Water Management Plan 2020-21: Chapter 3.12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborginal and Historic Gap Analysis and Future Direction Report Wilton

ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS Greater Macarthur Investigation Area Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy Final Department of Planning and Environment February 2017 Greater Macarthur Investigation Area Regional Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy i ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS Document Control Page Anita Yousif, Laressa Berehowyj and Fenella AUTHOR/HERITAGE ADVISOR Atkinson CLIENT Department of Planning and Environment Greater Macarthur Investigation Area: PROJECT NAME Archaeological Research Design and Management Strategy REAL PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Various EXTENT PTY LTD INTERNAL REVIEW/SIGN OFF WRITTEN BY DATE VERSION REVIEWED APPROVED Anita Yousif, Laressa Berehowyj and Fenella 31/09/2016 1 Draft Susan McIntyre- Atkinson Tamwoy Susan McIntyre- Anita Yousif, Laressa Tamwoy, Berehowyj and Fenella 10/10/2016 Final Alan Williams Updated Aboriginal Atkinson Draft heritage maps to be substituted once data has been received. Anita Yousif, Laressa Susan McIntyre- Susan McIntyre- Berehowyj and Fenella 3/02/2017 Final Tamwoy Tamwoy Atkinson Copyright and Moral Rights Historical sources and reference materials used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced in figure captions or in text citations. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners. Unless otherwise specified in the contract terms for this project EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD: Vests copyright of all material produced by EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD (but excluding pre-existing material and material in which copyright is held by a third party) in the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title); Retains the use of all material produced by EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD for this project for EXTENT HERITAGE PTY LTD ongoing business and for professional presentations, academic papers or publications. -

Murrumbidgee Regional Fact Sheet

Murrumbidgee region Overview The Murrumbidgee region is home The river and national parks provide to about 550,000 people and covers ideal spots for swimming, fishing, 84,000 km2 – 8% of the Murray– bushwalking, camping and bird Darling Basin. watching. Dryland cropping, grazing and The Murrumbidgee River provides irrigated agriculture are important a critical water supply to several industries, with 42% of NSW grapes regional centres and towns including and 50% of Australia’s rice grown in Canberra, Gundagai, Wagga Wagga, the region. Narrandera, Leeton, Griffith, Hay and Balranald. The region’s villages Chicken production employs such as Goolgowi, Merriwagga and 350 people in the area, aquaculture Carrathool use aquifers and deep allows the production of Murray bores as their potable supply. cod and cotton has also been grown since 2010. Image: Murrumbidgee River at Wagga Wagga, NSW Carnarvon N.P. r e v i r e R iv e R v i o g N re r r e a v i W R o l g n Augathella a L r e v i R d r a W Chesterton Range N.P. Charleville Mitchell Morven Roma Cheepie Miles River Chinchilla amine Cond Condamine k e e r r ve C i R l M e a nn a h lo Dalby c r a Surat a B e n e o B a Wyandra R Tara i v e r QUEENSLAND Brisbane Toowoomba Moonie Thrushton er National e Riv ooni Park M k Beardmore Reservoir Millmerran e r e ve r i R C ir e e St George W n i Allora b e Bollon N r e Jack Taylor Weir iv R Cunnamulla e n n N lo k a e B Warwick e r C Inglewood a l a l l a g n u Coolmunda Reservoir M N acintyre River Goondiwindi 25 Dirranbandi M Stanthorpe 0 50 Currawinya N.P. -

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

Your Candidates Metropolitan

YOUR CANDIDATES METROPOLITAN First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria Election 2019 “TREATY TO ME IS A RECOGNITION THAT WE ARE THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF THIS COUNTRY AND THAT OUR VOICE BE HEARD AND RESPECTED” Uncle Archie Roach VOTING IS OPEN FROM 16 SEPTEMBER – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Treaties are our self-determining right. They can give us justice for the past and hope for the future. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be our voice as we work towards Treaties. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be set up this year, with its first meeting set to be held in December. The Assembly will be a powerful, independent and culturally strong organisation made up of 32 Victorian Traditional Owners. If you’re a Victorian Traditional Owner or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person living in Victoria, you’re eligible to vote for your Assembly representatives through a historic election process. Your voice matters, your vote is crucial. HAVE YOU ENROLLED TO VOTE? To be able to vote, you’ll need to make sure you’re enrolled. This will only take you a few minutes. You can do this at the same time as voting, or before you vote. The Assembly election is completely Aboriginal owned and independent from any Government election (this includes the Victorian Electoral Commission and the Australian Electoral Commission). This means, even if you vote every year in other elections, you’ll still need to sign up to vote for your Assembly representatives. Don’t worry, your details will never be shared with Government, or any electoral commissions and you won’t get fined if you decide not to vote. -

