Oregon's 10 Most Endangered Places 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost in Coos

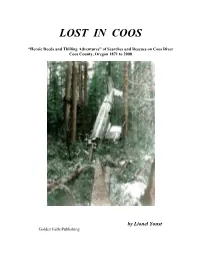

LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Golden Falls Publishing LOST IN COOS Other books by Lionel Youst Above the Falls, 1992 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, 1997 with William R. Seaburg, Coquelle Thompson, Athabaskan Witness, 2002 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, (paper) 2002 Above the Falls, revised second edition, 2003 Sawdust in the Western Woods, 2009 Cover photo, Army C-46D aircraft crashed near Pheasant Creek, Douglas County – above the Golden and Silver Falls, Coos County, November 26, 1945. Photo furnished by Alice Allen. Colorized at South Coast Printing, Coos Bay. Full story in Chapter 4, pp 35-57. Quoted phrase in the subtitle is from the subtitle of Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, by Orville Dodge (Salem, OR: Capital Printing Co., 1898). LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River, Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Including material by Ondine Eaton, Sharren Dalke, and Simon Bolivar Cathcart Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2011 by Lionel Youst 2nd impression Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-3-2 (pbk) Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County – Douglas County Wilderness Survival, case studies Library of Congress cataloging data HV6762 Dewey Decimal cataloging data 363 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Lost in Coos Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs To contact the publisher Printed at Portland State Bookstore’s Lionel Youst Odin Ink 12445 Hwy 241 1715 SW 5th Ave Coos Bay, OR 97420 Portland, OR 97201 www.youst.com for copies: [email protected] (503) 226-2631 ext 230 To Desmond and Everett How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. -

Bıoenu V( Land Management in U›E5v›I

'Me Wíldemefif Eevíew P›v5›Aın v( tfie Bıoenu v( Land Management in U›e5v›ı _ " ;.` › › __. V L i_ „_ 4 ;' ~ gp ""! ¬~ «nvıvq f 1 -4-" _ ._ , 4_&,;¬__§?~~..„ V ıdı; "^. \-*_ ~¬¬ Q 1.z,“-_ ,._§,.';;.è,;;¶±„»_§ ' 1 4. _ _ı-?L_V wı -_ _` ' “T `;",~=:.f~ "_ ';1f“-=".f=«'í~.'›._ 2* T e \ ' "§11 ` `~. xx« (Part Une) Array Kerr ~OSPlR(5 lrwfr March 19/8 THE WILDERNESS REVIEW PROGRAM OF THE BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT IN OREGON PART I Andy Kerr OSPIRG Intern March, 1978 This study is dedicated to those Bureau of Land Management personnel who know what is right for the land and are doing their best to see that it is done by the Bureau. They work under difficult circurs'ances. But with them on the inside and us on the outside, changes are being made, Someday they may all come out of the rloset victorious. Copyright l978 by Oregon Student Public Interest Research Group. Individuals may reproduce or quote portions of this handbook For academic or cítizen action uses, but reproduction for commercial purposes is stríctly prohihíted. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must thank several persons who knowingly, and unknowingly, aided in this study. l'm sure that l'm forgetting some. First the BLM agency people: Ken white and Don Geary (Oregon State Office); Warren Edinger, Ron Rothschadl, and Bob Carothers (Medford District); and Dale Skeesick, Bill Power, Larry Scofield, Jerry Mclntire, Warren Tausch, John Rodosta, Scott Abdon. Jenna Gaston, Karl Bambe, and Paul Kuhns (Salem District). Bob Burkholder (U_S, Fish and Wildlife Service) was most helpful with the Oregon Islands Study. -

A Bill to Designate Certain National Forest System Lands in the State of Oregon for Inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for Other Purposes

97 H.R.7340 Title: A bill to designate certain National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for other purposes. Sponsor: Rep Weaver, James H. [OR-4] (introduced 12/1/1982) Cosponsors (2) Latest Major Action: 12/15/1982 Failed of passage/not agreed to in House. Status: Failed to Receive 2/3's Vote to Suspend and Pass by Yea-Nay Vote: 247 - 141 (Record Vote No: 454). SUMMARY AS OF: 12/9/1982--Reported to House amended, Part I. (There is 1 other summary) (Reported to House from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs with amendment, H.Rept. 97-951 (Part I)) Oregon Wilderness Act of 1982 - Designates as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System the following lands in the State of Oregon: (1) the Columbia Gorge Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (2) the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (3) the Badger Creek Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (4) the Hidden Wilderness in the Mount Hood and Willamette National Forests; (5) the Middle Santiam Wilderness in the Willamette National Forest; (6) the Rock Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (7) the Cummins Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (8) the Boulder Creek Wilderness in the Umpqua National Forest; (9) the Rogue-Umpqua Divide Wilderness in the Umpqua and Rogue River National Forests; (10) the Grassy Knob Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou National Forest; (11) the Red Buttes Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou -

