The Poetics of Fragmentation in Contemporary British and American Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holly Sykes's Life, the 'Invisible' War, and the History Of

LITERATURE Journal of 21st-century Writings Article How to Cite: Parker, J.A., 2018. “Mind the Gap(s): Holly Sykes’s Life, the ‘Invisible’ War, and the History of the Future in The Bone Clocks.” C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, 6(3): 4, pp. 1–21. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/c21.47 Published: 01 October 2018 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, which is a journal of the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-profit publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Parker, J.A., 2018. “Mind the Gap(s): Holly Sykes’s Life, the ‘Invisible’ War, and the History of the Future in The Bone LITERATURE Journal of 21st-century Writings Clocks.” C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, 6(3): 2, pp. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/c21.47 ARTICLE Mind the Gap(s): Holly Sykes’s Life, the ‘Invisible’ War, and the History of the Future in The Bone Clocks Jo Alyson Parker Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia, PA, US [email protected] David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks (2014) features a complex temporal scheme. -

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

The Limitless Self: Desire and Transgression in Jeanette Winterson’S Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit and Written on the Body

The Limitless Self: Desire and Transgression in Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit and Written on the Body TREBALL DE RECERCA Francesca Castaño Méndez MÀSTER: Construcció I Representació d’Identitats Culturals. ESPECIALITAT: Estudis de parla anglesa. TUTORIA: Gemma López i Ana Moya TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARIES: “Only by imagining what we might be can we become more than we are”……………………………..............................1 CHAPTER 1: “God owns heaven but He craves the earth: The Quest for the Self in Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit”……..…9 1.1: “Like most people I lived for a long time with my mother and father”……….…11 1.2: “Why do you want me to go? I asked the night before”…………………….…...18 1.3: “The heathen were a daily household preoccupation”……………………….…..21 1.4: “It was spring, the ground still had traces of snow, and I was about to be married”……………………………...................................................................23 1.5: “Time is a great deadener. People forget, get bored, grow old, go away”….……26 1.6: “That walls should fall is the consequence of blowing your own trumpet”……..27 1.7: “It all seemed to hinge around the fact that I loved the wrong sort of people”……………………………...................................................................30 1.8: “It is not possible to change anything until you understand the substance you wish to change”……………………………......................................................32 CHAPTER 2: “It’s the clichés that cause the trouble: Love and loss in Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body”…………………………….....36 2.1: “Why is the measure of love loss?”…………………………...............................40 2.2: “Written on the body is a secret code only visible in certain lights: the accumulations of a lifetime gather there”..…………………………................50 2.3: “Love is worth it”……………………………......................................................53 CONCLUSIONS: “I’m telling you stories. -

In the Mix: the Potential Convergence of Literature and New Media in Jonathan Lethem’S ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’

In the Mix: The Potential Convergence of Literature and New Media in Jonathan Lethem’s ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’ Zara Dinnen Journal of Narrative Theory, Volume 42, Number 2, Summer 2012, pp. 212-230 (Article) Published by Eastern Michigan University DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jnt.2012.0009 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/488160 Access provided by University of Birmingham (8 Jan 2017 15:33 GMT) In the Mix: The Potential Convergence of Literature and New Media in Jonathan Lethem’s ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’ Zara Dinnen This article considers the reinscription of certain ideas of authorship in a digital age, when literary texts are produced through a medium that sub- stantiates and elevates composite forms and procedures over distinct orig- inal versions. Digital media technologies reconfigure the way in which we apply such techniques as collage, quotation, and plagiarism, comprising as they do procedural code that is itself a mix, a mash-up, a version of a ver- sion of a version. In the contemporary moment, the predominance of a medium that effaces its own means of production (behind interfaces, ‘pages,’ or ‘sticky notes’) suggests that we may no longer fetishize the master-copy, or the originary script, and that we once again need to re- theorize the term ‘author,’ asking for example how we can instantiate such a notion through a medium that abstracts the indelible and rewrites it as in- finitely reproducible and malleable.1 If the majority of texts written today—be they literary, academic, or journalistic—are first produced on a computer, it is increasingly necessary to think about how the ‘author’ in that instance may be not a rigid point of origin, but instead a relay for al- ternative modes of production, particularly composite modes of produc- tion, assuming such positions as ‘scripter,’ ‘producer,’ or even ‘DJ.’ By embarking on this path of enquiry, this article attempts to produce a JNT: Journal of Narrative Theory 42.2 (Summer 2012): 212–230. -

