Christine Liao Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September/October 2016 Volume 15, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 INSI DE Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Interview with Raqs Media Collective on the 2016 Shanghai Biennale Artist Features: Cui Xiuwen, Qu Fengguo, Ying Yefu, Zhou Yilun Buried Alive: Chapter 1 US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 C ONT ENT S 23 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Sophia Kidd 23 Qu Fengguo: Temporal Configurations Julie Chun 36 36 Cui Xiuwen Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky 48 Propositioning the World: Raqs Media Collective and the Shanghai Biennale Maya Kóvskaya 59 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Danielle Shang 48 67 Art Labor and Ying Yefu: Between the Amateur and the Professional Jacob August Dreyer 72 Buried Alive: Chapter 1 (to be continued) Lu Huanzhi 91 Chinese Name Index 59 Cover: Zhang Yu, One Man's Walden Pond with Tire, 2014, 67 performance, one day, Lijiang. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Chen Ping, David Chau, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist, and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Performance art has a strong legacy in FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum southwest China, particularly in the city EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian of Chengdu. Sophia Kidd, who previously EDITORS Julie Grundvig contributed two texts on performance art in this Kate Steinmann Chunyee Li region (Yishu 44, Yishu 55), updates us on an EDITORS (CHINESE VERSION) Yu Hsiao Hwei Chen Ping art medium that has shifted emphasis over the Guo Yanlong years but continues to maintain its presence CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde WEB SITE EDITOR Chunyee Li and has been welcomed by a new generation ADVERTISING Sen Wong of artists. -

MAY 19Th 2018

5z May 19th We love you, Archivist! MAY 19th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

The GPPA Report

THE GPPA Report SPRING 2018 THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE GREATER PITTSBURGH PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION A Letter from the President VICTOR BARBETTI, PHD, LICENSED PSYCHOLOGIST Dear GPPA Members, They will be joining existing Board members Drs. Teal Fitzpatrick (re- HOPE YOU ARE well and that you’re enjoying these warmer, elected), Nick Flowers, George sunnier days of late spring. Since I moved from the South to I Herrity, and William Hasek. Please Pittsburgh some 20 plus years ago, I have always enjoyed the join me in welcoming our newest distinct changes we experience here from season to season. The Board members. transitions are quite noticeable and bring with them anticipation As my time as Board President and excitement for the new. Change is good, I believe. It keeps winds down, I find myself reflect- us on our toes, and prevents us from settling too deep into our ing fondly over the past five years routines. and the work we’ve accomplished I’m excited to announce to the Membership that GPPA has re- together. Whether it’s honoring cently been granted Continuing Education status from the Ameri- a colleague through the Legacy can Psychological Association. During the last cycle (Fall 2016 Award program, or making new connections at a Networking - Spring 2017) the Board evaluated the feasibility of re-applying Fair, GPPA continues to facilitate opportunities for both new for CE granting privileges and, under the leadership of Dr. Teal and seasoned psychologists in the region. None of this would be Fitzpatrick, the CE Application committee has been very busy possible without the hard work of its members and the count- over the past year working to re-submit our application to APA. -

COMPARATIVE VIDEOGAME CRITICISM by Trung Nguyen

COMPARATIVE VIDEOGAME CRITICISM by Trung Nguyen Citation Bogost, Ian. Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2006. Keywords: Mythical and scientific modes of thought (bricoleur vs. engineer), bricolage, cyber texts, ergodic literature, Unit operations. Games: Zork I. Argument & Perspective Ian Bogost’s “unit operations” that he mentions in the title is a method of analyzing and explaining not only video games, but work of any medium where works should be seen “as a configurative system, an arrangement of discrete, interlocking units of expressive meaning.” (Bogost x) Similarly, in this chapter, he more specifically argues that as opposed to seeing video games as hard pieces of technology to be poked and prodded within criticism, they should be seen in a more abstract manner. He states that “instead of focusing on how games work, I suggest that we turn to what they do— how they inform, change, or otherwise participate in human activity…” (Bogost 53) This comparative video game criticism is not about invalidating more concrete observances of video games, such as how they work, but weaving them into a more intuitive discussion that explores the true nature of video games. II. Ideas Unit Operations: Like I mentioned in the first section, this is a different way of approaching mediums such as poetry, literature, or videogames where works are a system of many parts rather than an overarching, singular, structured piece. Engineer vs. Bricoleur metaphor: Bogost uses this metaphor to compare the fundamentalist view of video game critique to his proposed view, saying that the “bricoleur is a skillful handy-man, a jack-of-all-trades who uses convenient implements and ad hoc strategies to achieve his ends.” Whereas the engineer is a “scientific thinker who strives to construct holistic, totalizing systems from the top down…” (Bogost 49) One being more abstract and the other set and defined. -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

