Music of Sarah Weaver and Collaborations (2006–2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

New Original Works Festival 2009 Program Two

NEW ORIGINAL WORKS FESTIVAL 2009 PROGRAM TWO July 30 – August 1, 2009 8:30pm presented by REDCAT Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater California Institute of the Arts NOW FESTIVAL 2009: PROGRAM TWO NEW ORIGINAL WORKS FESTIVAL 2009 UPCOMING PERFORMANCES August 6 – August 8 : Program Three 1 CAROLE KIM W/ OGURI, ALEX CLINE AND DAN CLUCAS: N Zackary Drucker / Mariana Marroquin / Wu Ingrid Tsang: PIG direction and video installation: Carole Kim Meg Wolfe: Watch Her (Not Know It Now) dance: Oguri Lauren Weedman: Off percussion: Alex Cline winds: Dan Clucas live-feed video: Adam Levine and Moses Hacmon lighting design: Chris Kuhl I. Reflect --he vanishes Into the skin of water... ...And leaves me with my arms full of nothing But water and the memory of an image? ...The one I loved should be let live. He should live on after me, blameless.’ [Tales from Ovid, Hughes] II. Hall of Mirrors The black mirror is a surface, but this surface is also a depth. This specular catastrophe, prefigured by the myth of Narcissus, is inseparable from a process that renders the gaze opaque. [The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art, Arnaud Maillet] III. Syphon IV. Shade This mirror creates, as it were, a hole in the wall, a door into the realm of the dead. But it also constitutes an epiphany, since the divinity is seen in all its glory and clarity. [Maillet] Improvising … hinges on one’s ability to synchronize intention and action and to maintain a keen awareness of, sensitivity to, and connection with the evolving group dynamics and experiences. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

NYC Jazz Record

execution. Added inventiveness is found on Dresser’s GLOBE UNITY: BRAZIL composition “Yeller Grace”, which blends “Yellow Rose of Texas”, “Amazing Grace” and the National Anthem into a barely recognizable yet fully engaging mix. And they show plenty of versatility, as piano and bass converse equally well within the sweeping, legato passages of “For My Mother” or the jarring, playful bounces of “Big Mama”. But the true highlight is their interplay on Dresser’s composition “Mattress on a Stick”, which leads with a breathtakingly lyrical bass introduction, over Moser’s sparse and haunting choice Patience of chords. Each tune was recorded straight to two Stéphane Kerecki/John Taylor (Zig-Zag Territoires) entirely clean, un-mixed tracks, the depth of the tones All Strung Out astounding, providing a truly intimate experience. Piano Masters Series, Vol. 2 Denman Maroney/Dominic Lash (Kadima Collective) Philippe Baden Powell (Adventure Music) Duetto Mark Dresser/Diane Moser (CIMP) For more information, visit outhere-music.com/zigzag, Tempo (feat. Eddie Gomez) Tania Maria (Naïve) by Sam Spokony kadimacollective.com and cimprecords.com. Moser and Constelação Brazilian Trio (Motéma Music) In these three albums, we find each piano/bass duo Dresser are at Cornelia Street Café Sep. 6th. See Calendar. by Tom Greenland approaching the world of free improvisation with The world’s fifth largest country, home of bossa different modes of thought and intensity. nova, samba and birthplace of Tom Jobim, Airto Patience, by French bassist Stéphane Kerecki and Moreira, Milton Nascimento and Hermeto Pascoal British pianist John Taylor, reveals the strong influence (to name only a few), Brazil has deeply impacted of the classic dynamic that once existed between jazz. -

