Authority, Property and Matriliny Under Colonial Law in Nineteenth Century Malabar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited

Press Release South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited February 11, 2021 Ratings Amount Facilities Rating1 Rating Action (Rs. crore) Revised from CARE BB; CARE BB-; Stable; Stable (Double B; Outlook: ISSUER NOT COOPERATING* Long -term Bank Facilities 7.52 Stable) and moved to (Double B Minus; Outlook: Stable; ISSUER NOT COOPERATING ISSUER NOT COOPERATING*) category CARE A4; Rating moved to ISSUER ISSUER NOT COOPERATING* NOT COOPERATING Short-term Bank Facilities 1.50 (A Four; category ISSUER NOT COOPERATING*) 9.02 Total Facilities (Rs. Nine Crores and Two Lakhs Only) Details of facilities in Annexure-1 *Based on best available information Detailed Rationale & Key Rating Drivers CARE has been seeking information, to carry out annual surveillance, from South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited (SMSAPL) to monitor the rating(s) vide e-mail communications dated January 14, 2021, January 21, 2021, January 25, 2021, January 27, 2021 and numerous phone calls. However despite our repeated requests, the company has not provided the information for monitoring the requisite ratings. In line with the extant SEBI guidelines, CARE has reviewed the rating on the basis of the best available information which however, in CARE’s opinion is not sufficient to arrive at a fair rating. The rating on South Malabar Steels and Alloys Private Limited bank facilities will now be denoted as CARE BB-; Stable/CARE A4; ISSUER NOT COOPERATING. Further due diligence with the lender and auditor could not be conducted. Users of this rating (including investors, lenders and the public at large) are hence requested to exercise caution while using the above rating. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Malaria Control in South Malabar, Madras State

Bull. Org. mond. Sante | 1954, 11, 679-723 Bull. Wld Hlth Org. MALARIA CONTROL IN SOUTH MALABAR, MADRAS STATE L. MARA, M.D. Senior Adviser and Team-leader, WHO Malaria-Control Demonstration Team, Suleimaniya, Iraq formerly, Senior Adviser and Team-leader, WHO Malaria-Control Demonstration Team, South Malabar Manuscript received in January 1954 SYNOPSIS The author describes the activities and achievements of a two- year malaria-control demonstration-organized by WHO, UNICEF, the Indian Government, and the Government of Madras State- in South Malabar. Widespread insecticidal work, using a dosage of 200 mg of DDT per square foot (2.2 g per m2), protected 52,500 people in 1950, and 115,500 in 1951, at a cost of about Rs 0/13/0 (US$0.16) per capita. The final results showed a considerable decrease in the size of the endemic areas; in the spleen- and parasite-rates of children; and in the number of malaria cases detected by the team or treated in local hospitals and dispensaries. During December 1949 a malaria-control project, undertaken jointly by WHO, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Govern- ment of India, and the Government of Madras State, started operations in the malarious areas among the foothills and tracts of Ernad and Walavanad taluks in South Malabar. During 1951 the operational area was extended to include almost all the malarious parts of Ernad and Walavanad as well as the northernmost part of Palghat taluk (see map 1 a). The staff of the international team provided by WHO consisted of a senior adviser and team-leader and a public-health nurse. -

Key Electoral Data of Taliparamba Assembly Constituency

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-008-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-602-4 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 128 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages -

212-223 HYDROLOGY of the KORAPUZHA ESTUARY, MALABAR, KERALA STATE* Central Marine Fisher

J. Mar. biol. Ass. India, 1959, 1 (2).' 212-223 HYDROLOGY OF THE KORAPUZHA ESTUARY, MALABAR, KERALA STATE* By S. V. SURYANARAYANA RAO & P. C. GEORGE Central Marine Fisheries Research Station, Mandapam Camp INTRODUCTION A preliminary enquiry on the hydrological and planktological conditions in the river mouth region was conducted during the period 1950-52 and the results pub lished in an abstract form (George, 1953a). This study was later extended to cover the 25 km seaward region of the estuary in 1954. As is well known, the Malabar coast is highly productive from the fisheries point of view and it was also observed that the sea waters of the inshore region off Calicut are rich in plank ton and nutrient salts (George, 19536). Results of the present investigation would therefore serve to assess the influence of land drainage in the enrichment and re plenishment of the coastal waters and allied factors. The west coast of India which is subjected to a heavy rainfall amounting to more than 300 cm per annum, is characterised by numerous short and swift rivers which carry the,enormous amounts of the waters from the Western Ghats into the sea. TOPOGRAPHY OF THE ESTUARY The Korapuzha is a short and shallow river, 52 km long and consists of the Elathur River which joins the Korapuzha backwater system close to the mouth of the estuary about a kilometer away from the sea and another stream running from the foot of the high mountain range surrounding the Kodiyanadumalai (700 Metres) which also empties into the back-waters near Kaniangode about 16 km away from the river mouth. -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

Twenty Years of Home-Based Palliative Care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a Descriptive Study of Patients and Their Care-Givers

Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers Authors Philip, RR; Philip, S; Tripathy, JP; Manima, A; Venables, E Citation Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers. 2018, 17 (1):26 BMC Palliat Care DOI 10.1186/s12904-018-0278-4 Publisher BioMed Central Journal BMC Palliative Care Rights Archived with thanks to BMC Palliative Care Download date 03/10/2021 01:36:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10144/619144 Philip et al. BMC Palliative Care (2018) 17:26 DOI 10.1186/s12904-018-0278-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers Rekha Rachel Philip1*, Sairu Philip1, Jaya Prasad Tripathy2, Abdulla Manima3 and Emilie Venables4,5 Abstract Background: The well lauded community-based palliative care programme of Kerala, India provides medical and social support, through home-based care, for patients with terminal illness and diseases requiring long-term support. There is, however, limited information on patient characteristics, caregivers and programme performance. This study was carried out to describe: i) the patients enrolled in the programme from 1996 to 2016 and their diagnosis, and ii) the care-giver characteristics and palliative care support from nurses and doctors in a cohort of patients registered during 2013–2015. Methods: A descriptive study was conducted in the oldest community-based palliative clinic in Kerala. Data were collected from annual patient registers from 1996 to 2016 and patient case records during the period 2013–2015. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kannur District from 15.12.2019To21.12.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Kannur district from 15.12.2019to21.12.2019 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 544/2019 U/s Kayaplackkal house 21-12- Suneeshkuma 21, 279 IPC&3(1) Kannavam Prasobh K.K SI BAILED BY 1 Sujith Suresh cumbummettu Po Edayar. 2019 at r Male r/w 181 of MV (KANNUR) of Police POLICE parakkada 20:48 Hrs act 21-12- 989/2019 U/s mp azad 31, mulloli house Kuthuparamb BAILED BY 2 sajith mohanan kuthuparamba 2019 at 15(c) r/w 63 of inspetor of Male manantheri a (KANNUR) POLICE 21:00 Hrs Abkari Act police 21-12- 988/2019 U/s kunnikkanna 36, ithikkandy gov hospital Kuthuparamb Raju K si of BAILED BY 3 Rijith ek 2019 at 279,IPC &185 n Male house,erammala kuthuparamba a (KANNUR) police POLICE 20:05 Hrs of mv act THEKKE THALAKKAL HOUSE Nr NEW BUS 21-12- 1229/2019 SI OF POLICE VISWANADHA 50, Payyannur BAILED BY 4 GOPALAN KADANNAPPALLI STAND 2019 at U/s 118(a) of BALAKRISHNA N.T.T Male (KANNUR) POLICE AMSOM PAYYANNUR 19:35 Hrs KP Act N .C CHANTHAPPURA Kadambur 21-12- 623/2019 U/s 50, Rajasree sadanam amsom Edakkad Sheeju TK, SI BAILED BY 5 Rajesh K Krishnan Nair 2019 at 15(c) r/w 63 of Male Kadambur Edakkad Kadachira (KANNUR) of Police POLICE 18:30 Hrs Abkari Act doctor mukku 408/2019 U/s Illimoottil house, 21-12- 41, 188,283 IPC & Cherupuzha BAILED BY 6 Shibu Jose Jose Pulingome amsom, -

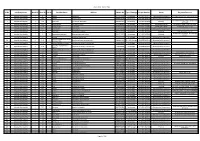

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

A CONCISE REPORT on BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE to 2018 FLOOD in KERALA (Impact Assessment Conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board)

1 A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) Editors Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.), Dr. V. Balakrishnan, Dr. N. Preetha Editorial Board Dr. K. Satheeshkumar Sri. K.V. Govindan Dr. K.T. Chandramohanan Dr. T.S. Swapna Sri. A.K. Dharni IFS © Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, tramsmitted in any form or by any means graphics, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior writted permission of the publisher. Published By Member Secretary Kerala State Biodiversity Board ISBN: 978-81-934231-3-4 Design and Layout Dr. Baijulal B A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) EdItorS Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.) Dr. V. Balakrishnan Dr. N. Preetha Kerala State Biodiversity Board No.30 (3)/Press/CMO/2020. 06th January, 2020. MESSAGE The Kerala State Biodiversity Board in association with the Biodiversity Management Committees - which exist in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporations in the State - had conducted a rapid Impact Assessment of floods and landslides on the State’s biodiversity, following the natural disaster of 2018. This assessment has laid the foundation for a recovery and ecosystem based rejuvenation process at the local level. Subsequently, as a follow up, Universities and R&D institutions have conducted 28 studies on areas requiring attention, with an emphasis on riverine rejuvenation. I am happy to note that a compilation of the key outcomes are being published. -

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families. -

The Ascent of 'Kerala Model' of Public Health

THE ASCENT OF ‘KERALA MODEL’ OF PUBLIC HEALTH CC. Kartha Kerala Institute of Medical Sciences, Trivandrum, Kerala [email protected] Kerala, a state on the southwestern Coast of India is the best performer in the health sector in the country according to the health index of NITI Aayog, a policy think-tank of the Government of India. Their index, based on 23 indicators such as health outcomes, governance and information, and key inputs and processes, with each domain assigned a weight based on its importance. Clearly, this outcome is the result of investments and strategies of successive governments, in public health care over more than two centuries. The state of Kerala was formed on 1 November 1956, by merging Malayalam-speaking regions of the former states of Travancore-Cochin and Madras. The remarkable progress made by Kerala, particularly in the field of education, health and social transformation is not a phenomenon exclusively post 1956. Even during the pre-independence period, the Travancore, Cochin and Malabar provinces, which merged to give birth to Kerala, have contributed substantially to the overall development of the state. However, these positive changes were mostly confined to the erstwhile princely states of Travancore and Cochin, which covered most of modern day central and southern Kerala. The colonial policies, which isolated British Malabar from Travancore and Cochin, as well as several social and cultural factors adversely affected the general and health care infrastructure developments in the colonial Malabar region. Compared to Madras Presidency, Travancore seems to have paid greater attention to the health of its people. Providing charity to its people through medical relief was regarded as one of the main functions of the state.