Mahler Transcending London Symphony Orchestra Simon Rattle , Conductor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Symphony Orchestra with Sir Simon Rattle, Music Director

LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WITH SIR SIMON RATTLE, MUSIC DIRECTOR PROGRAM BARTÓK Concerto for Orchestra (1881 – 1945) Duke Bluebeard’s Castle VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5 (1887 – 1959) MAHLER Symphony No. 4 in G Major (1860 – 1911) PROGRAM NOTES Written by Dan Ruccia BÉLA BARTÓK CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA Times were rough for Béla Bartók in 1943. He and his wife, pianist Ditta Pázstory, had migrated to the United States in 1940 to escape the pro-Nazi regime in Hungary, but had found limited success as performers. To survive, Bartók did some ethnomusicological work at Columbia and occasionally lectured there and at and Harvard, but he was generally unsatisfied with his situation. To make matters worse, his health had recently deteriorated; in February 1943, he collapsed after a lecture at Harvard. When he was admitted to the hospital, he weighed only 87 pounds. It wasn’t clear how much longer he had to live. Initially, the nature of Bartók’s illness was unclear. Early diagnoses included tuberculosis and polycythemia. It was only in April 1944 that doctors pinned down his actual diagnosis—chronic myeloid leukemia—but by then, there was little that could be done. In May 1943, conductor Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony commissioned a new orchestral work from Bartók through the recently formed Koussevitzky Music Foundation. The ailing composer was initially hesitant; he did not want to take a commission that he might not be able to finish. But Koussevitzky insisted that the commission was a fait accompli and the money could only go to Bartók. With the commission in hand, it seems that Bartók became energized. -

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

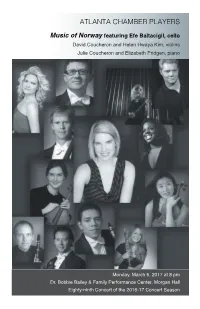

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

Bath Festival Orchestra Programme 2021

Bath Festival Orchestra photo credit: Nick Spratling Peter Manning Conductor Rowan Pierce Soprano Monday 17 May 7:30pm Bath Abbey Programme Carl Maria von Weber Overture: Der Freischütz Weber Der Freischütz (Op.77, The Marksman) is a German Overture to Der Freischütz opera in three acts which premiered in 1821 at the Schauspielhaus, Berlin. Many have suggested that it was the first important German Romantic opera, Strauss with the plot based around August Apel’s tale of the same name. Upon its premiere, the opera quickly 5 Orchestral Songs became an international success, with the work translated and rearranged by Hector Berlioz for a French audience. In creating Der Freischütz Weber Brentano Lieder Op.68 embodied the ideal of the Romantic artist, inspired Ich wollt ein Sträuẞlein binden by poetry, history, folklore and myths to create a national opera that would reflect the uniqueness of Säusle, liebe Myrthe German culture. Amor Weber is considered, alongside Beethoven, one of the true founders of the Romantic Movement in Morgen! Op.27 music. He lived a creative life and worked as both a pianist and music critic before making significant contributions to the operatic genre from his appointment at the Dresden Staatskapelle in 1817, Das Rosenband Op.36 where he realised that the opera-goers were hearing almost nothing other than Italian works. His three German operas acted as a remedy to this situation, Brahms with Weber hoping to embody the youthful Serenade No.1 in D, Op.11 Romantic movement of Germany on the operatic stage. These works not only established Weber as a long-lasting Romantic composer, but served to define German Romanticism and make its name as an important musical force in Europe throughout the 19th century. -

