Algebra I Cheat Sheet Axioms of Equality Solving Equations Solving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solving Cubic Polynomials

Solving Cubic Polynomials 1.1 The general solution to the quadratic equation There are four steps to finding the zeroes of a quadratic polynomial. 1. First divide by the leading term, making the polynomial monic. a 2. Then, given x2 + a x + a , substitute x = y − 1 to obtain an equation without the linear term. 1 0 2 (This is the \depressed" equation.) 3. Solve then for y as a square root. (Remember to use both signs of the square root.) a 4. Once this is done, recover x using the fact that x = y − 1 . 2 For example, let's solve 2x2 + 7x − 15 = 0: First, we divide both sides by 2 to create an equation with leading term equal to one: 7 15 x2 + x − = 0: 2 2 a 7 Then replace x by x = y − 1 = y − to obtain: 2 4 169 y2 = 16 Solve for y: 13 13 y = or − 4 4 Then, solving back for x, we have 3 x = or − 5: 2 This method is equivalent to \completing the square" and is the steps taken in developing the much- memorized quadratic formula. For example, if the original equation is our \high school quadratic" ax2 + bx + c = 0 then the first step creates the equation b c x2 + x + = 0: a a b We then write x = y − and obtain, after simplifying, 2a b2 − 4ac y2 − = 0 4a2 so that p b2 − 4ac y = ± 2a and so p b b2 − 4ac x = − ± : 2a 2a 1 The solutions to this quadratic depend heavily on the value of b2 − 4ac. -

A Review of Some Basic Mathematical Concepts and Differential Calculus

A Review of Some Basic Mathematical Concepts and Differential Calculus Kevin Quinn Assistant Professor Department of Political Science and The Center for Statistics and the Social Sciences Box 354320, Padelford Hall University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-4320 October 11, 2002 1 Introduction These notes are written to give students in CSSS/SOC/STAT 536 a quick review of some of the basic mathematical concepts they will come across during this course. These notes are not meant to be comprehensive but rather to be a succinct treatment of some of the key ideas. The notes draw heavily from Apostol (1967) and Simon and Blume (1994). Students looking for a more detailed presentation are advised to see either of these sources. 2 Preliminaries 2.1 Notation 1 1 R or equivalently R denotes the real number line. R is sometimes referred to as 1-dimensional 2 Euclidean space. 2-dimensional Euclidean space is represented by R , 3-dimensional space is rep- 3 k resented by R , and more generally, k-dimensional Euclidean space is represented by R . 1 1 Suppose a ∈ R and b ∈ R with a < b. 1 A closed interval [a, b] is the subset of R whose elements are greater than or equal to a and less than or equal to b. 1 An open interval (a, b) is the subset of R whose elements are greater than a and less than b. 1 A half open interval [a, b) is the subset of R whose elements are greater than or equal to a and less than b. -

Factoring Polynomials

EAP/GWL Rev. 1/2011 Page 1 of 5 Factoring a polynomial is the process of writing it as the product of two or more polynomial factors. Example: — Set the factors of a polynomial equation (as opposed to an expression) equal to zero in order to solve for a variable: Example: To solve ,; , The flowchart below illustrates a sequence of steps for factoring polynomials. First, always factor out the Greatest Common Factor (GCF), if one exists. Is the equation a Binomial or a Trinomial? 1 Prime polynomials cannot be factored Yes No using integers alone. The Sum of Squares and the Four or more quadratic factors Special Cases? terms of the Sum and Difference of Binomial Trinomial Squares are (two terms) (three terms) Factor by Grouping: always Prime. 1. Group the terms with common factors and factor 1. Difference of Squares: out the GCF from each Perfe ct Square grouping. 1 , 3 Trinomial: 2. Sum of Squares: 1. 2. Continue factoring—by looking for Special Cases, 1 , 2 2. 3. Difference of Cubes: Grouping, etc.—until the 3 equation is in simplest form FYI: A Sum of Squares can 1 , 2 (or all factors are Prime). 4. Sum of Cubes: be factored using imaginary numbers if you rewrite it as a Difference of Squares: — 2 Use S.O.A.P to No Special √1 √1 Cases remember the signs for the factors of the 4 Completing the Square and the Quadratic Formula Sum and Difference Choose: of Cubes: are primarily methods for solving equations rather 1. Factor by Grouping than simply factoring expressions. -

