Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

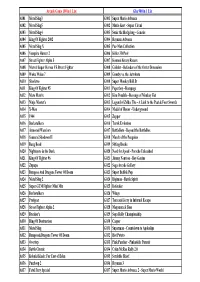

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Acid Drop Actionauts Activision Decathlon, The Adventure Adventures of TRON Air Raid Air Raiders Airlock Air-Sea Battle Alfred Challenge Alien Alien Greed Alien Greed 2 Alien Greed 3 Allia Quest Alligator People, The Alpha Beam with Ernie Amidar Aquaventure Armor Ambush Artillery Duel AStar Asterix Asteroid Fire Asteroids Astroblast Astrowar Atari Video Cube A-Team, The Atlantis Atlantis II Atom Smasher A-VCS-tec Challenge AVGN K.O. Boxing Bachelor Party Bachelorette Party Backfire Backgammon Bank Heist Barnstorming Base Attack Basic Math BASIC Programming Basketball Battlezone Beamrider Beany Bopper Beat 'Em & Eat 'Em Bee-Ball Berenstain Bears Bermuda Triangle Berzerk Big Bird's Egg Catch Bionic Breakthrough Blackjack BLiP Football Bloody Human Freeway Blueprint BMX Air Master Bobby Is Going Home Boggle Boing! Boulder Dash Bowling Boxing Brain Games Breakout Bridge Buck Rogers - Planet of Zoom Bugs Bugs Bunny Bump 'n' Jump Bumper Bash BurgerTime Burning Desire Cabbage Patch Kids - Adventures in the Park Cakewalk California Games Canyon Bomber Carnival Casino Cat Trax Cathouse Blues Cave In Centipede Challenge Challenge of.... Nexar, The Championship Soccer Chase the Chuckwagon Checkers Cheese China Syndrome Chopper Command Chuck Norris Superkicks Circus Atari Climber 5 Coco Nuts Codebreaker Colony 7 Combat Combat Two Commando Commando Raid Communist Mutants from Space CompuMate Computer Chess Condor Attack Confrontation Congo Bongo Conquest of Mars Cookie Monster Munch Cosmic -

GAMELIST ARCADE 32 Ver.FM2-082020

GAMELIST ARCADE 32 ver.FM2-082020 Attento! I giochi non sono in ordine alfabetico ma raggruppati per console originale. Apri questa lista con un lettore PDF (ad esempio adobe reader) e usa il tasto “cerca” per trovare i tuoi giochi preferiti! I giochi della sala giochi sono nei gruppi “Mame”, “Neo-geo” e “Arcade”. Arcade Pag. 2 NeoGeo Pocket Color Pag. 78 Atari Lynx Pag. 21 NeoGeo Pocket Pag. 78 Atari2600 Pag. 22 Neogeo Pag. 79 Atari5200 Pag. 27 NES Pag. 83 Atari7800 Pag. 28 Nintendo 64 Pag. 100 Game Boy Advance Pag. 29 PC-Engine Pag. 100 Game Boy Color Pag. 37 Sega 32X Pag. 104 Game Boy Pag. 44 Sega Master System Pag. 104 Game Gear Pag. 55 Sega Mega Drive Pag. 109 Mame Pag. 61 SNES Pag. 122 PLAYSTATION Pag. 136 DREAMCAST Pag. 136 SEGA CD Pag. 136 1 ARCADE ( 1564 ) 1. 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally 42. Alien Storm (World, 2 Players, FD1094 (94/07/18) 317-0154) 2. 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Alien Syndrome (set 4, System 16B, 3. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) unprotected) 4. 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 44. Alien VS Predator (Euro 940520) 5. 1943: The Battle of Midway Mark II (US) 45. Aliens (World set 1) 6. 1944 : The Loop Master (USA 000620) 46. Alligator Hunt (World, protected) 7. 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) 47. Altered Beast (set 8, 8751 317-0078) 8. 1991 Spikes 48. Ambush 9. 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 49. American Horseshoes (US) 10. 4 En Raya (set 1) 50. -

