The Alluvial Records of Buckskin Wash, Utah Jonathan E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) Depository) 11-19-2004 Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement Bureau of Land Management Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Bureau of Land Management, "Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area, Wildlife Habitat Improvement" (2004). All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository). Paper 77. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/77 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bureau of Land Management Phone 435.644.4300 Grand Staircase-Escalante NM 190 E. Center Street Fax 435.644.4350 Kanab, UT 84741 Landscape Assessment for the Buckskin Mountain Area Wildlife Habitat Improvement Version: 19 November 2004 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................... 3 A. Background and Need for Management Activity ................................................................... 3 B. Purpose ..................................................................................................................................... -

PRELUDE to SEVEN SLOTS: FILLING and SUBSEQUENT MODIFICATION of SEVEN BROAD CANYONS in the NAVAJO SANDSTONE, SOUTH-CENTRAL UTAH by David B

PRELUDE TO SEVEN SLOTS: FILLING AND SUBSEQUENT MODIFICATION OF SEVEN BROAD CANYONS IN THE NAVAJO SANDSTONE, SOUTH-CENTRAL UTAH by David B. Loope1, Ronald J. Goble1, and Joel P. L. Johnson2 ABSTRACT Within a four square kilometer portion of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, seven distinct slot canyons cut the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone. Four of the slots developed along separate reaches of a trunk stream (Dry Fork of Coyote Gulch), and three (including canyons locally known as “Peekaboo” and “Spooky”) are at the distal ends of south-flowing tributary drainages. All these slot canyons are examples of epigenetic gorges—bedrock channel reaches shifted laterally from previous reach locations. The previous channels became filled with alluvium, allowing active channels to shift laterally in places and to subsequently re-incise through bedrock elsewhere. New evidence, based on optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) ages, indicates that this thick alluvium started to fill broad, pre-existing, bedrock canyons before 55,000 years ago, and that filling continued until at least 48,000 years ago. Streams start to fill their channels when sediment supply increases relative to stream power. The following conditions favored alluviation in the study area: (1) a cooler, wetter climate increased the rate of mass wasting along the Straight Cliffs (the headwaters of Dry Fork) and the rate of weathering of the broad outcrops of Navajo and Entrada Sandstone; (2) windier conditions increased the amount of eolian sand transport, perhaps destabilizing dunes and moving their stored sediment into stream channels; and (3) southward migration of the jet stream dimin- ished the frequency and severity of convective storms. -

Paria Canyon Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Management Plan

01\16• ,.J ~ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR -- BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ~Lf 1.,.J/ t'CI/C w~P 0 ARIZONA STRIP FIELD OFFICE/KANAB RESOURCE AREA PARIA CANYONNERMILION CLIFFS WILDERNESS MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA-AZ-01 0-97-16 I. INTRODUCTION The Paria Canyon - Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area contains 112,500 acres (92,500 acres in Coconino County, Arizona and 20,000 acres in Kane County, Utah) of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The area is approximately 10 to 30 miles west of Page, Arizona. Included are 35 miles of the Paria river Canyon, 15 miles of the Buckskin Gulch, Coyote Buttes, and the Vermilion Cliffs from Lee's Ferry to House Rock Valley (Map 1). The Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch, Wire Pass, and the Coyote Buttes Special Management Area are part of the larger Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness, designated in August 1984 (Map 2). Existing management plan guidance is to protect primitive, natural conditions and the many outstanding opportunities for hiking, backpacking, photographing, or viewing in the seven different highly scenic geologic formations from which the canyons and buttes are carved. Visitor use in Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch, and Coyote Buttes has increased from 2,400 visits in Fiscal Year (FY) 1986 to nearly 10,000 visits in FY96-a 375% increase in use over 10 years. This increased use, combined with the narrow nature of the canyons, small camping terraces, and changing visitor use patterns, is impacting the wilderness character of these areas. Human waste, overcrowding, and public safety have become important issues. -

