081 Chatham Petrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Hearings Panel

UNDER THE Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 (the Act) IN THE MATTER OF A Decision-making Committee appointed to consider a marine consent application by Chatham Rock Phosphate Limited to undertake mining of phosphorite nodules on the Chatham Rise STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF GRAEME ANDREW SYDNEY TAYLOR FOR THE CROWN 12 September 2014 CROWN LAW TE TARI TURE O TE KARAUNA PO Box 2858 WELLINGTON 6140 Tel: 04 472 1719 Fax: 04 473 3482 Counsel acting: Jeremy Prebble Email: [email protected] Telephone: 04 494 5545 Eleanor Jamieson Email: [email protected] Telephone: 04 496 1915 CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 Qualifications and experience 5 Code of Conduct 5 Material considered 6 SCOPE OF EVIDENCE 7 THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CHATHAM RISE FOR 7 SEABIRDS Importance of the Chatham Rise to the critically 11 endangered Chatham Island taiko Importance of the Chatham Rise to the endangered 14 Chatham petrel THE POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF THIS APPLICATION 16 ON VARIOUS SEABIRDS Operational light attraction 16 Other possible effects of the mining operations 18 including ecosystem changes and oil spills CONDITIONS 20 REFERENCES 24 APPENDIX 1: Seabird species of the Chatham Rise 26 DOCDM-1462846 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. The Chatham Rise is the most productive ocean region in the New Zealand EEZ, due to the mixing of two major ocean current systems (the sub-tropical convergence). These productive waters provide one of the five key ocean habitats for seabirds in New Zealand. A definitive list of seabird species using this region is not available due to a lack of systematic seabird surveys. -

(Pterodroma Axillaris) and Broad-Billed Prions (Pachyptila Vittata): Investigating Techniques to Reduce the Effects of Burrow Competition

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Differences in burrow site preferences between Chatham petrels (Pterodroma axillaris) and broad-billed prions (Pachyptila vittata): investigating techniques to reduce the effects of burrow competition. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Animal Ecology at Lincoln University by w. 1. Sullivan Lincoln University 2000 Frontispiece Figure 1. Chatham petrel (Pterodroma axil/oris) Figure 2. Broad-billed prion (Pachyptila vittata) Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of M. Sc. Differences in burrow site preferences between Chatham petrels (Pterodroma axillaris) and broad-billed prions (Pachyptila vittata): investigating techniques to reduce the effects of burrow competition. by W. J. Sullivan The Chatham petrel (Pterodroma axillaris Salvin) is an endangered species endemic to the Chatham Islands .. It is currently restricted to a population of less than 1000 individuals on South East Island. The key threat to breeding success is interference to chicks by broad- billed prions (Pachyptila vittata Forster), when they prospect for burrows for their oncoming breeding season. -

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, and CONSERVATION of the SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides Georgicus) in NEW ZEALAND

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, AND CONSERVATION OF THE SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides georgicus) IN NEW ZEALAND BY JOHANNES HARTMUT FISCHER A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology School of Biological Sciences Faculty of Sciences Victoria University of Wellington September 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Heiko U. Wittmer, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington. © Johannes Hartmut Fischer. September 2016. Ecology, Taxonomic Status and Conservation of the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus) in New Zealand. ABSTRACT ROCELLARIFORMES IS A diverse order of seabirds under considerable pressure P from onshore and offshore threats. New Zealand hosts a large and diverse community of Procellariiformes, but many species are at risk of extinction. In this thesis, I aim to provide an overview of threats and conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes in general, and an assessment of the remaining terrestrial threats to the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus; SGDP), a Nationally Critical Procellariiform species restricted to Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), post invasive species eradication efforts in particular. I reviewed 145 references and assessed 14 current threats and 13 conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes (n = 48) in a meta-analysis. I then assessed the terrestrial threats to the SGDP by analysing the influence of five physical, three competition, and three plant variables on nest-site selection using an information theoretic approach. Furthermore, I assessed the impacts of interspecific interactions at 20 SGDP burrows using remote cameras. Finally, to address species limits within the SGDP complex, I measured phenotypic differences (10 biometric and eight plumage characters) in 80 live birds and 53 study skins, as conservation prioritisation relies on accurate taxonomic classification. -

