Study on “EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Different Perspective for Coaching and Training Education According to Score Changes During Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships

International Education Studies; Vol. 14, No. 5; 2021 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Different Perspective for Coaching and Training Education According to Score Changes During Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships Berfin Serdil ÖRS1 1 Department of Coaching Education, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Aydin Adnan Menderes University, Aydin, Turkey Correspondence: Berfin Serdil ÖRS, Department of Coaching Education, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Aydin Adnan Menderes University, 09100, Aydin, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 30, 2020 Accepted: February 26, 2021 Online Published: April 25, 2021 doi:10.5539/ies.v14n5p63 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n5p63 Abstract Rhythmic gymnasts repeat elements thousands of times which may put a risk on gymnasts’ health. It is necessary to protect the current and future health conditions of young gymnasts, especially in the growth process. There is a lack of knowledge about training education on rhythmic gymnastics. To suggest innovative changes, the current study aimed to analyze the scores (D, E, and total scores) of the first 24 gymnasts competing in 34th and 36th Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships (ECh). Research data were collected from 24 rhythmic gymnasts’ scores, from the 34th ECh and 36th ECh. Difficulty (D), Execution (E), and total scores for hoop, ball, clubs, ribbon were analyzed. Conformity of data to normal distribution was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables with normal distribution were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)/independent samples t-test and for variables not fitting normal distribution, Mann Whitney U/Kruskal Wallis H test was used. -

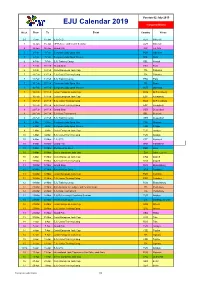

EJU Calendar 2019 Changes/Additions

Version 02 July 2019 EJU Calendar 2019 changes/additions Week From To Event Country Venue 2-3 7-Jan 15-Jan EJU OTC AUT Mittersill 3 14-Jan 15-Jan IJF Referee and Coach Seminar AUT Mittersill 4 24-Jan 26-Jan Grand Prix ISR Tel Aviv 5 2-Feb 3-Feb European Judo Open Men POR Odivelas 5 2-Feb 3-Feb European Judo Open Women BUL Sofia 6 4-Feb 7-Feb EJU Training Camp BEL Herstal 6 9-Feb 10-Feb Grand Slam FRA Paris 6 9-Feb 10-Feb Cadet European Judo Cup ITA Follonica 7 11-Feb 13-Feb EJU Cadet Training Camp ITA Follonica 7 11-Feb 14-Feb EJU Training Camp FRA Paris 7 16-Feb 17-Feb European Judo Open Men ITA Rome 7 16-Feb 16-Feb European Judo Open Women AUT Oberwart 7 16-Feb 17-Feb Junior European Judo Cup RUS St Petersburg 7 16-Feb 17-Feb Cadet European Judo Cup ESP Fuengirola 8 18-Feb 20-Feb EJU Junior Training Camp RUS St Petersburg 8 18-Feb 20-Feb EJU Cadet Training Camp ESP Fuengirola 8 22-Feb 24-Feb Grand Slam GER Dusseldorf 8 24-Feb 24-Feb EJU Kata Tournament BEL Brussels 9 25-Feb 28-Feb EJU Training Camp GER Dusseldorf 9 2-Mar 3-Mar European Judo Open Men POL Warsaw 9 2-Mar 2-Mar European Judo Open Women CZE Prague 9 2-Mar 3-Mar Cadet European Judo Cup TUR Antalya 10 4-Mar 6-Mar EJU Cadet Training Camp TUR Antalya 10 4-Mar 10-Mar EJU OTC CZE Nymburk 10 8-Mar 10-Mar Grand Prix MAR Marrakesh 10 9-Mar 10-Mar Panamerican Open PER Lima 10 9-Mar 10-Mar Senior European Judo Cup SUI Uster - Zürich 10 9-Mar 10-Mar Cadet European Judo Cup CRO Zagreb 11 11-Mar 13-Mar EJU Cadet Training Camp CRO Zagreb 11 15-Mar 17-Mar Grand Slam RUS Ekaterinburg 11 -

