Pepys Westminster Walk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 Christopher Thomas Daly College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Daly, Christopher Thomas, "Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625366. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-y42p-8r81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BASILISKS OF THE COMMONWEALTH: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts fcy Christopher T. Daly 1986 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts . s F J i z L s _____________ Author Approved, August 1986 James L. Axtell Dale E. Hoak JamesEL McCord, IjrT DEDICATION To my brother, grandmother, mother and father, with love and respect. iii TABLE OE CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. v ABSTRACT.......................................... vi INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 CHAPTER I. THE PROBLEM OE VAGRANCY AND GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSES TO IT, 1485-1553 7 CHAPTER II. -

Note: Page Numbers in Italic Refer to Figures

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03402-0 — Women of Fortune Linda Levy Peck Index More Information Index Note: Page numbers in italic refer to Figures Abbott, Edward , Frances Bennet , – Abbott, George Grace Bennet , Abbott, Sir Maurice and marriage of daughter Abbott, Robert, scrivener and banker , and marriages of Simon Bennet’s daughters Abbott family , abduction (of heiresses), fear of , Arlington, Isabella, Countess of Abington, Great and Little, Cambridgeshire Arran, Earl of (younger son of Duke of , – Ormond) , foreclosure by Western family , Arthur, Sir Daniel Abington House , Arundel, Alatheia Talbot, Countess of Admiralty Court, and Concord claim – aspirations “Against the Taking Away of Women” and architecture ( statute) George Jocelyn’s , –, Ailesbury, Diana Bruce, Countess of , John Bennet’s , Ailesbury, Robert Bruce, st Earl of , of parish gentry Ailesbury, Thomas Bruce, nd Earl of Astell, Mary and Frances, Countess of Salisbury , , Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, Barnes’strial , at on Grace Bennet , , Albemarle, nd Duke of Bacon, Francis Alfreton, Derbyshire , , Bagott, Sir Walter, Bt Andrewes, Lancelot, Bishop Bahia de Todos os Santos, Brazil Andrewes, Thomas, merchant Baines, Dr. Thomas Andrewes, Thomas, page Baker, Fr. Anglo-Dutch War (–) , Bancroft, John, Archbishop of Canterbury Anne, Queen , Bank of England Appleby School shares in apprenticeship banking Bennets in Mercers’ Company early forms Charles Gresley private , gentlemen apprentices –, , – see also moneylending -

Student Days at the Inns of Court

STUDENT DAYS AT THE INNS OF COURT.* Fortescue tells us that when King John fixed the Court of Common Pleas at Westminster, the professors of the municipal law who heretofore had been scattered about the kingdom formed themselves into an aggregate body "wholly addicted to the study of the law." This body, having been excluded from Oxford and Cambridge where the civil and canon laws alone were taught, found it necessary to establish a university of its own. This it did by purchasing at various times certain houses between the City of Westminster, where the King's courts were held, and the City of London, where they could obtain their provisions. The nearest of these institutions to the City of London was the Temple. Passing through Ludgate, one came to the bridge over the Fleet Brook and continued down Fleet Street a short distance to Temple Bar where were the Middle, Inner and Outer Temples. The grounds of the Temples reached to the bank of the Thames and the barges of royalty were not infrequently seen drawn up to the landing, when kings and queens would honor the Inns with their presence at some of the elaborate revels. For at Westminster was also the Royal Palace and the Abbey, and the Thames was an easy highway from the market houses and busi- ness offices of London to the royal city of Westminster. Passage on land was a far different matter and at first only the clergy dared risk living beyond the gates, and then only in strongly-walled dwellings. St. -

Careers at the Chancery Bar

Careers at the Chancery Bar With the right qualifications, where you come from doesn’t matter, where you’re going does. “if you are looking for a career which combines intellectual firepower, communication skills and the ability to provide practical solutions to legal problems, then your natural home is the Chancery Bar” 2 Chancery Bar Association Chancery Bar Association 1 Welcome to the Chancery Bar Do you enjoy unravelling the knottiest of legal problems? Would you relish the prospect of your appearances in court helping to develop cutting-edge areas of law? How does advising major commercial concerns to put together a complex transaction appeal? Would you like to assist organisations to achieve their commercial goals, and support and guide individuals at times of great personal stress? If your answer to any of these questions is “Yes”, then the Chancery Bar may be the career for you. Barristers who specialise in the areas of property, business and finance law most closely associated with the Chancery Division of the High Court are called “Chancery barristers” and, collectively, the “Chancery Bar”. Of the 15,000 barristers practising in England and Wales, about 1,200 specialise in Chancery work. Most are based in London but there are other important regional centres, such as Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Leeds and Manchester. In recent years the nature of Chancery work has changed dramatically. It still includes the important work traditionally undertaken in the Chancery Division, but the expansion and development of commercial activity, together with the increasingly complex matters that arise out of that activity, have widened its scope significantly. -

