CHAPTER 26 / Vital Sign Assessment 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment Module

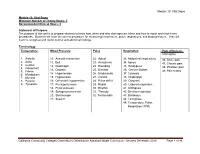

Assessment Module 1 | Page Assessment May 2017 Table of Contents About this Module/Overview/Objectives……………………………………………...Page 3 Pre-test…………………………………………………………………………………Pages 4-5 Chapter 1……………………………………………………………………………....Pages 6-12 Overview Focused Assessment vs. Comprehensive Assessment Considerations in preparing for a physical exam Geriatric Assessment Nursing Components Considerations in Elderly Residents Chapter 2……………………………………………………………………………...Pages 12-14 Root Cause of Behaviors Physiologic Social Environmental Psychosocial Chapter 3……………………………………………………………………………...Pages 14-16 Risk Assessment Eyes Ears Hemiparesis Paraplegia Where to place the resident in the room Chapter 4……………………………………………………………...………………Pages 16-18 Texas Board of Nursing and Assessments Federal Nursing Facility Regulations F272: Comprehensive Assessments State Nursing Facility Regulations Chapter 5………………………………………………………………………….......Pages 18-19 Resources “This is me” “This is me: My Care Passport” Alternate Communication Boards Pain, Pain Go Away Presentation Appendices……………………………………………………………………………Pages 20-48 2 | Page Assessment May 2017 About this Module: Assessment is a key component of nursing practice, required for planning and the provision of resident and family centered care. Information that is obtained from an accurate assessment serves as the foundation for age-appropriate nursing care, enhancing the residents’ quality of life and independence. The LVN must have a specific set of skills in order to adequately and effectively assess the resident, including: a physical assessment; a functional assessment; and any additional information about the resident that would be used to develop the care plan. This module will provide you with all of the information necessary to ensure adequate assessments are completed for each resident in the facility, meeting the state and federal requirements for resident assessment. Overview: Conditions such as functional impairment and dementia are common in nursing home residents. -

HEENT EXAMINIATION ______HEENT Exam Exam Overview

HEENT EXAMINIATION ____________________________________________________________ HEENT Exam Exam Overview I. Head A. Visual inspection B. Palpation of scalp II. Eyes A. Visual Acuity B. Visual Fields C. Extraocular Movements/Near Response D. Inspection of sclera & conjunctiva E. Pupils F. Ophthalmoscopy III. Ears A. External Inspection B. Otoscopy C. Hearing Acuity D. Weber/Rinne IV. Nose A. External Inspection B. Speculum/otoscope C. Sinus areas V. Throat/Mouth A. Mouth Examination B. Pharynx Examination C. Bimanual Palpation VI. Neck A. Lymph nodes B. Thyroid gland 29 HEENT EXAMINIATION ____________________________________________________________ HEENT Terms Acuity – (ehk-yu-eh-tee) sharpness, clearness, and distinctness of perception or vision. Accommodation - adjustment, especially of the eye for seeing objects at various distances. Miosis – (mi-o-siss) constriction of the pupil of the eye, resulting from a normal response to an increase in light or caused by certain drugs or pathological conditions. Conjunctiva – (kon-junk-ti-veh) the mucous membrane lining the inner surfaces of the eyelids and anterior part of the sclera. Sclera – (sklehr-eh) the tough fibrous tunic forming the outer envelope of the eye and covering all of the eyeball except the cornea. Cornea – (kor-nee-eh) clear, bowl-shaped structure at the front of the eye. It is located in front of the colored part of the eye (iris). The cornea lets light into the eye and partially focuses it. Glaucoma – (glaw-ko-ma) any of a group of eye diseases characterized by abnormally high intraocular fluid pressure, damaged optic disk, hardening of the eyeball, and partial to complete loss of vision. Conductive hearing loss - a hearing impairment of the outer or middle ear, which is due to abnormalities or damage within the conductive pathways leading to the inner ear. -