Program Book

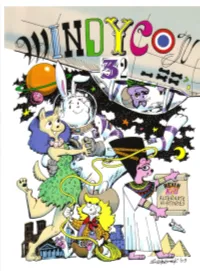

W Congratu lations to m Harry Turtledove WindyCon Guest of Honor HARRY I I if 11T1! \ / Fr6m the i/S/3 RW. ; Ny frJ' 11 UU bestselling author of TURTLEDOVE I Xi RR I THE SONS Of THE SOUTH Turtledove curious A of > | p^ ^p« | M| B | JR : : Rallied All I I II I Al |m ' Curious Notions In High Places 0-765-34610-9 • S6.95ZS9.99 Can. 0-765-30696-4 • S22.95/S30.95 Can. In paperback December 2005 In hardcover January 2006 In a parallel-world twenty-first century Harry Turtledove brings us to the twenty- San Francisco, Paul Goines and his father first century Kingdom ofVersailles, where must obtain raw materials for our timeline slavery is still common. Annette Klein while guarding the secret of Crosstime belongs to a family of Crosstime Traffic Traffic. When they fall under suspicion, agents, and she frequently travels between Paul and his father must make up a lie that two worlds. When Annette’s train is attacked puts Crosstime Traffic at risk. and she is separated from her parents, she wakes to find herself held captive in a caravan “Entertaining,. .Turtledove sets up of slaves and Crosstime Traffic may never a believable alternate reality with recover her. impeccable research, compelling characters and plausible details.” “One of alternate history’s authentic —Romantic Times BookClub Magazine, modern masters.” —Booklist three-star review rwr www.roi.com Adventures in Alternate History 'w&ritlh. our Esteemed Guests of Honor Harry Turtledove Bill Holbrook Gil G^x»sup<1 Erin Gray Jim Rittenhouse Mate s&nd Eouie jBuclklin Mark Osier Esther JFriesner grrad si xM.'OLl'ti't'o.de of additional guests ijrud'o.dlxxg Alex and JPliyllis Eisenstein Eric IF lint Poland Green axidL Erieda Murray- Jody Lynn J^ye and IBill Fawcett Frederik E»olil and ESlizzsJbetlx Anne Hull Tom Smith Gene Wolfe November 11» 13, 2005 Ono Weekend Only! Capricon 26 -Putting the UNIVERSE into UNIVERSITY Now accepting applications for Spring 2006 (Feb. -

Curriculum Vitae: Stephen Reysen Contact: Stephen Reysen Email: [email protected] Webpage

