Ethnic Groups in Zagreb's Gradec in the Late Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formalising Aristocratic Power in TAYLOR Accepted GREEN

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/S0080440118000038 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Taylor, A. (2018). Formalising aristocratic power in royal acta in late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century France and Scotland . Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 2018(28), 33-64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440118000038 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

The Uncrowned Lion: Rank, Status, and Identity of The

Robert Kurelić THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner Budapest May 2005 I, the undersigned, Robert Kurelić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 May 2005 __________________________ Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________1 ...heind graffen von Cilli und nyemermer... _______________________________ 1 ...dieser Hunadt Janusch aus dem landt Walachey pürtig und eines geringen rittermessigen geschlechts was.. -

Oligarchs, King and Local Society: Medieval Slavonia

Antun Nekić OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May2015 OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest Month YYYY OLIGARCHS, KING AND LOCAL SOCIETY: MEDIEVAL SLAVONIA 1301-1343 by Antun Nekić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY I, the undersigned, Antun Nekić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. -

About the Counts of Cilli

ENGLISH 1 1 Old Castle Celje Tourist Information Centre 6 Defensive Trench and Drawbridge ABOUT THE COUNTS OF CILLI 2 Veronika Café 7 Tower above Pelikan’s Trail 3 Eastern Inner Ward 8 Gothic Palatium The Counts of Cilli dynasty dates back Sigismund of Luxembourg. As the oldest 4 Frederick’s Tower (panoramic point) 9 Romanesque Palatium to the Lords of Sanneck (Žovnek) from son of Count Hermann II of Cilli, Frederick 5 Central Courtyard with a Well 10 Viewing platform the Sanneck (Žovnek) Castle in the II of Cilli was the heir apparent. In the Lower Savinja Valley. After the Counts of history of the dynasty, he is known for his Heunburg died out, they inherited their tragic love story with Veronika of Desenice. estate including Old Castle Celje. Frederick, His politically ambitious father married 10 9 Lord of Sanneck, moved to Celje with him off to Elizabeth of Frankopan, with 7 his family and modernised and fortified whom Frederick was not happy. When his the castle to serve as a more comfortable wife was found murdered, he was finally 8 residence. Soon after, in 1341, he was free to marry his beloved but thus tainted 4 10 elevated to Count of Celje, which marks the the reputation of the whole dynasty. He beginning of the Counts of Cilli dynasty. was consequently punished by his father, 5 6 The present-day coat-of-arms of the city who had him imprisoned in a 23-metre of Celje – three golden stars on a blue high defence tower and had Veronika background – also dates back to that period. -

Asions of Hungarian Tribes

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / CZECH REPUBLIC Date Country | Description 833 A.D. Czech Republic The establishment of Great Moravia (Moravia, western Slovakia, parts of Hungary, Austria, Bohemia and Poland). 863 A.D. Czech Republic Spread of Christianity, arrival of missionaries Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius; establishment of Old Slavonic language, Glagolitic script. Archbishopric established. Conflicts with Frankish empire, invasions of Hungarian tribes. The foundation of Prague Castle. 965 A.D. Czech Republic Prague described in narration of Jewish-Arabian merchant Ibn Jákúb. Establishment of first (Benedictine) monasteries and Prague bishopric (974). Foundation of the Czech state under the Przemyslid dynasty. 1031 A.D. Czech Republic Origination of the Moravian Margraviate as part of the Czech state, with main centres Znojmo, Brno and Olomouc. 1063 A.D. Czech Republic Founding of Olomouc bishopric. Vratislav II made first Czech King (1085). The first Czech chronicle known as the Chronicle of Cosmas. Premonstratensian and Cistercian monasteries founded (1140). 1212 A.D. Czech Republic Golden Bull of Sicily: Roman King Friedrich II defines the relationship between Czech kings and the Holy Roman Empire. The Czech king becomes one of seven electors privileged to elect the Roman king. 1234 A.D. Czech Republic Establishment of towns. German colonisation. Invasion of the Mongolians (1241). Introduction of mining law (1249), the provincial court (1253) and provincial statutes. The Inquisition introduced (1257). 1278 A.D. Czech Republic P#emysl Otakar II killed at Battle of the Moravian Field. Under his rule, the Czech lands reached to the shores of the Adriatic. Bohemia governed by Otto of Brandenburg, Moravia by Rudolph of Habsburg. -

