National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoration of a San Diego Landmark Casa De Bandini, Lot 1, Block 451

1 Restoration of a San Diego Landmark BY VICTOR A. WALSH Casa de Bandini, Lot 1, Block 451, 2600 Calhoun Street, Old Town SHP [California Historical Landmark #72, (1932); listed on National Register of Historic Places (Sept. 3, 1971) as a contributing building] From the far side of the old plaza, the two-story, colonnaded stucco building stands in the soft morning light—a sentinel to history. Originally built 1827-1829 by Don Juan Bandini as a family residence and later converted into a hotel, boarding house, olive pickling factory, and tourist hotel and restaurant, the Casa de Bandini is one of the most significant historic buildings in the state.1 In April 2007, California State Parks and the new concessionaire, Delaware North & Co., embarked on a multi-million dollar rehabilitation and restoration of this historic landmark to return it to its appearance as the Cosmopolitan Hotel of the early 1870s. This is an unprecedented historic restoration, perhaps the most important one currently in progress in California. Few other buildings in the state rival the building’s scale or size (over 10,000 square feet) and blending of 19th-century Mexican adobe and American wood-framing construction techniques. It boasts a rich and storied history—a history that is buried in the material fabric and written and oral accounts left behind by previous generations. The Casa and the Don Bandini would become one of the most prominent men of his day in California. Born and educated in Lima, Peru and the son of a Spanish master trader, he arrived in San Diego around 1822.2 In 1827, Governor José María Echeandia granted him and, José Antonio Estudillo, his future father-in-law, adjoining house lots on the plaza, measuring “…100 varas square (or 277.5 x 277.5’) in common,….”3 Through his marriage to Dolores Estudillo and, after her death in 1833, to Refugio Argüello, the daughter of another influential Spanish Californio family, Bandini carved out an illustrious career as a politician, civic leader, and rancher. -

A Reinvestigation of La Casa De Machado Y Stewart, Old Town State Historic Park, San Diego

A Reinvestigation of La Casa de Machado y Stewart, Old Town State Historic Park, San Diego, California Patrick Scott Geyer, Kristie Anderson, Anna DeYoung, and Jason Richards Overview This article addresses the important role that archaeological field and laboratory techniques play in preserving and restoring an historic San Diego landmark, La Casa de Machado y Stewart. Two separate archaeological excavations were undertaken by two local universities almost thirty-five years apart in an attempt to help the California State Department of Parks and Recreation historically renovate the dilapidated residence and recreate the gardens surrounding it with flora appropriate for the period. The recovery of olive and grape pollen during the latter excavation provided evidence for the continued presence of Spanish and Anglo-American agricultural enterprises in Old Town San Diego. Furthermore, statistically significant amounts of Zea mays (maize) and Phaseolus sp. (bean) pollen suggest the existence of pre-contact Native American agriculture. Background Ever since 74-year old Jose Manuel Machado built it in the 1830s, the Machado-Stewart residence has stood in the area now commonly referred to as Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. In February of 1845, Jack/John Stewart married Jose Manuel Machado’s youngest daughter Rosa and moved into the Machado home. Rosa subsequently gave birth to eleven children in this residence. Descendents of this union continued to live in the single-story adobe dwelling until the final resident, Mrs. Carmen Meza, was forced to leave due to severe damage caused by the rains of 1966 (Ezell and Broadbent 1968). In 1967, an ad-hoc committee acquired the historical adobe and prevented its destruction. -

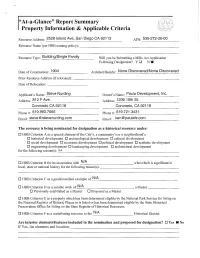

Report Summary Property Information & Applicable Criteria

"At-a-Glance" Report Summary Property Information & Applicable Criteria Resource Address: 2528 Island Ave, San Diego CA 92113 APN: 535-272-26-00 Resource Na111e (per HRB naming policy): ________________________ Resource Type: Building/Single Family Will you be Submitting a Mills Act Application Following Designation? Y □ N Iii Architect/Builder: None Discovered/None Discovered Date of Construction: ---------1 904 Prior Resource Address (ifrelocated): _________________________ Date of Relocation: __________ Applicant's Name: _S_t_e_v_e_N_u_r_d_in_g______ _ Owner's Name: Paula Development, Inc. Address: 812 F Ave. Address: 1206 10th St. Coronado CA 92118 Coronado, CA 92118 Phone#: 619.993.7665 Phone#: 619.721.3431 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The resource is being nominated for designation as a historical resource under: □ HRB Criterion A as a special element of the City's, a community's or a neighborhood's D historical development D archaeological development □ cultural development D social development D economic development D political development D aesthetic development D engineering development D landscaping development D architectural development for the following reason(s): _N_IA___________________________ _ □ HRB Criterion B for its association with _N_/_A___________ who/which is significant in local, state or national history for the following reason(s): -----------~------- D HRB Criterion Casa good/excellent exarhple of _N_/_A__________________ _ □ HRB Criterion Das a notable work of_N_/_A___________ ~ a Master _______ □ Previously established as a Master □ Proposed as a Master D HRB Criterion E as a property which has been determined eligible by the Nation;:tl Park Service for listing on the National Register of Historic Places or is listed or has been determined eligible by the State Historical Preservation Office for listing on the State Register of Historical Resources. -

