Nigeria Final Book2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Gowon, Babangida and Abacha Regimes

University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES by SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULTY OF HUMAN SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA January 2001 University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. My deepest gratitude to: Mr. J.T. Bekker for his guidance; Dr. Funmi Olonisakin for her advice, Estrellita Weyers for her numerous searches for sources; and last but not least, my wife Estia-Marié, for her constant motivation, support and patience. This dissertation is dedicated to the children of Africa, including my firstborn, Marco Hoogenraad-Vermaak. ii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S “General Abacha wasn’t the first of his kind, nor will he be last, until someone can answer the question of why Africa allows such men to emerge again and again and again”. BBC News 1998. Passing of a dictator leads to new hope. 1 Jul 98. iii University of Pretoria etd - Hoogenraad-Vermaak, S SUMMARY THE ENVIRONMENT DETERMINED POLITICAL LEADERSHIP MODEL: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GOWON, BABANGIDA AND ABACHA REGIMES By SALOMON CORNELIUS JOHANNES HOOGENRAAD-VERMAAK LEADER: Mr. J.T. BEKKER DEPARTMENT: POLITICAL SCIENCE DEGREE FOR WHICH DISSERTATION IS MAGISTER ARTIUM PRESENTED: POLITICAL SCIENCE) The recent election victory of gen. -

Politics in Nigeria: a Discourse of Osita Ezenwanebe’S ‘Giddy Festival’

Humanitatis Theoreticus Journal, Vol. 1(1) (2018) (Original paper) O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Theatre Politics in Nigeria: A Discourse of Osita Ezenwanebe’s ‘Giddy Festival’ Philip Peter Akoje Department of Theatre Arts, Kogi State University, Ayigba. Email: [email protected] Phone Number: +2347039781766 Abstract Politics is a vital aspect of every society. This is due to the fact that the general development of any country is first measured by its level of political development. Good political condition in a nation is a sine qua non to economic growth. A corrupt and unstable political system in any country would have a domino-effect on the country's economic outlook and social lives of the people. The concept of politics itself continued to be interpreted by many political scholars, critics and the masses from different perspectives. Corruption, political assassination, greed, perpetrated not only by politicians but also by the masses are the societal ills that continue to militate against socio-economic and political development in most African countries, particularly Nigeria. Peaceful political transition to the opposition party in Nigeria in recent times has given a different dimension to the country’s political position for other countries in the region to emulate. This paper addresses the concept of politics and presents corruption in Nigerian society from the point of theatre, using Osita Ezenwanebe’s Giddy Festival. The investigation is grounded in sociological theory and the concept of political realism. This paper recommends that politics can be violent-free if all the actors in the game develop selfless qualities of leadership for the benefit of the ruled. -

The Brides of Boko Haram: Economic Shocks, Marriage Practices, and Insurgency in Nigeria∗

The Brides of Boko Haram: Economic Shocks, Marriage Practices, and Insurgency in Nigeria∗ Jonah Rexery University of Pennsylvania January 9, 2019 Abstract In rural Nigeria, marriage markets are characterized by the customs of bride-price – pre-marital payments from the groom to the family of the bride – and polygamy – the practice of taking more than one wife. These norms can diminish marriage prospects for young men, causing them to join violent insurgencies. Using an instrumental variables strategy, I find that greater inequality of brides among men increases the incidence of militant activity by the extremist group Boko Haram. To instrument for village-level marriage inequality, I exploit the fact that young women delay marriage in response to good pre-marital economic conditions, which increases marriage inequality more in polygamous areas. Supporting the mechanism, I find that the same positive female income shocks which increase marriage inequality and extremist activity also reduce female marriage hazard, lead women to marry richer and more polyga- mous husbands, generate higher average marriage expenditures, and increase abductions and violence against women. The results shed light on the marriage market as an important but hitherto neglected driver of violent extremism. JEL Classifications: D74, J12, Z12, Z13 Keywords: marriage market, traditional cultural practices, extremism, conflict, income shocks ∗For their insightful comments, I thank Camilo Garcia-Jimeno, Guy Grossman, Nina Harrari, Santosh Anagol, Cor- rine Low, Robert Jensen, -

(UK), FICMC, CEDR International Accredited Mediator Abuja, Nigeria [email protected] TEL: +2348033230207