OR Wild -Backmatter V2

208 OREGON WILD Afterword JIM CALLAHAN One final paragraph of advice: do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am — a reluctant enthusiast.... a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of your- selves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it is still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for awhile and contemplate the precious still- ness, the lovely mysterious and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive and I promise you this much: I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men with their hearts in a safe-deposit box and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this: you will outlive the bastards. —Edward Abbey1 Edward Abbey. Ed, take it from another Ed, not only can wilderness lovers outlive wilderness opponents, we can also defeat them. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men (sic) UNIVERSITY, SHREVEPORT UNIVERSITY, to do nothing. MES SMITH NOEL COLLECTION, NOEL SMITH MES NOEL COLLECTION, MEMORIAL LIBRARY, LOUISIANA STATE LOUISIANA LIBRARY, MEMORIAL —Edmund Burke2 JA Edmund Burke. 1 Van matre, Steve and Bill Weiler. -

Public Law 98-328-June 26, 1984

98 STAT. 272 PUBLIC LAW 98-328-JUNE 26, 1984 Public Law 98-328 98th Congress An Act June 26, 1984 To designate certain national forest system and other lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System, and for other purposes. [H.R. 1149] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Oregon United States ofAmerica in Congress assembled, That this Act may Wilderness Act be referred to as the "Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984". of 1984. National SEc. 2. (a) The Congress finds that- Wilderness (1) many areas of undeveloped National Forest System land in Preservation the State of Oregon possess outstanding natural characteristics System. which give them high value as wilderness and will, if properly National Forest preserved, contribute as an enduring resource of wilderness for System. the ben~fit of the American people; (2) the Department of Agriculture's second roadless area review and evaluation (RARE II) of National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon and the related congressional review of such lands have identified areas which, on the basis of their landform, ecosystem, associated wildlife, and location, will help to fulfill the National Forest System's share of a quality National Wilderness Preservation System; and (3) the Department of Agriculture's second roadless area review and evaluation of National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon and the related congressional review of such lands have also identified areas which do not possess outstand ing wilderness attributes or which possess outstanding energy, mineral, timber, grazing, dispersed recreation and other values and which should not now be designated as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System but should be avail able for nonwilderness multiple uses under the land manage ment planning process and other applicable laws. -

Umpqua National Forest

Travel Management Plan ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Umpqua National Forest Pacific March 2010 Northwest Region The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. TRAVEL MANAGEMENT PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT LEAD AGENCY USDA Forest Service, Umpqua National Forest COOPERATING AGENCY Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife RESPONSIBLE OFFICIAL Clifford J. Dils, Forest Supervisor Umpqua National Forest 2900 NW Stewart Parkway Roseburg, OR 97471 Phone: 541-957-3200 FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT Scott Elefritz, Natural Resource Specialist Umpqua National Forest 2900 NW Stewart Parkway Roseburg, OR 97471 Phone: 541-957-3437 email: [email protected] Electronic comments can be mailed to: comments-pacificnorthwest- [email protected] i ABSTRACT On November 9, 2005, the Forest Service published final travel management regulations in the Federal Register (FR Vol. 70, No. 216-Nov. 9, 2005, pp 68264- 68291) (Final Rule). The final rule revised regulations 36 CFR 212, 251, 261 and 295 to require national forests and grasslands to designate a system of roads, trails and areas open to motor vehicle use by class of vehicle and, if appropriate, time of year. -

The Siskiyou Hiker 2020

WINTER 2020 THE SISKIYOU HIKER Outdoor news from the Siskiyou backcountry SPECIAL ISSUE: 2020 Stewardship Report Photo by: Trevor Meyer SEASON UPDATES ALL THE TRAILS CLEARED THIS YEAR LOOKING AHEAD CHECK OUT OUR Laina Rose, 2020 Crew Leader PLANS FOR 2021 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Winter, 2020 Dear Friends, In this special issue of the Siskiyou Hiker, we’ve taken our annual stewardship report and wrapped it up into a periodical for your review. Like everyone, 2020 has been a tough year for us. But I hope this issue illustrates that this year was a challenge we were up for. We had to make big changes, including a hiring freeze on interns and seasonals. My staff, board, our volun- teers, and I all had to flex into what roles needed to be filled, and far-ahead planning became almost impossi- ble. But we were able to wrap up technical frontcountry projects in the spring, and finished work on the Briggs Creek Bridge and a long retaining wall on the multi-use Taylor Creek Trail. Then my staff planned for a smaller intern program that was stronger beyond measure. We put practices in place to keep everyone safe, and got through the year intact and in good health. This year we had a greater impact on the lives of the young people who serve on our Wilderness Conserva- tion Corps. They completed media projects and gained technical skills. Everyone pushed themselves and we took the first real steps in realizing greater diversity throughout our organization. And despite protocols in place to slow the spread of Covid-19, we actually grew our volunteer program. -

