Update on Electric Vehicle Adoption Across U.S. Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, and REPOWERS

What Fleets Need to Know About Alternative Fuel Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Acknowledgments This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 with Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, the Manager and Operator of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work was made possible through funding provided by National Clean Cities Program Director and DOE Vehicle Technologies Office Deployment Manager Dennis Smith. This publication is part of a series. For other lessons learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) projects, please refer to the following publications: • American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – Clean Cities Project Awards (DOE/GO-102016-4855 - August 2016) • Designing a Successful Transportation Project – Lessons Learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment Projects (DOE/GO-102017-4955 - September 2017) Authors Kay Kelly and John Gonzales, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Disclaimer This document is not intended for use as a “how to” guide for individuals or organizations performing a conversion, repower, or retrofit. Instead, it is intended to be used as a guide and resource document for informational purposes only. VEHICLE TECHNOLOGIES OFFICE | cleancities.energy.gov 2 ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric

Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks∗ Guang Wang Xiuyuan Chen Fan Zhang Rutgers University Rutgers University Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced [email protected] [email protected] Technology, CAS [email protected] Yang Wang Desheng Zhang University of Science and Rutgers University Technology of China [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Due to the ever-growing concerns on the air pollution and • Networks → Network measurement; Mobile networks; energy security, many cities have started to update their Cyber-physical networks. taxi fleets with electric ones. Although environmentally friendly, the rapid promotion of electric taxis raises prob- KEYWORDS lems to both taxi drivers and governments, e.g., prolonged Electric vehicle; mobility pattern; charging pattern; evolving waiting/charging time, unbalanced utilization of charging experience; shared autonomous vehicle infrastructures and reduced taxi supply due to the long charg- ing time. In this paper, we make the first effort to understand ACM Reference Format: the long-term evolving patterns through a five-year study Guang Wang, Xiuyuan Chen, Fan Zhang, Yang Wang, and Desh- on one of the largest electric taxi networks in the world, i.e., eng Zhang. 2019. Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving the Shenzhen electric taxi network in China. In particular, Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks. In The 25th Annual we perform a comprehensive measurement investigation International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (Mo- called ePat to explore the evolving mobility and charging biCom ’19), October 21–25, 2019, Los Cabos, Mexico. ACM, New York, patterns of electric vehicles. -

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles?

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles? Many of us have likely considered an alternative fuel vehicle at some point in our lives. Balancing the positives and negatives is a tricky process and varies greatly based on our personal situations. However, many of the negatives that previously created hesitancy have changed in recent years. Below, we have outlined a few of the most commonly mentioned negatives regarding the two leading alternative fuel vehicle types: Flex Fuel vehicles and Electric/Hybrid vehicles. Then, you can decide for yourself whether one of these vehicle types are practical for you! Cost – How much does the vehicle cost to purchase and operate? Flex Fuel: Flex Fuel vehicles typically cost about the same as a gasoline vehicle.1 For fuel cost, E85 typically costs slightly less than gasoline, however, due to decreased efficiency has a slightly higher cost per mile than gasoline.2 Overall, a Flex Fuel vehicle is likely to be slightly more expensive than a gasoline counterpart. Electric/Hybrid: This situation varies quite a bit depending on where you live. Electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles often cost considerably more than a conventional gasoline vehicle. For example, a plug-in hybrid will cost around $4000-$8000 more than a conventional model.3 However, there are federal rebates and local rebates that can refund thousands of dollars from the purchase price. Electric/Hybrid vehicles also tend to save money on fuel, with the possibility of saving thousands of dollars over the lifetime of the vehicle.4 Whether these rebates and fuel cost savings will eventually account for the higher purchase price can be estimated with comparison tools. -

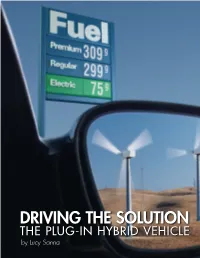

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

A Review of Range Extenders in Battery Electric Vehicles: Current Progress and Future Perspectives

Review A Review of Range Extenders in Battery Electric Vehicles: Current Progress and Future Perspectives Manh-Kien Tran 1,* , Asad Bhatti 2, Reid Vrolyk 1, Derek Wong 1 , Satyam Panchal 2 , Michael Fowler 1 and Roydon Fraser 2 1 Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L3G1, Canada; [email protected] (R.V.); [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (M.F.) 2 Department of Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L3G1, Canada; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (R.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-880-6108 Abstract: Emissions from the transportation sector are significant contributors to climate change and health problems because of the common use of gasoline vehicles. Countries in the world are attempting to transition away from gasoline vehicles and to electric vehicles (EVs), in order to reduce emissions. However, there are several practical limitations with EVs, one of which is the “range anxiety” issue, due to the lack of charging infrastructure, the high cost of long-ranged EVs, and the limited range of affordable EVs. One potential solution to the range anxiety problem is the use of range extenders, to extend the driving range of EVs while optimizing the costs and performance of the vehicles. This paper provides a comprehensive review of different types of EV range extending technologies, including internal combustion engines, free-piston linear generators, fuel cells, micro Citation: Tran, M.-K.; Bhatti, A.; gas turbines, and zinc-air batteries, outlining their definitions, working mechanisms, and some recent Vrolyk, R.; Wong, D.; Panchal, S.; Fowler, M.; Fraser, R. -

