An Interview with New York Bassoonist Leonard Hindell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Opera: a Brief Overview

The Opera: a brief overview Emilio Sala The most reliable experts swear that the opera is the most widely performed in the world. However, when it was first staged at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 3 March 1875, it was given a rather frosty reception. The fact that the public did not understand it was a cause of deep sorrow to Bizet, who died three months later at the age of only thirty-six. Even so, Carmen ran for 48 consecutive performances, which can hardly be considered a negligible figure, although ironically, the audiences were drawn by the opera’s reputed indecency and its condemnation by the press. “Our stages are increasingly invaded by courtesans. This is the class from which our authors so like to re - cruit the heroines of their dramas and their opéras-comiques ”, wrote Achille de Lauzières in his review published in La Patrie on 8 March. He went on: “It is the fille in the most repugnant sense of the word [that has been set on stage]; the fille who is obsessed with her body, who gives herself to the first soldier that passes, on a whim, as a dare, blindly; […] sensual, mocking, hard-faced; miscreant, obedient only to the law of pleasure; […] in short, well and truly a prostitute off the streets”. The critic for the Petit Journal on 6 March said of the interpretation of Carmen: “Madame Galli-Marié has found how to make the character of Carmen more vulgar, more hateful and more abject than it already was in Mérimée. Her interpretation is brutally re - alistic, in the manner of Courbet”. -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

825646078684.Pdf

JOHANNES BRAHMS 1833–1897 Concerto for violin and cello in A minor, Op.102* 1 I Allegro 16.10 2 II Andante 7.39 3 III Vivace non troppo 8.10 FELIX MENDELSSOHN 1809–1847 Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 4 I Allegro molto appassionato 12.28 5 II Andante 7.42 6 III Allegretto non troppo — Allegro molto vivace 6.38 58.47 ITZHAK PERLMAN violin YO-YO MA cello* Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Daniel Barenboim IGOR STRAVINSKY 1882–1971 Violin Concerto in D 7 I Toccata 5.40 8 II Aria I 4.04 9 III Aria II 5.00 10 IV Capriccio 5.52 SERGEI PROKOFIEV 1891–1953 Violin Concerto No.2 in G minor, Op.63 11 I Allegro moderato 10.06 12 II Andante assai 9.15 13 III Allegro, ben marcato 6.13 46.10 ITZHAK PERLMAN violin Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Daniel Barenboim 2 Original album cover 3 he erato & Teldec Recordings Mendelssohn · Prokofiev · Brahms · Stravinsky On these two albums — the Mendelssohn and Prokofiev concertos originally released on Erato, the two others on Teldec — Itzhak Perlman was revisiting repertoire he had first recorded earlier on in his career. He had recorded Prokofiev’s Second Violin Concerto for RCA (with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Erich Leinsdorf) as early as 1966, and Mendelssohn’s Concerto (with the London Symphony Orchestra and André Previn; see volume 5) six years later. He had also gone on to commit a further interpretation of each work to disc: the Prokofiev with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Gennady Rozhdestvensky in 1980 (see volume 29), the Mendelssohn with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Bernard Haitink in 1983 (volume 33). -

