Scottish Business and Industrial History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SRING MIGRANTS 2020 (As at 5/5/20)

SRING MIGRANTS 2020 (as at 5/5/20). Please let us know of any spring migrants you see in Argyll even if the species had already been noted. We are keen to see the overall pattern of arrival. Contact Jim [email protected] Tel: 01546 603967 SPECIES DATE LOCATION OBSERVER Comment Common Quail Osprey 27/3/20 Holy Loch, Cowal Mark Utting Two, also singles 28-29th Osprey 31/3/20 Sorobaidh Bay, Tiree John Bowler Flew in off the sea Osprey 2/4/20 South Kintyre Neil Brown Caught a trout.. Osprey 3/4/20 Central Cowal Neil Hammatt One Corn Crake 9/4/20 Friesland, Coll Ben Jones Calling Corn Crake 9/4/20 Loch Gorm area Islay Per James How Calling Corn Crake 15/4/20 Balephuil, Tiree John Bowler Two males calling Corn Crake 16/4/20 Machir Bay, Islay Matt Jackson One calling Corn Crake 16/4/20 Portnahaven, Islay Mary Redman One calling Dotterel Whimbrel 10/4/20 Loch a’ Phuill, Tiree John Bowler One Whimbrel 10/4/20 Loch na Cille, Keills, Mid-Argyll John Aitchison One Whimbrel 16/4/20 Machrihanish SBO, Kintyre D Millward / Jo Goudie Seven>N Whimbrel 20/4/20 Holy Loch, Cowal Neil Hammatt One Black-tailed Godwit 22/3/20 Sandaig, Tiree John Bowler Five Common Sandpiper 5/4/20 Loch Feochan, Mid-Argyll John Speirs One Common Sandpiper 9/4/20 Add Estuary, Mid-Argyll David Jardine One+ Common Sandpiper 9/4/20 Loch Fyne, Mid-Argyll Alan Dykes One Common Sandpiper 10/4/20 Crinan Canal, Bellanoch, Mid-Argyll Jim Dickson Two Arctic Skua 18/4/20 Loch a’ Phuill, Tiree John Bowler Two Arctic Skua 22/4/20 Coll ? Two Sandwich Tern 6/4/20 Port Righ Bay, Kintyre Alasdair Paterson One Sandwich Tern 8/4/20 Kirn, Cowal Alistair McGregor Three Sandwich Tern 9/4/20 Machrihanish SBO, Kintyre D Millward /Jo Goudie Six Sandwich Tern 9/4/20 Dunaverty, Kintyre Brian Morton & family Five Sandwich Tern 10/4/20 Bruichladdich, Islay Peter Roberts One Sandwich Tern 10/4/20 Loch na Cille, Keills, Mid-Argyll John Aitchison One Sandwich Tern 11/4/20 Kyles, Cowal Arlyn Thursby Two Sandwich Tern 12/4/20 Loch a’ Phuill, Tiree John Bowler One Little Tern 7/4/20 Big Strand, Islay Duncan MacNeill At least one. -

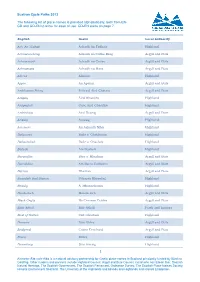

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

20 1022 Response

OFFICIAL Our Ref: IM-FOI-2020-1022 Date: 16 July 2020 FREEDOM OF INFORMATION (SCOTLAND) ACT 2002 I refer to your recent request for information which has been handled in accordance with the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002. For ease of reference, your request is replicated below together with the response. A three year time period for each area is provided for comparison purposes. Under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 please provide me with the following: 1. The relevant crime figures in respect of housebreaking on the Isle of Lewis; Table 1: Recorded housebreaking offences on Isle of Lewis 1,2 Calendar Years 2017 - 2020 (up to and including 31st May 2020) Crime bulletin crime type 2017 2018 2019 2020 Theft by housebreaking - domestic property - dwell 1 1 - - Theft by housebreaking - domestic property - non- - 1 1 2 dwell Theft by housebreaking - other property 3 2 1 1 Total 4 4 2 3 All statistics are provisional and should be treated as management information. All data have been extracted from Police Scotland internal systems and are correct as at 25/6/2020. 1. The data was extracted using the crime's raised date and by using SGJD codes 301904, 301905 and 3019046. 2. Specified areas have been selected by selecting the Area Command 'Western Isles' which covers Isle of Lewis. 2. The relevant crime figures in respect of housebreaking on the Cowal Peninsula, relative to two principal areas: Cairndow, Argyll and Clachaig, Argyll and Bute. A check of our systems provides there were no recorded housebreaking crimes in this period. -