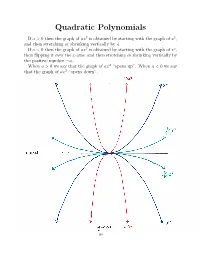

Quadratic Polynomials

Quadratic Polynomials If a>0thenthegraphofax2 is obtained by starting with the graph of x2, and then stretching or shrinking vertically by a. If a<0thenthegraphofax2 is obtained by starting with the graph of x2, then flipping it over the x-axis, and then stretching or shrinking vertically by the positive number a. When a>0wesaythatthegraphof− ax2 “opens up”. When a<0wesay that the graph of ax2 “opens down”. I Cit i-a x-ax~S ~12 *************‘s-aXiS —10.? 148 2 If a, c, d and a = 0, then the graph of a(x + c) 2 + d is obtained by If a, c, d R and a = 0, then the graph of a(x + c)2 + d is obtained by 2 R 6 2 shiftingIf a, c, the d ⇥ graphR and ofaax=⇤ 2 0,horizontally then the graph by c, and of a vertically(x + c) + byd dis. obtained (Remember by shiftingshifting the the⇥ graph graph of of axax⇤ 2 horizontallyhorizontally by by cc,, and and vertically vertically by by dd.. (Remember (Remember thatthatd>d>0meansmovingup,0meansmovingup,d<d<0meansmovingdown,0meansmovingdown,c>c>0meansmoving0meansmoving thatleft,andd>c<0meansmovingup,0meansmovingd<right0meansmovingdown,.) c>0meansmoving leftleft,and,andc<c<0meansmoving0meansmovingrightright.).) 2 If a =0,thegraphofafunctionf(x)=a(x + c) 2+ d is called a parabola. If a =0,thegraphofafunctionf(x)=a(x + c)2 + d is called a parabola. 6 2 TheIf a point=0,thegraphofafunction⇤ ( c, d) 2 is called thefvertex(x)=aof(x the+ c parabola.) + d is called a parabola. The point⇤ ( c, d) R2 is called the vertex of the parabola. -

The Quadratic Formula You May Recall the Quadratic Formula for Roots of Quadratic Polynomials Ax2 + Bx + C

For example, when we take the polynomial f (x) = x2 − 3x − 4, we obtain p 3 ± 9 + 16 2 which gives 4 and −1. Some quick terminology 2 I We say that 4 and −1 are roots of the polynomial x − 3x − 4 or solutions to the polynomial equation x2 − 3x − 4 = 0. 2 I We may factor x − 3x − 4 as (x − 4)(x + 1). 2 I If we denote x − 3x − 4 as f (x), we have f (4) = 0 and f (−1) = 0. The quadratic formula You may recall the quadratic formula for roots of quadratic polynomials ax2 + bx + c. It says that the solutions to this polynomial are p −b ± b2 − 4ac : 2a Some quick terminology 2 I We say that 4 and −1 are roots of the polynomial x − 3x − 4 or solutions to the polynomial equation x2 − 3x − 4 = 0. 2 I We may factor x − 3x − 4 as (x − 4)(x + 1). 2 I If we denote x − 3x − 4 as f (x), we have f (4) = 0 and f (−1) = 0. The quadratic formula You may recall the quadratic formula for roots of quadratic polynomials ax2 + bx + c. It says that the solutions to this polynomial are p −b ± b2 − 4ac : 2a For example, when we take the polynomial f (x) = x2 − 3x − 4, we obtain p 3 ± 9 + 16 2 which gives 4 and −1. 2 I We may factor x − 3x − 4 as (x − 4)(x + 1). 2 I If we denote x − 3x − 4 as f (x), we have f (4) = 0 and f (−1) = 0. -