Historic Context & Survey Report

City of San Diego Old San Diego Community Plan Area Historic Resources Reconnaissance Survey: Historic Context & Survey Report Prepared for: City of San Diego City Planning & Community Investment Department 202 C Street, MS 5A San Diego, CA 92101 Prepared by: Galvin Preservation Associates Inc. 1611 S. Pacific Coast Hwy., Suite 104 Redondo Beach, CA 90277 310.792.2690 * 310.792.2696 (fax) DRAFT Historic Context Statement Introduction The Old San Diego Community Plan Area encompasses approximately 285 acres of relatively flat land that is bounded on the north by Interstate 8 (I-8) and Mission Valley, the west by Interstate 5 (I-5), and on south and east by the Mission Hills/Uptown hillsides. Old San Diego consists of single and multi-family uses (approximately 711 residents), and an abundant variety of tourist-oriented commercial uses (restaurant and drinking establishments, boutiques and specialty shops, jewelry stores, art stores and galleries, crafts shops, and museums). A sizeable portion of Old San Diego consists of dedicated parkland; including Old Town San Diego State Park, Presidio Park (City), Heritage Park (County), and numerous public parking facilities. There are approximately 26 designated historical sites in the Old San Diego Community Planning Area, including one historic district. Other existing public landholdings include the recently constructed Caltrans administrative and operational facility on Taylor Street. Old San Diego is also the location of a major rail transit station, primarily accommodating light rail service -

2010 Annual Meeting Program

Society for California Archaeology 2010 Annual Meeting March 17-20, 2010 Riverside, California Society for California Archaeology Annual Meeting 2010 1 SOCIETY FOR CALIFORNIA ARCHAEOLOGY TH 44 ANNUAL MEETING, RIVERSIDE MARCH 17–20, 2010 SUMMARY SCHEDULE _______________________________________________________________________________ March 17 – Wednesday AM 10:00 – 5:00 Meeting: SCA Executive Board Meeting; closed (Citrus Heritage) _______________________________________________________________________________ March 17 – Wednesday PM 1:00 – 5:00 Workshop: First Aid for California Artifacts: An Introduction (Arlington) Summary Schedule 1:00 – 5:00 Meeting Registration (West Foyer) ______________________________________________________ March 18 – Thursday AM 7:00 – 12:00 Meeting Registration (West Foyer) 8:00 – 12:00 Bookroom (Ben H. Lewis Hall North) 8:30 – 9:00 Conference Welcome (Ben H. Lewis Hall South) 9:00 – 11:30 Plenary Session: Forging New Frontiers: The Curation Crisis, Stewardship, and Cultural Heritage Management in California Archaeology (Ben H. Lewis Hall South) _______________________________________________________________________________ March 18 – Thursday PM 12:00 – 5:00 Meeting Registration (West Foyer) 12:00 – 5:00 Bookroom (Ben H. Lewis Hall North) 1:00 – 2:30 Symposium 1: Brief Adventures in Alta and Baja California: Two Minutes at a Time (La Sierra) 1:00 – 2:00 Meeting: Riverside County Tribal Representatives; closed (Citrus Heritage) 1:00 – 4:15 Symposium 2: An Inconvenient Ignition: Issues and Implications for Cultural -