Kuwait Says It Respects Iran's Integrity After Ahvaz Meeting

JUMADA ALAWWAL 4, 1441 AH MONDAY, DECEMBER 30, 2019 28 Pages Max 23º Min 08º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18023 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Noticeable change in Jleeb Turkey will not withdraw Trump, Syria and Facebook: Liverpool lean on VAR to edge 5 after municipal crackdown 6 from army posts in Idlib 20 Volatile cocktail of the 2010s 28 Wolves; Chelsea sink Arsenal Kuwait says it respects Iran’s integrity after Ahvaz meeting Deputy FM reassures Iranian envoy, says meeting was held without approval By B Izzak Damkhi files KUWAIT: Kuwait said yesterday that it respects Iran’s “territorial integrity”, a day after Tehran summoned its envoy to protest to grill Aseeri against Kuwaiti officials meeting Iranian sepa- By B Izzak ratists. In a meeting with Iran’s ambassador Mohammad Irani, Kuwait’s deputy foreign KUWAIT: Islamist opposition MP minister Khaled Al-Jarallah stressed that his Adel Al-Damkhi yesterday filed to grill country’s foreign policy was based on respect- Minister of Social Affairs and Labor ing “sovereignty and non-interference in inter- Ghadeer Aseeri barely a week after nal affairs and good neighborliness”, KUNA she took office, over allegations that said. KUNA said Jarallah had reassured Iran’s ambassador that Kuwait respects the “Islamic she challenged the integrity of MPs. In Adel Al-Damkhi his brief grilling, Damkhi charged the Republic of Iran’s territorial integrity”. Iran’s foreign ministry had said on minister of violating the principles of for two more weeks. The minister Saturday that it summoned Kuwait’s envoy to cooperation between the National became a target of criticism by several Tehran to protest against its officials meeting Assembly and the government by issu- opposition MPs for tweets she posted a separatist group and holding an “anti-Iran ing statements deemed offensive to on her account some eight years ago meeting”. -

Selected References

SELECTED REFERENCES Events and Tours • 2016 Summer Olympic Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies – Rio, Brasil • 2014 Winter Olympic Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies - Sochi, Russia • 2012 Summer Olympic Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies - London, United Kingdom • 2012 Paralympics Opening and Closing Ceremonies - Beijing, China • 2010 Winter Olympic Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies - Vancouver, BC, Canada • 2008 Summer Olympic Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies - Beijing, China • 2004 Summer Olympic Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies - Athens, Greece • 2007 Rugby World Cup Opening Ceremony, Stade de France - Paris, France • 2006 Soccer World Cup Opening Ceremony - Munich, Germany st • 1 European Games 2015 - Baku, Azerbaijan th • 15 Pacific Games 2015 - Papua New Guinea th • 20 World Youth Day - Cologne, Germany th • 28 SEA Games, Opening and Closing Ceremonies, Singapore nd • 32 America’s Cup - Valencia, Spain • Abu Dhabi Classics - Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates • ATP Grand Slam US Open Tennis 2013 - New York, USA • ATP Monte-Carlo Tennis Masters - Monaco • Barbra Streisand European Tour • Bastille Day 2015 – Paris, France • Bastille Day Celebration - Le Chateau de Chantilly, France • Billy Joel & Elton John “Face 2 Face” Tour • Björk Tour 2015 • Bob Dylan European Tour • Bon Jovi "The Circle World” Tour • British Summer Time 2014, 2015 - London, UK • Britney Spears “The Circus” Tour • Carnival - Salvador, Brazil • Coldplay “Mylo Xyloto” Tour • Coldplay “Viva la Vida” Tour • Coldpaly “Head Full of Dreams” Tour • -

Legal Effects of Eu Agreements

Oxford Studies in European Law General Editors: Paul Craig and Graı´nne de Burca THE LEGAL EFFECTS OF EU AGREEMENTS This is an open access version of the publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/), which permits non-commercial reproduction and distribution of the work, in any medium, provided the original work is not altered or transformed in any way, and that the work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact [email protected] Oxford Studies in European Law Series Editors: Paul Craig, Professor of English Law at St John’s College, Oxford and Gra´inne de Burca, Professor of Law at New York University School of Law The aim of this series is to publish important and original research on EU law. The focus is on scholarly monographs, with a particular emphasis on those which are interdisciplinary in nature. Edited collections of essays will also be included where they are appropriate. The series is wide in scope and aims to cover studies of particular areas of substantive and of institutional law, historical works, theoretical studies, and analyses of current debates, as well as questions of perennial interest such as the relationship between national and EU law and the novel forms of governance emerging in and beyond Europe. The fact that many of the works are interdisciplinary will make the series of interest to all those concerned with the governance and operation of the EU. European Law and New -

„Applicable Research in Judo”