JAM-BOX Retro PACK 64GB AMSTRAD

JAM-BOX retro PACK 64GB BMX Simulator (UK) (1987).zip BMX Simulator 2 (UK) (19xx).zip Baby Jo Going Home (UK) (1991).zip Bad Dudes Vs Dragon Ninja (UK) (1988).zip Barbarian 1 (UK) (1987).zip Barbarian 2 (UK) (1989).zip Bards Tale (UK) (1988) (Disk 1 of 2).zip Barry McGuigans Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Batman (UK) (1986).zip Batman - The Movie (UK) (1989).zip Beachhead (UK) (1985).zip Bedlam (UK) (1988).zip Beyond the Ice Palace (UK) (1988).zip Blagger (UK) (1985).zip Blasteroids (UK) (1989).zip Bloodwych (UK) (1990).zip Bomb Jack (UK) (1986).zip Bomb Jack 2 (UK) (1987).zip AMSTRAD CPC Bonanza Bros (UK) (1991).zip 180 Darts (UK) (1986).zip Booty (UK) (1986).zip 1942 (UK) (1986).zip Bravestarr (UK) (1987).zip 1943 (UK) (1988).zip Breakthru (UK) (1986).zip 3D Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Bride of Frankenstein (UK) (1987).zip 3D Grand Prix (UK) (1985).zip Bruce Lee (UK) (1984).zip 3D Star Fighter (UK) (1987).zip Bubble Bobble (UK) (1987).zip 3D Stunt Rider (UK) (1985).zip Buffalo Bills Wild West Show (UK) (1989).zip Ace (UK) (1987).zip Buggy Boy (UK) (1987).zip Ace 2 (UK) (1987).zip Cabal (UK) (1989).zip Ace of Aces (UK) (1985).zip Carlos Sainz (S) (1990).zip Advanced OCP Art Studio V2.4 (UK) (1986).zip Cauldron (UK) (1985).zip Advanced Pinball Simulator (UK) (1988).zip Cauldron 2 (S) (1986).zip Advanced Tactical Fighter (UK) (1986).zip Championship Sprint (UK) (1986).zip After the War (S) (1989).zip Chase HQ (UK) (1989).zip Afterburner (UK) (1988).zip Chessmaster 2000 (UK) (1990).zip Airwolf (UK) (1985).zip Chevy Chase (UK) (1991).zip Airwolf 2 (UK) -

Arcade Games Arcade Blaster List

Arcade Games Arcade Blaster List 005 Aliens 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally All American Football 10‐Yard Fight Alley Master 1942 Alpha Fighter / Head On 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen Alpha Mission II / ASO II ‐ Last Guardian 1943: The Battle of Midway Alpine Ski 1944: The Loop Master Amazing Maze 1945k III Ambush 19XX: The War Against Destiny American Horseshoes 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge American Speedway 2020 Super Baseball AmeriDarts 3 Count Bout Amidar 4 En Raya Andro Dunos 4 Fun in 1 Angel Kids 4‐D Warriors Anteater 64th. Street ‐ A Detective Story Apache 3 720 Degrees APB ‐ All Points Bulletin 800 Fathoms Appoooh 88 Games Aqua Jack 99: The Last War Aqua Rush 9‐Ball Shootout Aquarium A. D. 2083 Arabian A.B. Cop Arabian Fight Ace Arabian Magic Acrobat Mission Arcade Classics Acrobatic Dog‐Fight Arch Rivals Act‐Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon Argus Action Fighter Argus Action Hollywood Ark Area Aero Fighters Arkanoid ‐ Revenge of DOH Aero Fighters 2 / Sonic Wings 2 Arkanoid Aero Fighters 3 / Sonic Wings 3 Arkanoid Returns After Burner Arlington Horse Racing After Burner II Arm Wrestling Agent Super Bond Armed Formation Aggressors of Dark Kombat Armed Police Batrider Ah Eikou no Koshien Armor Attack Air Attack Armored Car Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Armored Warriors Air Duel Art of Fighting Air Gallet Art of Fighting 2 Air Rescue Art of Fighting 3 ‐ The Path of the Warrior Airwolf Ashura Blaster Ajax ASO ‐ Armored Scrum Object Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Assault Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Asterix Alien Arena Asteroids Alien Syndrome Asteroids Deluxe Alien vs. -