Directions to Hiking to Coyote Buttes & the Wave

Coyote Buttes/The Waves Ron Ross December 22, 2007 Coyote Buttes is located in the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness just south of US¶89 about halfway between Kanab, Utah and Page, Arizona. The wilderness area sits on the border between Arizona and Utah and is managed by the BLM. It is divided into two areas: Coyote Buttes North and Coyote Buttes South. To visit either of the Coyote Buttes areas you will need to purchase a hiking permit in advance (see https://www.blm.gov/az/paria/index.cfm?usearea=CB). Only 20 people per day (10 advanced reservations and 10 walk-ins) are allowed to hike in, and separate permits are required for the North and South sections. The walk-in permits can be acquired off the web, from the BLM office in Kanab, or from the Paria Ranger Station near the Coyote Buttes. The Northern section of Coyote Buttes is by far the most popular, as it contains the spectacular sandstone rock formations, pictured below, known as the Wave and the Second Wave. As a result of their popularity, getting permits for the Northern section is very competitive and often results in a lottery to select the lucky folks for a particular day. The Southern section also contains some outstanding sandstone formations known as the Te- pees. However, the road to the southern section can be very sandy and challenging, even for high- clearance 4x4 vehicles. As a result, walk-in permits for the Southern section are widely available. COYOTE BUTTES NORTH—THE WAVE Trailhead The hike to the wave begins at the Wire Pass Trailhead about 8 miles south of US¶89 on House Rock Valley Road. -

Slot Canyons of Dry Fork, Kane County

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences of 2019 Cut, Fill, Repeat: Slot Canyons of Dry Fork, Kane County David Loope University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Loope, David, "Cut, Fill, Repeat: Slot Canyons of Dry Fork, Kane County" (2019). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 616. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/616 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cut, Fill, Repeat: Slot Canyons of Dry Fork, Kane County David B. Loope Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, University of Nebraska Lincoln, NE 68588-0340 [email protected] Utah Geosites 2019 Utah Geological Association Publication 48 M. Milligan, R.F. Biek, P. Inkenbrandt, and P. Nielsen, editors Cover Image: Exploring a southern Utah slot canyon. Photo by Jim Elder. M. Milligan, R.F. Biek, P. Inkenbrandt, and P. Nielsen, editors 2019 Utah Geological Association Publication 48 Presidents Message I have had the pleasure of working with many diff erent geologists from all around the world. As I have traveled around Utah for work and pleasure, many times I have observed vehicles parked alongside the road with many people climbing around an outcrop or walking up a trail in a canyon. -

HPDP Summer Hiking Series Wire Pass to Buckskin Gulch Saturday, May 18Th, 2019 @ 7:30 AM (DST)

HPDP Summer Hiking Series Wire Pass TO Buckskin Gulch Saturday, May 18th, 2019 @ 7:30 AM (DST) Transportation: Please Note: Transportation to the hiking location will not be provided by TCRHCC or Health Promotion Diabetes Prevention (HPDP). We kindly encourage participants to drive in their own vehicles or carpool with other participants. Road Condition: Dirt road, washboard, rough, some mud spots. Car Accessible in Dry Weather Only. Travel Time: 2.5 Hours from Tuba City- Please plan ahead, drive safely. Do not leave any later than 5:15 AM DST from Tuba City. Physical Fitness Requirements: Must have the lower body strength - to ascend & descend steep hills. * Children (8-12yo) are welcome to hike this trail (parent must be with children at all times) *If you have any joint problems/knee problems, this hike may not be suitable for you. There are spots along hike where it is very steep. Hiking Event Site Information: Hiking Time: 2 - 4 Hours – All HPDP hikes are ONE DAY. Distance: ~ 3.4 miles, Round Trip Trail Elevation Change: No considerable elevation change. Trail Rating: Moderate - Hard Trail: River Wash Route, Single Person, Slot Canyons, 8-10 Foot Drop in Close Quarters. Bring own snacks and meal. Restroom: There are restrooms available at the Wire Pass trailhead. PLEASE bring a trash bag to properly dispose of tissue/trash used on the trail. DO NOT leave any trash behind on the trail. How to prepare for the hike: 1. Always get a good night of rest before the hike. 2. Hydrate and eat a full meal the day before and day of the hike; everyone is required to carry their own water. -