Geomungo Factory

★★★★★ PAMS CHOICE in Korea 2010 WOMEX Official Showcase in Greece 2012 ROSKILDE FESTIVAL in Denmark 2013 WORLD MUSIC ENSEMBLE GEOMUNGO FACTORY PHOTO BY EUNYOUNG KIM Five-star rating ★★★★★ LONDON EVENING STANDARD “Whatever you call it, it is original, powerful and thrilling. And certainly like nothing you have ever heard before.” Simon Broughton Top of world music magazine <SONGLINES> 3 GEOMUNGO FACTORY What makes Korea so special is the way it respects its distinctive past, while staying at the cutting edge of technology and innovation – and if there’s one group that sums that up in music, it’s Geomungo Factory (which is pronounced Ko-mungo Factory). The geomungo zither is over a thousand years old and you won’t fine an instrument like it anywhere else in the world. It has six silk strings and is played by hitting and pluking them with a short stick, giving it a deep, muscular sound, both rhythmic and melodic. Geomungo Factory have also created new instrument – the ‘Xylophone geomungo’, ‘the cello geomungo’ and the ‘electric geomungo’ with a wah-wah pedal. Like Konono No. 1 from Congo and Hanggai from Mongolia, Geomungo Factory sound ancient and contemporary at the same time. Geomungo Facoty includes three geomungo players, Yoo Mi-young, Jung Ein-ryoung and Lee Jung-seok, who are all traditional players, plus Kim Sun-a, who plays gayageum, the plucked zither with 18 or more strings, which is more commomly heard in Korea than the geomungo. “Most people think traditional music is boring,“ they say, “so we want to make geomungo music that -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Jason Adasiewicz's Rolldown Varmint Cuneiform 2009

WHAT THE PRESS HAS SAID ABOUT: JASON ADASIEWICZ’S ROLLDOWN VARMINT CUNEIFORM 2009 Line-up: Jason Adasiewicz (vibraphone), Josh Berman (cornet), Aram Shelton (alto saxophone & clarinet), Jason Roebke (bass), Frank Rosaly (drums) “Consult the jazz vibraphone flow chart and it’s easy to connect the dots between major players from Lionel Hampton to Milt Jackson up through Bobby Hutcherson. … Chicago-based Jason Adasiewicz is a relatively new addition to the playing field…the caliber of his work so far certainly places him in a position for early consideration. Varmint continues the course set by his working ensemble Rolldown on their self-titled debut… Apt comparisons to Sixties Blue Note-era Hutcherson have been plentiful in press in describing both Adasiewicz’s sound and his spacious composing style which embraces freer interplay without abandoning an underlying allegiance to head-solos orthodoxy for too long. A closer cousin still might be …Walt Dickerson. Adasiewicz generates a similarly warm and luminous sonority with his mallets and makes regular use of his instrument’s motor to blur his clusters into vivid watercolor shades. The rest of the group is comparably equipped on the creative front with cornetist Josh Berman and alto saxophonist Aram Shelton … obvious antecedents for Shelton are Eric Dolphy and Jackie McLean… Berman has a full range of tonal effects… Bassist Jason Roebke and drummer Frank Rosaly work in keen collusion…The balance is particularly effective … … Chicago residents and visitors are fortunate… Adasiewicz and his colleagues sit well with the city’s fastest company and still have plenty to say.” - Derek Taylor, Dusted, December 2, 2009, www.dustedmagazine.com “Vibraphonist-composer Jason Adasiewicz returns to the same avant-leaning territory he staked out on Rolldown’s eponymous debut in 2008. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

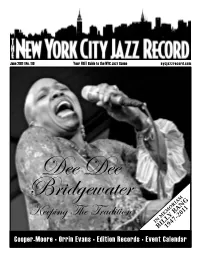

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

The Musical Kinetic Shape: a Variable Tension String Instrument

The Musical Kinetic Shape: AVariableTensionStringInstrument Ismet Handˇzi´c, Kyle B. Reed University of South Florida, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tampa, Florida Abstract In this article we present a novel variable tension string instrument which relies on a kinetic shape to actively alter the tension of a fixed length taut string. We derived a mathematical model that relates the two-dimensional kinetic shape equation to the string’s physical and dynamic parameters. With this model we designed and constructed an automated instrument that is able to play frequencies within predicted and recognizable frequencies. This prototype instrument is also able to play programmed melodies. Keywords: musical instrument, variable tension, kinetic shape, string vibration 1. Introduction It is possible to vary the fundamental natural oscillation frequency of a taut and uniform string by either changing the string’s length, linear density, or tension. Most string musical instruments produce di↵erent tones by either altering string length (fretting) or playing preset and di↵erent string gages and string tensions. Although tension can be used to adjust the frequency of a string, it is typically only used in this way for fine tuning the preset tension needed to generate a specific note frequency. In this article, we present a novel string instrument concept that is able to continuously change the fundamental oscillation frequency of a plucked (or bowed) string by altering string tension in a controlled and predicted Email addresses: [email protected] (Ismet Handˇzi´c), [email protected] (Kyle B. Reed) URL: http://reedlab.eng.usf.edu/ () Preprint submitted to Applied Acoustics April 19, 2014 Figure 1: The musical kinetic shape variable tension string instrument prototype. -