Iron Making in Argyll

HISTORIC ARGYLL 2009 Iron smelting in Argyll, and the chemistry of the process by Julian Overnell, Kilmore. The history of local iron making, particularly the history of the Bonawe Furnace, is well described in the Historic Scotland publication of Tabraham (2008), and references therein. However, the chemistry of the processes used is not well described, and I hope to redress this here. The iron age started near the beginning of the first millennium BC, and by the end of the first millennium BC sufficient iron was being produced to equip thousands of troops in the Roman army with swords, spears, shovels etc. By then, local iron making was widely distributed around the globe; both local wood for making charcoal, and (in contrast to bronze making) local sources of ore were widely available. The most widely distributed ore was “bog iron ore”. This ore was, and still is, being produced in the following way: Vegetation in stagnant water starts to rot and soon uses up all the available oxygen, and so produces a water at the bottom with no oxygen (anaerobic) which also contains dissolved organic compounds. This solution is capable of slowly leaching iron from the soils beneath to produce a weak solution of dissolved iron (iron in the reduced, ferrous form). Under favourable conditions this solution percolates down until it meets some oxygen (or oxygenated water) at which point the iron precipitates (as the oxidized ferric form). This is bog iron ore and comprises a somewhat ill-defined brown compound called limonite (FeOOH.nH2O), often still associated with particles of sand etc. -

THE PLACE-NAMES of ARGYLL Other Works by H

/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE PLACE-NAMES OF ARGYLL Other Works by H. Cameron Gillies^ M.D. Published by David Nutt, 57-59 Long Acre, London The Elements of Gaelic Grammar Second Edition considerably Enlarged Cloth, 3s. 6d. SOME PRESS NOTICES " We heartily commend this book."—Glasgow Herald. " Far and the best Gaelic Grammar."— News. " away Highland Of far more value than its price."—Oban Times. "Well hased in a study of the historical development of the language."—Scotsman. "Dr. Gillies' work is e.\cellent." — Frce»ia7is " Joiifnal. A work of outstanding value." — Highland Times. " Cannot fail to be of great utility." —Northern Chronicle. "Tha an Dotair coir air cur nan Gaidheal fo chomain nihoir."—Mactalla, Cape Breton. The Interpretation of Disease Part L The Meaning of Pain. Price is. nett. „ IL The Lessons of Acute Disease. Price is. neU. „ IIL Rest. Price is. nef/. " His treatise abounds in common sense."—British Medical Journal. "There is evidence that the author is a man who has not only read good books but has the power of thinking for himself, and of expressing the result of thought and reading in clear, strong prose. His subject is an interesting one, and full of difficulties both to the man of science and the moralist."—National Observer. "The busy practitioner will find a good deal of thought for his quiet moments in this work."— y^e Hospital Gazette. "Treated in an extremely able manner."-— The Bookman. "The attempt of a clear and original mind to explain and profit by the lessons of disease."— The Hospital. -