Historic Preservation

Old Town, San Diego, Cal. 1885. Courtesy of California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, Ca. 2 HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2.1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 2.2 IDENTIFICATION AND PRESERVATION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES 2.3 EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES AND INCENTIVES HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2 2. Historic Preservation A Prehistoric Cultural Resources Study and a Historic Resources Survey Report were prepared in conjunction GOALS with the Community Plan. The Prehistoric Cultural x Identification and preservation of significant Resources Study for the Old Town Community Plan Update historical resources in Old Town San Diego. describes the pre-history of the Old Town Area; identifies x Identification of educational opportunities and incentives related to historical known significant archaeological resources; provides resources in Old Town. guidance on the identification of possible new significant archaeological resources; and includes recommendations for the treatment of significant archaeological resources. INTRODUCTION The City of San Diego Old Town Community Plan Area The purpose of the City of San Diego General Plan Historic Historic Resources Survey Report: Historic Context & Preservation Element is to preserve, protect, restore and Reconnaissance Survey (Historic Survey Report) provides rehabilitate historical and cultural resources throughout information regarding the significant historical themes the City of San Diego. It is also the intent of the element in the development of Old Town. These documents to improve the quality of the built environment, have been used to inform not only the policies and encourage appreciation for the City’s history and culture, recommendations of the Historic Preservation Element, maintain the character and identity of communities, and but also the land use policies and recommendations contribute to the City’s economic vitality through historic throughout the Community Plan. -

Cultural Resources Inventory Report for the Riverwalk Project, City of San Diego, County of San Diego, California

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY REPORT FOR THE RIVERWALK PROJECT, CITY OF SAN DIEGO, COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Prepared for / Submitted to: Hines 11545 W Bernardo Ct # 204 San Diego, CA 92127 Spindrift Project No. 2017-006 Prepared by Arleen Garcia-Herbst October 2017 8895 Towne Centre Drive #105-248 San Diego, California 92122 Phone: 858-333-7202 Fax: 855-364-3170 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 Section 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Project Location ..................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Project Description ................................................................................................ 1-2 1.3 Regulatory Context Summary ............................................................................... 1-3 1.4 Area of Potential Effects (APE) ............................................................................ 1-4 1.5 Report Organization .............................................................................................. 1-4 Section 2 Setting ............................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Existing Conditions ............................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Regulatory Setting .............................................................................................. -

Identificación E Interpretación De La Herencia Hispana

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Recursos Culturales v REFLEJOS HISPANOS EN EL PAISAJE AMERICANO identificación e interpretación de la herencia hispana ReflejoS hispaNoS eN el Paisaje americaNo ideNtIficacióN e interpretacióN De la heRencia HispaNa Servico de Parques Nacionales Brian D. Joyner 2009 Table of Contents Resumen Ejecutivo ................................................................................... i Agradecimientos .....................................................................................iii Contexto Histórico ...................................................................................1 Territorios españoles en Latinoamérica ......................................................................... 1 “Hispanos” y “latinos”......................................................................................................3 Mexicanos ..........................................................................................................................5 Puertorriqueños ................................................................................................................8 Cubanos ............................................................................................................................10 Dominicanos .....................................................................................................................11 Salvadoreños .................................................................................................................... 12 Colombianos -

Making History by ALLEN HAZARD & ALANA COONS Tuesday, September 6, Was a History-Making Day in the Effort to Reclaim Our Lost Heritage

Summer 2006 Volume 37, Issue 3 SAVING SAN DIEGO’S PAST FOR THE FUTURE LOCAL PARTNERS WITH THE NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION Making History BY ALLEN HAZARD & ALANA COONS Tuesday, September 6, was a history-making day in the effort to reclaim our lost heritage. A coalition of San Diego’s political leaders led by State Senator Christine Kehoe came together in an outstanding show of support and enthusiasm. Present at this historic occasion were Mayor Jerry Sanders; Senator Kehoe; Assembly member Lori Saldaña; City Councilmembers Kevin Faulconer, Donna Frye; Chairperson of the San Diego River Conservancy and City (left to right) SOHO Executive Director Bruce Coons; State Parks Councilmember Toni Atkins; District Director Clarissa District Superintendent Ronie Clark; Senator Christine Kehoe; Falcon represented Senator Denise Moreno-Ducheny; Rob Hutsel, San Diego River Park Foundation; Caltrans District 11 Director Pedro Orso-Delgado; Assembly member Lori Saldaña; Pedro Orso-Delgado, Caltrans District 11 Director; Ronie City Councilmember Donna Frye Clark, State Parks District Superintendent; Gary Gallegos, SANDAG Executive Director; Jeannie Ferrell, Chair of the and phone calling campaign that SOHO members Old Town Community Planning Committee; Fred Grand, bolstered. With Senator Kehoe taking the lead, President of the Old Town Chamber of Commerce; Bruce Assemblywoman Lori Saldaña, and, Councilmember Kevin Coons, SOHO Executive Director; Cindy Stankowski, San Faulconer worked together to coordinate the successful Diego Archaeological Society; Rob Hutsel, San Diego campaign. River Park Foundation; and Eleanor Neely, Chair of the San Diego Presidio Park Council. They all gathered The transfer would add 2.5 acres to the 13-acre Old Town together for a press conference to announce their support San Diego State Historic Park. -