Electric Vehicles with a Battery Switching Station: Adoption and Environmental Impact

Electric Vehicles with a Battery Switching Station: Adoption and Environmental Impact _______________ Buket AVCI Karan GIROTRA Serguei NETESSINE 2012/18/TOM Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2005092 Electric Vehicles with a Battery Switching Station: Adoption and Environmental Impact Buket Avci* Karan Girotra** Serguei Netessine*** This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2005092 * PhD Candidate in Technology and Operations Management at INSEAD, Boulevard de Constance 77305 Fontainebleau Cedex, France. Email: [email protected] ** Assistant Professor of Technology and Operations Management at INSEAD, Boulevard de Constance 77305 Fontainebleau Cedex, France. Email: [email protected] *** The Timken Chaired Professor of Global Technology and Innovation, Professor of Technology and Operations Management at INSEAD, Boulevard de Constance 77305 Fontainebleau Cedex, France. Email: [email protected] A Working Paper is the author’s intellectual property. It is intended as a means to promote research to interested readers. Its content should not be copied or hosted on any server without written permission from [email protected] Find more INSEAD papers at http://www.insead.edu/facultyresearch/research/search_papers.cfm Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2005092 ELECTRIC VEHICLES WITH A BATTERY SWITCHING STATION: ADOPTION AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT Abstract. Widespread adoption of Electric Vehicles can limit the environmental impact of trans- portation and reduce oil dependence. However, limited range and high upfront battery costs have limited consumer adoption. A novel switching-station-based solution is extensively touted as a promis- ing remedy that resolves range anxiety. -

Electric Vehicle Adoption: an Analysis of Best Practice and Pitfalls for Policy Making from Experiences of Europe and the US

Received: 4 May 2017 Revised: 17 September 2017 Accepted: 23 November 2017 DOI: 10.1111/gec3.12358 ARTICLE Electric vehicle adoption: An analysis of best practice and pitfalls for policy making from experiences of Europe and the US Gail Helen Broadbent | Danielle Drozdzewski | Graciela Metternicht University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Abstract Correspondence Accelerating the rate of electric vehicle (EV) adoption is an objective Gail Helen Broadbent, University of New of many countries to mitigate and ameliorate negative externalities South Wales. arising from the use of fossil fuels for personal motorised transporta- tion including: greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, air pollution and noise, as well as increasing energy security and reducing budget deficits. Within the dynamic field of EVs, this paper highlights strategic directions for policy makers to increase EV uptake. The paper critically reviews measures adopted by some industrialised countries to motivate consumer purchase of EVs rather than conventional internal combustion vehicles (ICVs). A key focus is the role of financial and soft incentives to encourage EV adoption. The analysis reveals that not all incentives are equally effective; an adequate recharger network appears to be a common concerning factor for EV adoption due to customer anxiety and vehicle limitations. Best practice strategies that could foster a faster transition to EV adoption include appropriate legislation, installation and maintenance of an adequate public recharger network, government procurement programs, and investment in information programs to accelerate the transition towards fossil free driving. The paper evidences how implementation of these strategies can affect overall adoption rates. 1 | INTRODUCTION In 2010, the transport sector contributed 23% of total energy‐related CO2 emissions (UN Climate Summit, 2014), thus making it a driver of climate change as well as agent for responses towards its mitigation. -

EV White Paper

2 | Page UAW Research EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: STRATEGIES FOR A FAIR EV FUTURE .................................................................................. 4 COMING SHIFT TO EVS .................................................................................................................................................... 4 DISRUPTIVE IMPLICATIONS OF EVS ..................................................................................................................................... 4 WILL THE U.S. FALL BEHIND? ........................................................................................................................................... 5 CREATING AN INDUSTRIAL POLICY TO LEAD .......................................................................................................................... 5 WHAT IS AN EV? WHY EVS? ................................................................................................................................... 6 CLIMATE CONCERNS POINT TO EVS .................................................................................................................................... 6 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN EVS AND ICES ............................................................................................................................... 7 THE COMING EV POWERTRAIN DISRUPTION ......................................................................................................... 8 ELECTRIC VEHICLE PRICES TO BECOME COMPETITIVE ............................................................................................................ -