Longer Bio August 2018

Miya Masaoka is a composer and artist based in New York City. Classically trained, her work operates at the intersection of spatialized sound, frequency and perception, performance, social and historical references. Whether recording physical objects, plants or the human body, within architecturally resonant spaces or outdoor resonant canyons, she creates incongruencies that reflect current realities. Her interconnected artistic practices include notated composition, alternative personas, and hybrid acoustic-electronic performance on Japanese traditional string instruments such as the koto and ichigenkin. Her work includes writing new Noh music, instrument building, wearable computing, and sonifying the behavior of plants, brain activity and insect movement and orchestra works. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including the Venice Biennale, MoMA PS1, Kunstmuseum Bonn, Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia. Masaoka is an Assistant Professor of Practice at Columbia and the Director of Sound Art MFA, and previously taught at the Milton Avery School of the Arts at Bard College. She is a Park Avenue Armory Studio Artist in 2019. She has a commission to create an outdoor sound installation for Sonic Innovations at the Caramoor in 2019. She has exhibited at the Contemporary Art Chicago, and the Laboratorium for Contemporary Art Museum at Ujazdowski Castle and Siggraph. She was the keynote speaker for NIME (New Interfaces for Musical Expression) in Brisbane, Australia and a Fulbright Fellow to Japan in 2016. She has been the recipient of such grants and commissions as the Doris Duke Artist Award, the Alpert Award in the Arts, The Gerbode Foundation, The Electronic Music Foundation, the MAP Fund, The NEA, The Montalvo Arts Center’s Lucas Artists Residency, STEIM, Issue Project Room (Siloh), The Headlands, and others. -

The Creative Application of Extended Techniques for Double Bass in Improvisation and Composition

The creative application of extended techniques for double bass in improvisation and composition Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Volume Number 1 of 2 Ashley John Long 2020 Contents List of musical examples iii List of tables and figures vi Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historical Precedents: Classical Virtuosi and the Viennese Bass 13 Chapter 2: Jazz Bass and the Development of Pizzicato i) Jazz 24 ii) Free improvisation 32 Chapter 3: Barry Guy i) Introduction 40 ii) Instrumental technique 45 iii) Musical choices 49 iv) Compositional technique 52 Chapter 4: Barry Guy: Bass Music i) Statements II – Introduction 58 ii) Statements II – Interpretation 60 iii) Statements II – A brief analysis 62 iv) Anna 81 v) Eos 96 Chapter 5: Bernard Rands: Memo I 105 i) Memo I/Statements II – Shared traits 110 ii) Shared techniques 112 iii) Shared notation of techniques 115 iv) Structure 116 v) Motivic similarities 118 vi) Wider concerns 122 i Chapter 6: Contextual Approaches to Performance and Composition within My Own Practice 130 Chapter 7: A Portfolio of Compositions: A Commentary 146 i) Ariel 147 ii) Courant 155 iii) Polynya 163 iv) Lento (i) 169 v) Lento (ii) 175 vi) Ontsindn 177 Conclusion 182 Bibliography 191 ii List of Examples Ex. 0.1 Polynya, Letter A, opening phrase 7 Ex. 1.1 Dragonetti, Twelve Waltzes No.1 (bb. 31–39) 19 Ex. 1.2 Bottesini, Concerto No.2 (bb. 1–8, 1st subject) 20 Ex.1.3 VerDi, Otello (Act 4 opening, double bass) 20 Ex.