My Games Room Arcade Games Ultra Edition Games List

My Games Room Arcade Games Ultra Edition Games List 005 Air Duel 1 on 1 Government Air Gallet 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally Air Rescue 10-Yard Fight Airwolf 18 Holes Pro Golf Ajax 1941: Counter Attack Aladdin 1942 Alcon 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars 1943: The Battle of Midway Ali Baba and 40 Thieves 1944: The Loop Master Alien Arena 1945k III Alien Challenge 19XX: The War Against Destiny Alien Crush 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge Alien Sector 2020 Super Baseball Alien Storm 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex Alien Syndrome 3-D Bowling Alien vs. Predator 4 En Raya Alien3: The Gun 4 Fun in 1 Aliens 4-D Warriors All American Football 64th. Street - A Detective Story Alley Master 7 Ordi Alligator Hunt 720 Degrees Alpha Fighter / Head On 800 Fathoms Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 88 Games Alpine Racer 99: The Last War Alpine Racer 2 9-Ball Shootout Alpine Ski A Question of Sport Altair A. D. 2083 Altered Beast A.B. Cop Amazing Maze Ace Ambush Ace Attacker American Horseshoes Ace Driver: Racing Evolution American Speedway Ace Driver: Victory Lap AmeriDarts Acrobat Mission Amidar Acrobatic Dog-Fight Andro Dunos Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon Angel Kids Action Fighter Anteater Action Hollywood Apache 3 Aero Fighters APB - All Points Bulletin Aero Fighters 2 / Sonic Wings 2 Appoooh Aero Fighters 3 / Sonic Wings 3 Aqua Jack Aero Fighters Special Aqua Jet After Burner Aqua Rush After Burner II Aquarium Age Of Heroes - Silkroad 2 Arabian Agent Super Bond Arabian Fight Aggressors of Dark Kombat Arabian Magic Ah Eikou no Koshien Arcade Classics Air Attack Arch Rivals Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Area 51 My Games Room Arcade Games Ultra Edition Games List Area 51 / Maximum Force Duo v2.0 Azurian Attack Argus B.C. -

Liste Des Jeux Pour La Console Retro Gameboy 8.983 Jeux

Liste des jeux pour la console Retro Gameboy 8.983 jeux www.2players.shop Table des matières Arcade – 2242 jeux.................................................................................................................................. 3 Atari 7800 – 58 jeux .............................................................................................................................. 56 Game Gear – 332 jeux ........................................................................................................................... 58 Game Gear Hacked – 7 jeux .................................................................................................................. 66 Game Boy – 842 jeux ............................................................................................................................ 67 Game Boy Hacked – 18 jeux.................................................................................................................. 87 Game Boy Advance – 1066 jeux ............................................................................................................ 88 Game Boy Advance Hacked – 21 jeux ................................................................................................. 113 Game Boy Color – 535 jeux ................................................................................................................. 114 Lynx – 84 jeux ...................................................................................................................................... 127 Master -

