KEYS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTU CRAWL KEY Greater Marathon Chamber of Curry Hammock State Park Commerce and Visitor Center VACA KEY MM 53.5 KEY COLONY BEACH Crane Point Museum MARATHON MM 50 UPPER KEYS continued on next page LEGEND xxx Features/Itinerary Stops* xxx National/State Parks xxx Visitor Centers MM Mile Marker Overseas Heritage Trail NOTES * 1. Diving and Fishing opportunities along entire scenic highway. 2. No gaps or intrusions along the corridor. FLORIDA KEYS SCENIC -

Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park

Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park 2018 PARK FACTS VISITATION ECONOMIC LOCAL JOBS STAFF VOLUNTEERS ACRES IMPACT SUPPORTED 7,803 693,335 10 2* 0 356 *2 Staff manage three parks - Indian Key Historic State Park, San Pedro Underwater Archaeological Preserve State Park, and Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park Formed of Key Largo limestone, fossilized coral, this land was sold to the Florida East Coast Railroad, which used the stone to build Henry Flagler's Overseas Railroad in the early 1900s. Plan your visit at FloridaStateParks.org This information fact sheet was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, 2019 (FloridaStateParksFoundation.org) FLORIDA STATE PARKS A MAJOR CONTRIBUTOR TO FLORIDA’S WELL-BEING! The system of Florida State Parks and Trails is one of the state’s greatest success stories. It’s the ONLY system in the nation thrice awarded the Gold Medal of Excellence by its national peer group. Florida residents and visitors from around the world are drawn to Florida’s state parks and trails as the places to hike, bike, kayak, swim, fish, camp, lay on the beach, hunt for shells, learn about nature and Florida history, have family reunions, and even get married! Plan your visit at FloridaStateParks.org. 2018 Statewide Economic Data ⚫ 175 Florida State Parks and Trails ⚫ $158 million in sales tax revenue (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 acres ⚫ 33,587 jobs supported ⚫ $2.4 billion direct economic impact ⚫ Over 28 million visitors served __________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRIENDS OF ISLAMORADA AREA STATE PARKS The friends group established in 1987, supports six state parks in the Florida Keys – Long Key, Curry Hammock, San Pedro Underwater Archaeological Preserve,Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological, Indian Key and Lignumvitae Key Botanical. -

MCTG-2753 ENGLISH Conch Brochure

For More Information KEY LARGO CHAMBER OF COMMERCE (305) The Florida Keys & Key West. Come as you are. FLORIDA KEYS VISITOR CENTER (305) 451-1414 [email protected]/[email protected] Milemarker 106, Overseas Hwy. Key Largo, FL 3451-14143037, U.S. ISLAMORADA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 305-664-4503305-664-4503/[email protected]@islamoradachamber.org Compose your vacation in any Key. Milemarker 82.6, Overseas Hwy., P.O. Box 915 Islamorada, FL 33036, U.S. MARATHON CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ((305)305 )743-5417 743-5417/[email protected]@floridakeysmarathon.com Milemarker 53, Overseas Hwy. Marathon, FL 33050, U.S. LOWER KEYS CHAMBER OF COMMERCE (305) 872-2411/[email protected] (305) 872-2411 [email protected] KEY LARGO ISLAMORADA MARATHON LOWER KEYS KEY WEST Milemarker 31, Overseas Hwy. Big Pine Key, FL 33040, U.S. Sport Fishing Your Hometown in the KEY WEST CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ((305)305 )294-2587 [email protected]/[email protected] Dive Capital of the World. A Natural Escape. The Uncommon Place. 510 Greene Street, Key West, FL 33040, U.S. Capital of the World. Heart of the Keys. FLORIDA KEYS & KEY WEST TOURIST DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL (305) 296-1552/1-800-FLA-KEYS P.O. Box 866, Key West, FL 33041, U.S. Directions BY AIR: TheThe KeyKey WestWest IInternationalnternationa lAirport Airpor hast ha scommercial commerci aservicel servic ande and is iserveds serve dby b y major airlines. Bmajor airlines.oth the Key We Bothst and the M aKeyrat hWeston a iandrpo rMarathonts have ch airportsarter se rhavevice, chartergenera lservice, aviatio n and rental service. -