DR DINDI, NTH NURAEN T.H. DINDI ESQ. PhD, LL.M, BL, AClarb (UK), FICMC, CEDR International Accredited Mediator Abuja, Nigeria [email protected] TEL: +2348033230207 SUMMARY: To develop a professional career while making positive contribution to the success of a dynamic organization that recognizes and encourages diligence, integrity, and honesty. BIODATA: Date of Birth: 17TH November, 1958 Place of Birth: Lagos Island Nationality: Nigerian State of Origin: Ogun State Local Government Area: Abeokuta North Marital Status: Married Permanent Home Address 42, Ibukun Street, Surulere, Lagos EDUCATION: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Islamic Law February, 2012 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State Masters in Law (LL.M), Islamic Law December, 1998 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State B.L (SCN 007995A) October, 1986 Nigeria Law School, Lagos Bachelor of Law (LL.B {Comb. Hons}, Islamic & Common Law) July, 1984 University of Sokoto (now Usman Dan Fodio), Sokoto Higher School Certificate (H.S.C) June, 1980 Federal School of Art & Science, Sokoto West African School Certificate (WASC) June, 1976 Ansar-Ud-Deen College, Isolo, Lagos First School Leaving Certificate (FSLC) December, 1971 Salvation Army Primary School, Surulere, Lagos Fellow (FICMC) November, 2017 Institute of Chartered Mediators and Conciliators (ICMC), Nigeria. DR DINDI, NTH Associate Member (ChMc) November, 2010 Institute of Chartered Mediators and Conciliators (ICMC), Nigeria. CEDR 2013 International Accredited Mediator NCMG International /CEDR Mediation Accreditation, -

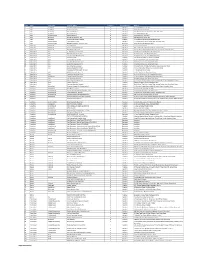

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

Patriarchy: a Driving Force for the Abuse of Reproductive Rights of Women in Nigeria

www.ijird.com February, 2016 Vol 5 Issue 3 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Patriarchy: A Driving Force for the Abuse of Reproductive Rights of Women in Nigeria Felicia Anyogu Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria B. N. Okpalobi Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Abstract: Reproductive health is a state of complete psychological, physical and social well-being of individuals and reproductive health rights means that everyone has the right to integral well-being in reproductive concerns. This further implies people have the right to practice sexual relationships, reproduce, regulate their fertility, enjoy sexual relationships and protection against sexually transmitted diseases and so on. Women in Nigeria are in every context socially, economically, legally and culturally disadvantaged as a result of the deep patriarchal nature of the Nigerian society. Patriarchy is also the root of the cultural norms and traditions which are all forms of abuse of the reproductive rights of women. This paper looks at patriarchy as the root of the subjugation of women in Nigeria and analyses its overriding effect on all the factors that militate against the reproductive rights of women. Recommendations that will make a positive change if adhered to, shall also be proffered. Keywords: Patriarchy, abuse, reproductive rights, women, Nigeria. 1. Introduction The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999) in Chapter IV guarantees the Right to Life (S. 33) to all citizens. The enjoyment of good health, and by extension reproductive health is incidental on right to Life but these are not guaranteed as of right by the Constitution since they are not presented as fundamental. -

Introduction 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South

Notes Introduction 1. Kwame Nkrumah, Towards Colonial Freedom: Africa in the Struggle against World Imperialism, London: Heinemann, 1962. Kwame Nkrumah was the first president of Republic of Ghana, 1957–1966. 2. J.M. Roberts, History of the World, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 425. For further details see Leonard Thompson, A History of South Africa, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990, pp. 31–32. 3. Douglas Farah, “Al Qaeda Cash Tied to Diamond Trade,” The Washington Post, November 2, 2001. 4. Ibid. 5. http://www.africapolicy.org/african-initiatives/aafall.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 6. G. Feldman, “U.S.-African Trade Profile.” Also available online at: http:// www.agoa.gov/Resources/TRDPROFL.01.pdf. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 7. Ibid. 8. Salih Booker, “Africa: Thinking Regionally, Update.” Also available online at: htt://www.africapolicy.org/docs98/reg9803.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2004. 9. For full details on Nigeria’s contributions toward eradication of the white minority rule in Southern Africa and the eradication of apartheid system in South Africa see, Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigerian Foreign Policy under Military Rule, 1966–1999, Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003, pp. 79–93. 10. See Olayiwola Abegunrin, Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of Zimbabwe: A Study of Foreign Policy Decision Making of an Emerging Nation. Stockholm, Sweden: Bethany Books, 1992, p. 141. 1 Nigeria and the Struggle for the Liberation of South Africa 1. “Mr. Prime Minister: A Selection of Speeches Made by the Right Honorable, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa,” Prime Minister of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Lagos: National Press Limited, 1964, p. -