Program Notes by Dr

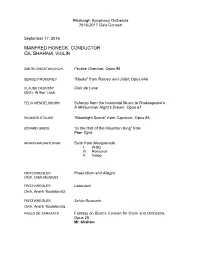

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

University Musical Society

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Chicago Symphony Winds Grover Schiltz, Oboe Daniel Gingrich, Horn Richard Kanter, Oboe Norman Schweikert, Horn Larry Combs, Clarinet Burl Lane, Bassoon John Bruce Yeh, Clarinet William Buchman, Bassoon Sunday Afternoon, April 4, 1993, at 4 p.m. Rackham Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Serenade No. 12 in C minor, K. 388 Mozart Allegro Andante Allegro Eine vergniigliche Musik ..... Alfred Uhl Overture, ziemlich lebhaft, frisch Lustiger Marsch, ruhig bewegt Dudelsack Trepak.sehrrasch INTERMISSION Serenade No. 11 in E-flat major, K. 375 Mozart Allegro maestoso Adagio Allegro The Chicago Symphony Winds are represented by Mariedi Anders Artists Management Inc., San Francisco. U-M freshman Brandon Blazo performed the pre-concert carillon recital. FORTIETH CONCERT OF THE 114TH SEASON THIRTIETH ANNUAL CHAMBER ARTS SERIES PROGRAM NOTES Serenade No. 12 in E-flat major, K. 375 Mozart Mozart wrote this Serenade in Vienna, in October 1781, for six instruments - pairs of clarinets, horns, and bassoons. A few months later he added parts for a pair of oboes and tightened up the form considerably. On November 3, 1781, he wrote to his father that the piece had so pleased the players (of the first version) that to celebrate his name day, "at eleven o'clock at night I was treated to a serenade of my own composition. The six men who played it are poor beggars, but they play very well together. They came to the center of my courtyard, and just as I was about to undress they surprised me most pleasantly with the E-flat chord. [Abridged]" These "social" works are not unlike his symphonies, except that they are usually looser in form and lighter in tone, and they may have extra slow movements or minuets or both. -

Overture Opera Guides

overture opera guides in association with We are delighted to have the opportunity to work with Overture Publishing on this series of opera guides and to build on the work English National Opera did over twenty years ago on the Calder Opera Guide Series. As well as reworking and updating existing titles, Overture and ENO have commissioned new titles for the series and all of the guides will be published to coincide with repertoire being staged by the company at the London Coliseum. We hope that these guides will prove an invaluable resource now and for years to come, and that by delving deeper into the history of an opera, the poetry of the libretto and the nuances of the score, read- ers’ understanding and appreciation of the opera and the art form in general will be enhanced. John Berry Artistic Director, ENO The publisher John Calder began the Opera Guides series under the editorship of the late Nicholas John in association with English National Opera in 1980. It ran until 1994 and eventu- ally included forty-eight titles, covering fifty-eight operas. The books in the series were intended to be companions to the works that make up the core of the operatic repertory. They contained articles, illustrations, musical examples and a complete libretto and singing translation of each opera in the series, as well as bibliographies and discographies. The aim of the present relaunched series is to make available again the guides already published in a redesigned format with new illustrations, some newly commissioned articles, updated reference sections and a literal translation of the libretto that will enable the reader to get closer to the intentions and meaning of the original. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2005

anglewood - ORIGINS GAU€RV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 i^^H^H^H^m Wfi? Burning Tree Estates! " ^fWf —-r- m& II •HI I^Sror HI! an inviting opportunity in the Berkshires: our exclusive community of fifteen [ Comforts of Home ] tastefully unique homes. Classic New duality of Life ] England designs, abundant with luxury [ 5rai"<? of Community ] amenities, are built with the discerning homeowner in mind. Each is majestically sited on private wooded acres along tranquil streets. Please schedule an appointment to explore our distinctive designs and the remaining lots available at Burning Tree Estates. For more information please call lli|-{Si4~3 or visit Burning Tree Road BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA One Hundred and Twenty- Fourth Season, 2004-05 TANGLEWOOD 2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman John F. Cogan, Jr., Vice-Chairman Robert P. O'Block, Vice-Chairman Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman Edward Linde, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Harlan E. Anderson Eric D. Collins Edmund Kelly Edward I. Rudman George D. Behrakis Diddy Cullinane, George Krupp Hannah H. Schneider Gabriella Beranek ex-officio R. Willis Leith, Jr. Thomas G. Sternberg Mark G. Borden William R. Elfers Nathan R. Miller Stephen R. Weber Jan Brett Nancy J. Fitzpatrick Richard P. Morse Stephen R. Weiner Samuel B. Bruskin Charles K. Gifford Ann M. Philbin, Robert C. Winters Paul Buttenwieser Thelma E. Goldbere James F. Cleary Life Trustees Vernon R. -