Roots & Origins

Sunday 16 December 2018 7–9.15pm Tuesday 18 December 2018 7.30–9.45pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT ROOTS & ORIGINS Brahms Violin Concerto Interval ROMANIAN Debussy Images Enescu Romanian Rhapsody No 1 Sir Simon Rattle conductor Leonidas Kavakos violin These performances of Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No 1 are generously RHAPSODY supported by the Romanian Cultural Institute 16 December generously supported by LSO Friends Welcome Latest News On Our Blog We are grateful to the Romanian Cultural BRITISH COMPOSER AWARDS MARIN ALSOP ON LEONARD Institute for their generous support of these BERNSTEIN’S CANDIDE concerts. Sunday’s concert is also supported Congratulations to LSO Soundhub Associate by LSO Friends, and we are delighted to have Liam Taylor-West and LSO Panufnik Composer Marin Alsop conducted Bernstein’s Candide, so many Friends with us in the audience. Cassie Kinoshi for their success in the 2018 with the LSO earlier this month. Having We extend our thanks for their loyal and British Composer Awards. Prizes were worked closely with the composer across important support of the LSO, and their awarded to Liam for his Community Project her career, Marin drew on her unique insight presence at all our concerts. The Umbrella and to Cassie for Afronaut, into Bernstein’s music, words and sense of a jazz composition for large ensemble. theatre to tell us about the production. I wish you a very happy Christmas, and hope you can join us again in the New Year. The • lso.co.uk/more/blog elcome to this evening’s LSO LSO’s 2018/19 concert season at the Barbican FELIX MILDENBERGER JOINS THE LSO concert at the Barbican. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Berliner Philharmoniker

Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director November 12–13, 2016 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert I Saturday, November 12, 8:00 pm 3 Concert II Sunday, November 13, 4:00 pm 15 Artists 31 Berliner Philharmoniker Concert I Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director Saturday Evening, November 12, 2016 at 8:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 14th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the Eugene and Emily Grant Family Foundation. This evening’s supporting sponsor is the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. This evening’s performance is funded in part by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Steinway piano used in this evening’s performance is made possible by William and Mary Palmer. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. Special thanks to Bill Lutes for speaking at this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Journeys International, sponsor of this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Aaron Dworkin, Melody Racine, Emily Avers, Paul Feeny, Jeffrey Lyman, Danielle Belen, Kenneth Kiesler, Nancy Ambrose King, Richard Aaron, and the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance for their support and participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. Deutsche Bank is proud to support the Berliner Philharmoniker. Please visit the Digital Concert Hall of the Berliner Philharmoniker at www.digitalconcerthall.com. -

Program Book

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

Mahler's Symphony No. 10

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS WEDNESDAY, MAY 17, 7:30PM [Concert] Gordon Gamm Theater at The Dairy Center • G. Kurtág: Signs, Games, Messages (Jelek, Játékok és Üzenetek) • D. Matthews: Romanza for Violin and Piano, op 119a (U.S. Premiere) • G. Mahler/A. Schnittke: Piano Quartet in a (fragments) • F. Schubert: String Quintet in C, D. 956, Op. posth. 163 THURSDAY, MAY 18, 1:30PM [Master Class] Boulder Public Library • The Conducting Fellows, Kenneth Woods, David Matthews and Mahler specialists. • Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen– Chamber version (Schoenberg) FRIDAY, MAY 19, 2:00PM [FILM] BOEDECKER THEATRE AT THE DAIRY CENTER, BOULDER • Ken Russell’s Mahler SATURDAY, MAY 20, [Symposium] (speaker order subject to change) • Morning Session – 8:30am – C-199 – Imig Building, CU Boulder • Frans Bouwman ”Transcribing Mahler 10: what does it show?” • David Matthews ”Mahler’s 10th Symphony – Restored to Life” • Kenneth Woods, Artistic Director and Conductor, Colorado MahlerFest “A Conductor’s Perspective on the Tenth Symphony” • Jerry Bruck assisted by Louise Bloomfield In“ Search of Mahler: A Personal Recollection” • Lunch – Atrium Lobby, ATLAS building, University of Colorado • Afternoon Session – 1:30pm - Rm 102 – ATLAS Building, CU Boulder • Panel Discussion with David Matthews, Kenneth Woods and Donald Fraser • Jason Starr’s “For the Love of Mahler – The Inspired Life of Henry-Louis de La Grange” Presented in Memory of Henry-Louis de La Grange SATURDAY, MAY 20, 7:30 PM [Orchestral Concert] Macky Auditorium, University of Colorado SUNDAY, MAY 21, 3:30 PM [Orchestral Concert] Macky Auditorium, University of Colorado • Sir Edward Elgar (arr. David Matthews): String Quartet in e, opus 83 – arranged for string orchestra (2010) (US Premiere) • Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. -

Wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt

BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Geflohen - verstummt - wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt GESPRÄCHSKONZERT DER REIHE MUSICA REANIMATA AM 22. NOVEMBER 2016 IN BERLIN BESTANDSVERZEICHNIS DER MEDIEN VON UND ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT IN DER ZENTRAL- UND LANDESBIBLIOTHEK BERLIN INHALTSANGABE KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Noten Seite 3 Aufnahmen auf CD Seite 4 Aufnahmen in der Naxos Music Library Seite 6 SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Seite 7 LEGENDE Freihand Bestand im Lesesaal frei zugänglich Magazin Bestand für Leser nicht frei zugänglich, Bestellung möglich Außenmagazin Bestand außerhalb der Häuser, Bestellung möglich AGB Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek, Blücherplatz 1, 10961 Berlin – Kreuzberg Berlin-Studien im Haus BStB (Berliner Stadtbibliothek) BStB Berliner Stadtbibliothek, Breite Str. 30-36, 10178 Berlin – Mitte Naxos Music Library Streamingportal mit klassischer Musik –- sowohl an den Datenbank-PCs der ZLB als auch (mit Bibliotheksausweis) von zu Hause nutzbar 2 KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT NOTEN Mediterranean songs : for tenor and orchestra = Gesänge vom Mittelmeer / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, c 1996. - 83 Seiten. HPS 1294 Exemplare: Standort Außenmagazin AGB Signatur 008/000 009 519 (No 139 Golds 1) Passacaglia opus 4 for large orchestra / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, 1998. - 1 Studienpartitur (22 Seiten). - ISMN M-060-10791-7 Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur 108/000 052 355 (No 147 Golds 1) String quartet no 2 : for string quartet [Noten] / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, [1991]. - 1 Partitur (42 Seiten) ; 31 cm. - Anmerkungen des Komponisten in Deutsch und Englisch Exemplare: Standort Freihand AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 2 String quartet no. 4 (1992) / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London [u.a.] : Boosey & Hawkes, 1994. - 20 Seiten Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 1 [Sinfonien, Nr. -

YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair

YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Biography, February 2013 Yannick Nézet-Séguin triumphantly opened his inaugural season as the eighth music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra in the fall of 2012. From the Orchestra’s home in Verizon Hall to the Carnegie Hall stage, Nézet-Séguin’s highly collaborative style, deeply-rooted musical curiosity, and boundless enthusiasm, paired with a fresh approach to orchestral programming, have been heralded by critics and audiences alike. The New York Times has called Yannick “phenomenal,” adding that under his baton, “the ensemble, famous for its glowing strings and homogenous richness, has never sounded better.” In his first official season in Philadelphia, Yannick has taken the Orchestra to new musical heights in concerts at home, and has further distinguished himself in the community, with a powerful performance at the Orchestra’s annual Martin Luther King Tribute Concert, working with young musicians from the School District of Philadelphia’s All City Orchestra, establishing a relationship with the Curtis Institute, and ringing in 2013 with his Philadelphia audience with a festive New Year’s Eve concert. Following on the heels of a February 2013 announcement of a recording project with Deutsche Grammophon, Yannick and the Orchestra will record Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring together. Over the past decade, Nézet-Séguin has established himself as a musical leader of the highest caliber and one of the most exciting talents of his generation. Since 2008 he has been music director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic and principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic, and since 2000 artistic director and principal conductor of Montreal’s Orchestre Métropolitain. -

A Conductor for the Ages Jonathan E.D

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2015 yS mposium Apr 1st, 1:20 PM - 1:40 PM A Conductor for the Ages Jonathan E.D. Royce Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Music Performance Commons Royce, Jonathan E.D., "A Conductor for the Ages" (2015). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 17. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2015/podium_presentations/17 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR FOR THE AGES [Document subtitle] JONATHAN ROYCE HLMU 3320: MUSIC HISTORY April 1, 2015 Royce 1 Music is an interesting idea. It is the epitome of ephemerality. Despite being audible one moment and then gone forever in another, its affects are long lasting. It must have a beginning and an end, but the aftermath can linger within the listener. Not only did Herbert von Karajan direct music in a way that encompassed that description, but he himself encompassed that description. Herbert von Karajan was an Austrian who conducted in Germany in the twentieth century. It can be said that he greatly impacted Germany in the area of musical performance as well as film and recording while he presided as conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, or Berliner Philharmoniker as it would be called in the native German tongue.