Commonwealth Secretary-General

-S7P' COMMONWEALTH SECRETARY-GENERAL C •,-•;• H. E. Chief Emeka Anyaoku, C.O.N. 16 February 2000 As you might recall, the United Nations and the Commonwealth Secretariat have worked in close D-operation to advance the status of wqmen worldwide. !n 1995, the Commonwealth P!an of Action on Gender and Development (1995-2000) was presented at the Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing as a special Commonwealth contribution to the UN Process. We would similarly like to have our recently endorsed Update to the Commonwealth Plan of Action on Gender and Development (2000-2005) presented and spoken to as a Commonwealth contribution to the Special Session of the UN Assembly on the Beijing Platform for Action set for 5-9 June 2000. To this end, the Commonwealth Ministers Responsible for Women sent a special message to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in South Africa in November 1999, asking for approval of its presentation as the Commonwealth's contribution to the UN General Assembly. This was soundly endorsed at CHOGM. My successor as Secretary-General, the Rt. Hon. Don McKinnon will take up post in April. We would like to ensure that we put all procedures into place so that this Update can be presented by him as a Commonwealth contribution to the UN process in June. My staff from the Secretariat will be attending the Preparatory meetings of the Commission for Status of Women and the PrepCom for the Special Session, seeking through your Division for the Advancement of Women, the best means of achieving this. -

Law Reform in the Muslim World: a Comparative Study of the Practice and Legal Framework of Polygamy in Selected Jurisdictions

International Journal of Business & Law Research 2(3):32-44, September 2014 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2014 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2360-8986 LAW REFORM IN THE MUSLIM WORLD: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE PRACTICE AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF POLYGAMY IN SELECTED JURISDICTIONS YELWA, Isa Mansur Ph. D Researcher, Postgraduate & Research, Ahmad Ibrahim Kulliyyah of Laws, International Islamic University, 53100, Jln Gombak, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia H/P +60166194962 (Malaysia) +2348068036959 (Nigeria) Email of corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper studies the framework of family law in general and of polygamy in particular in the various jurisdictions around the Muslim world. The chronicles in the application of Islamic law in relation to polygamy in those jurisdictions are comparatively analyzed based on historical developments of their legal systems on the application of Islamic law and reforms that were introduced therein to suit the needs and challenges of legal dynamism based on suitability with the people, place and time. Jurisdictions within the sphere of the study are categorized into three, namely: 1. Jurisdictions where polygamy is practiced without regulation; 2. Jurisdictions where polygamy is outlawed; and 3. Jurisdictions where polygamy is practiced under a regulated framework. For each category, a number of relevant jurisdictions are selected for study. The legal framework on polygamy in the selected jurisdictions is briefly elaborated with precision based on the applicable statutory and judicial authorities available. The social set up of the people involved in polygamy in some jurisdictions is illustrated where needed in order to unveil the legal challenges in them. For each jurisdiction, the study examines the law that applied before, subsequent reforms that were brought into them and the contemporary applicable law and its challenges if any. -

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES Key: SO = Sue Onslow (Interviewer) EA = Chief Emeka Anyaoku (Respondent) M = Mary Mackie (Chief Emeka Anyaoku’s Personal Assistant) SO: This is Sue Onslow talking to Chief Emeka Anyaoku on Wednesday, 2nd October, 2013. Chief, thank you very much indeed for coming back to Senate House to talk to me for this project. I wonder if you could begin, please sir, by talking about the preparatory process leading up to the Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings. EA: Well, the Secretariat does essentially three things. First, it consults on a continuous basis with the host government on arrangements and logistics for the meeting. And second, it prepares the preliminary draft agenda in the form of suggestions to governments for their comments and additions if they felt necessary; and then in the light of that, prepares memoranda on the issues involved in the agenda. And then thirdly, it also considers what possible controversies, what possible challenges, particular heads of government meeting will face, and deals with those by consulting the governments concerned and talking to heads who are likely to be involved in resolving what the challenges are. And I must also add to the first point about consulting with the host government that since 1973, when the retreat was introduced, the consultation would also include arrangements for the Retreat. SO: So having identified the host government, then there is close coordination with the Secretariat to ensure the administrative arrangements are as