Nursing Students' Perspectives on Telenursing in Patient Care After

Clinical Simulation in Nursing (2015) 11, 244-250 www.elsevier.com/locate/ecsn Featured Article Nursing Students’ Perspectives on Telenursing in Patient Care After Simulation Inger Ase Reierson, RN, MNSca,*, Hilde Solli, RN, MNSc, CCNa, Ida Torunn Bjørk, RN, MNSc, Dr.polit.a,b aFaculty of Health and Social Studies, Institute of Health Studies, Telemark University College, 3901 Porsgrunn, Norway bFaculty of Medicine, Institute of Health and Society, Department of Nursing Science, University of Oslo, 0318 Oslo, Norway KEYWORDS Abstract telenursing; Background: This article presents the perspectives of undergraduate nursing students on telenursing simulation; in patient care after simulating three telenursing scenarios using real-time video and audio nursing education; technology. information and Methods: An exploratory design using focus group interviews was performed; data were analyzed us- communication ing qualitative content analysis. technology; Results: Five main categories arose: learning a different nursing role, influence on nursing assessment qualitative content and decision making, reflections on the quality of remote comforting and care, empowering the pa- analysis tient, and ethical and economic reflections. Conclusions: Delivering telenursing care was regarded as important yet complex activity. Telenursing simulation should be integrated into undergraduate nursing education. Cite this article: Reierson, I. A., Solli, H., & Bjørk, I. T. (2015, April). Nursing students’ perspectives on telenursing in patient care after simulation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11(4), 244-250. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ecns.2015.02.003. Ó 2015 International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning. Published by Elsevier Inc. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

Advanced Interpretation of Adult Vital Signs in Trauma William D

Advanced Interpretation of Adult Vital Signs in Trauma William D. Hampton, DO Emergency Physician 26 March 2015 Learning Objectives 1. Better understand vital signs for what they can tell you (and what they can’t) in the assessment of a trauma patient. 2. Appreciate best practices in obtaining accurate vital signs in trauma patients. 3. Learn what teaching about vital signs is evidence-based and what is not. 4. Explain the importance of vital signs to more accurately triage, diagnose, and confidently disposition our trauma patients. 5. Apply the monitoring (and manipulation of) vital signs to better resuscitate trauma patients. Disclosure Statement • Faculty/Presenters/Authors/Content Reviewers/Planners disclose no conflict of interest relative to this educational activity. Successful Completion • To successfully complete this course, participants must attend the entire event and complete/submit the evaluation at the end of the session. • Society of Trauma Nurses is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation. Vital Signs Vital Signs Philosophy: “View vital signs as compensatory to the illness/complaint as opposed to primary.” Crowe, Donald MD. “Vital Sign Rant.” EMRAP: Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives. February, 2010. Vital Signs Truth over Accuracy: • Document the true status of the patient: sick or not? • Complete vital signs on every patient, every time, regardless of the chief complaint. • If vital signs seem misleading or inaccurate, repeat them! • Beware sending a patient home with abnormal vitals (especially tachycardia)! •Treat vital signs the same as any other diagnostics— review them carefully prior to disposition. The Mother’s Vital Sign: Temperature Case #1 - 76-y/o homeless ♂ CC: 76-y/o homeless ♂ brought to the ED by police for eval. -

Cardiovascular Assessment

Cardiovascular Assessment A Home study Course Offered by Nurses Research Publications P.O. Box 480 Hayward CA 94543-0480 Office: 510-888-9070 Fax: 510-537-3434 No unauthorized duplication photocopying of this course is permitted Editor: Nurses Research 1 HOW TO USE THIS COURSE Thank you for choosing Nurses Research Publication home study for your continuing education. This course may be completed as rapidly as you desire. However there is a one-year maximum time limit. If you have downloaded this course from our website you will need to log back on to pay and complete your test. After you submit your test for grading you will be asked to complete a course evaluation and then your certificate of completion will appear on your screen for you to print and keep for your records. Satisfactory completion of the examination requires a passing score of at least 70%. No part of this course may be copied or circulated under copyright law. Instructions: 1. Read the course objectives. 2. Read and study the course. 3. Log back onto our website to pay and take the test. If you have already paid for the course you will be asked to login using the username and password you selected when you registered for the course. 4. When you are satisfied that the answers are correct click grade test. 5. Complete the evaluation. 6. Print your certificate of completion. If you have a procedural question or “nursing” question regarding the materials, call (510) 888-9070 for assistance. Only instructors or our director may answer a nursing question about the test. -