Carmen Study Guide MANITOBA OPERA GRATEFULLY AKNOWLEDGES OUR CARMEN PARTNERS

2 0 1 9 / 2 0 STUDY GUIDE Production Sponsors MANITOBA OPERA 1 2019/20 Carmen Study Guide MANITOBA OPERA GRATEFULLY AKNOWLEDGES OUR CARMEN PARTNERS: SEASON SPONSOR EDUCATION, OUTREACH, & COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT SPONSORS Student Night at the Opera Sponsor 1060-555 Main Street Winnipeg MB R3B 1C3 Lower Level, Centennial Concert Hall 204-942-7470 | mbopera.ca Join our e-newsletter for exclusive behind-the-scenes content. Just go to mbopera.ca and click “Join our Mailing List.” MANITOBA OPERA 2 2019/20 Carmen Study Guide 2019/20 STUDY GUIDE CARMEN THE PRODUCTION HISTORICAL CONNECTION Fast Facts 4 Historical Background of Carmen 19 Production Information 5 Who are the Roma? 22 Introduction & Synopsis 6 Carmen in the 20th Century 26 The Principal Characters 8 Evolving Perspectives on Carmen 27 The Principal Artists 9 The Composer 14 STUDENT RESOURCES The Librettists 15 Student Activities 28 The Dramatist 16 Winnipeg Public Library Resources 37 Musical Highlights 17 Student Programming 38 Kirstin Chávez (Carmen) and David Pomeroy (Don José). Carmen, 2010. Manitoba Opera. Photo: R. Tinker. MANITOBA OPERA 3 2019/20 Carmen Study Guide THE PRODUCTION FAST FACTS •Even though it is considered by many to be •Traditionally, the tragic tale of Carmen the most popular opera of all time, ends with Don José killing Carmen in a fit had a rocky start, and was not well received of jealousy. Some modern productions have at its premiere. addressed the issue of violence perpetrated against women by altering the ending, in •Rehearsing the opera for its premiere was which Carmen kills Don José in self-defense. -

A Collection of Stan Ruttenberg's Reviews of Mahler Recordings From

A collection of Stan Ruttenberg’s Reviews of Mahler Recordings from the Archives Of the Colorado MahlerFest (Symphonies 3 through 7 and Kindertotenlieder) Colorado MahlerFest XIII Recordings of the Mahler Third Symphony Of the fifty recordings listed in Peter Fülöp’s monumental discography (up to 1955, and many more have been added since then), I review here fifteen at my disposal, leaving out two by Boulez and one by Scherchen as not as worthy as the others. All of these fifteen are recommendable, all with fine points, all with some or more weaknesses. I cannot rank them in any numerical order, but I can say that there are four which I would rather hear more than the others — my desert island choices. I am glad to have the others for their own particular merits. Getting ready for MFest XIII we discovered that the matter of score versions and parts is complex. I use the Dover score, no date but attributed to Universal Edition; my guess this is an early version. The Kalmus edition is copied from who knows which published version. Then there is the “Critical Edition,” prepared by the Mahler Gesellschaft, Vienna. I can find two major discrepancies between the Dover/Universal and the Critical (I) the lack of horns at RN25-5, doubling the string riff and (ii) only two harp glissandi at the middle of RN28, whereas the Critical has three. Our first horn found another. Both the Dover and Critical have the horn doublings, written ff at RN 67, but only a few conductors observe them. -