Chapter 3: History and Land Use of City Hall Park

Chapter 3: History and Land Use of City Hall Park A. Background History Alyssa Loorya Introduction This section is edited from the forthcoming doctoral dissertation from Loorya on City Hall Park. Loorya’s work references several graduate student projects associated with the overall City Hall Park project, most notably the Master’s theses of Mark Cline Lucey (included as the next section) and Julie Anidjar Pai as well as reports by Elizabeth M. Martin, Diane George, Kirsten (Davis) Smyth, and Jennifer Borishansky. These reports are presented in Chapter 6. This section outlines the history of the City Hall Park area. To provide for proper context, a general history of the development of the lower Manhattan area is presented first to provide a more complete picture of overall project area. City Hall Park is a relatively small triangular parcel of land (8.8 acres) within New York City’s Manhattan Island. It is bounded to the north by Chambers Street, to the east by Park Row, to the west by Broadway. It began as a cow pasture and today houses the seat of government for the nation’s largest city. The general history of City Hall Park is fairly well documented though only in a single comprehensive source.1 The changing uses of City Hall Park from the beginning of the colonial periodFig. 3-1: of theCity midHall nineteenthPark Location century reflect 1 The Master’s Thesis City Hall Park: An Historical Analysis by Mark Cline Lucey, 2003, (below) chronicles the physical development of City Hall Park from the Dutch Colonial period to the mid-nineteenth century. -

The Significance of Anya Seton's Historical Fiction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Breaking the cycle of silence : the significance of Anya Seton's historical fiction. Lindsey Marie Okoroafo (Jesnek) University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Gender Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Language and Literacy Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public History Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Secondary Education Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Okoroafo (Jesnek), Lindsey Marie, "Breaking the cycle of silence : the significance of Anya Seton's historical fiction." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2676. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2676 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional -

Year 7 History Project

Year 7 History Project Middle Ages - Power and Protest Session 1: King Edward I • In the following slides you will find information relating to: • Edward and parliament • Edward and Wales • Edward and the War of Independence Edward I • Edward facts • Edward was born in 1239 • In 1264 Edward was held prisoner when English barons rebelled against his father Henry III. • In 1271 Edward joined a Christian Crusade to try and free Jerusalem from Muslim control • Edward took the throne in 1272. • Edward fought a long campaign to conquer Wales • Edward built lots of castles in Wales such as Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech castles • Edward had two nicknames - 'Longshanks' because he was so tall and the 'Hammer of the Scots' for obvious reasons • Edward’s war with Scotland eventually brought about his death when he died from sickness in 1307 when marching towards the Scottish Border. Llywelyn Ap Gruffudd • In 1275 Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales refused to pay homage (respect) to King Edward I of England as he believed himself ruler of Wales after fighting his own uncles for the right. • This sparked a war that would result in the end of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the last) who was killed fighting the English in 1282 after several years of on off warfare. • Edward I destroyed the armies of Llywelyn when they revolted against England trying to take complete control of Wales. • As a result Llywelyn is known as the last native ruler of Wales. • After his death Edward I took his head from his body and placed it on a spike in London to deter future revolts. -

Legal Profession in the Middle Ages Roscoe Pound

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 19 | Issue 3 Article 2 3-1-1944 Legal Profession in the Middle Ages Roscoe Pound Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Roscoe Pound, Legal Profession in the Middle Ages, 19 Notre Dame L. Rev. 229 (1944). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol19/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Copyright in the Pound lectures is reserved by Dean Emeritus Roscoe Pound, Harvard Law School, Harvard University." II THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN THE MIDDLE AGES 1 PROCTORS AND ADVOCATES IN THE CIVIL AND THE CANON LAW W E have seen that in Roman law the three functions of V agency or representation in litigation, advocacy, and advice -the functions of procurator or attorney, advocate, and jurisconsult-had become differentiated and had each attained a high degree of development. Also we have seen how by the time of Justinian the jurisconsult had become a law teacher, so that for the future, in continental Europe, the advocate's function and the jurisconsult's function of advis- ing were merged and the term jurisconsult was applied only to teachers and writers. Germanic law brought back into western Europe the ideas of primitive law as to representation in litigation. Parties were required to appear in person and conduct their cases in person except in case of dependents. -