6TH EUROPEAN JUDO SCIENCE & RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM AND 5TH SCIENTIFIC AND PROFESSIONAL CONFERENCE – „APPLICABLE RESEARCH IN JUDO” PROCEEDINGS BOOK Editors: Hrvoje Sertić, Sanda Čorak and Ivan Segedi Organizers: European Judo Union Croatian Judo Federation University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology, Croatia 12-14. JUNE 2019. POREČ - CROATIA Publisher: University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology, Croatia For the Publisher: Assoc.Prof Tomislav Krističević, Dean of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology, Croatia Editors: Prof. Hrvoje Sertić – University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Sanda Čorak, PhD – Croatian Judo Federation Assist.Prof. Ivan Segedi – University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) International editorial board: Jožef Šimenko, PhD - University of Greenwich (Great Britain) Prof. Michel Calmet – Universite Montpellier - Aix-Marseille Université (France) Prof. Emerson Franchini - University of Sao Paulo (Brasil) Prof. Husnija Kajmović – Univerity of Sarajevo Faculty of Sport and Physical Education (BiH) Assoc.Prof. Tomislav Krističević, University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Assist.Prof. Sanja Šalaj - University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Assoc.Prof. Ljubomir Antekolović - University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Assoc.Prof. Maja Horvatin - University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Prof. Lana Ružić - University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Prof. Branka Matković - University of Zagreb Faculty of Kinesiology (Croatia) Assoc.Prof. Mario -

MAY / JUDO / EUROPE JUDO / / MAY 1St of May 2020 – Master Class for Young Judoka 6-12 Y.O

Prague 2020 - Czech Republic Dear Judo Friends! During the Senior European Judo Championships in Prague, Czech Republic between April 30th and May 3rd 2020, the European Judo Union will organise the traditional Judo Family Fan Camp. This project will once again unite European judo fans, young judoka and families alike for three days in the magnificent Prague O2 Arena. The highlights of the program will be: • the opportunity to meet with great judokas • master classes with judo stars • witnessing the fascinating spectacle on the tatami, the fights between the strongest athletes in Europe. Program: MAY / JUDO / EUROPE JUDO / / MAY 1st of May 2020 – Master Class for young judoka 6-12 y.o. and their coaches 2nd of May 2020 – Master Class for young cadets 15-17 y.o. and their coaches 3rd of May 2020 – «Judo Family Competition» for U8 children and their parents So if you would like to participate in this project, here is how to do it: 1. Registration - to secure your place at champion’s tatami & seat at Special Sector for Judo Family Fan Camp. Accreditation - to receive your card by email and get prepared for the European Championships. 2. Accommodation - free choice - to secure your comfortable stay in Prague during the ECh. So if you decide that you would like to participate in this project, here is how to do it! Step 1 Step 2 Register with EJU form, please send the filled data Pay the Judo Family Fan Camp membership fee to Ms. Maria Konova [email protected] and for accreditation card 40 € /per person (bank card / Pay Pal): Name & Family name EUROPEAN JUDO UNION Nationality REGISTERED ADDRESSES Age 31/6 Triq San Federiku, Valetta, Malta IBAN NR: MT38VALL22013000000040019971724 E-mail BANK OF VALLETTA PLC SWIFT VALLMTMT Your photo for accreditation 3x4 cm Step 3 If you choose the hotel Step 4 Сhoose your accommodation. -

EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward

STUDY Requested by the CULT committee EU sports policy: assessment and possible ways forward Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies EN PE 652.251 - June 2021 3 RESEARCH FOR CULT COMMITTEE EU sports policy: assessment and possible ways forward Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has been entitled to support, coordinate or complement Member States’ activities in sport. European sports policies of the past decade are characterised by numerous activities and by on-going differentiation. Against this backdrop, the study presents policy options in four key areas: the first covers the need for stronger coordination; the second aims at the setting of thematic priorities; the third addresses the reinforcement of the role of the EP in sport and the fourth stipulates enhanced monitoring. This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education. AUTHORS Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln: Jürgen MITTAG / Vincent BOCK / Caroline TISSON Willibald-Gebhardt-Institut e.V.: Roland NAUL / Sebastian BRÜCKNER / Christina UHLENBROCK EUPEA: Richard BAILEY / Claude SCHEUER ENGSO Youth: Iva GLIBO / Bence GARAMVOLGYI / Ivana PRANJIC Research administrator: Katarzyna Anna ISKRA Project, publication and communication assistance: Anna DEMBEK, Kinga OSTAŃSKA Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, European Parliament LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE PUBLISHER To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to updates on our work for -