Exploring Utah's Zebra Canyon a Free Excerpt from the Best Grand

Exploring Utah’s Zebra Canyon A free excerpt from The Best Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Hikes By Sarah Pultorak Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in south-central Utah is one of the most secluded areas in the nation. The region’s bare-bones desert landscape is marked with towering geologic formations that leave everyone, from day trippers to seasoned desert rats, astonished. The sedimentary rock which makes up the foundation of the Colorado Plateau, upon which the monument sits, is a massive outdoor museum. It showcases eons of desert life and detailed tectonic history dating back as far as 98 million years. This rugged past has resulted in impressive cliffs, daunting towers and arches, deep canyons, and powerful rivers, all of which make the area a mecca for outdoor adventure. Despite President Trump’s 2017 proclamation that reduced the overall size of the monument by 47 percent, the protected sections still cover over a million acres of public lands – an area so remote that it was the last portion of the contiguous United States to be mapped. The newest guidebook from Colorado Mountain Club Press, The Best Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Hikes, highlights 25 of the region’s can’t-miss trails. Just in time for desert season, this upcoming release from authors Morgan Sjogren (The Best Bears Ears National Monument Hikes, Outsider) and Michael VerSteeg includes hikes within the monument’s current and former boundaries – and it’s the only guide with information up to date as of late 2019. Here’s a free chapter excerpt by Sjogren and VerSteeg featuring one of the most popular hikes in the new pack guide: Zebra Canyon. -

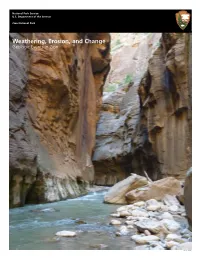

Erosion, Weathering, and Change Activity Guide

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Zion National Park Weathering, Erosion, and Change Geologic Events in Zion PHOTO CREDIT Contents Introduction 2 Core Connections 2 Background 2 Activities Earth’s Power Punches 4 Rock On, Zion 5 It Happened Here! 6 Glossary 8 References 9 Introduction This guide contains background information about how weathering, erosion, and other geologic processes such as volcanoes continually shape the landscape, and directions for three activities that will help students better understand how these processes are at work in Utah. This guide is specifically designed for fifth grade classrooms, but the activities can be NPS modified for students at other levels. Theme of deposition (sedimentation), lithification, The Earth’s surface is a dynamic system that is uplift, weathering, erosion, tectonics, and constantly changing due to weathering, volcanic activity make the park a showcase for erosion, floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, and changing landscapes. other geologic events. Deposition (Sedimentation) Focus Zion National Park was a relatively flat basin The activities focus on relationship between near sea level 275 million years ago, near the NPS/MARC NEIDIG geologic processes such as weathering and coast of Pangaea, the land area believed to erosion and changes on the Earth’s surface. have once connected nearly all of the earth’s landmasses together. As sands, gravels, and Activities muds eroded from surrounding mountains, Earth’s Power Punches streams carried these materials into the Students view a presentation of digital im- basin and deposited them in layers. The sheer ages showing the forces that shape the Earth’s weight of these accumulated layers caused surface. -

Discover American Canyonlands - NUVNG

Privacy Notice: We use technologies on our website for personalizing content, advertising, providing social media features, and analyzing our traffic. We also share information about your use of our site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners. By continuing to use this website, you consent to our use of this technology. You can control this through your Privacy Options. Accept Last Updated: June 8, 2021 Discover American Canyonlands - NUVNG 8 days: Las Vegas to Las Vegas What's Included • Your Journeys Highlight Moment: Grand Canyon Exclusive, Grand Canyon National Park • Your Journeys Highlight Moment: Lowell Observatory Experience, Flagstaff • Your G for Good Moment: Native Grill Food Truck • All national park fees • Zion National Park visit and guided hike • Bryce Canyon National Park visit • Antelope Canyon guided visit • Horseshoe Bend hike • Grand Canyon National Park visit • Route 66 stop • All transport between destinations and to/from included activities The information in this trip details document has been compiled with care and is provided in good faith. However it is subject to change, and does not form part of the contract between the client and G Adventures. The itinerary featured is correct at time of printing. It may differ slightly to the one in the brochure. Occasionally our itineraries change as we make improvements that stem from past travellers, comments and our own research. Sometimes it can be a small change like adding an extra meal along the itinerary. Sometimes the change may result in us altering the tour for the coming year. Ultimately, our goal is to provide you with the most rewarding experience. -

Canyons of the Southwest Bryce Canyon Zion National Park Grand Canyon National Park Vermillion Cliffs Lake Powell