Threats to Seabirds: a Global Assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P

1 Threats to seabirds: a global assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P. Dias1*, Rob Martin1, Elizabeth J. Pearmain1, Ian J. Burfield1, Cleo Small2, Richard A. 5 Phillips3, Oliver Yates4, Ben Lascelles1, Pablo Garcia Borboroglu5, John P. Croxall1 6 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1 - BirdLife International. The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK 10 2 - BirdLife International Marine Programme, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, SG19 2DL 11 3 – British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 12 Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 13 4 – Centre for the Environment, Fishery and Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, NR33, UK 14 5 - Global Penguin Society, University of Washington and CONICET Argentina. Puerto Madryn U9120, 15 Chubut, Argentina 16 * Corresponding author: Maria Dias, [email protected]. BirdLife International. The David 17 Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK. Phone: +44 (0)1223 747540 18 19 20 Acknowledgements 21 We are very grateful to Bartek Arendarczyk, Sophie Bennett, Ricky Hibble, Eleanor Miller and Amy 22 Palmer-Newton for assisting with the bibliographic review. We thank Rachael Alderman, Pep Arcos, 23 Jonathon Barrington, Igor Debski, Peter Hodum, Gustavo Jimenez, Jeff Mangel, Ken Morgan, Paul Sagar, 24 Peter Ryan, and other members of the ACAP PaCSWG, and the members of IUCN SSC Penguin Specialist 25 Group (Alejandro Simeone, Andre Chiaradia, Barbara Wienecke, Charles-André Bost, Lauren Waller, Phil 26 Trathan, Philip Seddon, Susie Ellis, Tom Schneider and Dee Boersma) for reviewing threats to selected 27 species. We thank also Andy Symes, Rocio Moreno, Stuart Butchart, Paul Donald, Rory Crawford, 28 Tammy Davies, Ana Carneiro and Tris Allinson for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on earlier 29 versions of the manuscript. -

Burrow Competition Between Broad-Billed Prions (Pachyptila Vittata) and the Endangered Chatham Petrel (Pterodroma Axillaris)

Burrow competition between broad-billed prions (Pachyptila vittata) and the endangered Chatham petrel (Pterodroma axillaris) SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 167 NW Was, WJ Sullivan and K-J Wilson Published by Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Science for Conservation presents the results of investigations by DOC staff, and by contracted science providers outside the Department of Conservation Publications in this series are internally and externally peer reviewed Publication was approved by the Manager, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington © December 2000, Department of Conservation ISSN 11732946 ISBN 0478220146 Cataloguing-in-Publication data Was, Nicolette Winneke Burrow competition between broad-billed prions (Pachyptila vittata) and the endangered Chatham petrel (Pterodroma axillaris) / NW Was, WJ Sullivan and K-J Wilson Wellington, NZ : Dept of Conservation, 2000 1 v ; 30 cm (Science for conservation, 1173-2946 ; 167) Cataloguing-in-Publication data - Includes bibliographical references ISBN 0478220146 1 Pterodroma axillaris 2 Pachyptila vittata 3 Rare birds--New Zealand--Chatham Islands I Sullivan, W J II Wilson, Kerry-Jayne III Title Series: Science for conservation (Wellington, NZ) ; 167 CONTENTS Abstract 5 1 Introduction 6 11 Aims 6 12 Study objectives 7 13 Study site 7 PART 1 BURROW OCCUPANCY AND PROSPECTING BEHAVIOURS OF BROAD-BILLED PRIONS 9 2 Burrow occupancy 9 21 Introduction 9 22 Methods 9 221 Burrow occupancy 9 222 Blockading -