EUSA Year Magazine 2019-2020

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY SPORTS ASSOCIATION YEAR 2019/20MAGAZINE eusa.eu CONTENTS Page 01. EUSA STRUCTURE 4 02. EUROPEAN UNIVERSITIES CHAMPIONSHIPS 2019 9 03. ENDORSED EVENTS 57 04. CONFERENCES AND MEETINGS 61 05. PROJECTS 75 06. EU INITIATIVES 85 07. UNIVERSITY SPORT IN EUROPE AND BEYOND 107 08. PARTNERS AND NETWORK 125 09. FUTURE PROGRAMME 133 Publisher: European University Sports Association; Realisation: Andrej Pišl, Fabio De Dominicis; Design, Layout, PrePress: Kraft&Werk; Printing: Dravski tisk; This publication is Photo: EUSA, FISU archives free of charge and is supported by ISSN: 1855-4563 2 WELCOME ADDRESS Dear Friends, With great pleasure I welcome you to the pages of Statutes and Electoral Procedure which assures our yearly magazine to share the best memories minimum gender representation and the presence of the past year and present our upcoming of a student as a voting member of the Executive activities. Committee, we became – and I have no fear to say – a sports association which can serve as an Many important events happened in 2019, the example for many. It was not easy to find a proper year of EUSA’s 20th anniversary. Allow me to draw tool to do that, bearing in mind that the cultural your attention to just a few personal highlights backgrounds of our members and national here, while you can find a more detailed overview standards are so different, but we nevertheless on the following pages. achieved this through a unanimous decision- making process. In the build up to the fifth edition of the European Adam Roczek, Universities Games taking place in Belgrade, I am proud to see EUSA and its Institute continue EUSA President Serbia, the efforts made by the Organising their active engagement and involvement in Committee have been incredible. -

EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward

STUDY Requested by the CULT committee EU sports policy: assessment and possible ways forward Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies Directorate-General for Internal Policies EN PE 652.251 - June 2021 3 RESEARCH FOR CULT COMMITTEE EU sports policy: assessment and possible ways forward Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has been entitled to support, coordinate or complement Member States’ activities in sport. European sports policies of the past decade are characterised by numerous activities and by on-going differentiation. Against this backdrop, the study presents policy options in four key areas: the first covers the need for stronger coordination; the second aims at the setting of thematic priorities; the third addresses the reinforcement of the role of the EP in sport and the fourth stipulates enhanced monitoring. This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education. AUTHORS Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln: Jürgen MITTAG / Vincent BOCK / Caroline TISSON Willibald-Gebhardt-Institut e.V.: Roland NAUL / Sebastian BRÜCKNER / Christina UHLENBROCK EUPEA: Richard BAILEY / Claude SCHEUER ENGSO Youth: Iva GLIBO / Bence GARAMVOLGYI / Ivana PRANJIC Research administrator: Katarzyna Anna ISKRA Project, publication and communication assistance: Anna DEMBEK, Kinga OSTAŃSKA Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, European Parliament LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE PUBLISHER To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to updates on our work for -

Otterbein Towers June 1954

PRIKCIPAIS E 0»E HllSDRED SEVENTH COMMENCEMENT Otterbein Towers 6)-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------^ CONTENTS The Cover Page .............................................................. 2 The Editor’s Corner ..................................................... 2 From the Mail Bag ....................................................... 3 Important Meeting of College Trustees ...................... 3 Alumni President’s Greetings ....................................... 4 Alumni Club Meetings................................................... 4 New Alumni Officers ................................................... 4 College Librarian Retires ............................................. 5 Otterbein Confers Five Honorary Degrees.................... 5 Honorary Alumnus Awards ........................................... 6 Dr. Mabel Gardner Honored ....................................... 6 Spessard Dies .................................................................. 6 "Her stately tower Development Fund Report for Five Months....... ........ 7 speaks naught hut power Changes in Alumni Office ............................................. 7 For our dear Otterbein" % A Good Year in Sports ............. S AFROTC Wins High Rating ....................................... 8 Otterbein Towers Class Reunion Pictures ......................................... 9, 10, 11 Editor Before—After............................................................... -

European Commission - White Paper on Sport Luxembourg: Offi Ce for Offi Cial Publications of the European Communities 2007 —208 P

since 1957 NC-30-07-101-EN-C WHITE PAPER ON SPORT ON WHITE PAPER EUROPEAN COMMISSION WHITE PAPER ON SPORT European Commission Directorate-General for education and culture B-1049 Bruxelles / Brussel 32 - (0)2 299 11 11 32 - (0)2 295 57 19 [email protected] EEAC.D3_whitepp_sport_Cover_435x21AC.D3_whitepp_sport_Cover_435x21 1 221/02/20081/02/2008 113:15:343:15:34 European Commission - White paper on sport Luxembourg: Offi ce for Offi cial Publications of the European Communities 2007 —208 p. — 21.0 x 29.7 cm ISBN 978-92-79-06943-7 Europe Direct is a service to help you fi nd answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). SALES AND SUBSCRIPTIONS Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Publications for sale produced by the Offi ce for Offi cial Publications of the European Luxembourg: Offi ce for Offi cial Publications of the European Communities, 2007 Communities are available from our sales agents throughout the world. ISBN 978-92-79-06943-7 You can fi nd the list of sales agents on the Publications Offi ce website (http://publications.europa.eu) or you can apply for it by fax (352) 29 29-42758. © European Communities, 2007 Contact the sales agent of your choice and place your order.