CRIMINALIZING YOUTH POLITICS1 Abstract: the Present Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporting, and General Mentions Seem to Be in Decline

CYBER THREAT ANALYSIS Return to Normalcy: False Flags and the Decline of International Hacktivism By Insikt Group® CTA-2019-0821 CYBER THREAT ANALYSIS Groups with the trappings of hacktivism have recently dumped Russian and Iranian state security organization records online, although neither have proclaimed themselves to be hacktivists. In addition, hacktivism has taken a back seat in news reporting, and general mentions seem to be in decline. Insikt Group utilized the Recorded FutureⓇ Platform and reports of historical hacktivism events to analyze the shifting targets and players in the hacktivism space. The target audience of this research includes security practitioners whose enterprises may be targets for hacktivism. Executive Summary Hacktivism often brings to mind a loose collective of individuals globally that band together to achieve a common goal. However, Insikt Group research demonstrates that this is a misleading assumption; the hacktivist landscape has consistently included actors reacting to regional events, and has also involved states operating under the guise of hacktivism to achieve geopolitical goals. In the last 10 years, the number of large-scale, international hacking operations most commonly associated with hacktivism has risen astronomically, only to fall off just as dramatically after 2015 and 2016. This constitutes a return to normalcy, in which hacktivist groups are usually small sets of regional actors targeting specific organizations to protest regional events, or nation-state groups operating under the guise of hacktivism. Attack vectors used by hacktivist groups have remained largely consistent from 2010 to 2019, and tooling has assisted actors to conduct larger-scale attacks. However, company defenses have also become significantly better in the last decade, which has likely contributed to the decline in successful hacktivist operations. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Democracy Denied, Youth Participation and Criminalizing Digital Dissent

Journal of Youth Studies ISSN: 1367-6261 (Print) 1469-9680 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjys20 Democracy denied, youth participation and criminalizing digital dissent Judith Bessant To cite this article: Judith Bessant (2016) Democracy denied, youth participation and criminalizing digital dissent, Journal of Youth Studies, 19:7, 921-937, DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1123235 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1123235 Published online: 13 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 206 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjys20 Download by: [University of Liverpool] Date: 12 October 2016, At: 02:53 JOURNAL OF YOUTH STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 19, NO. 7, 921–937 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1123235 Democracy denied, youth participation and criminalizing digital dissent Judith Bessant School of Global, Urban & Social Studies, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Attention is given in this article to recent action by many liberal Received 1 May 2015 states to regulate and criminalize certain forms of political dissent Accepted 18 November 2015 reliant on new media. I ask how those working in the fields of KEYWORDS youth studies and social science more generally might understand Citizenship; media; politics; such processes of criminalizing political dissent involving young crime people digital media. I do this mindful of the prevailing concern about a ‘crisis in democracy’ said to be evident in the withdrawal by many young people from traditional forms of political engagement, and the need to encourage greater youth participation in democratic practices. -

Cyber News for Counterintelligence / Information Technology / Security Professionals 18 June 2014

Cyber News for Counterintelligence / Information Technology / Security Professionals 18 June 2014 Purpose June 17, Softpedia – (International) Evernote’s forum server has been hacked. Educate recipients of cyber events to aid in protecting Evernote advised certain users to change their passwords for the company’s forum electronically stored DoD, after attackers were able to access the forum server, potentially exposing hashed corporate proprietary, and/or Personally Identifiable passwords as well as email addresses and birthdays if users provided them. Those Information from theft, affected are users with forum accounts created in 2011 or earlier. Source: compromise, espionage http://news.softpedia.com/news/Evernote-s-Forum-Server-Has-Been-Hacked- Source 447035.shtml This publication incorporates open source news articles educate readers on security June 16, SC Magazine – (International) Technology sites “riskier” than illegal sites matters in compliance with in 2013, according to Symantec data. Symantec researchers released a post based USC Title 17, section 107, on Norton Web Safe user data that found that technology Web sites were the Para a. All articles are truncated to avoid the riskiest category of site to visit in 2013 based on the amount of malware and fake appearance of copyright antivirus attempts utilizing that category of sites to attempt to infect users. infringement Source: http://www.scmagazine.com/technology-sites-riskier-than-illegal-sites-in- Publisher 2013-according-to-symantec-data/article/355982/ * SA Jeanette Greene Albuquerque FBI June 16, Softpedia – (International) Internet Explorer script engine susceptible to Editor * CI SA Scott Daughtry attacks. A researcher with Fortinet reported that the script engine in Microsoft DTRA Counterintelligence Internet Explorer is potentially vulnerable to attacks via changing a security flag in Subscription Jscript or VBScript. -