Exhibition Catalogue Message from Our Co-Chairs

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE MESSAGE FROM OUR CO-CHAIRS In 2019 we are celebrating 10 years of the Schools Reconciliation Challenge (SRC)! For 10 years Reconciliation NSW has been engaging young people and schools in reconciliation. Our theme this year, Speaking and Listening from the Heart has inspired primary and high school students from across NSW and the ACT to create reconciliation-inspired art and writing for the SRC. We continue to be inspired by the contribution these young people, from many different backgrounds, make to reconciliation with their talent and insight. We thank each and every school, teacher, principal, parent and student who has taken part, guided and supported students and each other. It is thanks to their dedication that the SRC continues to grow each year. We are grateful for their hard work and commitment in ensuring that schools are key contributors to reconciliation processes. In 2019 we received 415 art and writing entries from students across NSW and the ACT, each reflecting the theme and their perspectives on Australia’s ongoing reconciliation journey. It is a privilege to see the depth of engagement, insight and commitment to reconciliation in action that students demonstrate ACKNOWLEDGMENT through their art and writing entries. OF COUNTRY The quality of the art and writing entries we received made the selection process for the exhibition Reconciliation NSW hard work. Many of the artworks were developed acknowledges the collaboratively, involving classes or groups of students traditional owners of under the guidance of local Aboriginal artists, parents Country throughout and community members. We thank the panel of NSW and the ACT judges: Jody Broun, Fiona Petersen, Kirli Saunders, and recognises their Jane Waters, Annie Tennant, Yvette Poshoglian and continuing connections Fiona Britton for their time and expertise in selecting to land, waters and this year’s entries. -

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements

Extract from Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements NNTT number NIA1998/001 Short name Tumut Brungle Area Agreement ILUA type Area Agreement Date registered 21/06/1999 State/territory New South Wales Local government region Gundagai Shire Council, Tumbarumba Shire Council, Tumut Shire Council, Holbrook Shire Council, Wagga Wagga, Yarrowlumla Shire Council, Yass Shire Council Description of the area covered by the agreement The agreement covers an area of approximately 8500 sq km. It’s external boundary (described in detail below) runs approximately from Coolac on the Hume Highway east to Lake Burrinjuck (north east of Wee Jasper); south along the Brindabella and Fiery Ranges to near Yarrangobilly Caves on the Snowy Mountains Highway, south west to the Murray River near Tintaldra; then along the Murray River to Jingellic; and then generally north towards Gundagai and on to Coolac. Description of the area covered by the Agreement : Clause 1.1.2 of the agreement states: "Deed Area" - means the area of land set out in the plan `and description set out at Schedule 1. Schedule 1 of the agreement contains a gazettal notice of the constitution of the Brungle Tumut Local Aboriginal Land Council Area dated 2 February 1984, set out below: BRUNGLE TUMUT LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL AREA Commencing at the junction of the generally south-eastern boundary of the Parish of Jingellec East with the boundary between the States of New South Wales and Victoria: and bounded thence by the latter boundary generally south-easterly to the Tooma River; by that -

Regional Water Availability Report

Regional water availability report Weekly edition 7 January 2019 waternsw.com.au Contents 1. Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. System risks ............................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Climatic Conditions ............................................................................................................................... 4 4. Southern valley based operational activities ..................................................................................... 6 4.1 Murray valley .................................................................................................................................................... 6 4.2 Lower darling valley ........................................................................................................................................ 9 4.3 Murrumbidgee valley ...................................................................................................................................... 9 5. Central valley based operational activities ..................................................................................... 14 5.1 Lachlan valley ................................................................................................................................................ 14 5.2 Macquarie valley .......................................................................................................................................... -

Part 2 Taphoglyphs (Inhumation, "Carved Trees," Or Grave Indicators)