COWAL Sustainable, Unsustainable and Historic Walks and Cycling in Cowal

SEDA Presents PENINSULA EXPEDITION: COWAL Sustainable, Unsustainable and Historic walks and cycling in Cowal S S R Road to Inverarary and Achadunan F * * Q G D Kayak through the * Crinnan Canal E P N B K A C Kayak to Helensburgh O * * * Z L Dunoon T Map J Train to Glasgow Central U X I H V M W Y To Clonaig / Lochranza Ferry sponsored by the Glasgow Institute Argyll Sea Kayak Trail of Architects 3 ferries cycle challenge Cycle routes around Dunoon 5 ferries cycle challenge Cycle routes NW Cowal Cowal Churches Together Energy Project and Faith in Cowal Many roads are steep and/or single * tracked, the most difcult are highlighted thus however others Argyll and Bute Forrest exist and care is required. SEDA Presents PENINSULA EXPEDITION: COWAL Sustainable, Unsustainable and Historic walks and cycling in Cowal Argyll Mausoleum - When Sir Duncan Campbell died the tradition of burying Campbell Clan chiefs and the Dukes of Argyll at Kilmun commenced, there are now a total of twenty Locations generations buried over a period of 500 years. The current mausoleum was originally built North Dunoon Cycle Northern Loop in the 1790s with its slate roof replaced with a large cast iron dome at a later date. The A - Benmore Botanic Gardens N - Glendaruel (Kilmodan) mausoleum was completely refur-bished in the late 1890s by the Marquis of Lorne or John B - Puck’s Glen O - Kilfinan Church George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll. Recently the C - Kilmun Mausoleum, Chapel, P - Otter Ferry mausoleum has again been refurbished incorporating a visitors centre where the general Arboreum and Sustainable Housing Q - Inver Cottage public can discover more about the mausoleums fascinating history. -

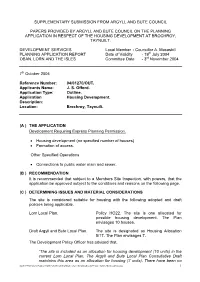

Supplementary Submission from Argyll and Bute Council

SUPPLEMENTARY SUBMISSION FROM ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL PAPERS PROVIDED BY ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL ON THE PLANNING APPLICATION IN RESPECT OF THE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT AT BROCHROY, TAYNUILT. DEVELOPMENT SERVICES Local Member - Councillor A. Macaskill PLANNING APPLICATION REPORT Date of Validity - 19th July 2004 OBAN, LORN AND THE ISLES Committee Date - 3rd November 2004 7th October 2004 Reference Number: 04/01270/OUT. Applicants Name: J. S. Offord. Application Type: Outline. Application Housing Development. Description: Location: Brochroy, Taynuilt. (A ) THE APPLICATION Development Requiring Express Planning Permission. • Housing development (no specified number of houses) • Formation of access. Other Specified Operations • Connections to public water main and sewer. (B ) RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that subject to a Members Site Inspection, with powers, that the application be approved subject to the conditions and reasons on the following page. (C ) DETERMINING ISSUES AND MATERIAL CONSIDERATIONS The site is considered suitable for housing with the following adopted and draft policies being applicable. Lorn Local Plan. Policy HO22. The site is one allocated for possible housing development. The Plan envisages 10 houses. Draft Argyll and Bute Local Plan. The site is designated as Housing Allocation 5/17. The Plan envisages 7. The Development Policy Officer has advised that, “The site is included as an allocation for housing development (10 units) in the current Lorn Local Plan. The Argyll and Bute Local Plan Consultative Draft maintains this area as an allocation for housing (7 units). There have been no \\EDN-APP-001\USERS\PUBLIC\!WORK PENDING\ENVIRONMENT CROFTING EVIDENCE\SUPP SUB FROM A AND B COUNCIL.DOC 1 timeous objections received in relation to this area as part of the Argyll and Bute Local Plan consultation process. -

