Clarence King & His Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

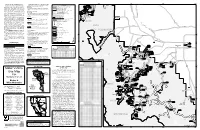

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

Motor Vehicle Use

350000 360000 370000 380000 118°45'0"W 30E301A 118°37'30"W Continued on Casa Diablo Map 118°30'0"W 118°22'30"W T OPERATOR RESPONSIBILITIES EXPLANATION OF LEGEND ITEMS 04S15B o PINE GROVE 04S15 M Legend PICNIC AREA 3 04S15E a 0 Operating a motor vehicle on National Forest System Roads Open to Highway Legal Vehicles Only: m " LOWER E m Roads Open to Highway Legal Vehicles 5" 3 roads, National Forest System trails, and in areas on 04S15C 9 & 0 o 1 UPPER t PINE h National Forest System lands carries a greater These roads are open only to motor vehicles licensed under Roads Open to All Vehicles 04S18 " 2 9 0 GROVE 3 responsibility than operating that vehicle in a city or other State law for general operation on all public roads within the 04S18B E Trails Open to All Vehicles CAMPGROUND 0 developed setting. Not only must you know and follow all State. 3 applicable traffic laws, you need to show concern for the Trails Open to Vehicles 50" or Less in Width 04S12O 04S18A environment as well as other forest users. The misuse of Roads Open to All Vehicles: ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Trails Open to Motorcycles Only 06S08 0 6 motor vehicles can lead to the temporary or permanent S 06S08A G Rock 0 04S12P o Seasonal Designation 6 r closure of any designated road, trail, or area. As a motor These roads are open to all motor vehicles, including smaller 9" Creek g (See Seasonal Designation Table) e 04S12Q vehicle operator, you are also subject to State traffic law, off-highway vehicles that may not be licensed for highway Lake R d including State requirements for licensing, registration, and use (but not to oversize or overweight vehicles under State Highways, US, State 9" 06S06A MOSQUITO FLAT operation of the vehicle in question. -

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Frontispiece the 1864 Field Party of the California Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC ROAD GUIDE TO KINGS CANYON AND SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARKS, CENTRAL SIERRA NEVADA, CALIFORNIA By James G. Moore, Warren J. Nokleberg, and Thomas W. Sisson* Open-File Report 94-650 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. * Menlo Park, CA 94025 Frontispiece The 1864 field party of the California Geological Survey. From left to right: James T. Gardiner, Richard D. Cotter, William H. Brewer, and Clarence King. INTRODUCTION This field trip guide includes road logs for the three principal roadways on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada that are adjacent to, or pass through, parts of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (Figs. 1,2, 3). The roads include State Route 180 from Fresno to Cedar Grove in Kings Canyon Park (the Kings Canyon Highway), State Route 198 from Visalia to Sequoia Park ending near Grant Grove (the Generals Highway) and the Mineral King road (county route 375) from State Route 198 near Three Rivers to Mineral King. These roads provide a good overview of this part of the Sierra Nevada which lies in the middle of a 250 km span over which no roads completely cross the range. The Kings Canyon highway penetrates about three-quarters of the distance across the range and the State Route 198~Mineral King road traverses about one-half the distance (Figs. -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

1911-1912 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

Ji UNI\fc.RSJTY OBITUARY RECORD OF YALE GRADUATES PUBLISHED By THE UNIVERSITY NEW HAVEN Eighth Series No 9 July 1912 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Entered as second-class matter, August 30, 1906, at the post- office at New Haven, Conn , under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894. The Bulletin, which is issued monthly, includes : 1. The University tatalogue. 2 The Reports of the President, Treasurer, and Librarian 3. The Pamphlets of the Several Departments. 1 THE TU1TLE, MOREHOUSE 4 TAYI OK COMPANY, NEW HAVEN, CONN OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE MYERSITY Deceased during the year endingf JUNE 1, 1912, INCLUDING THE RECORD OF A FEW WHO DIED PREVIOUSLY HITHERTO UNREPORTED [No 2 of the Sixth Printed Series, and So 71 of the whole Record The present Series •will consist of fi\e numbers ] OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the year ending JUNE I, 1912, Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [No 2 of the Sixth Printed Series, and No 71 of the whole Record The present Series will consist of five numbers ] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1838 HENRY PARSONS HEDGES, third of four sons and fourth of the six children of Zephaniah and Phebe P (Osborn) Hedges, was born at Wamscott in East Hampton, Long Island, N Y, October 13, 1817 His grandfather, Deacon David Hedges, was a member of the Colonial Congress at Kingston, N. Y, and a member of the Constitutional Con- vention of the State of New York which ratified the constitution of the United States Since the death of his classmate, Chester Dutton, July 1, 1909, he had been the oldest living graduate of the University He was the last survivor of his class He attended the Yale Commencement exercises in 1910, and made an addiess at the Alumni Meetmg, and was also an honored guest in 1911 He was fitted for college at Clinton Academy, East Hampton, and entered his class in college Sophomore year After graduation he spent a year at home and a year in the Yale Law School, and then continued his law studies I66 YALE COLLEGE with Hon David L. -