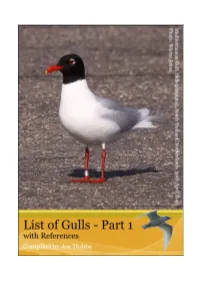

List of Gulls Part 1 with References

Introduction This is the final version of the Gulls (Part 1) list, no further updates will be made. It includes all those species of Gull that are not included in the genus Larus. Grateful thanks to Wietze Janse and Dick Coombes for the cover images and all those who responded with constructive feedback. All images © the photographers. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2019. IOC World Bird List. Available from: https://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 9.1 accessed January 2019]). Final Version Version 1.4 (January 2019). Cover Main image: Mediterranean Gull. Hellegatsplaten, South Holland, Netherlands. 30th April 2010. Picture by Wietze Janse. Vignette: Ivory Gull. Baltimore Harbour, Co. Cork, Ireland. 4th March 2009. Picture by Richard H. Coombes. Species Page No. Andean Gull [Chroicocephalus serranus] 20 Audouin's Gull [Ichthyaetus audouinii] 38 Black-billed Gull [Chroicocephalus bulleri] 19 Black-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus ridibundus] 21 Black-legged Kittiwake [Rissa tridactyla] 6 Bonaparte's Gull [Chroicocephalus philadelphia] 16 Brown-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus] 20 Brown-hooded Gull [Chroicocephalus maculipennis] 20 Dolphin Gull [Leucophaeus scoresbii] 32 Franklin's Gull [Leucophaeus pipixcan] 35 Great Black-headed Gull [Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus] 43 Grey Gull [Leucophaeus -

Philopatry and Population Genetics Across Seabird Taxa

PHILOPATRY AND POPULATION GENETICS ACROSS SEABIRD TAXA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT (ECOLOGY, EVOLUTION, AND CONSERVATION BIOLOGY) MAY 2018 By Carmen C. Antaky Thesis Committee: Melissa Price, Chairperson Tomoaki Miura Robert Toonen Lindsay Young Keywords: seabirds, dispersal, philopatry, endangered species, population genetics Copyright 2018 Carmen C. Antaky All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis, my Master’s work, would not have been possible without the help and valuable assistance of many others. Firstly, thank you to my advisor Melissa Price for guiding me through my Master’s degree. Her support has made me a better researcher, scientific writer, and conservationist. I would like to thank my committee members Rob Toonen, Lindsay Young, and Tomoaki Miura for their feedback, support, and encouragement. Thank you Lindsay for your expert advice on all things seabirds and being an incredible role model. Thank you Rob for welcoming me into your lab and special thanks to Ingrid Knapp for guidance throughout my lab work. I would like to thank Tobo lab members Emily Conklin, Derek Kraft, Evan Barba, and Zac Forsman for support with genetic data analysis. I would also like to thank all the members of the Hawaiʻi Wildlife Ecology Lab, especially to Jeremy Ringma and Kristen Harmon for their support and friendship. I would like to thank my major collaborators on my project who supplied samples, a wealth of information, and for helping me in the field, especially Andre Raine of the Kauaʻi Endangered Seabird Recovery Project, Nicole Galase at Pōhakuloa Training Area, and Tracy Anderson at Save Our Shearwaters. -

Spatial Ecology, Phenological Variability and Moulting Patterns of the Endangered Atlantic Petrel Pterodroma Incerta

Vol. 40: 189–206, 2019 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published November 14 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00991 Endang Species Res Contribution to the Special ‘Biologging in conservation’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Spatial ecology, phenological variability and moulting patterns of the Endangered Atlantic petrel Pterodroma incerta Marina Pastor-Prieto1,*, Raül Ramos1, Zuzana Zajková1,2, José Manuel Reyes-González1, Manuel L. Rivas1, Peter G. Ryan3, Jacob González-Solís1 1Institut de Recerca de la Biodiversitat (IRBio) and Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals (BEECA), Universitat de Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 2Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes (CEAB-CSIC), 17300 Girona, Spain 3FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST-NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa ABSTRACT: Insights into the year-round movements and behaviour of seabirds are essential to better understand their ecology and to evaluate possible threats at sea. The Atlantic petrel Ptero- droma incerta is an Endangered gadfly petrel endemic to the South Atlantic Ocean, with virtually the entire population breeding on Gough Island (Tristan da Cunha archipelago). We describe adult phenology, habitat preferences and at-sea activity patterns for each phenological phase of the annual cycle and refine current knowledge about its distribution, by using light-level geoloca- tors on 13 adults over 1−3 consecutive years. We also ascertained moulting pattern through stable isotope analysis (SIA) of nitrogen and carbon in feathers from 8 carcasses. On average, adults started their post-breeding migration on 25 December, taking 10 d to reach their non-breeding areas on the South American shelf slope. The pre-breeding migration started around 11 April and took 5 d. -