Hellozagreb5.Pdf

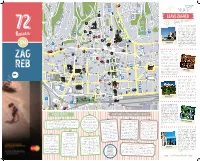

v ro e H s B o Šilobodov a u r a b a v h Put o h a r r t n e e o i k ć k v T T c e c a i a i c k Kozarčeve k Dvor. v v W W a a a Srebrnjak e l Stube l St. ć č Krležin Gvozd č i i s ć Gajdekova e k Vinogradska Ilirski e Vinkovićeva a v Č M j trg M l a a a Zamen. v č o e Kozarčeva ć k G stube o Zelengaj NovaVes m Vončinina v Zajčeva Weberova a Dubravkin Put r ić M e V v Mikloušić. Degen. Iv i B a Hercegovačka e k Istarska Zv k u ab on ov st. l on ar . ić iće Višnjica . e va v Šalata a Kuhačeva Franje Dursta Vladimira Nazora Kožarska Opatička Petrova ulica Novakova Demetrova Voćarska Višnjičke Ribnjak Voćarsko Domjanićeva stube naselje Voćarska Kaptol M. Slavenske Lobmay. Ivana Kukuljevića Zamenhoova Mletač. Radićeva T The closest and most charming Radnički Dol Posil. stube k v Kosirnikova a escape from Zagreb’s cityŠrapčeva noise e Jadranska stube Tuškanac l ć Tuškanac Opatovina č i i is Samobor - most joyful during v ć e e Bučarova Jurkovićeva J. Galjufa j j Markov v the famous Samobor Carnival i i BUS r r trg a Ivana Gorana Kovačića Visoka d d andJ. Gotovca widely known for the cream Bosanska Kamenita n n Buntićeva Matoševa A A Park cake called kremšnita. Maybe Jezuitski P Pantovčak Ribnjak Kamaufova you will have to wait in line to a trg v Streljačka Petrova ulica get it - many people arrive on l Vončinina i Jorgov. -

Sweet September

MARK YOUR MAPS WITH THE BEST OF MARKETS * Agram German exonym its Austrian by outside Croatia known commonly more was Zagreb LIMITED EDITION INSTAGRAM* FREE COPY Zagreb in full color No. 06 SEPTEMBER ast month, Zagreb was abruptly left without Dolac. 2015. LFor one week, stalls and vendors migrated to Ban Jelačić Square, only to move back to their original place, but now repaved, refurbished and in full color again. The Z ‘misplaced’ Dolac was a unique opportunity to be remind- on Facebook ed of what things were like half a century ago. This month 64-second kiss there is another time-travel experience on Jelačić Square: on the world’s Vintage Festival in the Johann Franck cafe, taking us shortest funic- back to the 50s and 60s. Read more about it in this issue... ular ride The world’s shortest funicular was steam-powered Talkabout until 1934. The lower stop on Croatia Tomićeva Street GRIČ-BIT IS BACK! connects with the upper stop on The fifth edition of the the Strossmayer best street festival kicks promenade, off on the first day of in front of the ANJA MUTIĆ fall, joining forces with Lotršćak Tower. Author of Lonely Planet Croatia, writes for New the ‘At the Upper Town’ As the Zagreb York Magazine and The Washington Post. Follow her at @everthenomad initiative and showcas- oldest means of public transport, ing Device_art work- the funicular shops and exhibitions began operating Sweet hosted by Space Festival only a year and the Klovićevi Dvori before the horse- gallery. All this topped drawn tram. -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

Medical Care in Ancient Zagreb

45(6):669-670,2004 COVER PAGE Medical Care in Ancient Zagreb Zagreb is the capital of the Republic of Croatia, cate that the order probably maintained a school. In- the heart of all Croats wherever they may be, replete timidated by the Turkish expansion at the end of the with monuments and artifacts that attest to its long 15th century, the Dominicans slowly abandoned and intriguing history. As bishops’ sees were always their unprotected abode and moved into the fortified established alongside major population centers, the nearby “free and royal town Gradec of Zagreb.” The town must have existed even before 1094 A.D., when abandoned property was demolished between 1512 King Ladislaus established the diocese of Zagreb. Ar- and 1520 when Thomas Bakaè, Archbishop of Ester- cheological evidence shows that the area has been gon and Rector of the Diocese of Zagreb, protected settled from the older Iron Age (7th century B.C.) the cathedral by an imposing fortress containing six through Roman period and early Christian era to mo- circular and two square towers in early Renaissance dernity (1). style (4). In the Middle Ages, Zagreb occupied two adja- After the Tatars retreated, Gradec did not fall be- cent hills separated by a stream. The bishop and the hind Kaptol in building – the three-nave Romanesque canons occupied the eastern hill; hence its current St. Mark’s parochial Church was built on the central name of Kaptol (Capitol, the house of canons). Mer- St. Mark’s square at about the same time as the St. Ste- chants and artisans dwelled on the western hill. -