Proposal for the Closure of X School

Argyll and Bute Council Customer Services: Education PROPOSAL DOCUMENT: MARCH 2019 Review of Education Provision Ardchattan Primary School Argyll and Bute Council Proposal for the closure of Ardchattan Primary School SUMMARY PROPOSAL It is proposed that education provision at Ardchattan Primary School be discontinued with effect from 21st October 2019. Pupils of Ardchattan Primary School will continue to be educated at Lochnell Primary School. The catchment area of Lochnell Primary School shall be extended to include the current catchment area of Ardchattan Primary School. Reasons for this proposal This is the best option to address the reasons for the proposals which are; Ardchattan Primary School has been mothballed for four years. The school roll is very low and not predicted to rise in the near future. The annual cost of the mothballing of the building is £2,147 Along with several other rural Councils, Argyll and Bute is facing increasing challenges in recruiting staff. At the time of writing there are 14 vacancies for teachers and 2 vacancies for head teachers in Argyll and Bute. Whilst the school is mothballed, the building is deteriorating with limited budges for maintenance. This document has been issued by Argyll and Bute Council in regard to a proposal in terms of the Schools (Consultation) (Scotland) Act 2010 as amended. This document has been prepared by the Council’s Education Service with input from other Council Services. DISTRIBUTION A copy of this document is available on the Argyll and Bute Council website: https://www.argyll-bute.gov.uk/education-and-learning -

Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week Ending 30 May2014

Weekly Planning list for 30 May2014 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 30 May2014 30/5/2014 10:54 Weekly Planning list for 30 May2014 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 14/00927/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Cowal Community Council: Kilmun Community Council Proposal: Erection of a dwellinghouse,installation of septic tank and for- mation of vehicular access Location: Plot 1, Land East Of Powdemill House,Clachaig, Dunoon, Argyll And Bute,PA23 8RE Applicant: Aitchesse Ltd Suite G, River viewHouse , Friar ton Road, Per th, PH2 8DF Ag ent: Richard RobbArchitects 75-77 AlbertRoad, Gourock, PA19 1NJ Development Type: 03B - Housing - Local Grid Ref: 212486 - 681566 Reference: 14/00934/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Cowal Community Council: Kilmun Community Council Proposal: Erection of dwellinghouse,installation of septic tank and for ma- tion of vehicular access Location: Plot 2, Land East Of Powdemill House,Clachaig, Dunoon, Argyll Applicant: Aitchesse Ltd Suite G, River viewHouse , Friar ton Road, Per th, PH2 8DF Ag ent: Richard RobbArchitects 75-77 AlbertRoad, Gourock, PA19 1NJ Development Type: 03B - Housing - Local Grid Ref: 102000 - 604000 Reference: 14/00935/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Cowal Community Council: Kilmun Community Council Proposal: Erection of dwellinghouse,installation of septic tank and for ma- tion of vehicular access Location: -

Appendix - Representations Received For: 18/01125/PP

Appendix - Representations Received for: 18/01125/PP Total 282 Representations - Summary Totals 1 - OBJECTORS 274 2 - SUPPORTERS 6 3 - NEUTRAL 2 1 - OBJECTORS Tom 21/06/2018 O Abel Smith, David Old Rectory Quenington Old Rectory 17/08/2018 O Glox GL7 5BN Abel Smith, Lucy Quenington Old Rectory Quenington 20/08/2018 O Cirencester Glos GL7 5 BN Adams, Robert Clattercote House Claydon Oxon OX17 20/06/2018 O 1ES Adamson-Eadie, Ann 3 Bowhouse Head Girdle Toll Irvine 17/08/2018 O Ayrshire KA11 1NU Allfrey, Peter Dolphin Lodge Rowdenfield Devizes 22/06/2018 O Wiltshire SN10 2JD Andre, Pierre 99 Uxbridge Road Hampton Hill 25/06/2018 O Middlesex TW12 1SL Asquith, Stephen 29 Waters Edge Close Whitehaven 22/06/2018 O Cumbria CA28 9PE Barr, Anne 3 Mull Terrace Soroba Oban PA34 4YB 22/06/2018 O Barry, Hazel The Kestrel Bonawe Oban Argyll And 26/06/2018 O Bute PA37 1RL Bartle, Roy 17 Peterborough Avenue Leicester 22/06/2018 O LE15 6EB Baxter, Murdoch S Amfield Clachan Seil By Oban PA34 4TL 22/06/2018 O Beggs, Rab 17 Baberton Mains Wood Edinburgh 22/06/2018 O EH14 3DU Bennett, Fred Caretaker's Flat Achnacloich House 26/06/2018 O Achnacloich Oban Argyll And Bute PA37 1PR Bettison, Cherie 52 Glen Gardens Callander Perthshire 22/06/2018 O FK17 8ES Bloor, Monica Swn Y Mor North Connel Oban Argyll 22/06/2018 O And Bute PA37 1QZ Bloor, Nigel Swn Y Mor North Connel Oban Argyll 22/06/2018 O And Bute PA37 1QZ Bloor, Russell Overton 2 Whitelands Road Baildon 22/06/2018 O West Yorkshire BD17 6NL Bonniwell, Tom 2 Dalnabeich North Connel Oban Argyll 26/06/2018 O -