Blood Pressure Year 1 Year 2 Core Clinical/Year 3+

Blood Pressure Year 1 Year 2 Core Clinical/Year 3+ Do Do • Patient at rest for 5 minutes • Measure postural BP and pulse in patients with a • Arm at heart level history suggestive of volume depletion or • Correct size cuff- bladder encircles 80% of arm syncope • Center of cuff aligns with brachial artery -Measure BP and pulse in supine position • Cuff wrapped snugly on bare arm with lower -Slowly have patient rise and stand (lie them down edge 2-3 cm above antecubital fossa promptly if symptoms of lightheadedness occur) • Palpate radial artery, inflate cuff to 70 mmHg, -Measure BP and pulse after 1 minute of standing then increase in 10 mmHg increments to 30 mmHg above point where radial pulse disappears. Know Deflate slowly until pulse returns; this is the • Normally when a person stands fluid shifts to approximate systolic pressure. lower extremities causing a compensatory rise in • Auscultate the Korotkoff sounds pulse by up to 10 bpm with BP dropping slightly -place bell lightly in antecubital fossa • Positive postural vital signs are defined as -inflate BP to 20-30mmHg above SBP as determined symptoms of lightheadedness and/or a drop in by palpation SBP of 20 mmHg with standing -deflate cuff at rate 2mmHg/second while auscultating • Know variations in BP cuff sizes -first faint tapping (Phase I Korotkoff) = SBP; • A lack of rise in pulse in a patient with an Disappearance of sound (Phase V Korotkoff)=DBP orthostatic drop in pressure is a clue that the Know cause is neurologic or related or related to -Korotkoff sounds are lower pitch, better heard by bell medications (eg. -

Use of Nursing Diagnosis in CA Nursing Schools

USE OF NURSING DIAGNOSIS IN CALIFORNIA NURSING SCHOOLS AND HOSPITALS January 2018 Funded by generous support from the California Hospital Association (CHA) Copyright 2018 by HealthImpact. All rights reserved. HealthImpact 663 – 13th Street, Suite 300 Oakland, CA 94612 www.healthimpact.org USE OF NURSING DIAGNOSIS IN CALIFORNIA NURSING SCHOOLS AND HOSPITALS INTRODUCTION As part of the effort to define the value of nursing, a common language continues to arise as a central issue in understanding, communicating, and carrying out nursing's unique role in identifying and treating patient response to illness. The diagnostic process and evidence-based interventions developed and subsequently implemented by a practice discipline describe its unique contribution, scope of accountability, and value. The specific responsibility registered nurses (RN) have in assessing patient response to health and illness and determining evidence-based etiology is within the realm of nursing’s autonomous scope of practice, and is referred to as nursing diagnosis. It is an essential element of the nursing process and is followed by implementing specific interventions within nursing’s scope of practice, providing evidence that links professional practice to health outcomes. Conducting a comprehensive nursing assessment leading to the accurate identification of nursing diagnoses guides the development of the plan of care and specific interventions to be carried out. Assessing the patient’s response to health and illness encompasses a wide range of potential problems and actual concerns to be addressed, many of which may not arise from the medical diagnosis and provider orders alone, yet can impede recovery and impact health outcomes. Further, it is critically important to communicate those problems, potential vulnerabilities and related plans of care through broadly understood language unique to nursing. -

Patient Assessment: 3 Techniques of Physical Examination: 2

Patient Assessment: 3 Techniques of Physical Examination: 2 W4444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 UNIT TERMINAL OBJECTIVE 3-2 At the completion of this unit, the EMT-Critical Care Technician student will be able to explain the significance of physical exam findings commonly found in emergency situations. COGNITIVE OBJECTIVES At the completion of this unit, the EMT-Critical Care Technician student will be able to: 3-2.1 Define the terms inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation. (C-1) 3-2.2 Describe the techniques of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. (C-1) 3-2-3 Review the procedure for taking and significance of vital signs (pulse, respiration, and blood pressure.) (C-2) 3-2.4 Describe the evaluation of mental status. (C-1) 3-2.5 Evaluate the importance of a general survey. (C-3) 3-2.6 Describe the examination of skin and nails. (C-1) 3-2.7 Differentiate normal and abnormal findings of the assessment of the skin. (C-3) 3-2.8 Distinguish the importance of abnormal findings of the assessment of the skin. (C-3) 3-2.9 Describe the normal and abnormal assessment findings of the head (including the scalp, skull, face and skin). (C-1) 3-2.10 Describe the examination of the head (including the scalp, skull, face, and skin). (C-1) 3-2.11 Describe the examination of the eyes. (C-1) 3-2.12 Distinguish between normal and abnormal assessment findings of the eyes. (C-3) 3-2.13 Describe the examination of the ears. (C-1) 3-2.14 Differentiate normal and abnormal assessment findings of the ears. -

An Examination of Vascular Responses to Acute Isometric Handgrip Exercise and a Complementary Ischemic-Reperfusion Cuff Protocol

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Winter 2014 An examination of vascular responses to acute isometric handgrip exercise and a complementary ischemic-reperfusion cuff protocol Joshua Seifarth University of Windsor, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Seifarth, Joshua, "An examination of vascular responses to acute isometric handgrip exercise and a complementary ischemic- reperfusion cuff protocol" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 5031. This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. An examination of vascular responses to acute isometric handgrip exercise and a complementary ischemic-reperfusion cuff protocol By: Joshua Seifarth A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Faculty of Human Kinetics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Human Kinetics at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2013 © 2013 Joshua Seifarth An examination of vascular responses to acute isometric handgrip exercise and a complementary ischemic-reperfusion cuff protocol By: Joshua Seifarth APPROVED BY: _____________________________ Dr. -