Investicijski Potencijali Hrvatske

KONFERENCIJA INVESTICIJSKI POTENCIJALI HRVATSKE Srijeda, 23. travnja 2014. Kristalna dvorana Hotel Westin Zagreb ...About Croatia... ...o Hrvatskoj... Republika Hrvatska sredn-joeuropska The Republic of Croatia is a Central ...o Hrvatskoj... 3 ...o Hrvatskoj... je i mediteran-ska zemlja. Doseljenjem European and Medi-terranean county. na današnji hrvatski prostor u 7. The Croats settled on the today’s Tomislav Karamarko 6 Tomislav Karamarko stoljeću, na prostor od Jadranskog Croatian territory in the 7th century, Predsjednik HDZ-a President of HDZ mora do Drave i Dunava, Hrvati su u in the area between the Adri-atic Sea on Srećko Prusina 10 Srećko Prusina novoj domovini asimilirali stečevine one side, and the Drava and the Danube rimske, helenske i bizantske civilizacije, on the other. Croats assimilated Ro- Klaus-Peter Willsch 12 Klaus-Peter Willsch očuvavši svoj jezik i zajedništvo. Već od man, Hellenistic and Byzantine heritage ranog srednjeg vijeka, u doba narodne in their new home-land, preserving prof.dr.sc. Krunoslav Zmaić 14 Krunoslav Zmaić, PhD dinastije Trpimirovića, kao jedna od their language and unity. Ever since najstarijih europskih država, Hrvatska the early Middle Ages and the times trajno pripada katoličkom i kršćanskom of Trpimirović Dynasty, Croatia has, as Marija Tufekčić 17 Marija Tufekčić za-padu. Tijekom tog vremena Hrvati one of the oldest Eu-ropean countries, su, uz standarni latin-ski jezik u permanently belonged to catholic and Zdravko Krmek 18 Zdravko Krmek diplomatičkim is-pravama, koristili i Chris-tian West. In that time Croats hrvatski, pisan uglatom glagoljicom, used standard Latin language in Zlatko Rogožar 20 Zlatko Rogožar kroz koju se sačuvao ne samo jezik, diplomatic documents, but Croatian već i drevna pučka duhovnost. -

Medieval Biography Between the Individual and the Collective

Janez Mlinar / Medieval Biography Between the individual and the ColleCtive Janez Mlinar Medieval Biography between the Individual and the Collective In a brief overview of medieval historiography penned by Herbert Grundmann his- torical writings seeking to present individuals are divided into two literary genres. Us- ing a broad semantic term, Grundmann named the first group of texts vita, indicating only with an addition in the title that he had two types of texts in mind. Although he did not draw a clear line between the two, Grundmann placed legends intended for li- turgical use side by side with “profane” biographies (Grundmann, 1987, 29). A similar distinction can be observed with Vollmann, who distinguished between hagiographi- cal and non-hagiographical vitae (Vollmann, 19992, 1751–1752). Grundmann’s and Vollman’s loose divisions point to terminological fluidity, which stems from the medi- eval denomination of biographical texts. Vita, passio, legenda, historiae, translationes, miracula are merely a few terms signifying texts that are similar in terms of content. Historiography and literary history have sought to classify this vast body of texts ac- cording to type and systematize it, although this can be achieved merely to a certain extent. They thus draw upon literary-historical categories or designations that did not become fixed in modern languages until the 18th century (Berschin, 1986, 21–22).1 In terms of content, medieval biographical texts are very diverse. When narrat- ing a story, their authors use different elements of style and literary approaches. It is often impossible to draw a clear and distinct line between different literary genres. -

The Short Outline of the History of the Czech Lands in The

Jana Hrabcova 6th century – the Slavic tribes came the Slavic state in the 9th century situated mostly in Moravia cultural development resulted from the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius – 863 translation of the Bible into the slavic language, preaching in slavic language → the Christianity widespread faster They invented the glagolitic alphabet (glagolitsa) 885 – Methodius died → their disciples were expeled from G.M. – went to Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia etc., invented cyrilic script http://www.filmcyrilametodej.cz/en/about-film/ The movie (document) about Cyril and Methodius the centre of the duchy in Bohemia Prague the capital city 10th century – duke Wenceslaus → assassinated by his brother → saint Wenceslaus – the saint patron of the Czech lands the Kingdom of Bohemia since the end of 12th century Ottokar II (1253–1278, Přemysl Otakar II) – The Iron and Golden King very rich and powerful – his kingdom from the Krkonoše mountains to the Adriatic sea 1278 – killed at the battle of Dürnkrut (with Habsburgs) Wenceslaus II of Bohemia (1278–1305) – king of Bohemia, King of Poland Wenceslaus III (1305–1306) – assassinated without heirs The kingdom of Ottokar II The Kingdom of Wenceslaus II Around 1270 around 1301 John of Bohemia (1310–1346, John the Blind) married Wenceslaus’s sister Elizabeth (Eliška) Charles IV the king of Bohemia (1346–1378) and Holy Roman Emperor (1355–1378) . The Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) – an empire existing in Europe since 962 till 1806, ruled by Roman Emperor (present –day territories of Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Switzerland and Liechenstein, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia, parts of eastern France, nothern Italy and western Poland) the most important and the best known Bohemian king 1356 - The Golden Bull – the basic law of the Holy Roman Empire Prague became his capital, and he rebuilt the city on the model of Paris, establishing the New Town of Prague (Nové Město), Charles Bridge, and Charles Square, Karlštejn Castle etc.