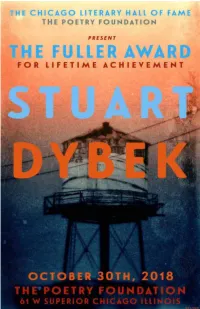

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Lincoln in the Bardo

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Lincoln in the Bardo INTRODUCTION RELATED LITERARY WORKS Lincoln in the Bardo borrows the term “Bardo” from The Bardo BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGE SAUNDERS Thodol, a Tibetan text more widely known as The Tibetan Book of . Tibetan Buddhists use the word “Bardo” to refer to George Saunders was born in 1958 in Amarillo, Texas, but he the Dead grew up in Chicago. When he was eighteen, he attended the any transitional period, including life itself, since life is simply a Colorado School of Mines, where he graduated with a transitional state that takes place after a person’s birth and geophysical engineering degree in 1981. Upon graduation, he before their death. Written in the fourteenth century, The worked as a field geophysicist in the oil-fields of Sumatra, an Bardo Thodol is supposed to guide souls through the bardo that island in Southeast Asia. Perhaps because the closest town was exists between death and either reincarnation or the only accessible by helicopter, Saunders started reading attainment of nirvana. In addition, Lincoln in the Bardo voraciously while working in the oil-fields. A eary and a half sometimes resembles Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, since later, he got sick after swimming in a feces-contaminated river, Saunders’s deceased characters deliver long monologues so he returned to the United States. During this time, he reminiscent of the self-interested speeches uttered by worked a number of hourly jobs before attending Syracuse condemned sinners in The Inferno. Taken together, these two University, where he earned his Master’s in Creative Writing. -

Claude Simon: the Artist As Orion

Claude Simon: The Artist as Orion 1blind Orion hungry for the morn1 S.W. Sykes Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow 1973 ProQuest Number: 11017972 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11017972 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks are due to Dr Stanley Jones, of the French Department in the University of Glasgow, for the interest shown and advice given during the supervision of this thesis; to the Staff of Glasgow University Library; and to / A M. Jerome Lindon, who allowed me to study material kept in the offices of Editions de Minuit. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I Prolegomena to Le Vent Early Writings 19^5-5^ CHAPTER II Chaos and the Semblance of Order Le Vent 1957 CHAPTER III The Presence of the Past: L 'Herbe 1958 CHAPTER IV The Assassination of Time: La Route des Flandres i960 CHAPTER V A Dream of Revolution:. Le Palace 1962 CHAPTER VI •A pattern of timeless moments': Histoire 1967 -

Centre for New Writing, Bring the Best Known Contemporary Writers Directly with HOME to Manchester to Discuss and Read from Their Work

Venue HOME Time & Date 7pm, Monday 13 March 2017 Price LITERATURE LIVE: SPRING 2017 Centre £10 / £8 These unique literature events, organised by the University’s Tickets are available Centre for New Writing, bring the best known contemporary writers directly with HOME to Manchester to discuss and read from their work. Everyone is for New 0161 200 1500 welcome, and tickets include discounts at the Blackwell bookstall and a complimentary drink at our Literature Live wine receptions. Writing © Mimsy Moller © Mimsy Neil Jordan Jeanette Winterson “In Conversation” with Neil Jordan Neil Jordan was born in 1950 in Sligo. His first book of stories, Night in Tunisia, won the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1979, and his subsequent critically acclaimed novels include The Past, Sunrise with Sea Monster, Shade and, most recently, The Drowned Detective. The films he has written and directed have won multiple awards, including an Academy Award Centre for New Writing (The Crying Game), a Golden Bear at Venice School of Arts, Languages and Cultures (Michael Collins), a Silver Bear at Berlin (The The University of Manchester Butcher Boy) and several BAFTAS (Mona Lisa and Oxford Road © Jillian Edelstein The End of the Affair). Manchester M13 9PL Jordan’s latest novel Carnivalesque is a Box Office: 0161 275 8951 bewitching, modern fairytale exploring identity Email: [email protected] and the loss of innocence and is published in © Sam Churchill February 2017. Jeanette Winterson Online tickets: www.quaytickets.com Jordan will be in conversation with Jeanette -