2000-2001 the Lynn University Philharmonia

The Lynn University Philharmonia Arthur Weisberg, conductbr with special guest Ray Still, oboe and Phillip Evans, piano Paul Green, clarinet Mark Hetzler, trombone Ying Huang, piano Claudio Jaffe, cello Gregory Miller, french horn Johanne Perron, cello Roberta Rust, piano Sergiu Schwartz, violin Arthur Weisberg, bassoon Laura Wilcox, viola 7:30 p.m. November 10, 2000 Spanish River Church PROGRAM Concerto for 3 Keyboards and Orchestra ........... J. S. Bach Allegro (1685-1750) AJagio AUegro Roberta Rwt, piano Phillip Evans, piano Ymg Huang, piano Adagio & Allegro Moho ................................... M. Haydn (for french horn, trombone, iind orchestra) ( 1737-1806) Gregory Miller, french horn Mark Hetzler, trombone Sinfonia Concertante for winds and orchestra .... W. A. Mozart A//egro (1756-1791) AJagio Antlantino con varizioni Ray Still, guest oboist Paul Green, clarinet Arthur Weisberg, bassoon Gregory Miller, french horn INTERMISSION Concerto for Two Cellos ................................... D. Ott Andante tspressivo Andante cantabile Alkgro con brio Johanne Perron, cello Claudio Jaffe, cello Sinfonia Concertante for strings and orchestra .... W. A. Mozart Allegro matstoso (1756-1791) Andante Presto Scrgiu Schwartz, violin laura Wilcox, viola ARTHUR WEISBERG Conductor I Bassoon Arthur Weisberg is considered to be among the world's leading bassoonists. He has played with the Houston, Baltimore, and Cleveland Orchestras, as well as with the Symphony of the Air and the New York Woodwind Quimet. As a music director, Mr. Weisberg has worked with the New Chamber Orchestra of Westchester, Orchestra da Camera (of Long Island, New York}, Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, Orchestra of rhe 20th Century, Stony Brook Symphony, Iceland Symphony, and Ensemble 21. With these various ensembles, he has toured around the world, performing over 100 world premieres and making numerous recordings. -

An Analysis and Discussion of Zwischenfach Voices by Jennifer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository An Analysis and Discussion of Zwischenfach Voices by Jennifer Allen A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Carole FitzPatrick, Co-Chair Kay Norton, Co-Chair Dale Dreyfoos Russell Ryan Robert Barefield ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2012 ABSTRACT Zwischen in the German language means ‘between,’ and over the past century, as operatic voices have evolved in both range and size, the voice classification of Zwischenfach has become much more relevant – particularly to the female voice. Identifying whether nineteenth century composers recognized the growing opportunities for vocal drama, size, and range in singers and therefore wrote roles for ‘between’ singers; or conversely whether, singers began to challenge and develop their voices to sing the new influx of romantic, verismo and grand repertoire is difficult to determine. Whichever the case, teachers and students should not be surprised about the existence of this nebulous Fach. A clear and concise definition of the word Fach for the purpose of this paper is as follows: a specific voice classification. Zwischenfach is an important topic because young singers are often confused and over-eager to self-label due to the discipline’s excessive labeling of Fachs. Rushing to categorize a young voice ultimately leads to misperceptions. To address some of the confusion, this paper briefly explores surveys of the pedagogy and history of the Fach system. To gain insights into the relevance of Zwischenfach in today’s marketplace, I developed with my advisors, colleagues and students a set of subjects willing to fill out questionnaires. -

Chicago on the Aisle 147 CHICAGO STUDIES

Chicago on the Aisle 147 CHICAGO STUDIES Claudia Cassidy’s Music Criticism and Legacy HANNAH EDGAR, AB’18 Introduction Criticism of value is not a provincial art. It has nothing whatever to do with patting undeserving heads, hailing earnest mediocrities as geniuses, or groveling in gratitude before second-rate, cut-down or broken-down visitors for fear they might not come again. It is neither ponderous nor pedantic, virulent nor hysterical. Above all, it is not mean-spirited. Ten what is it? Ideally, criticism is informed, astute, inquisitive, candid, interesting, of necessity highly personal. Goethe said, “Talent alone cannot make a writer. Tere must be a man behind the book.” Tere must be a person behind the critic. Nobody reads a nobody. Unread criticism is a bit like an unheard sound. For practical purposes it does not exist. — Claudia Cassidy 1 1. Claudia Cassidy, “Te Fine Art of Criticism,” Chicago, Winter 1967, 34. THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO 148 In June 1956, Chicago magazine ran an eye-catching cover story. A castle composed of colorful shapes, as though rendered through collage, overlap over a parchment-white backdrop. In the form of one of the shapes is a black-and-white photo of a woman of indeterminate age: fair-faced, high cheekbones, half-lidded eyes, a string of pearls around her neck and a Mona Lisa smile on her lips. She is named, coronated, and damned in one headline: “Claudia Cassidy: Te Queen of Culture and Her Reign of Terror.”2 When Bernard Asbell wrote this profle, Clau- dia Cassidy was the chief music and drama critic of the Chicago Tribune and at the height of her career.