Old Town San Diego State Historic Park, That the Action Really Began to Unfold As South to San Ysidro, California, at the Border of Mexico

CRUISING OUR HISTORIC COASTAL HIGHWAYS • BY MELISSA BRANDZEL Whose Land Is It Anyway? Back in the day—somewhere around twelve o commemorate American thousand to thirteen thousand years ago— Road’s fi ft eenth anniversary this the Kumeyaay made their home here, near year, we’re going all the way back the San Diego River. In 1542, Portuguese to another historical “fi ft een”— explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, working the 1500s, where the history of on behalf of Spain, sailed into San Diego Tthe city we know as San Diego began, in an Bay, befriended the Kumeyaay, had a look area now called Old Town. around, dubbed the place San Miguel, and US HIGHWAY 101 travels from Olympia, Washington, to Stroll through the calm, grassy plaza of took off a few days later. It wasn’t until 1769 Los Angeles via Oregon. Historically the route extended Old Town San Diego State Historic Park, that the action really began to unfold as south to San Ysidro, California, at the border of Mexico. and it might seem as though the place had Father Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà always been this way. In truth, this pocket arrived from Spain to found missions and and a pueblo (town) built by the Spanish of San Diego, known as “the birthplace of presidios here. Th e area was renamed San military. Residents began cultivating gardens California,” wasn’t always so peaceful…or so Diego and became part of New Spain. It was down in Old Town and—perhaps tired of green. A couple hundred years ago, it was a the fi rst European settlement in California. -

Historic Preservation

Old Town, San Diego, Cal. 1885. Courtesy of California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, Ca. 2 HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2.1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 2.2 IDENTIFICATION AND PRESERVATION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES 2.3 EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES AND INCENTIVES HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2 2. Historic Preservation A Prehistoric Cultural Resources Study and a Historic Resources Survey Report were prepared in conjunction GOALS with the Community Plan. The Prehistoric Cultural x Identification and preservation of significant Resources Study for the Old Town Community Plan Update historical resources in Old Town San Diego. describes the pre-history of the Old Town Area; identifies x Identification of educational opportunities and incentives related to historical known significant archaeological resources; provides resources in Old Town. guidance on the identification of possible new significant archaeological resources; and includes recommendations for the treatment of significant archaeological resources. INTRODUCTION The City of San Diego Old Town Community Plan Area The purpose of the City of San Diego General Plan Historic Historic Resources Survey Report: Historic Context & Preservation Element is to preserve, protect, restore and Reconnaissance Survey (Historic Survey Report) provides rehabilitate historical and cultural resources throughout information regarding the significant historical themes the City of San Diego. It is also the intent of the element in the development of Old Town. These documents to improve the quality of the built environment, have been used to inform not only the policies and encourage appreciation for the City’s history and culture, recommendations of the Historic Preservation Element, maintain the character and identity of communities, and but also the land use policies and recommendations contribute to the City’s economic vitality through historic throughout the Community Plan. -

La Casa De Estudillo

THE STORY. twists and surprises. The story of the Casa Thank you for your interest in Old Town de Estudillo is no different and is still being San Diego State Historic Park, part of the LLaa CasaCasa dede La Casa de Estudillo was a social and retold today. California State Parks system. Inquire at the political center of San Diego during California’s Robinson-Rose Visitor Information Center EEstudillo.studillo. Mexican Period, 1821-1846, and into the early or visit our website to fi nd additional ways American Period. Besides serving as the town to experience California’s history. (The Estudillo House.) house of the Estudillos when they were not The Estudillo Museum. on one of their four ranches, the house served as a business offi ce, schoolroom, chapel, 4002 Wallace St. and even as a place of refuge for women and San Diego, CA 92110 children during the American invasion of 1846. 619-220-5422 The Estudillo Family occupied the house for some sixty years. After José Antonio passed www.parks.ca.gov/oldtownsandiego away in 1852, his widow rented rooms to others outside the family, including Benjamin Hayes, a Democratic Party district judge and THE PEPEOPLE.OPLE. historian, and David Hoffman, a surgeon and Democratic Party Assemblyman. José Antonio Estudillo, a The popularity of Helen Hunt Jackson’s wealthy rancher, held many public offi ces book, Ramona, helped launch historic tourism in San Diego. He and other family members and a romanticized perception of San Diego acquired extensive land holdings in the history. Hazel Waterman’s reconstruction county.