Youth Development: an Ecological Approach to Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Secretariats of Roads Transportation Report 2015

Road Transportation Report: 2015. Category Transfer Fees Amount Owed To lacal Remained No. Local Authority Spent Amount Clearing Amount classification 50% Authorities 50% amount 1 Albireh Don’t Exist Municipality 1,158,009.14 1,158,009.14 0.00 1,158,009.14 2 Alzaytouneh Don’t Exist Municipality 187,634.51 187,634.51 0.00 187,634.51 3 Altaybeh Don’t Exist Municipality 66,840.07 66,840.07 0.00 66,840.07 4 Almazra'a Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 136,262.16 136,262.16 0.00 136,262.16 5 Banizeid Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 154,092.68 154,092.68 0.00 154,092.68 6 Beitunia Don’t Exist Municipality 599,027.36 599,027.36 0.00 599,027.36 7 Birzeit Don’t Exist Municipality 137,285.22 137,285.22 0.00 137,285.22 8 Tormos'aya Don’t Exist Municipality 113,243.26 113,243.26 0.00 113,243.26 9 Der Dibwan Don’t Exist Municipality 159,207.99 159,207.99 0.00 159,207.99 10 Ramallah Don’t Exist Municipality 832,407.37 832,407.37 0.00 832,407.37 11 Silwad Don’t Exist Municipality 197,183.09 197,183.09 0.00 197,183.09 12 Sinjl Don’t Exist Municipality 158,720.82 158,720.82 0.00 158,720.82 13 Abwein Don’t Exist Municipality 94,535.83 94,535.83 0.00 94,535.83 14 Atara Don’t Exist Municipality 68,813.12 68,813.12 0.00 68,813.12 15 Rawabi Don’t Exist Municipality 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 16 Surda - Abu Qash Don’t Exist Municipality 73,806.64 73,806.64 0.00 73,806.64 17 Hay Alkarama Don’t Exist Village Council 7,551.17 7,551.17 0.00 7,551.17 18 Almoghayar Don’t Exist Village Council 71,784.87 71,784.87 0.00 71,784.87 19 Alnabi Saleh Don’t Exist Village Council -

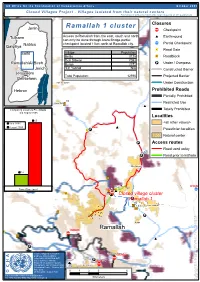

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

Deir Dibwan Town Profile

Deir Dibwan Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory ( 05-11 June 2014) Thursday, 12 June 2014 00:00

Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory ( 05-11 June 2014) Thursday, 12 June 2014 00:00 Tulkarm- Israeli forces destroy a house belonging to a Palestinian family in Far’one village. Reuters Israeli forces continue systematic attacks against Palestinian civilians and property in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) In a new extra-judicial execution, Israeli forces killed a member of an armed group and wounded 3 civilians, including a child, in the Gaza Strip A Palestinian civilian died as he was previously wounded by the Israeli forces in the northwest of Beit Lahia in the northern Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued to use excessive force against peaceful protesters in the West Bank. 3 Palestinian demonstrators were wounded in the demonstrations of Ni’lin and Bil’in, west of Ramallah. 5 Palestinian civilians, including a child, were wounded in a demonstration organized in solidarity with the Palestinian administrative detainees on hunger strike. Israeli forces conducted 76 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank. 28 Palestinian civilians, including 4 children and woman, were arrested. A Palestinian civilian was wounded when Israeli forces moved into al-‘Arroub refugee camp, north of Hebron. Israel has continued its efforts to create a Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem Israeli forces raided the Pal Media office and arrested two of its workers and a guest of “Good Morning Jerusalem” program. Israel continued to impose a total closure on the oPt and has isolated the Gaza Strip from the outside world. Israeli forces established dozens of checkpoints in the West Bank. -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 Dec

Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 Dec. ember 2015) Thursday, 17 December 2015 00:00 Israeli forces continue systematic crimes in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (10 – 16 December 2015) Israeli forces escalated the use of excessive force in the oPt 5 Palestinian civilians were killed and a girl child succumbed to her injuries in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. 96 Palestinian civilians, including 14 children and 5 journalists, were wounded in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued to target the border area along the Gaza Strip. 5 Palestinian civilians were wounded in the southern Gaza Strip in 3 separate attacks. Israeli forces conducted 106 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank 107 Palestinian civilians, including 28 children, were arrested. 20 of them, including 14 children, were arrested in occupied Jerusalem. A number of houses belonging to families of Palestinians, who carried out stabbing and runover attacks, were raided. Moreover, measures of the houses were taken for house demolitions. Israeli gunboats continued to target Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip sea, but no casualties were reported. Jewish majority efforts continued in occupied East Jerusalem. A house in alShaikh Jarrah neighbourhood was demolished and demolition notices were issued. Settlement activities continued in the West Bank. 30 dunums[1] in the northern West Bank were confiscated. Israeli forces turned the West Bank into cantons and continued to impose the illegal closure on the Gaza Strip for the 9th year. Dozens of temporary checkpoints were established in the West Bank and other were reestablished to obstruct the movement of Palestinian civilians. -

The Women's Affairs Technical Committees

The Women’s Affairs Technical Committee Summary Report – 2010 _________________________________________________________ The Women’s Affairs Technical Committees Summary Report for the period of January 1st. 2010 - December 31st. 2010 1 The Women’s Affairs Technical Committee Summary Report – 2010 _________________________________________________________ - Introduction - General Context o General Demographic Situation o Political Situation o Women lives within Patriarchy and Military Occupation - Narrative of WATC work during 2010 in summary - Annexes 1 and 2 2 The Women’s Affairs Technical Committee Summary Report – 2010 _________________________________________________________ Introduction: This is a narrative summary report covering the period of January 2010 until 31 December 2010. The objective of this report is to give a general overview of the work during 2010 in summary and concise activities. At the same time, there have been other reports presented for specific projects and programs. General Context: Following part of the summary report presents the context on which programs, projects and activities were implemented during 2010. Firstly, it gives a general view of some demographic statistics. Secondly, it presents a brief political overview of the situation, and thirdly it briefly presents briefly some of the main actors that affected the life of Palestinian women during 2010. General Demographic situation: Data from the Palestinian Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) shows that the population of the Palestinian Territory is young; the percentage of individuals in the age group (0- 14) was 41.3% of the total population in the Palestinian Territory at end year of 2010, of which 39.4% in the West Bank and 44.4% in Gaza Strip. As for the elderly population aged (65 years and over) was 3.0% of the total population in Palestinian Territory at end year of 2010. -

Traffic, Hazards, and Mobility in the West Bank

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Everyday Occupations: Traffic, Hazards, And Mobility In The esW t Bank Alice Arnold University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, A.(2018). Everyday Occupations: Traffic, Hazards, And Mobility In The West Bank. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4676 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVERYDAY OCCUPATIONS: TRAFFIC, HAZARDS, AND MOBILITY IN THE WEST BANK by Alice Arnold Bachelor of Arts University of Iowa, 2018 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Geography College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Jessica Barnes, Director of Thesis David Kneas, Reader Amy Mills, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Alice Arnold, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii ABSTRACT Mobility in the West Bank is inherently tied to the Israeli military occupation. Each new stage of the decades old conflict comes with new implications for the way Palestinians move around the West Bank. The past years have seen a transition during which the severe mobility restrictions that constituted the closure policy of the second intifada eased and intercity travel has increased. In this study I examine day-to-day experiences of mobility in the West Bank in the post-closure period. -

Syria 2014 Human Rights Report

SYRIA 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The authoritarian regime of President Bashar Asad has ruled the Syrian Arab Republic since 2000. The regime routinely violated the human rights of its citizens as the country witnessed major political conflict. The regime’s widespread use of deadly military force to quell peaceful civil protests calling for reform and democracy precipitated a civil war in 2012, leading to armed groups taking control of major parts of the country. In government-controlled areas, Asad makes key decisions with counsel from a small number of military and security advisors, ministers, and senior members of the ruling Baath (Arab Socialist Renaissance) Party. The constitution mandates the primacy of Baath Party leaders in state institutions and society. Asad and Baath party leaders dominated all three branches of government. In June, for the first time in decades, the Baath Party permitted multi-candidate presidential elections (in contrast to single-candidate referendums administered in previous elections), but the campaign and election were neither free nor fair by international standards. The election resulted in a third seven-year term for Asad. The geographically limited 2012 parliamentary elections, won by the Baath Party, were also neither free nor fair, and several opposition groups boycotted them. The government maintained effective control over its uniformed military, police, and state security forces but did not consistently maintain effective control over paramilitary, nonuniformed proregime militias such as the National Defense Forces, the “Bustan Charitable Association,” or “shabiha,” which often acted autonomously without oversight or direction from the government. The civil war continued during the year. -