Florida Keys Mile-Marker Guide

Road Trip: Florida Keys Mile-Marker Guide Overseas Highway, mile by mile: Plan your Florida Keys itinerary The Overseas Highway through the Florida Keys is the ultimate road trip: Spectacular views and things to do, places to go and places to hide, hidden harbors and funky tiki bars. There are hundreds of places to pull over to fish or kayak or enjoy a cocktail at sunset. There are dozens of colorful coral reefs to snorkel or dive. Fresh seafood is a Florida Keys staple, offered at roadside fish shacks and upscale eateries. For many, the destination is Key West, at the end of the road, but you’ll find the true character of the Florida Keys before you get there. This mile-marker guide will help you discover new things to see and do in the Florida Keys. It’s a great tool for planning your Florida Keys driving itinerary. Card Sound Road 127.5 — Florida City – Junction with Fla. Turnpike and U.S. 1. 126.5 — Card Sound Road (CR-905) goes east to the Card Sound Bridge and northern Key Largo. If you’re not in a hurry, take the toll road ($1 toll). Card Sound Road traverses a wild area that once had a small community of Card Sound. All that’s left now is Alabama Jack’s, a funky outdoor restaurant and tiki bar known for its conch fritters and the line of motorcycles it attracts. (Don’t be afraid; it’s a family oriented place and great fun.) If you take Card Sound Road, you’ll pass a little-known park, Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park, before coming to Key Largo itself. -

Florida Keys Regional Working Group

Florida Keys Regional Working Group MONROE COUNTY (part) The Florida Keys Regional Working Group liaison is Alison Higgins, The Nature Conservancy, P.O. Box 420237, Summerland Key, Florida, 33042, phone: 305-745-8402, fax: 305-745-8399, e-mail: [email protected] 30 Key West Naval Air Station County: Monroe PCL Size: 6,323 Project ID: FK-046 18.65 acres $73,177.76 Project ID: FK-053 45.00 acres $24,691.15 Project Manager: U.S. Navy Edward Barham, Natural Resources Manager Post Office Box 9007, Key West, Florida 33040-9007 Phone: 305-293-2911, Fax: 305-293-2542 E-mail: [email protected] Two projects occurred at Key West NAS; one for initial control and one for maintenance control. Initial control conducted on Big Coppitt Key and Geiger Key targeted Australian pine. Big Coppitt Key is a filled, scarified area within the Key West NAS Fish and Wildlife Management Area MU-5. The site is approximately 0.65 acres and is adjacent to mangrove wetlands and open water. Geiger Key is a former “Hawk Missile Site” and comprises approximately 18 acres. The second project area encompassed a natural beach berm along the Atlantic Ocean located on Key West NAS property on Boca Chica and Geiger Keys. This area is habitat for wildlife, including the endangered Lower Keys marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris hefneri). Rapidly expanding populations of invasive exotic plant species infested the beach berm. The two primary invaders were lather leaf and Brazilian pepper. Also present, to a much lesser extent, were Australian pine and seaside mahoe. -

June 2019 Monthly Bacteriological Reports

FKAA BACTERIA MONTHLY REPORT PWSID# 4134357 MONTH: June 2019 H.R.S. LAB # E56717 & E55757 MMO‐MUG/ Cl2 pH RETEST MMO‐MUG/ 100ML DATE 100ML Cl2 SERVICE AREA # 1 S.I. LAB Date Sampled: 6/4/2019 125 Las Salinas Condo‐3930 S. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.4 9.20 126 Key West by the Seas Condo‐2601 S. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.2 9.15 127 Advanced Discount Auto Parts‐1835 Flagler Ave. A 3.0 9.10 128 1800 Atlantic Condo‐1800 Atlantic Blvd. A 3.3 9.16 129 807 Washington St. (#101) A 3.1 9.10 130 The Reach Resort‐1435 Simonton St. A 3.3 9.14 131 Dewey House‐504 South St. A 3.4 9.14 132 Almond Tree Inn‐512 Truman Ave. A 3.5 9.18 133 Harbor Place Condo‐107 Front St. A 3.4 9.17 134 Court House‐302 Fleming St. A 3.2 9.14 135 Old Town Trolley Barn‐126 Simonton St. A 3.2 9.14 136 Land's End Village‐ #2 William St. A 3.6 9.21 137 U.S. Navy Peary Court Housing‐White/Southard St. A 3.2 9.12 138 Dion's Quick Mart‐1000 White St. A 2.9 9.19 139 Bayview Park‐1400 Truman Ave. A 3.3 9.14 140 Mellow Ventures‐1601 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.3 9.23 141 VFW Post 3911‐2200 N.Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.3 9.24 143 US Navy Sigsbee Park Car Wash‐Felton Rd. A 2.8 9.19 144 Conch Scoops‐3214 N.