Electric Vehicle Tour Planning Considering Range Anxiety

sustainability Article Electric Vehicle Tour Planning Considering Range Anxiety Rui Chen 1,2 , Xinglu Liu 3, Lixin Miao 2,3 and Peng Yang 2,* 1 Department of Industrial Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] 2 Division of Logistics and Transportation, Graduate School at Shenzhen, Tsinghua University, Shenzhen 518055, China; [email protected] 3 Intelligent Transportation and Logistics Systems Laboratory, Tsinghua-Berkeley Shenzhen Institute, Shenzhen 518055, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23 March 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 2 May 2020 Abstract: In this study, the tour planning problem for electric vehicles is investigated. We aim to derive the optimal route and thus, to maximize profitability and minimize range anxiety within the time horizon. To solve this problem, a bi-objective mixed integer model is proposed. Specifically, we first introduced the reliability of route planning and quantified it as a cost with specific functions. The nonlinear model was then converted into a bi-objective mixed integer linear program, and an interactive branch and bound algorithm was adopted. Numerical experiments conducted on different networks have shown that the model that considers range anxiety offers more effective solutions. This means that our model is able to plan the routes with high reliability and low risk of profit loss and accidents. Keywords: electric vehicle; tour planning; range anxiety; bi-objective programming 1. Introduction Currently, about 86% of global primary energy demand depends on fossil fuels, in which coal, gas and oil account for 23%, 27% and 36%, respectively. Based on current information about reserves and daily production, oil will be depleted in 2066 [1]. -

Calculating Electric Drive Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions

VEHICLE ELECTRIFICatION POLICY STUDY TSA K 5 REPORT AUGUST 2012 © 2012 INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON CLEAN TRANSPORTATION Calculating Electric Drive Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions BY ED PIKE www.theicct.org [email protected] BEIJING | BERLIN | BRUSSELS | SAN FRANCISCO | WASHINGTON The author appreciates the helpful review comments provided by: Kate Blumberg, ICCT Joshua Cunningham, Plug-in Electric Vehicle Collaborative David Ganss, U.S. EPA Pierre Gaudillat John German, ICCT Zoltan Jung, U.S. EPA Li Lili, State Grid Energy Research Institute Alan Lloyd, ICCT Peter Mock, ICCT Ed Nam, U.S. EPA Martin Rocholl, European Climate Foundation Chuck Shulock, Shulock Consulting Luke Tonachel, NRDC Nic Lutsey Michael Wang, Argonne National Laboratory Funding for this work was generously provided by the ClimateWorks Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Energy Foundation. © 2012 The International Council on Clean Transportation 1225 I Street NW, Suite 900, Washington DC 20005 CALCULATING ELECTRIC DRIVE VEHICLE GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The object of this paper is to present a methodology for calculating the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions attributable to the production of electricity and hydrogen used to power electric drive (edrive) vehicles such as battery electric (BEV), plug-in hybrid electric (PHEV), and fuel cell electric (FCEV) vehicles. Calculating these emissions is important for understanding the potential role of edrive vehicles in meeting GHG reduction goals, implementing passenger vehicle GHG standards, and providing consumer information about energy efficiency and emissions. This paper identifies methods ot determine edrive vehicle efficiency, energy supply “well-to-tank” GHG intensity, edrive vehicle miles traveled, and mode split for plug-in hybrids, all of which can serve as a basis for calculating edrive upstream emissions. -

The 'Renewables' Challenge

The ‘Renewables’ Challenge - Biofuels vs. Electric Mobility Hinrich Helms ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Udo Lambrecht ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany Nils Rettenmaier ifeu - Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg, Germany Summary Electric vehicles are considered as a key technology for sustainable transport. The use of biofuels in vehicles with con- ventional combustion engines, however, also offers the possibility for a substantial reduction of greenhouse gas emis- sions, without requiring costly batteries and long charging times and without significantly limiting the driving range. A comparison of environmental impacts between both options needs to be based on a life cycle perspective. First screen- ing results presented in this paper show that a diesel car fuelled with RME has considerably lower climate impacts than a comparable battery electric vehicle charged with average German electricity. On the other hand, the use of RME has disadvantages in other impacts categories such as eutrophication. Battery electric vehicles charged with renewable electricity in turn have the best climate impact balance of the considered options and also show among the lowest im- pacts in eutrophication. However, other biofuels such as palm oil and the use of biomass residues offer further reduc- tion potentials, but possibly face limited resources and land use changes. 1. Introduction man Federal Government has therefore set the target of one million electric vehicles in Germany by 2020. Mobility is an important basis for many economic and On the other hand, the use of biofuels in vehicles with private activities and thus a crucial part of our life.