Linear Gaps Between Degrees for the Polynomial Calculus Modulo Distinct Primes

Linear Gaps Between Degrees for the Polynomial Calculus Modulo Distinct Primes Sam Buss1;2 Dima Grigoriev Department of Mathematics Computer Science and Engineering Univ. of Calif., San Diego Pennsylvania State University La Jolla, CA 92093-0112 University Park, PA 16802-6106 [email protected] [email protected] Russell Impagliazzo1;3 Toniann Pitassi1;4 Computer Science and Engineering Computer Science Univ. of Calif., San Diego University of Arizona La Jolla, CA 92093-0114 Tucson, AZ 85721-0077 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract e±cient search algorithms and in part by the desire to extend lower bounds on proposition proof complexity This paper gives nearly optimal lower bounds on the to stronger proof systems. minimum degree of polynomial calculus refutations of The Nullstellensatz proof system is a propositional Tseitin's graph tautologies and the mod p counting proof system based on Hilbert's Nullstellensatz and principles, p 2. The lower bounds apply to the was introduced in [1]. The polynomial calculus (PC) ¸ polynomial calculus over ¯elds or rings. These are is a stronger propositional proof system introduced the ¯rst linear lower bounds for polynomial calculus; ¯rst by [4]. (See [8] and [3] for subsequent, more moreover, they distinguish linearly between proofs over general treatments of algebraic proof systems.) In the ¯elds of characteristic q and r, q = r, and more polynomial calculus, one begins with an initial set of 6 generally distinguish linearly the rings Zq and Zr where polynomials and the goal is to prove that they cannot q and r do not have the identical prime factors. -

Nature of the Discriminant

Name: ___________________________ Date: ___________ Class Period: _____ Nature of the Discriminant Quadratic − b b 2 − 4ac x = b2 − 4ac Discriminant Formula 2a The discriminant predicts the “nature of the roots of a quadratic equation given that a, b, and c are rational numbers. It tells you the number of real roots/x-intercepts associated with a quadratic function. Value of the Example showing nature of roots of Graph indicating x-intercepts Discriminant b2 – 4ac ax2 + bx + c = 0 for y = ax2 + bx + c POSITIVE Not a perfect x2 – 2x – 7 = 0 2 b – 4ac > 0 square − (−2) (−2)2 − 4(1)(−7) x = 2(1) 2 32 2 4 2 x = = = 1 2 2 2 2 Discriminant: 32 There are two real roots. These roots are irrational. There are two x-intercepts. Perfect square x2 + 6x + 5 = 0 − 6 62 − 4(1)(5) x = 2(1) − 6 16 − 6 4 x = = = −1,−5 2 2 Discriminant: 16 There are two real roots. These roots are rational. There are two x-intercepts. ZERO b2 – 4ac = 0 x2 – 2x + 1 = 0 − (−2) (−2)2 − 4(1)(1) x = 2(1) 2 0 2 x = = = 1 2 2 Discriminant: 0 There is one real root (with a multiplicity of 2). This root is rational. There is one x-intercept. NEGATIVE b2 – 4ac < 0 x2 – 3x + 10 = 0 − (−3) (−3)2 − 4(1)(10) x = 2(1) 3 − 31 3 31 x = = i 2 2 2 Discriminant: -31 There are two complex/imaginary roots. There are no x-intercepts. Quadratic Formula and Discriminant Practice 1. -