Curriculum Vitae: Stephen Reysen Contact: Stephen Reysen Email: [email protected] Webpage: https://sites.google.com/site/stephenreysen/ Texas A&M University-Commerce Department of Psychology and Special Education Commerce, TX 75429 Phone: (903) 886-5940 Fax: (903) 886-5510 Employment: 2015-Present Associate Professor, Texas A&M University-Commerce (TAMUC) 2009-2015 Assistant Professor, Texas A&M University-Commerce (TAMUC) Education: 2005-2009 University of Kansas (KU) Ph.D. Social Psychology, minor in Statistics 2003-2005 California State University, Fresno (CSUF) M.A. General Psychology, Emphasis: Social 1999-2003 University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) B.A. Intensive Psychology Editor: 2010-Present Journal of Articles in Support of the Null Hypothesis Co-Chair Social Sciences Area Committee: 2017-Present Fandom and Neomedia Studies Association, Social Sciences Studies Area Books: Edwards, P., Chadborn, D. P., Plante, C., Reysen, S., & Redden, M. H. (2019). Meet the bronies: The psychology of adult My Little Pony fandom. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. Reysen, S., & Katzarska-Miller, I. (2018). The psychology of global citizenship: A review of theory and research. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Nominated for International Society of Political Psychology Alexander George Book Award] [Nominated for Society for General Psychology William James Book Award] Plante, C. N., Reysen, S., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. C. (2016). FurScience! A summary of five years of research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Waterloo, Ontario: FurScience. Articles: Katzarska-Miller, I., & Reysen, S. (2019). Educating for global citizenship: Lessons from psychology. Childhood Education, 95(6), 24-33. Reysen, S., Plante, C. N., Roberts, S. E., & Gerbasi, K. -

Old Furnace Artist Residency: Art Is a Conjunction Jon William Henry James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2016 Old Furnace artist residency: Art is a conjunction Jon William Henry James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Sculpture Commons Recommended Citation Henry, Jon William, "Old Furnace artist residency: Art is a conjunction" (2016). Masters Theses. 105. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/105 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Old Furnace Artist Residency Jon Henry A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts School of Art, Design & Art History April 2016 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair : Greg Stewart Committee Members/ Readers: Stephanie Williams Rob Mertens Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... ii Intro ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Conceptual Background ...................................................................................................... 8 Pushback .......................................................................................................................... -

The Right to Play

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 49 Issue 1 State of Play Article 9 January 2004 The Right to Play Edward Castronova Indiana University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Computer Law Commons, Gaming Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Edward Castronova, The Right to Play, 49 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2004-2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\49-1\NLR101.txt unknown Seq: 1 8-DEC-04 12:21 THE RIGHT TO PLAY EDWARD CASTRONOVA* I. INTRODUCTION The virtual worlds now emerging on the Internet manifest themselves with two faces: one invoking fantasy and play, the other merely extending day-to-day existence into a more entertaining cir- cumstance. In this Paper, I argue that the latter aspect of virtual worlds has begun to dominate the former, and will continue to do so, blurring and eventually erasing the “magic circle” that, to now, has allowed these places to render unique and valuable services to their users. Virtual worlds represent a new technology that allows deeper and richer access to the mental states invoked by play, fan- tasy, myth, and saga. These mental states have immense intrinsic value to the human person, and therefore any threats to the magic circle are also threats to a person’s well-being. -

We All Need to Play

Issue 49 changeagent.nelrc.org September 2019 THE CHANGE Adult Education for Social Justice: News, AGENT Issues, and Ideas We All Need to Play Everyone Needs to Play: 3 Walking is My Play: 4 Red Tricycle: 5 A Game for Learning: 6 Just This One Time: 8 Fair Play for a Fair Future: 10 The Way I Got My Dolls: 12 Fun in a Farming Village: 14 Hide-and-Seek in War: 15 Everybody Played: 16 Passing the Ball On: 18 I Still Like to Hula Hoop: 19 We Were Captains of Our Ships: 20 The Caves: 21 Not Much Time to Play: 22 Sacred Play: 24 Old Games vs. New Games: 26 Strict Mom: 27 Nothing to Compare: 28 Siri, Why Is Mom So Boring: 29 Addiction to Video Games: 30 Hooked on Video Games: 32 Play for Bodies, Minds, and Souls: 34 Who Is Allowed to Play? 36 Playtime: Not Just Fun and Games: 38 Football Taught Me to Embrace Challenges: 40 Play Sports and Learn: 41 My Tamagotchi Taught Me: 42 Imagination is the Best Play: 43 Concepción Saravia (above as a child with her baseball More than Marbles: 44 bat, and left as an adult) begged her mother to let her Be Happy—Play: 47 play baseball. Read her story on p. 8. Whole Body Development through Play: 48 ENGAGING, EMPOWERING, AND READY-TO-USE. Early Childhood Educator Career Student-generated, relevant content in print & audio at various levels of Pathway: 49 complexity—designed to teach basic skills & transform & inspire adult learners. I Wanted to Play: 50 Gamification: 52 A MAGAZINE & WEBSITE: CHANGEAGENT.NELRC.ORG The Change Agent is the bi- A Note from the Editor: annual publication of The New Our writers in this issue are from all over the world, from Mexico to Mol- England Literacy Resource Center. -