New Directions in Popular Fiction

NEW DIRECTIONS IN POPULAR FICTION Genre, Distribution, Reproduction Edited by KEN GELDER New Directions in Popular Fiction Ken Gelder Editor New Directions in Popular Fiction Genre, Distribution, Reproduction Editor Ken Gelder University of Melbourne Parkville , Australia ISBN 978-1-137-52345-7 ISBN 978-1-137-52346-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-52346-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956660 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

After Fiction? Democratic Imagination in an Age of Facts

After Fiction? Democratic Imagination in an Age of Facts §1 Philosophical reflection on the relationship between democracy and literature tends to take the novel as its privileged object of analysis, albeit for different reasons in the Francophone and Anglophone contexts. For Jacques Rancière, the genre (or rather non-genre) of the novel exemplifies the democratic disturbance that is the very principle of literature: “La maladie démocratique et la performance littéraire ont même principe: cette vie de la lettre muette-bavarde, de la lettre démocratique qui perturbe tout rapport ordonné entre l’ordre du discours et l’ordre des états”1. In contrast to this model of disruption to the existing order of representations, Anglophone philosophers often locate the democratic dimension of the novel in its promotion of shared understanding, a kind of training in liberal solidarity through imaginative identification. §2 My aim here is not to detail the similarities and differences between these approaches, but rather to confront these views with the current instability of the link between the genre of the novel and democratic community. The literary field in the 21st century is increasingly troubled by a new kind of democratic disorder. With the proliferation of information and narrative forms, factual modes of writing increasingly become the privileged site of literature’s engagement with the real. This “factual turn”, which in the Anglophone world has led to large claims for the powers of literary nonfiction, is also visible, although differently articulated, in contemporary French literature. We may wonder whether this development signals a renewed involvement of literature in public discourse, or a failure of the imaginative capacity to transform the actual. -

What Does It Mean to Write Fiction? What Does Fiction Refer To?

What Does It Mean to Write Fiction? What Does Fiction Refer to? Timothy Bewes Abstract Through an engagement with recent American fiction, this article explores the possibility that the creative procedures and narrative modes of literary works might directly inform our critical procedures also. Although this is not detailed in the piece, one of the motivations behind this project is the idea that such pro- cedures may act as a technology to enable critics to escape the place of the “com- mentator” that Michel Foucault anathematizes in his reflections on critical dis- course (for example, in his 1970 lecture “The Order of Discourse”). The article not only theorizes but attempts to enact these possibilities by inhabiting a subjective register located between fiction and criticism—a space that, in different ways, is also inhabited by the two literary works under discussion, Renee Gladman’s To After That and Colson Whitehead’s novel Zone One. (Gladman’s work also provides the quotations that subtitle each half of the essay.) Readers may notice a subtle but important shift of subjective positionality that takes place between sections I and II. 1 “What Does It Mean to Write Fiction? What Does Fiction Refer to?” These two questions are not mine—which means that they are not yours, either. They are taken from a work of fiction entitled To After That by the American writer Renee Gladman. I hesitate to call them a quotation, for, although they appear in Gladman’s book, the questions do not exactly belong to her narrator; or rather, they do not belong to the moment of Gladman’s narration. -

The Bone Clocks, Climate Change, and Human Attention

humanities Article Seeing What’s Right in Front of Us: The Bone Clocks, Climate Change, and Human Attention Elizabeth Callaway Environmental Humanities Program, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 November 2017; Accepted: 18 January 2018; Published: 26 January 2018 Abstract: The scales on which climate change acts make it notoriously difficult to represent in artistic and cultural works. By modeling the encounter with climate as one characterized by distraction, David Mitchell’s novel The Bone Clocks proposes that the difficulty in portraying climate change arises not from displaced effects and protracted timescales but a failure of attention. The book both describes and enacts the way more traditionally dramatic stories distract from climate connections right in front of our eyes, revealing, in the end, that the real story was climate all along. Keywords: climate change; clifi; digital humanities; literature and the environment Climate change is notoriously difficult to render in artistic and literary works. In the environmental humanities, there is an entire critical conversation around how and whether climate change can be represented in current cultural forms. The challenges often enumerated include the large time scales on which climate operates (Nixon 2011, p. 3), the displacement of climate effects (p. 2) literary plausibility of including extreme events in fiction (Ghosh 2016, p. 9), and the abstract nature of both the concept of climate (Taylor 2013, p. 1) and the idea of collective human action on the planetary scale (Chakrabarty 2009, p. 214). In this article, I argue that David Mitchell’s novel The Bone Clocks proposes a different primary difficulty in representing climate change.