Breach Report 2012.Pdf

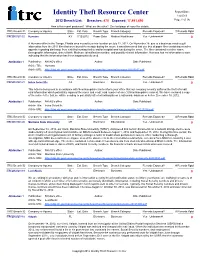

Identity Theft Resource Center Report Date: 1/4/2013 2012 Breach List: Breaches: 470 Exposed: 17,491,690 Page 1 of 95 How is this report produced? What are the rules? See last page of report for details. ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency State Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Records Exposed? # Records Rptd ITRC20121231-22 Humana KY 7/12/2012 Paper Data Medical/Healthcare Yes - Unknown # 0 A Humana office in the Tampa, Florida area moved to a new location on July 12, 2012. On November 28, due to a business need to pull information from the 2011 files that were boxed for storage during the move, it was discovered that one box of paper files containing member appeals regarding discharge from a skilled nursing facility and/or hospital was lost during the move. The files contained member name, demographic information, date of birth, Medicare identification number, and possibly clinical information. Humana has no information to date indicating that the information has been inappropriately used. Attribution 1 Publication: NH AG's office Author: Date Published: Article Title: Humana Article URL: http://doj.nh.gov/consumer/security-breaches/documents/humana-20121217.pdf ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency State Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Records Exposed? # Records Rptd ITRC20121231-21 Irvine Scientific CA Electronic Business Yes - Unknown # 0 This letter is being sent in accordance with New Hampshire law to inform your office that our company recently suffered the theft of credit card information which potentially exposed the name and credit card number of one (1) New Hampshire resident. -

FBI Arrests Alleged Nullcrew Hacktivist | Zdnet

5/9/2020 FBI arrests alleged NullCrew hacktivist | ZDNet MENU ● US MUST READ: Resetting the 5G goalposts: How the US declares victory FBI arrests alleged NullCrew hacktivist The FBI has arrested an alleged member of the NullCrew hacktivist group following cyberattacks on businesses and universities. By Charlie Osborne for Zero Day | June 19, 2014 -- 09:47 GMT (02:47 PDT) | Topic: Security The US Department of Justice has charged a man who allegedly participated in high-profile cyberattacks against corporations, universities and government agencies. In a statement released Wednesday (http://www.justice.gov/usao/iln/pr/chicago/2014/pr0616_01.html), the DoJ said Timothy French, 20, was arrested in Tennessee last week and is being charged with "federal computer hacking for allegedly conspiring to launch cyber attacks on two universities and three companies" as part of the hacktivist collective called NullCrew. Through these attacks, thousands of account names and passwords were stolen and published online. While the DoJ has not released the names of the companies, universities and governmental bodies that were targeted, the agency said that in one case, a successful cyberattack launched by NullCrew resulted in over 3,000 usernames, email addresses and passwords belonging to a foreign government’s ministry of defense to be released on the web. According to NullCrew's claims in 2012, the United Kingdom was the target. The law enforcement agency says social media sites and Skype are frequent tools used by NullCrew to select targets, organize cyberattacks and declare successful campaigns. Twitter, https://www.zdnet.com/article/fbi-arrests-alleged-nullcrew-hacktivist/ 1/4 5/9/2020 FBI arrests alleged NullCrew hacktivist | ZDNet for example, is often used to link to PasteBin files containing data dumps — information acquired after breaching a target's security. -

The Most Dangerous Cyber Nightmares in Recent Years Halloween Is the Time of Year for Dressing Up, Watching Scary Movies, and Telling Hair-Raising Tales