Arcade Game 100 in 1 List Gba 900 in 1 List A001

Arcade Game 100 in 1 List Gba 900 in 1 List A001 Metal Slug3 G001 Super Mario Advance A002 Metal Slug5 G002 Mario Kart - Super Circui A003 Metal Slug4 G003 Sonic the Hedgehog - Genesis A004 King Of Fighter 2002 G004 Rayman Advance A005 Metal Slug X G005 Pac-Man Collection A006 Vampire Hunter 2 G006 Killer 3D Pool A007 Street Fighter Alpha 3 G007 Konami Krazy Racers A008 Marvel Super Heroes VS Street Fighter G008 Galidor - Defenders of the Outer Dimension A009 Waku Waku 7 G009 Gumby vs. the Astrobots A010 Shocktro G010 Super Monkey Ball Jr A011 King Of Fighter 95 G011 Paperboy - Rampage A012 Mars Matrix G012 Kim Possible - Revenge of Monkey Fist A013 Ninja Master's G013 Legend of Zelda, The - A Link to the Past & Four Swords A014 X-Men G014 Medal of Honor - Underground A015 1944 G015 Zapper A016 Darkstalkers G016 Turok Evolution A017 Armored Warriors G017 BattleBots - Beyond the BattleBox A018 Samurai Shodown II G018 March of the Penguins A019 Bang Bead G019 Sitting Ducks A020 Nightmare in the Dark G020 Need for Speed - Porsche Unleashed A021 King Of Fighter 96 G021 Jimmy Neutron - Boy Genius A022 Zupapa G022 Sega Arcade Gallery A023 Dungeos And Dragons Tower Of Doom G023 Super Bubble Pop A024 Metal Slug 2 G024 Digimon - Battle Spirit A025 Super GEM Fighter Mini Mix G025 Defender A026 Darkstalkers G026 Wings A027 Profgear G027 Tom and Jerry in Infurnal Escape A028 Street Fighter Alpha 2 G028 Megaman & Bass A029 Breaker's G029 Sega Rally Championship A030 Ring Of Destruction G030 Casper A031 Metal Slug G031 Superman - Countdown to Apokolips -

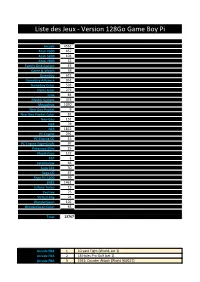

Liste Des Jeux - Version 128Go Game Boy Pi

Liste des Jeux - Version 128Go Game Boy Pi Arcade 4562 Atari 2600 457 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 52 Family Disk System 43 Game & Watch 58 Gameboy 621 Gameboy Advance 951 Gameboy Color 502 Game Gear 277 Lynx 84 Master System 373 Megadrive 1030 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo 152 N64 78 NES 1822 PC-Engine 291 PC-Engine CD 15 PC-Engine SuperGrafx 97 Pokemon Mini 25 Playstation 122 PSP 2 Satellaview 66 Sega 32X 30 Sega CD 47 Sega SG-1000 59 SNES 1461 Sufami Turbo 15 Vectrex 75 Virtual Boy 24 WonderSwan 102 WonderSwan Color 83 Total 13767 Arcade FBA 1 10-yard Fight (World, set 1) Arcade FBA 2 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) Arcade FBA 3 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) Arcade FBA 4 1942 (Revision B) Arcade FBA 5 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) Arcade FBA 6 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) Arcade FBA 7 1943: The Battle of Midway Mark II (US) Arcade FBA 8 1943mii Arcade FBA 9 1944 : The Loop Master (USA 000620) Arcade FBA 10 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) Arcade FBA 11 1945k III Arcade FBA 12 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) Arcade FBA 13 19XX : The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Arcade FBA 14 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Arcade FBA 15 2020 Super Baseball Arcade FBA 16 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) Arcade FBA 17 3 Count Bout Arcade FBA 18 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) Arcade FBA 19 3x3 Puzzle (Enterprise) Arcade FBA 20 4 En Raya (set 1) Arcade FBA 21 4 Fun In 1 Arcade FBA 22 4-D Warriors (315-5162) Arcade FBA 23 4play Arcade FBA 24 64th. -

Sonic the Hedgehog Sonic the Hedgehog 2 Sonic the Hedgehog Sonic the Hedgehog 2 Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine Sonic the Hedge