Summary of Public Comment, Appendix B

Summary of Public Comment on Roadless Area Conservation Appendix B Requests for Inclusion or Exemption of Specific Areas Table B-1. Requested Inclusions Under the Proposed Rulemaking. Region 1 Northern NATIONAL FOREST OR AREA STATE GRASSLAND The state of Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Boise, ID - #6033.10200) Roadless areas in Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Inventoried and uninventoried roadless areas (including those Multiple ID, MT encompassed in the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act) (Individual, Bemidji, MN - #7964.64351) Roadless areas in Montana Multiple MT (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Pioneer Scenic Byway in southwest Montana Beaverhead MT (Individual, Butte, MT - #50515.64351) West Big Hole area Beaverhead MT (Individual, Minneapolis, MN - #2892.83000) Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, along the Selway River, and the Beaverhead-Deerlodge, MT Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, at Johnson lake, the Pioneer Bitterroot Mountains in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Great Bear Wilderness (Individual, Missoula, MT - #16940.90200) CLEARWATER NATIONAL FOREST: NORTH FORK Bighorn, Clearwater, Idaho ID, MT, COUNTRY- Panhandle, Lolo WY MALLARD-LARKINS--1300 (also on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest)….encompasses most of the high country between the St. Joe and North Fork Clearwater Rivers….a low elevation section of the North Fork Clearwater….Logging sales (Lower Salmon and Dworshak Blowdown) …a potential wild and scenic river section of the North Fork... THE GREAT BURN--1301 (or Hoodoo also on the Lolo National Forest) … harbors the incomparable Kelly Creek and includes its confluence with Cayuse Creek. This area forms a major headwaters for the North Fork of the Clearwater. …Fish Lake… the Jap, Siam, Goose and Shell Creek drainages WEITAS CREEK--1306 (Bighorn-Weitas)…Weitas Creek…North Fork Clearwater. -

Elliott State Forest: Next Step Considerations for Decoupling From

ELLIOTT STATE FOREST Next Step Considerations for Decoupling from Oregon’s Common School Fund October 2018 An Oregon Consensus Assessment Report to the Oregon Department of State Lands and Oregon State Land Board 1 Assessment Team Peter Harkema, Oregon Consensus Director Brett Brownscombe, Senior Project Manager Amy Delahanty, Project Associate Acknowledgements Oregon Consensus deeply appreciates all those who generously gave their time to inform this assessment and report. About Oregon Consensus Oregon Consensus (OC) was established by state statute as the State of Oregon's program for public policy conflict resolution and collaborative governance. The program provides mediation and other collaborative services to public bodies and stakeholders who are seeking new approaches to challenging public issues. OC conducts assessments and designs and facilitates impartial and transparent collaborative processes that foster balanced participation and durable agreements. OC is housed in the National Policy Consensus Center in the Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University. Contact Oregon Consensus National Policy Consensus Center Hatfield School of Government Portland State University 506 SW Mill Street, Room 720 PO Box 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 (503) 725-9077 [email protected] www.oregonconsensus.org 2 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Purpose of report .............................................................................................................................................. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Homelessness in the Willamette National Forest: a Qualitative Research Project

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank Homelessness in the Willamette National Forest: A Qualitative Research Project JUNE 2012 Prepared by: MASTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION CAPSTONE TEAM Heather Bottorff Tarah Campi Serena Parcell Susannah Sbragia Prepared for: U.S. Forest Service APPLIED CAPSTONE PRO JECT MASTER OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Long-term camping by homeless individuals in Western Oregon’s Willamette National Forest results in persistent challenges regarding resource impacts, social impacts, and management issues for the U.S. Forest Service. The purpose of this research project is to describe the phenomenon of homelessness in the Willamette National Forest, and suggest management approaches for local Forest Service staff. The issues experienced in this forest are a reflection of homelessness in the state of Oregon. There is a larger population of homeless people in Oregon compared to the national average and, of that population, a larger percentage is unsheltered (EHAC, 2008). We draw upon data from 27 qualitative interviews with stakeholders representing government agencies, social service agencies, law enforcement, homeless campers, and out-of- state comparators, including forest administrators in 3 states. Aside from out-of-state comparators, all interviews were conducted with stakeholders who interface with the homeless population in Lane County or have specific relevant expertise. Each category of interviews was chosen based on the perspectives the subjects can offer, such as demographics of homeless campers, potential management approaches, current practices, impacts, and potential collaborative partners. Our interviews suggest that there are varied motivations for long-term camping by homeless people in the Willamette National Forest. -

Download Chapter

Table Of Contents Conservation Toolbox............................................................................................................................... 3 Outreach, Education, and Engagement................................................................................................... 4 Voluntary Conservation Programs......................................................................................................... 16 Conservation in Urban Areas.................................................................................................................. 23 Planning and Regulatory Framework..................................................................................................... 30 General References.................................................................................................................................. 50 Conservation Toolbox Everyone has a role in the successful implementation of the Oregon Conservation Strategy. The Conservation Toolbox provides recommendations to support implementation and suggestions for additional information and assistance. Key components of the Conservation Toolbox include: Outreach, Education, and Engagement Conservation in Urban Areas Oregon’s Existing Planning and Regulatory Framework Voluntary Conservation Programs General References: additional resources outside of the references provided in each section Outreach, Education, and Engagement Connecting people to nature is an important element of successful Conservation Strategy implementation. Acquiring