11 PAR'f H. TAPlIOGLYPHS (INHUMATION, "CARVED TREES," OR GP"AVE-INDICATORS). " In antiquity at least it is certain that trees were frequently planted around the barrows of the dead, and that leafy branches formed part of the funeral cerem.onies." 33 If wc substitute the words "caryed" or "incised" for planted, and "graves" for" barrows," the above quotation is just as applicable to certain communities of the Australian aborigines as it is to ancient and bygone lleoples. There is this difference hetween these taphoglyphs or burial-trees and the teleteglyphs, or Bora-trees, as Mr. Milne reminds me. The carvings on the first were invariably deeper, and evidently intended to be permanent, as compared with the average glyphs on the second. 1. OBJECT OF THE TAPHOGLYPHS. 1'hc precise significance attached to these incised tree-boles by the aborigines is now difficlllt .to conceive with certainty, but I think we may conclude Dr. John Fraser was correct in saying that in the main they were intended to indicate an interment, "presumedly acting the part of a tombstone."" Indeed, Mr. T. lIonery saict'" the Kamilaroi tribes cut figures on the trees round the graves as memorials of the dead. Not only were these carved boles memorials of the dead, but there appears to be fairly conclusive evidence that it was only notabilities who were so honoured at their demise, such as celebrated warriors, prominent headmen, and powerful wizards or " doctors." Ordinary tribesmen, women, and children were, presumably, without the pale."" From this it may be ll~ Grant Allen. 1I~ Fl'il~er-"Aborigines of New &uth \Yales, 1l_'World's Colllmbian Expos., Chicago (]S93), lS9"2, p. -

Deliverabiliy of Environmental Water in the Murray Valleyx

Deliverability of Environmental Water in the Murray Valley Report to Murray Group of Concerned Communities May 2012 Final Report Version: 3.0 Page 1 of 41 Citation Murray Catchment Management Authority (2012) Deliverability of Environmental Water in the Murray Valley. © 2012 Murray Catchment Management Authority This work is copyright. With the exception of the photographs, any logo or emblem, and any trademarks, the work may be stored, retrieved and reproduced in whole or part, provided that it is not sold or used for commercial benefit. Any reproduction of information from this work must acknowledge Murray Group of Concerned Communities, Murray Catchment Management Authority, or the relevant third party, as appropriate as the owner of copyright in any selected material or information. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) or above, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Murray Group of Concerned Communities or Murray Catchment Management Authority. Murray Group of Concerned Communities Disclaimer This report has been prepared for Murray Group of Concerned Communities and is made available for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion regarding the development of the Draft Murray Darling Basin Plan. The opinions, comments and analysis (including those of third parties) expressed in this document are for information purposes only. This document does not indicate the Murray Group of Concerned Communities’ commitment to undertake or implement a particular -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

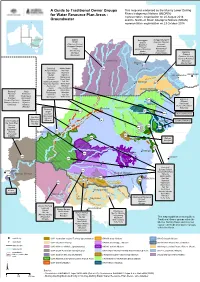

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

Mudjarn Nature Reserve

MUDJARN NATURE RESERVE PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Part of the Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW July 2008 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for Climate Change and the Environment on 21st July 2008. Acknowledgments This plan of management was prepared by staff of South West Slopes Region of NPWS (now the Parks and Wildlife Division of the Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW) with valuable assistance from the Brungle community. The Service would like to thank those members of the Brungle community who attended a series of community meetings to discuss the content and progress of this plan. Cover photograph: looking towards Mudjarn Nature Reserve by Jo Caldwell, DECC. Inquiries about Mudjarn Nature Reserve or this plan of management should be directed to the NPWS South West Slopes Region Office, 7a Adelong Rd, Tumut NSW 2720 or by telephone on 69477000. © Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 2008: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment ISBN 1 74122 250 8 FOREWORD Mudjarn Nature Reserve is located two kilometres south of Brungle and 15 kilometres north of Tumut on the South West Slopes of New South Wales. It consists of two parcels of land totalling 591 hectares and forms part of a broader fragmented native landscape in an otherwise heavily cleared environment. The reserve is also known locally as “Pine Mountain” due the locally abundant Black Cypress Pine (Callitris endlicherii), which gives the reserve a very dark appearance and makes it stand out from other high points in the area. Mudjarn Nature Reserve protects areas of remnant native forest, including small pockets of Yellow Box and Red Gum woodland, a component of the endangered White Box - Yellow Box - Blakely’s Red Gum woodland community.