478 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

478 bus time schedule & line map 478 Dunoon - Portavadie View In Website Mode The 478 bus line (Dunoon - Portavadie) has 9 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Auchenbreck: 3:35 PM (2) Clachan Of Glendaruel: 2:50 PM (3) Colintraive: 7:12 AM - 5:37 PM (4) Colintraive: 9:35 AM - 3:40 PM (5) Dunans: 3:35 PM (6) Dunoon: 7:48 AM - 7:30 PM (7) Kyles View: 7:00 AM (8) Kyles View: 7:27 AM - 4:28 PM (9) Portavadie: 5:50 AM - 6:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 478 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 478 bus arriving. Direction: Auchenbreck 478 bus Time Schedule 8 stops Auchenbreck Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:35 PM Kilmodan Primary School, Clachan Of Glendaruel Tuesday 3:35 PM Woodlands Cottage, Duiletter Wednesday 3:35 PM Torach, Ormidale Thursday 3:35 PM Primary School, Caol Ruadh Friday 3:35 PM Ferry Terminal, Colintraive Saturday Not Operational Road End, Kyles View Ferry Terminal, Colintraive 478 bus Info A886 Direction: Auchenbreck Turning Area, Auchenbreck Stops: 8 Trip Duration: 52 min Line Summary: Kilmodan Primary School, Clachan Of Glendaruel, Woodlands Cottage, Duiletter, Torach, Ormidale, Primary School, Caol Ruadh, Ferry Terminal, Colintraive, Road End, Kyles View, Ferry Terminal, Colintraive, Turning Area, Auchenbreck Direction: Clachan Of Glendaruel 478 bus Time Schedule 7 stops Clachan Of Glendaruel Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:50 PM Ferry Terminal, Portavadie Tuesday 2:50 PM Crossroads, Millhouse Wednesday -

1 DEVELOPMENT SERVICES Local Member

DEVELOPMENT SERVICES Local Member - Councillor B. Marshall PLANNING APPLICATION REPORT Date of Validity - 25th October 2005 Bute and Cowal Area Committee Date - 10th January 2006 8th December 2005 Reference Number: 05/01917/DET Applicants Name: Brian & Lisa Ledsom Application Type: Detailed Application Description: Retention of timber decking and fence Location: 1 Bonnieblink Cottage, Clachaig Glen Lean (A ) THE APPLICATION Development Requiring Express Planning Permission. • Retention of timber decks • Retention of timber boundary treatments (B ) RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that planning permission be Refused for the reason set out on the following page. (C ) DETERMINING ISSUES AND MATERIAL CONSIDERATIONS This application seeks the retention of two timber decks and a timber fence. The application site is contained within Clachaig Conservation Village. The retention of the two decking areas is considered to be acceptable given the minimal impact that they have upon the character and setting of Bonnieblink Cottage and Clachaig Conservation Village. The timber fence that encloses the rear garden presents an alien form of development that detracts from the setting of Bonnieblink Cottage and contravenes the provisions of policy POL BE 12 ‘Clachaig Conservation Village’. The fence as constructed is unacceptable. Two letters of objection to the fence have been received. Whilst the retention of the timber decks is considered to be acceptable the application cannot be determined in part and on the basis that the timber fence has an adverse visual impact on the conservation area, a refusal of planning permission is appropriate. Angus J Gilmour Head of Planning Services Case Officer: J. Irving 01369-70-8621 Area Team Leader D.