Boyhood Days in the Owens Valley 1890-1908

Boyhood Days in the Owens Valley 1890-1908 Beyond the High Sierra and near the Nevada line lies Inyo County, California—big, wild, beautiful, and lonely. In its center stretches the Owens River Valley, surrounded by the granite walls of the Sierra Nevada to the west and the White Mountains to the east. Here the remote town of Bishop hugs the slopes of towering Mount Tom, 13,652 feet high, and here I was born on January 6, 1890. When I went to college, I discovered that most Californians did not know where Bishop was, and I had to draw them a map. My birthplace should have been Candelaria, Nevada, for that was where my parents were living in 1890. My father was an engineer in the Northern Belle silver mine. I was often asked, "Then how come you were born in Bishop?" and I replied, "Because my mother was there." The truth was that after losing a child at birth the year before, she felt Candelaria's medical care was not to be trusted. The decline in the price of silver, the subsequent depression, and the playing out of the mines in Candelaria forced the Albright family to move to Bishop permanently. We had a good life in Bishop. I loved it, was inspired by its aura, and always drew strength and serenity from it. I have no recollection of ever having any bad times. There weren't many special things to do, but what- ever we did, it was on horseback or afoot. Long hours were spent in school. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

22–25 Oct. GSA 2017 Annual Meeting & Exposition

22–25 Oct. GSA 2017 Annual Meeting & Exposition JULY 2017 | VOL. 27, NO. 7 NO. 27, | VOL. 2017 JULY A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA® JULY 2017 | VOLUME 27, NUMBER 7 SCIENCE 4 Extracting Bulk Rock Properties from Microscale Measurements: Subsampling and Analytical Guidelines M.C. McCanta, M.D. Dyar, and P.A. Dobosh GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news Cover: Mount Holyoke College astronomy students field-testing a and information for more than 26,000 GSA member readers and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (March/ Raman BRAVO spectrometer for field mineral identification, examin- April is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The ing pegmatite minerals crosscutting a slightly foliated hornblende Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at quartz monzodiorite and narrow aplite dikes exposed in the spillway 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- of the Quabbin Reservoir. All three units are part of the Devonian ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation Belchertown igneous complex in central Massachusetts, USA. of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, See related article, p. 4–9. regardless of race, citizenship, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. © 2017 The Geological Society of America Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright not claimed on content prepared GSA 2017 Annual Meeting & Exposition wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted 11 Abstracts Deadline permission, without fees or request to GSA, to use a single figure, table, and/or brief paragraph of text in subsequent 12 Education, Careers, and Mentoring work and to make/print unlimited copies of items in GSA TODAY for noncommercial use in classrooms to further 13 Feed Your Brain—Lunchtime Enlightenment education and science. -

Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks

S o k u To Bishop ee t Piute Pass Cr h F 11423ft p o o 3482m r h k s S i o B u B i th G s h L o A p Pavilion Dome Mount C F 11846ft IE Goethe C or r R e k S 3611m I 13264ft a D VID e n 4024m k E J Lake oa q Sabrina u McClure Meadow k r i n 9600ft o F 2926m e l d R d Mount Henry i i Mount v 12196ft e Darwin M 3717m r The Hermit 13830ft South L 12360ft 4215m E 3767m Lake Big Pine C G 3985ft DINKEY O O 1215m O P D Hell for Sure Pass E w o N D Mount V s 11297ft A O e t T R McGee n L LAKES 3443m D U s E 12969ft T 3953m I O C C o A N r N Mount Powell WILDERNESS r D B a Y A JOHN l 13361ft I O S V I R N N 4072m Bi Bishop Pass g P k i ine Cree v I D e 11972ft r E 3649m C Mount Goddard L r E MUIR e 13568ft Muir Pass e C DUSY North Palisade k 4136m 11955ft O BASIN 3644m N 14242ft Black Giant T E 4341m 13330ft COURTRIGHT JOHN MUIR P Le Conte A WILDERNESS 4063m RESERVOIR L I Canyon S B Charybdis A 395 8720ft i D rc 13091ft E Middle Palisade h 2658m Mount Reinstein 14040ft 3990m C r WILDERNESS CR Cre e 12604ft A ek v ES 4279m i Blackcap 3842m N T R Mountain Y O an INYO d s E 11559ft P N N a g c r i 3523m C ui T f n M rail i i H c John K A e isad Creek C N Pal r W T e E s H G D t o D I T d E T E d V r WISHON G a a IL O r O S i d l RESERVOIR R C Mather Pass Split Mountain G R W Finger Pe ak A Amphitheater 14058ft E 12100ft G 12404ft S Lake 4285m 3688m E 3781m D N U IV P S I C P D E r E e R e k B C A SIERRA NATIONAL FOREST E art Taboose r S id G g k e I N Pass r k Tunemah Peak V D o e I 11894ft 11400ft F e A R r C 3625m ree 3475m C k L W n L k O Striped -

![Yosemite National Park [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4323/yosemite-national-park-pdf-1784323.webp)

Yosemite National Park [PDF]

To Carson City, Nev il 395 ra T Emigrant Dorothy L ake Lake t s Bond re C Pass HUMBOLDT-TOIYABE Maxwell NATIONAL FOREST S E K Lake A L c i f i c IN a Mary TW P Lake Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Lake Buckeye Pass Huckleberry Twin Lakes 9572 ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS Lake 2917 m HO O k N e V e O E r Y R C N Peeler A W Lake Crown C I Lake L D Haystack k e E Peak e S R r A Tilden W C TO N Schofield OT Rock Island H E Lake R Peak ID S Pass G E S s Styx l l Matterhorn Pass a F Peak Slide Otter ia Mountain Lake r e Burro h Green c Pass D n Many Island Richardson Peak a Lake L Lake 9877 ft R (summer only) IE 3010 m F E L Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k A e a ic L r C e Kibbie N r d YO N C Lake n N A I C e ACK A RRICK J M KE ia K in N rg I i A r V T e l N k l i U e e p N O r C S M O Lundy Lake Y L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541 ft iu A T P L C I 3213 m T (summer only) Smedberg Benson k Lake e Pass k e e r e C r Benson C Lake k Lake ee Cree r Vernon k C r o e Upper n Volunteer cCab a M e McCabe l Mount Peak E Laurel k n r Lake Lake Gibson e u e N t r e McC C a R b R e L R a O O A ke Rodgers I s N PLEASANT A E H N L Lake I k E VALLEY R l Frog e i E k G K e E e a LA r R e T I r C r Table Lake V T T North Peak C Pettit Peak N A 10788 ft INYO NATIONAL FOREST O Y 3288 m M t ls Saddlebag al N s Roosevelt F A e Lake TIL a r Lake TILL ri C VALLEY (summer only) e C l h Lake Eleanor il c ilt n Mount Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S Conness R I Virginia c HALL -

Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Rock Falls in Yosemite Valley, California by Gerald F. Wieczorek1, James B. Sn

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ROCK FALLS IN YOSEMITE VALLEY, CALIFORNIA BY GERALD F. WIECZOREK1, JAMES B. SNYDER2, CHRISTOPHER S. ALGER3, AND KATHLEEN A. ISAACSON4 Open-File Report 92-387 This work was done with the cooperation and assistance of the National Park Service, Yosemite National Park, California. This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government 'USGS, Reston, VA 22092, 2NPS, Yosemite National Park, CA, 95389, 3McLaren/Hart, Alameda, CA 94501, 4Levine Fricke, Inc., Emeryville, CA 94608 Reston, Virginia December 31, 1992 CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................... 1 Introduction .............................................. 1 Geologic History ........................................... 2 Methods of Investigation ..................................... 5 Inventory of historical slope movements ........................ 5 Location ............................................ 5 Time of occurrence .......:............................ 7 Size ............................................... 8 Triggering mechanisms ................................. 9 Types of slope movement ................................ 11 Debris flows ...................................... 11 Debris slides ...................................... 12 Rock slides ......................................