Patients‟ Vital Signs and the Length of Time Between The

PATIENTS‟ VITAL SIGNS AND THE LENGTH OF TIME BETWEEN THE MONITORING OF VITAL SIGNS DURING TIMES OF EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CROWDING By KIMBERLY D. JOHNSON Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr Chris Winkelman Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of ______Kimberly D. Johnson _______________________________ candidate for the ______PhD_________________________degree *. (signed)_____Chris Winkelman_____________________________ (chair of the committee) ________Mary A. Dolansky___________________________ ________Vicken Y. Totten MD________________________ ________Christopher J. Burant________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) ______December 17, 2010_________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. DEDICATION I dedicate my dissertation to my wonderful family without whom I could not have completed this project. To Erik, my supportive and understanding husband, thank you for not letting me quit and for your endless encouragement and patience. Richard Samuel, you‟re the best project I ever completed. When I started this program I never dreamt that I would finish it with a degree and a child. God is good. My parents, Donald and Shirley Blasko, I thank you for inspiring me -

Module 10: Vital Signs

Module 10: Vital Signs Module 10: Vital Signs Minimum Number of Theory Hours: 3 Recommended Clinical Hours: 6 Statement of Purpose: The purpose of this unit is to prepare students to know how, when and why vital signs are taken and how to report and chart these procedures. Students will learn the correct procedure for measuring temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure. They will learn to recognize and report normal and abnormal findings. Terminology: Temperature: Blood Pressure Pulse Respiration Pain (effects on Vital signs) 1. Afebrile 10. Aneroid manometer 22. Apical 33. Abdominal respirations 46. Acute pain 2. Axilla 11. Bell 23. Arrhythmia 34. Apnea 47. Chronic pain 3. Celsius 12. Diaphragm 24. Bounding 35. Bradypnea 4. Fahrenheit 48. Phantom pain 13. Diastolic 25. Brachial 36. Cheyne-Stokes 5. Febrile 49. Pain scales 6. Metabolism 14. Hypertension 26. Bradycardia 37. Cyanosis 7. Mucosa 15. Hypotension 27. Carotid 38. Diaphragm 8. Pyrexia 16. Orthostatic hypotension 28. Pulse deficit 39. Dyspnea 9. Tympanic 17. Pre-hypertension 29. Radial 40. Labored respiration 18. Pulse pressure 30. Rhythm 41. Orthopnea 19. Sphygmomanometer 31. Thready 42. Shallow respiration 20. Stethoscope 32. Tachycardia 43. Stertorous 21. Systolic 44. Tachypnea 45. Temperature, Pulse, Respiration (TPR) Patient, patient/resident, and client are synonymous terms Californiareferring to Community the person Colleges Chancellor’s Office Nurse Assistant Model Curriculum - Revised December 2018 Page 1 of 46 receiving care Module 10: Vital Signs Patient, resident, and client are synonymous terms referring to the person receiving care Performance Standards (Objectives): Upon completion of three (3) hours of class plus homework assignments and six (6) hours of clinical experience, the student will be able to: 1. -

Mod. 3 Vital Signs

Mod. 3 Vital Signs 1. What is most important to assess during secondary assessment? a. Airway b. Pulse c. Respiration d. Chief complaint 2. The first set of vital sign measurements obtained are often referred to as which of the following? a. Baseline vital signs b. Normal vital signs c. Standard vital signs d. None of the above 3. A patient with a pulse rate of 120 beats per minute is considered which of the following? a. Dyscardic b. Normocardic c. Tachycardic d. Bradycardic 4. Where do baseline vital signs fit into the sequence of patient assessment? a. Ongoing assessment b. At primary assessment c. At secondary assessment d. At the patient's side 5. In a conscious adult patient, which of the following pulses should be assessed initially? a. Brachial b. Radial c. Carotid d. Pedal 6. You are assessing a 55-year-old male complaining of chest pain and have determined that his radial pulse is barely palpable. You also determine that there were 20 pulsations over a span of 30 seconds. Based on this, how would you report this patient's pulse? a. Pulse 20, weak, and regular b. Pulse 20 and weak c. Pulse 40 and weak d. Pulse 40, weak, and irregular 7. Which of the following are the vital signs that need to be recorded? a. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature and condition b. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature and condition, pupils, blood pressure, and bowel sounds c. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature and condition, pupils, and blood pressure d. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature, pupils, and blood pressure 8.