The most dangerous cyber nightmares in recent years Halloween is the time of year for dressing up, watching scary movies, and telling hair-raising tales. Events in recent years have kept companies on high alert. Every day we are seeing an increase in cyberattacks carried out by organized hacker organizations. In a matter of seconds, these threats can destabilize large corporations, stealing large quantities of money and personal data, as well shake the very foundations of entire world powers. Have a look at some of the most terrifying attacks of recent years. 2010 2011 2012 Operation Aurora RSA SecurID Stratfor A series of cyberattacks carried out RSA suffered a security breach as a Publication and dissemination of worldwide, targeting 34 companies, result of a cyberattack that sought internal emails exchanged between including Google. The attack was details about its SecureID system. personnel of the private intelligence perpetrated by a group of Chinese espionage agency Stratfor, as well as hackers. PlayStation Network emails exchanged with clients of the firm. 77 million accounts were Australian Government compromised and blocked PS3 and DDoS attacks, carried out by the PlayStation Portable users from Linkedin online community Anonymous, accessing the service for 23 hours. The passwords of nearly 6.5 million against the Australian Government. user accounts were stolen by Russian cybercriminals. Operation Payback An attack coordinated jointly against opponents of Internet piracy. 2013 2014 Cyberattack in South Korea Celebrity photos Cyber networks of major South 500 private photographs of several Korean banks and television celebrities, mostly women, were networks were shut down in an placed on 4chan and subsequently alleged act of cyber warfare. -

Regional Cyber Security: Moving Towards a Resilient ASEAN Cyber Security Regime

The RSIS Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. If you have any comments, please send them to the following email address: [email protected] Unsubscribing If you no longer want to receive RSIS Working Papers, please click on “Unsubscribe.” to be removed from the list. No. 263 Regional Cyber Security: Moving Towards a Resilient ASEAN Cyber Security Regime Caitríona H. Heinl S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 09 September 2013 About RSIS The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. Known earlier as the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies when it was established in July 1996, RSIS’ mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. To accomplish this mission, it will: Provide a rigorous professional graduate education with a strong practical emphasis, Conduct policy-relevant research in defence, national security, international relations, strategic studies and diplomacy, Foster a global network of like-minded professional schools. GRADUATE EDUCATION IN INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS RSIS offers a challenging graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The Master of Science (M.Sc.) degree programmes in Strategic Studies, International Relations and International Political Economy are distinguished by their focus on the Asia Pacific, the professional practice of international affairs, and the cultivation of academic depth. -

Prototipo De Detección De Divulgación De Información Privada Publicada En Internet Usando Como Fuente Red Social Twitter

PROTOTIPO DE DETECCIÓN DE DIVULGACIÓN DE INFORMACIÓN PRIVADA PUBLICADA EN INTERNET USANDO COMO FUENTE RED SOCIAL TWITTER CRISTIAN ANDRES CASTAÑEDA LOPEZ RODRIGO HERNANDEZ PEDRAZA UNIVERSIDAD PILOTO DE COLOMBIA FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍAS, INGENIERÍA DE SISTEMAS POSTGRADOS SANTA FE DE BOGOTÁ 2014 PROTOTIPO DE DETECCIÓN DE DIVULGACIÓN DE INFORMACIÓN PRIVADA PUBLICADA EN INTERNET USANDO COMO FUENTE RED SOCIAL TWITTER CRISTIAN ANDRES CASTAÑEDA LOPEZ RODRIGO HERNANDEZ PEDRAZA Trabajo de grado presentado como opción de grado al título de ESPECIALISTA DE SEGURIDAD INFORMÁTICA Director ÁLVARO ESCOBAR ESCOBAR Ingeniero de Sistemas UNIVERSIDAD PILOTO DE COLOMBIA FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍAS, INGENIERÍA DE SISTEMAS POSTGRADOS SANTA FE DE BOGOTÁ 2014 Nota De Aceptación: _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ Firma del Presidente del Jurado ____________________________ Firma del Jurado ____________________________ Firma del Jurado Bogotá, A bril 01 del 2014 “A mi familia por su apoyo A mi novia por su paciencia A la universidad y compañeros por permitir la construcción de nuevo conocimiento” Cristian Castañeda “A mi familia, universidad y amigos” Rodrigo Hernández CONTENIDO pág. 1. PLA NTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA ................................................................ 22 1.1 ENUNCIADO DEL PROBLEMA .......................................................................... 22 1.2 FORMULA CIÓN DEL PROBLEMA ................................................................... -