Al-Bireh Ramallah Salfit

Biddya Haris Kifl Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Az Zawiya (Salfit) Talfit Salfit As Sawiya Qusra Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Deir Ballut Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Turmus'ayya Al Lubban al Gharbi 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Bani Zeid Deir as Sudan Sinjil Rantis Jilijliya 'Ajjul An Nabi Salih (Bani Zeid al Gharbi) Al Mughayyir (Ramallah) 'Abud Khirbet Abu Falah Umm Safa Deir Nidham Al Mazra'a ash Sharqiya 'Atara Deir Abu Mash'al Jibiya Kafr Malik 'Ein Samiya Shuqba Kobar Burham Silwad Qibya Beitillu Shabtin Yabrud Jammala Ein Siniya Bir Zeit Budrus Deir 'Ammar Silwad Camp Deir Jarir Abu Shukheidim Jifna Dura al Qar' Abu Qash At Tayba (Ramallah) Deir Qaddis Al Mazra'a al Qibliya Al Jalazun Camp 'Ein Yabrud Ni'lin Kharbatha Bani HarithRas Karkar Surda Al Janiya Al Midya Rammun Bil'in Kafr Ni'ma 'Ein Qiniya Beitin Badiw al Mus'arrajat Deir Ibzi' Deir Dibwan 'Ein 'Arik Saffa Ramallah Beit 'Ur at Tahta Khirbet Kafr Sheiyan Al-Bireh Burqa (Ramallah) Beituniya Al Am'ari Camp Beit Sira Kharbatha al Misbah Beit 'Ur al Fauqa Kafr 'Aqab Mikhmas Beit Liqya At Tira Rafat (Jerusalem) Qalandiya Camp Qalandiya Beit Duqqu Al Judeira Jaba' (Jerusalem) Al Jib Jaba' (Tajammu' Badawi) Beit 'Anan Bir Nabala Beit Ijza Ar Ram & Dahiyat al Bareed Deir al Qilt Kharayib Umm al Lahim QatannaAl Qubeiba Biddu An Nabi Samwil Beit Hanina Hizma Beit Hanina al Balad Beit Surik Beit Iksa Shu'fat 'Anata Shu'fat Camp Al Khan al Ahmar (Tajammu' Badawi) Al 'Isawiya. -

Annual Review 2011

Jerusalem-West Bank-Gaza Annual Review 2011 Table of Contents Who We Are 1 Our Work 3 Greetings 5 Sponsor a child today! 6 Ensuring children are cared for, protected & participating! 8 Helping children become educated for life! 14 Ensuring children enjoy good health! 17 Helping children experience the love of God and their 20 neighbours! Public Engagment 22 Finance 24 Who We Are World Vision is dedicated to working with children, families and communities to overcome poverty and injustice. As a Christian relief, development and advocacy organisation, we are dedicated to working with the world’s most vulnerable people. We serve all people regardless of religion, race, ethnicity or gender. Our vision for every child, life in all its fullness; Our prayer for every heart, the will to make it so World Vision wants to see that every child has the opportunity to live a full life. World Vision focuses on improving children’s well-being through child-focused transformational development, disaster management, and promotion of justice. 1 In Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza, World Vision works through a community-based sustainable framework in which children, families, and communities move towards healthy individual development, positive relationships and a context that provides safety, social justice and participation in civil society. World Vision has developed four high-level Child Well-Being Aspirations that define what we mean by ’life in all its fullness’ for children. Our aspirations for girls and boys are that they: ..are cared for, protected and participating ..are educated for life ..enjoy good health ..experience the love of God and their neighbours These aspirations guide our local-level programming strategies as well as national, regional and partnership strategies.