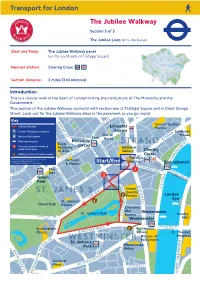

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

{BREWERS} ACC/2305 Page 1 Reference Description Dates BARCLAY P

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 COURAGE BARCLAY AND SIMONDS LIMITED {BREWERS} ACC/2305 Reference Description Dates BARCLAY PERKINS AND COMPANY LIMITED: CORPORATE Minutes and related papers ACC/2305/01/0001/001 'Partners record book' minutes of partners' Jul 1877 - Jan decisions 1897 ACC/2305/01/0001/002 Note of continued credit agreements with Mar 1878 Apr Messrs. Tyrer and Son, Liverpool 1879 Enclosed in ACC/2305/01/001/1 ACC/2305/01/0002 Board and general meeting minute book Jun 1895 - Oct Indexed 1898 Former Reference: 'No.1' ACC/2305/01/0003 Board and general meeting minute book Oct 1898 - Dec Indexed 1900 Former Reference: 'No.2' ACC/2305/01/0004 Board and general meeting minute book Jan 1901 - Indexed Nov 1902 Former Reference: 'No.3' ACC/2305/01/0005 Board and general meeting minute book Nov 1902 - Indexed Aug 1904 Former Reference: 'No.4' ACC/2305/01/0006 Board and general meeting minute book Sep 1904 - Indexed May 1906 Former Reference: 'No.5' ACC/2305/01/0007 Board and general meeting minute book Jun 1906 - Indexed Nov 1907 Former Reference: 'No.6' ACC/2305/01/0008 Board and general meeting minute book Nov 1907 - Indexed Jun 1909 Former Reference: 'No.7' ACC/2305/01/0009/001 Board and general meeting minute book Jun 1909 - Feb Indexed 1911 Former Reference: 'No.8' ACC/2305/01/0009/002 Note of appointments of director etc. Mar 1910 Enclosed in ACC/2305/01/009/1 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 COURAGE BARCLAY AND SIMONDS LIMITED {BREWERS} ACC/2305 Reference Description Dates ACC/2305/01/0010 Board, committee and general -

Directory of Clubs – Season 2017-2018

DIRECTORY OF CLUBS – SEASON 2017-2018 Parent County Football Associations are shown in italics as follows: - Kent FA – KFA • London FA – LFA • Surrey FA – SCFA • Amateur FA - AFA AEI SPORTS FC KFA (2013) Division Three Central & East Secretary: Peter Stanton, 51 Bryant Road, Strood, Kent ME2 3EP Tel: (H) 01634 318569 (M) 07834 980113 - email: [email protected] Ground: Wested Meadow Ground, Eynsford Road, Crockenhill, Kent BR8 8EJ - Tel: 01322 666067 Colours: Black & White Striped Shirts, Black Shorts, Black Socks Alternative: Blue Shirts, Blue Shorts, Blue Socks Fixture Secretary: As Secretary Emergency Contact: Michael Betts, 11 Wheatcroft Grove, Rainham, Kent ME8 9JF Tel: (M) 07850 473451 - email: [email protected] Chairman: As Secretary AFC ASHFORD ATHLETIC KFA (2013) Division Three Central & East Secretary: Jackie Lawrence, 31 St. Martins Road, Deal, Kent CT14 9NX Tel: (M) 07842 746686 - email: [email protected] Ground: Homelands Stadium, Ashford Road, Kingsnorth, Ashford, Kent TN26 1NJ - Tel: 01233 611838 Colours: Red Shirts, Black Shorts, Black Socks Alternative: Royal Blue Shirts, Royal Blue Shorts, White Socks Fixture Secretary: As Secretary Emergency Contact: Stuart Kingsnorth - Tel (M) 07850 865805 (B) 07725 002681 – email: [email protected] Chairman: As Emergency Contact AFC BEXLEY KFA (2008) Division Three West Secretary: Mark Clark, 18 Woodside Road, Bexleyheath, Kent DA7 6JZ Tel: (H) 01322 409979 (M) 07900 804155 - email: [email protected] Ground: Bakers Fields, Perry Street, Crayford, Kent DA1