The Search for the Holy Curl... Grail Our Con Chair Welcomes You to Denfur 2021!

DenFur 2021 The Search for the Holy Curl... Grail Our Con Chair Welcomes You to DenFur 2021! I wanted to introduce myself to you all now that I am the new con chair for DenFur 2021! My name is Boiler (or Boilerroo), but you can call me Mike if you want to! I've been in the furry fandom since 1997 (24 years in total!) – time flies when you're having fun! I am a non-binary transmasc person and I use he/hIm pronouns. If you don't know what that means, you are free to ask me and I will explain – but in sum: I am trans! I am also an artist, part time media arts instructor and a full-time librarian in my outside-of-furry life. I am very excited to usher in the next years of DenFur – I know the pandemic has really been an unprecedented time in our lives and affected us all deeply, but I am hoping with the start of DenFur we can reunite as a community once more, safely and with a whole lot of furry fun! Of course, we will have a lot of rules, safeguards and requirements in place to make sure that our event is held as safely as possible. Thank you everyone for your patience as we have worked diligently to host this event! I hope you all have an amazing convention, and be sure to say hello! TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 Page 9 Con Chair Welcome Staff Page 4 Page 10 Theme Dealers Den List Table of contents and artist credit for pages Page 5 Page 11-13 Convention Operating Hours Schedule Grid Page 6 Page 14-21 Convention Map Panel Information and Events Page 7 Page 22 Guests of Honor Altitude Safety Page 8 Page 23-24 Charity Convention Code of Conduct ARTIST CREDIT Page 1 Page 11 Foxene Foxene Page 2 Page 20 RedCoatCat Ruef n’ Beeb Page 4 Page 22 Boiler Ruef n’ Beeb Page 5 Page 23 Basil Boiler Page 6 Page 26 Basil Ritz Page 9 Basil On Our Journey In AD 136:001:20:50,135 years after the first contact between the Protogen and the furry survivors, the ACC-1001 Denfur launched a crew of 2500 furries into space. -

Alt.Fan.Furry

Subject: [alt.fan.furry] A Furry Comic Book List Posted by infopage on Fri, 30 Nov 2012 10:57:24 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message Archive-name: furry/comics-list Posting-Frequency: Posted on the 13th and 30th of each month, and Feb. 28 URL: http://captainpackrat.com/furry/list.htm Last-Modified: December 24, 2005 A Not Quite Complete, but None the Less, Very Thorough Furry Comic Book List (Updated December 24, 2005) (Please note that there are no children's comic books listed here.) All comics are B&W unless otherwise noted. Many of these books can be obtained from the Individual Publishers. A * indicates that the publisher is listed on the Furry Publisher's List, posted separately. A $ indicates that I own a copy of that book, and can provide much more information. Please write me for more detailed information. Definition of comic book/fanzine sizes: Mini-comic: 4.25" x 5.5" Digest: 5.5" x 8.5" Super Digest: 7" x 8.5" A4 Digest: 5.845" x 8.27" Standard: 6-5/8" x 10-1/4" <64 pages Trade-paperback: 6-5/8" x 10-1/4", >64 pages Magazine: 8-1/2" x 11" A4 Magazine: 8.27" x 11.69" I would like to thank everyone who has helped by sending information. If you have any additions, corrections, suggestions, or comments, please E-Mail me. -- 0-9 -- "1001 Arabian Tails" Drawn and Written by Juan Alfonso, Published by Conquest Press. Adults Only. One-shot. A new twist on the tale of Aladdin.