Formula Sheet 1 Factoring Formulas 2 Exponentiation Rules

Formula Sheet 1 Factoring Formulas For any real numbers a and b, (a + b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2 Square of a Sum (a − b)2 = a2 − 2ab + b2 Square of a Difference a2 − b2 = (a − b)(a + b) Difference of Squares a3 − b3 = (a − b)(a2 + ab + b2) Difference of Cubes a3 + b3 = (a + b)(a2 − ab + b2) Sum of Cubes 2 Exponentiation Rules p r For any real numbers a and b, and any rational numbers and , q s ap=qar=s = ap=q+r=s Product Rule ps+qr = a qs ap=q = ap=q−r=s Quotient Rule ar=s ps−qr = a qs (ap=q)r=s = apr=qs Power of a Power Rule (ab)p=q = ap=qbp=q Power of a Product Rule ap=q ap=q = Power of a Quotient Rule b bp=q a0 = 1 Zero Exponent 1 a−p=q = Negative Exponents ap=q 1 = ap=q Negative Exponents a−p=q Remember, there are different notations: p q a = a1=q p q ap = ap=q = (a1=q)p 1 3 Quadratic Formula Finally, the quadratic formula: if a, b and c are real numbers, then the quadratic polynomial equation ax2 + bx + c = 0 (3.1) has (either one or two) solutions p −b ± b2 − 4ac x = (3.2) 2a 4 Points and Lines Given two points in the plane, P = (x1; y1);Q = (x2; y2) you can obtain the following information: p 2 2 1. The distance between them, d(P; Q) = (x2 − x1) + (y2 − y1) . x + x y + y 2. -

(Trying To) Solve Higher Order Polynomial Equations. Featuring a Recall of Polynomial Long Division

(Trying to) solve Higher order polynomial equations. Featuring a recall of polynomial long division. Some history: The quadratic formula (Dating back to antiquity) allows us to solve any quadratic equation. ax2 + bx + c = 0 What about any cubic equation? ax3 + bx2 + cx + d = 0? In the 1540's Cardano produced a \cubic formula." It is too complicated to actually write down here. See today's extra credit. What about any quartic equation? ax4 + bx3 + cx2 + dx + e = 0? A few decades after Cardano, Ferrari produced a \quartic formula" More complicated still than the cubic formula. In the 1820's Galois (age ∼19) proved that there is no general algebraic formula for the solutions to a degree 5 polynomial. In fact there is no purely algebraic way to solve x5 − x − 1 = 0: Galois died in a duel at age 21. This means that, as disheartening as it may feel, we will never get a formulaic solution to a general polynomial equation. The best we can get is tricks that work sometimes. Think of these tricks as analogous to the strategies you use to factor a degree 2 polynomial. Trick 1 If you find one solution, then you can find a factor and reduce to a simpler polynomial equation. Example. 2x2 − x2 − 1 = 0 has x = 1 as a solution. This means that x − 1 MUST divide 2x3 − x2 − 1. Use polynomial long division to write 2x3 − x2 − 1 as (x − 1) · (something). Now find the remaining two roots 1 2 For you: Find all of the solutions to x3 + x2 + x + 1 = 0 given that x = −1 is a solution to this equation. -

Gröbner Bases Tutorial

Gröbner Bases Tutorial David A. Cox Gröbner Basics Gröbner Bases Tutorial Notation and Definitions Gröbner Bases Part I: Gröbner Bases and the Geometry of Elimination The Consistency and Finiteness Theorems Elimination Theory The Elimination Theorem David A. Cox The Extension and Closure Theorems Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Prove Extension and Amherst College Closure ¡ ¢ £ ¢ ¤ ¥ ¡ ¦ § ¨ © ¤ ¥ ¨ Theorems The Extension Theorem ISSAC 2007 Tutorial The Closure Theorem An Example Constructible Sets References Outline Gröbner Bases Tutorial 1 Gröbner Basics David A. Cox Notation and Definitions Gröbner Gröbner Bases Basics Notation and The Consistency and Finiteness Theorems Definitions Gröbner Bases The Consistency and 2 Finiteness Theorems Elimination Theory Elimination The Elimination Theorem Theory The Elimination The Extension and Closure Theorems Theorem The Extension and Closure Theorems 3 Prove Extension and Closure Theorems Prove The Extension Theorem Extension and Closure The Closure Theorem Theorems The Extension Theorem An Example The Closure Theorem Constructible Sets An Example Constructible Sets 4 References References Begin Gröbner Basics Gröbner Bases Tutorial David A. Cox k – field (often algebraically closed) Gröbner α α α Basics x = x 1 x n – monomial in x ,...,x Notation and 1 n 1 n Definitions α ··· Gröbner Bases c x , c k – term in x1,...,xn The Consistency and Finiteness Theorems ∈ k[x]= k[x1,...,xn] – polynomial ring in n variables Elimination Theory An = An(k) – n-dimensional affine space over k The Elimination Theorem n The Extension and V(I)= V(f1,...,fs) A – variety of I = f1,...,fs Closure Theorems ⊆ nh i Prove I(V ) k[x] – ideal of the variety V A Extension and ⊆ ⊆ Closure √I = f k[x] m f m I – the radical of I Theorems { ∈ |∃ ∈ } The Extension Theorem The Closure Theorem Recall that I is a radical ideal if I = √I. -