North Dakota Homeland Security Anti-Terrorism Summary

UNCLASSIFIED NORTH DAKOTA HOMELAND SECURITY ANTI-TERRORISM SUMMARY The North Dakota Open Source Anti-Terrorism Summary is a product of the North Dakota State and Local Intelligence Center (NDSLIC). It provides open source news articles and information on terrorism, crime, and potential destructive or damaging acts of nature or unintentional acts. Articles are placed in the Anti-Terrorism Summary to provide situational awareness for local law enforcement, first responders, government officials, and private/public infrastructure owners. UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED NDSLIC Disclaimer The Anti-Terrorism Summary is a non-commercial publication intended to educate and inform. Further reproduction or redistribution is subject to original copyright restrictions. NDSLIC provides no warranty of ownership of the copyright, or accuracy with respect to the original source material. QUICK LINKS North Dakota Energy Regional Food and Agriculture National Government Sector (including Schools and Universities) International Information Technology and Banking and Finance Industry Telecommunications Chemical and Hazardous Materials National Monuments and Icons Sector Postal and Shipping Commercial Facilities Public Health Communications Sector Transportation Critical Manufacturing Water and Dams Defense Industrial Base Sector North Dakota Homeland Security Emergency Services Contacts UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED North Dakota Westbound lane of Interstate 94 reopened at Painted Canyon. An accident in which a truck transporting a gin pole on a trailer collided with an overpass caused part of the westbound lane on Interstate 94 to close for several hours at the Painted Canyon Overlook exit June 24-25. The overpass was also shut down for several hours while engineers determined the extent of the structural damage. Source: http://www.thedickinsonpress.com/event/article/id/69710/ USDA: Strong storms cause crop damage. -

Balancing Security and Liberty in Cybercrime Law Somaly Nguon and Dr

Cambodia v. Hackers: Balancing Security and Liberty in Cybercrime Law Somaly Nguon and Dr. Sopheak Srun DIGITAL INSIGHTS Photo Credits: Image by Jason Goh from Pixabay Reading time: 11 minutes Cambodia v. Hackers: Balancing Security and Liberty in Cybercrime Law Somaly Nguon1 and Dr. Sopheak Srun2 1 Somaly Nguon is a Researcher in the field of Laws and Technologies. She is a researcher at Tallinn Law School, Tallinn University of Technology (TTU), Estonia and Research Fellow at Center for the Study of Humanitarian Law, Royal University of Law and Economics (RULE), Cambodia. She is a Co-founder and Legal Consultant at Lawtitude Tech OÜ in Tallinn, Estonia. Somaly holds Master in Law and Technology from Tallinn University of Technology in Estonia and Master in International Human Rights from Paññāsāstra University of Cambodia (PUC). She is a lecturer in ICT Law and Cybersecurity course. She conducts extensive legal research and publications in the area of Cybersecurity law and e-Governance. Somaly also represented Cambodia and Tallinn Law School in the framework of Export Academy at Estonian House of Commerce. 2 Dr. Sopheak Srun is a Researcher in the field of Economics and International Trade. For more than seven years, he has been involved in working and managing many projects for both national and international NGOs, public and private sectors, and for foreign embassy. He is familiar with project design and project cycle management as well as in feasibility study and marketing research and evaluation. He holds a PhD degree in Economics from the University of Toulon and a Master degree of Business and Economic from the University of Lumière Lyon 2, both are in France. -

Technical Report RHUL–ISG–2021–1 10 March 2021

The Computer Misuse Act and Hackers: A review of those convicted under the Act James Crawford Technical Report RHUL–ISG–2021–1 10 March 2021 Information Security Group Royal Holloway University of London Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX United Kingdom Student Number: 100910920 James Crawford The Computer Misuse Act and Hackers: A review of those convicted under the Act Supervisor: Dr. Rikke Bjerg Jensen Submitted as part of the requirements for the award of the MSc in Information Security at Royal Holloway, University of London. I declare that this assignment is all my own work and that I have acknowledged all quotations from published or unpublished work of other people. I also declare that I have read the statements on plagiarism in Section 1 of the Regulations Governing Examination and Assessment Offences, and in accordance with these regulations I submit this project report as my own work. Signature: Date: 24 August 2020 1 Table of Contents: Introduction - p. 3 Chapter 1 - The Computer Misuse Act 1990 - p.5 Chapter 2 – Hackers: An attempt at a definition - p.13 Chapter 3 - Methodology - p.17 Chapter 4 - Skill - p.21 Chapter 5 - Motivations - p.25 Chapter 6 - Demographics - p.34 Chapter 7 - Insiders and Groups - p.38 Chapter 8 - Typologies - p.43 Chapter 9 - Conclusion - p.48 References - p.51 Appendix A - Table of individuals convicted under the CMA. See separate attachment. 2 Introduction The Computer Misuse Act 1990 (hereafter referred to as the CMA) was introduced in order to close the ‘loophole for hackers’ [HC90 col.1135] that had become evident in the United Kingdom throughout the 1980s.