Canyons of the Southwest Bryce Canyon Zion National Park Grand Canyon National Park Vermillion Cliffs Lake Powell 8 days/ 7 nights Costs based on minimum 4 guests. Endless cliffs, red hills and open skies define this area. It is a hikers paradise and with a professional guide, your experience is augmented further with their deep knowledge in paleontology, geology, flora and fauna. Accommodations are a mix of hotels and as well as a luxury tented facility. Canyons of the Southwest This trip can be experienced with a full-time guide and vehicle or self-drive. Refer to the pricing tab. Day 1: Arrive into St. George Fully Guided: Upon arrival into the St. George Regional Airport, your Guide will pick you up. Self-Drive: Pick up your rental car upon arrival (paid directly) Transfer you to your accommodations (approximately 1.5 hours). The Ranch It is the closest to Zion National Park lodging option and from there you can see several area national parks including Bryce Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon and more. Zion Mountain Ranch (no meals) Day 2: Bryce Canyon National Park Today your expert Guide will take you to Bryce Canyon National Park for a half-day privately guided hike. Spend time in the two largest amphitheaters in Bryce Canyon, hiking into the maze of hoodoos that make Bryce a unique experience. Trail selection will be based on how everyone feels, and your interest in strenuous vs. easy hiking. You'll hike 2 to 6 miles and then take in some of the great viewpoints along the 17-mile scenic drive further south on the Paunsaugunt Plateau including Bryce Point, Sunrise Point, and Sunset Point. -

Paria Canyon Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ARIZONA STRIP FIELD OFFICE/KANAB RESOURCE AREA DECISION RECORD DR-AZ-010-98-03 MANAGEMENT OF RECREATION IN THE PARIA CANYON - VERMILION CLIFFS WILDERNESS The Paria Canyon - Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area contains 112,500 acres of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The area is approximately 10 to 30 miles west of Page, Arizona. Included are 35 miles of the Paria River Canyon, 15 miles of the Buckskin Gulch, Coyote Buttes, and the Vermilion Cliffs from Lee's Ferry to House Rock Valley. The Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch, Wire Pass, and the Coyote Buttes Special Management Area are part of the larger Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness, designated in August 1984. Visitor use has increased from 2,400 visits in Fiscal Year (FY) 1986 to nearly 10,000 visits in FY96-a 375% increase in use over 10 years. This increased use, combined with the narrow nature of the canyons, small camping terraces, and changing visitor use patterns, is impacting the wilderness character of these areas. Human waste, overcrowding, and public safety have become significant issues. The purpose of this action is to establish guidelines and implement management actions related to recreational use of the Paria CanyonNermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area. An increase in recreational use in the wilderness has caused degradation of sensitive resources. On pag~ 8, the plan states that BLM will "initiate a system to regulate recreation use if monitoring demonstrates a need to limit user numbers. A study of alternative a/location techniques, including fees, will be prepared and analyzed in an environmental assessment involving public participation. -

The Geology of Zion

National Park Service Zion U.S. Department of the Interior Zion National Park The Geology of Zion Grand Canyon Bryce Canyon Zion Canyon Kaibab Plateau Pink Cliffs South Rim North Rim Vermilion Cliffs Grand Canyon Grand Canyon White Cliffs Chocolate Cliffs Gray Cliffs The Grand Staircase Zion is located along the edge of a region called the Colorado Plateau. Uplift, tilting, and erosion of rock layers formed a feature called the Grand Staircase, a series of colorful cliffs stretching between Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon. The bottom layer of rock at Bryce Canyon is the top layer at Zion, and the bottom layer at Zion is the top layer at the Grand Canyon. The Geologic Story Zion National Park is a showcase of geology. The arid Uplift climate and sparse vegetation expose bare rock and In an area from Zion to the Rocky Mountains, forces reveal the park’s geologic history. deep within the earth started to push the surface up. This was not chaotic uplift, but slow vertical hoist- Sedimentation ing of huge blocks of the crust. Zion’s elevation rose Zion was a relatively fl at basin near sea level 275 mil- from near sea level to as high as 10,000 feet above sea lion years ago. As sands, gravels, and muds eroded level. from surrounding mountains, streams carried these materials into the basin and deposited them in layers. Uplift is still occurring. In 1992 a magnitude 5.8 The sheer weight of these accumulated layers caused earthquake caused a landslide visible just outside the the basin to sink, so that the top surface always south entrance of the park.