Monomial Orderings, Rewriting Systems, and Gröbner Bases for The

Monomial orderings, rewriting systems, and Gr¨obner bases for the commutator ideal of a free algebra Susan M. Hermiller Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68588 [email protected] Xenia H. Kramer Department of Mathematics Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] Reinhard C. Laubenbacher Department of Mathematics New Mexico State University Las Cruces, NM 88003 [email protected] 0Key words and phrases. non-commutative Gr¨obner bases, rewriting systems, term orderings. 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. 13P10, 16D70, 20M05, 68Q42 The authors thank Derek Holt for helpful suggestions. The first author also wishes to thank the National Science Foundation for partial support. 1 Abstract In this paper we consider a free associative algebra on three gen- erators over an arbitrary field K. Given a term ordering on the com- mutative polynomial ring on three variables over K, we construct un- countably many liftings of this term ordering to a monomial ordering on the free associative algebra. These monomial orderings are total well orderings on the set of monomials, resulting in a set of normal forms. Then we show that the commutator ideal has an infinite re- duced Gr¨obner basis with respect to these monomial orderings, and all initial ideals are distinct. Hence, the commutator ideal has at least uncountably many distinct reduced Gr¨obner bases. A Gr¨obner basis of the commutator ideal corresponds to a complete rewriting system for the free commutative monoid on three generators; our result also shows that this monoid has at least uncountably many distinct mini- mal complete rewriting systems. -

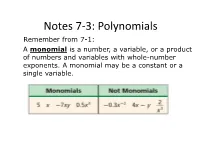

Polynomials Remember from 7-1: a Monomial Is a Number, a Variable, Or a Product of Numbers and Variables with Whole-Number Exponents

Notes 7-3: Polynomials Remember from 7-1: A monomial is a number, a variable, or a product of numbers and variables with whole-number exponents. A monomial may be a constant or a single variable. I. Identifying Polynomials A polynomial is a monomial or a sum or difference of monomials. Some polynomials have special names. A binomial is the sum of two monomials. A trinomial is the sum of three monomials. • Example: State whether the expression is a polynomial. If it is a polynomial, identify it as a monomial, binomial, or trinomial. Expression Polynomial? Monomial, Binomial, or Trinomial? 2x - 3yz Yes, 2x - 3yz = 2x + (-3yz), the binomial sum of two monomials 8n3+5n-2 No, 5n-2 has a negative None of these exponent, so it is not a monomial -8 Yes, -8 is a real number Monomial 4a2 + 5a + a + 9 Yes, the expression simplifies Monomial to 4a2 + 6a + 9, so it is the sum of three monomials II. Degrees and Leading Coefficients The terms of a polynomial are the monomials that are being added or subtracted. The degree of a polynomial is the degree of the term with the greatest degree. The leading coefficient is the coefficient of the variable with the highest degree. Find the degree and leading coefficient of each polynomial Polynomial Terms Degree Leading Coefficient 5n2 5n 2 2 5 -4x3 + 3x2 + 5 -4x2, 3x2, 3 -4 5 -a4-1 -a4, -1 4 -1 III. Ordering the terms of a polynomial The terms of a polynomial may be written in any order. However, the terms of a polynomial are usually arranged so that the powers of one variable are in descending (decreasing, large to small) order.