Cookilaria Petrels in the Eastern Pacific Ocean: Identification and Distribution

SCIENCE msspecimens. We scoredcharacters includingmantle color, tail pattern, andhead pattern; sketched head and rectrixpatterns; and took measure- COOKILARIAPETRELS mentsofculmen length, bill depth, andtail length,and measured indi- vidual rectrices to determine tail shape.Wing lengthswere obtained INTHE EASTERN fromthe literature and from speci- mentags, although it islikely these werenot all taken by the same meth- PACIFICOCEAN' ods. Biometrics from this review will appearin PartII of thispaper. Both authors have studied Cook's Petrels IDENTIFICATIOANDoff California, and Bailey participat- ed in an April 1989 cruisethat recorded113 Cook's Petrels (Bailey et DISTRIBUTION al. 1989). Roberson observed seabirds in the eastern Pacific, August-December1989, on a NOAA- PartI ofa Two-PartSeries sponsoredsurvey. He obtainedexpe- rience with hundreds of Cook's, White-winged,and Black-winged petrels,and a few Stejneger'sand byDon Roberson and "Collared"petrels. Illustrator Keith StephenE Bailey Hansen, whose color plate will appearin PartII, alsohas experience THE SMALL PTERODROMA PETRELS and known distribution of all small withmost of thesespecies in theeast- of the subgenusCookilaria are Pterodroma in the eastern Pacific. We ern Pacific. amongthe least understood seabirds review six species:Cook's Petrel, Neither authorhas field experi- In the world. Two species,Cook's Defilippe'sPetrel, Pycroft's Petrel, encewith Defilippe'sor Pycroft's Petrel (P. cookii)and Stejneger's Stejneger'sPetrel, White-winged petrels.We discussedthese species Petrel(P. longirostris),have been Petrel(P. leucoptera, including "Col- withobservers who had field experi- recorded off the west coast of North laredPetrel" [P. (l.) brevipes]),and ence(e.g., J. A. Barde,C. Corben,B. America;others have been tentative- Black-wingedPetrel (P. -

A Hybrid Gadfly Petrel Suggests That Soft-Plumaged Petrels (Pterodroma Mollis) Had Colonised the Antipodes Islands by the 1920S

290 Notornis, 2013, Vol. 60: 290-295 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. A hybrid gadfly petrel suggests that soft-plumaged petrels (Pterodroma mollis) had colonised the Antipodes Islands by the 1920s ALAN J.D. TENNYSON* Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand HAYLEY A. LAWRENCE Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution, Institute of Molecular BioSciences, Massey University, Private Bag 102904, NSMC, Auckland, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington, New Zealand MICHAEL J. IMBER** 6 Hillcrest Lane, Levin 5500, New Zealand Abstract A unique Pterodroma petrel shot at sea near the Antipodes Islands in 1926 has features intermediate between white-headed petrel (Pterodroma lessonii) and soft-plumaged petrel (Pt. mollis). Its mitochondrial DNA indicates that its mother was a Pt. mollis and we conclude that it is a hybrid. We theorise that Pt. mollis had begun colonising Antipodes Island by the 1920s and some pairing with the locally abundant congeneric Pt. lessonii occurred. Hybridisation in Procellariiformes is rare worldwide but several cases have now been reported from the New Zealand region. Tennyson, A.J.D.; Lawrence, H.A.; Taylor, G.A.; Imber, M.J. 2013. A hybrid gadfly petrel suggests that soft-plumaged petrels (Pterodroma mollis) had colonised the Antipodes Islands by the 1920s. Notornis 60 (4): 290-295. Keywords soft-plumaged petrel; Pterodroma mollis; mitochondrial DNA; hybrid; Antipodes Islands INTRODUCTION Expedition, used in Murphy & Pennoyer’s (1952) On 17 Feb 1926 an unusual male gadfly petrel review paper on the larger gadfly petrels, because (Pterodroma sp.) (American Museum of Natural its small dimensions (Table 1) are not included in History AMNH 211660) was collected at sea by the Murphy & Pennoyer’s Table 2 data for Pt. -