DREAMCAST Sonic Adventure Sonic Shuffle Sonic Adventure 2 Sega Smash Pack Vol. 1 (Sonic 1) GAME BOY ADVANCE Sega Smash Pack (Sonic Spinball) SEGA MASTER SYSTEM Sonic Advance Sonic the Hedgehog Sonic Advance 2 Sonic the Hedgehog 2 Sonic Pinball Party Sonic Battle GENESIS Sonic the Hedgehog GAMECUBE Sonic the Hedgehog 2 Sonic Adventure 2: Battle Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine Sonic Mega Collection Sonic the Hedgehog Spinball Sonic Adventure DX: Director's Cut Sonic the Hedgehog 3 Sonic Heroes Sonic & Knuckles Sonic 3D Blast REALONE ARCADE Sonic Classics Sonic the Hedgehog Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine GAME GEAR Sonic the Hedgehog 2 Sonic the Hedgehog Sonic the Hedgehog 3 Sonic the Hedgehog 2 Sonic & Knuckles Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine Sonic Spinball Sonic Spinball Sonic 3D Blast Sonic the Hedgehog Triple Trouble Sonic Drift 2 PALM HANDHELD DEVICES Sonic Labyrinth Sonic the Hedgehog Tails Adventures Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine Sonic Blast PLAYSTATION 2 SATURN Sonic Heroes Sonic 3D Blast Sonic Jam XBO X Sonic R Sonic Heroes SEGA PC OTHER Sonic the Hedgehog CD ARCADE Sonic Schoolhouse Sonic Championship Sonic R SegaSonic the Hedgehog Sonic and Garfield Pack SEGA CD Sonic & Knuckles Collection Sonic the Hedgehog CD Sega PC Puzzle Pack (Dr. Robotnik's) PICO Sega Smash Pack (Sonic Spinball) Sonic the Hedgehog's Gameworld Sega Smash Pack 2 (Sonic 2) Tails & the Music Maker Sonic Action Pack SEGA 32X Twin Pack Knuckles' Chaotix NEOGEO POCKET COLOR SYSTEM Sonic the Hedgehog Pocket Adventure. -

Game Boy Advance

List of Game Boy Advance Games 1) 007: Everything or Nothing 28) Boktai 2: Solar Boy Django 2) 007: NightFire 29) Boktai 3: Sabata's Counterattack 3) Advance Guardian Heroes 30) Boktai: The Sun Is in Your Hand 4) Advance Wars 31) Bomberman Max 2 Red Advance 5) Advance Wars 2: Black Hole Rising 32) Bomberman Max 2: Blue Advance 6) Aero the Acrobat 33) Bomberman Tournament 7) AirForce Delta Storm 34) Breath of Fire 8) Alien Hominid 35) Breath of Fire II 9) Alienators: Evolution Continues 36) Broken Circle 10) Altered Beast: Guardian of the Realms 37) Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars 11) Anguna - Warriors of Virtue 38) Bruce Lee: Return of the Legend 12) Another World 39) Bubble Bobble: Old & New 13) Astro Boy: Omega Factor 40) CIMA: The Enemy 14) BackTrack 41) CT Special Forces 15) Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance 42) CT Special Forces 2: Back in the Trenches 16) Banjo-Kazooie: Grunty's Revenge 43) CT Special Forces 3: Navy Ops 17) Banjo-Pilot 44) Caesars Palace Advance: Millenium Gold 18) Baseball Advance Edition 19) Batman Begins 45) Car Battler Joe 20) Batman: Rise of Sin Tzu 46) Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow 21) Batman: Vengeance 47) Castlevania: Circle of the Moon 22) Battle B-Daman 48) Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance 23) Battle B-Daman: Fire Spirits! 49) ChuChu Rocket! 24) Beyblade: G-Revolution 50) Classic NES Series: Dr. Mario 25) Black Matrix Zero 51) Classic NES Series: Super Mario Bros. 26) Blackthorne 52) Columns Crown 27) Blades of Thunder 53) Comix Zone 79) Disney's Magical Quest 3 Starring Mickey & Donald 54) Contra