Pterodromarefs V1.15.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2017 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Michael O’Keeffe and Kieran Fahy for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds). 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.1 accessed January 2017]). Version Version 1.15 (March 2017). Cover Main image: Soft-plumaged Petrel. At sea, north of the Falkland Islands. 11th February 2009. Picture by Michael O’Keeffe. Vignette: Soft-plumaged Petrel. At sea, north of the Falkland Islands. 11th February 2009. Picture by Kieran Fahy. Species Page No. Atlantic Petrel [Pterodroma incerta] 10 Barau's Petrel [Pterodroma baraui] 27 Bermuda Petrel [Pterodroma cahow] 19 Black-capped Petrel [Pterodroma hasitata] 20 Black-winged Petrel [Pterodroma nigripennis] 31 Bonin Petrel [Pterodroma hypoleuca] 32 Chatham Islands Petrel [Pterodroma axillaris] 32 Collared Petrel [Pterodroma brevipes] 34 Cook's Petrel [Pterodroma cookii] 34 De Filippi's Petrel [Pterodroma defilippiana] 35 Desertas Petrel [Pterodroma deserta] 18 Fea's Petrel [Pterodroma feae] 16 Galapágos Petrel [Pterodroma phaeopygia] 29 Gould's Petrel -

Future Directions in Conservation Research on Petrels and Shearwaters

fmars-06-00094 March 15, 2019 Time: 16:47 # 1 REVIEW published: 18 March 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00094 Future Directions in Conservation Research on Petrels and Shearwaters Edited by: Airam Rodríguez1*, José M. Arcos2, Vincent Bretagnolle3, Maria P. Dias4,5, Mark Meekan, Nick D. Holmes6, Maite Louzao7, Jennifer Provencher8, André F. Raine9, Australian Institute of Marine Science Francisco Ramírez10, Beneharo Rodríguez11, Robert A. Ronconi12, Rebecca S. Taylor13,14, (AIMS), Australia Elsa Bonnaud15, Stephanie B. Borrelle16, Verónica Cortés2, Sébastien Descamps17, Reviewed by: Vicki L. Friesen13, Meritxell Genovart18, April Hedd19, Peter Hodum20, Luke Einoder, Grant R. W. Humphries21, Matthieu Le Corre22, Camille Lebarbenchon23, Rob Martin4, Northern Territory Government, Edward F. Melvin24, William A. Montevecchi25, Patrick Pinet26, Ingrid L. Pollet8, Australia Raül Ramos10, James C. Russell27, Peter G. Ryan28, Ana Sanz-Aguilar29, Dena R. Spatz6, Scott A. Shaffer, 9 30 28,31 32 San Jose State University, Marc Travers , Stephen C. Votier , Ross M. Wanless , Eric Woehler and 33,34 United States André Chiaradia * *Correspondence: 1 Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Estación Biológica de Doñana, CSIC, Seville, Spain, 2 Marine Programme, Airam Rodríguez SEO/BirdLife, Barcelona, Spain, 3 Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, CNRS and Université de La Rochelle, Chizé, [email protected] France, 4 BirdLife International, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 5 Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre (MARE), ISPA – André Chiaradia Instituto Universitário,