Regional Cyber Security: Moving Towards a Resilient ASEAN Cyber Security Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion–State Relations

Religion–State Relations International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 8 Religion–State Relations International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 8 Dawood Ahmed © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-113-2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages and risks ............................................................................................... -

Reporting, and General Mentions Seem to Be in Decline

CYBER THREAT ANALYSIS Return to Normalcy: False Flags and the Decline of International Hacktivism By Insikt Group® CTA-2019-0821 CYBER THREAT ANALYSIS Groups with the trappings of hacktivism have recently dumped Russian and Iranian state security organization records online, although neither have proclaimed themselves to be hacktivists. In addition, hacktivism has taken a back seat in news reporting, and general mentions seem to be in decline. Insikt Group utilized the Recorded FutureⓇ Platform and reports of historical hacktivism events to analyze the shifting targets and players in the hacktivism space. The target audience of this research includes security practitioners whose enterprises may be targets for hacktivism. Executive Summary Hacktivism often brings to mind a loose collective of individuals globally that band together to achieve a common goal. However, Insikt Group research demonstrates that this is a misleading assumption; the hacktivist landscape has consistently included actors reacting to regional events, and has also involved states operating under the guise of hacktivism to achieve geopolitical goals. In the last 10 years, the number of large-scale, international hacking operations most commonly associated with hacktivism has risen astronomically, only to fall off just as dramatically after 2015 and 2016. This constitutes a return to normalcy, in which hacktivist groups are usually small sets of regional actors targeting specific organizations to protest regional events, or nation-state groups operating under the guise of hacktivism. Attack vectors used by hacktivist groups have remained largely consistent from 2010 to 2019, and tooling has assisted actors to conduct larger-scale attacks. However, company defenses have also become significantly better in the last decade, which has likely contributed to the decline in successful hacktivist operations. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Romano-OP with Green.Indd

September 2007 Occasional Paper Occasional An Outline of Kurdish Islamist Groups in Iraq David Romano Abstract: This article outlines the history and genesis of Kurdish Islamist groups in Iraq. Based on fi eldwork and personal interviews conducted in Iraq in 2003 and 2004, this study presents a signifi cant amount of never-before published details about these movements. Particular attention is paid to the links between various groups, their transformation or splintering into new organizations, and the role of the non-Kurdish Iraqi Muslim Brotherhood in spawning these movements. The conclusion to this study addresses possible strategies for containing radical Islamist movements, and the dilemmas inherent in constructing such strategies. Th e Jamestown Foundation’s Mission Th e mission of Th e Jamestown Foundation is to inform and educate policymakers and the broader policy community about events and trends in those societies that are strategically or tactically important to the United States and that frequently restrict access to such information. Utilizing indigenous and primary sources, Jamestown’s material is delivered without political bias, fi lter or agenda. It is often the only source of information that should be, but is not always, available through offi cial or intelligence channels, especially in regard to Eurasia and terrorism. * * * * * * * * * * * Occasional Papers are essays and reports that Th e Jamestown Foundation believes to be valuable to the policy community. Th ese papers may be created by analysts and scholars associated with Th e Jamestown Foundation or as the result of a conference or event sponsored or associated with Th e Jamestown Foundation. Occasional Papers refl ect the views of their authors, not those of Th e Jamestown Foundation. -

Democracy Denied, Youth Participation and Criminalizing Digital Dissent

Journal of Youth Studies ISSN: 1367-6261 (Print) 1469-9680 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjys20 Democracy denied, youth participation and criminalizing digital dissent Judith Bessant To cite this article: Judith Bessant (2016) Democracy denied, youth participation and criminalizing digital dissent, Journal of Youth Studies, 19:7, 921-937, DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1123235 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1123235 Published online: 13 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 206 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjys20 Download by: [University of Liverpool] Date: 12 October 2016, At: 02:53 JOURNAL OF YOUTH STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 19, NO. 7, 921–937 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1123235 Democracy denied, youth participation and criminalizing digital dissent Judith Bessant School of Global, Urban & Social Studies, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Attention is given in this article to recent action by many liberal Received 1 May 2015 states to regulate and criminalize certain forms of political dissent Accepted 18 November 2015 reliant on new media. I ask how those working in the fields of KEYWORDS youth studies and social science more generally might understand Citizenship; media; politics; such processes of criminalizing political dissent involving young crime people digital media. I do this mindful of the prevailing concern about a ‘crisis in democracy’ said to be evident in the withdrawal by many young people from traditional forms of political engagement, and the need to encourage greater youth participation in democratic practices. -

Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: the Albu Fahd Tribe

Iraq Tribal Study AL-ANBAR GOVERNORATE ALBU FAHD TRIBE ALBU MAHAL TRIBE ALBU ISSA TRIBE GLOBAL GLOBAL RESOURCES RISK GROUP This Page Intentionally Left Blank Iraq Tribal Study Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: The Albu Fahd Tribe, The Albu Mahal Tribe and the Albu Issa Tribe Study Director and Primary Researcher: Lin Todd Contributing Researchers: W. Patrick Lang, Jr., Colonel, US Army (Retired) R. Alan King Andrea V. Jackson Montgomery McFate, PhD Ahmed S. Hashim, PhD Jeremy S. Harrington Research and Writing Completed: June 18, 2006 Study Conducted Under Contract with the Department of Defense. i Iraq Tribal Study This Page Intentionally Left Blank ii Iraq Tribal Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER ONE. Introduction 1-1 CHAPTER TWO. Common Historical Characteristics and Aspects of the Tribes of Iraq and al-Anbar Governorate 2-1 • Key Characteristics of Sunni Arab Identity 2-3 • Arab Ethnicity 2-3 – The Impact of the Arabic Language 2-4 – Arabism 2-5 – Authority in Contemporary Iraq 2-8 • Islam 2-9 – Islam and the State 2-9 – Role of Islam in Politics 2-10 – Islam and Legitimacy 2-11 – Sunni Islam 2-12 – Sunni Islam Madhabs (Schools of Law) 2-13 – Hanafi School 2-13 – Maliki School 2-14 – Shafii School 2-15 – Hanbali School 2-15 – Sunni Islam in Iraq 2-16 – Extremist Forms of Sunni Islam 2-17 – Wahhabism 2-17 – Salafism 2-19 – Takfirism 2-22 – Sunni and Shia Differences 2-23 – Islam and Arabism 2-24 – Role of Islam in Government and Politics in Iraq 2-25 – Women in Islam 2-26 – Piety 2-29 – Fatalism 2-31 – Social Justice 2-31 – Quranic Treatment of Warfare vs. -

“We Can Do Very Little with Them”1: British Discourse and British Policy on Shi'is in Iraq Heath Allen Furrow Thesis Submi

“We can do very little with them”1: British Discourse and British Policy on Shi‘is in Iraq Heath Allen Furrow Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Carmen M. K. Gitre (Chair) Danna Agmon Brett L. Shadle 9 May 2019 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Iraq, Imperialism, Religion, Christianity, Islam 1 “Gertrude Bell to Sir Hugh Bell, 10 July 1921,” Gertrude Bell Archive, Newcastle University, http://gertrudebell.ncl.ac.uk/letters.php. “We can do very little with them”2: British Discourse and British Policy on Shi‘is in Iraq Heath Allen Furrow Abstract This thesis explores the role of metropolitan religious values and discourses in influencing British officials’ discourse on Sunni and Shi‘i Islam in early mandate Iraq. It also explores the role that this discourse played in informing the policy decisions of British officials. I argue that British officials thought about and described Sunni and Shi‘i Islam through a lens of religious values and experiences that led British officials to describe Shi‘i Islam as prone to theocracy and religious and intellectual intolerance, traits that British officials saw as detrimental to their efforts to create a modern state in Iraq. These descriptions ultimately led British officials to take active steps to remove Shi‘i religions leaders from the civic discourse of Iraq and to support an indigenous government where Sunnis were given most government positions in spite of making up a minority of the overall population of Iraq. -

Black Flags from the East - P63 the Flag - P63 Brief History - P64 AQ's Goals - P64 Owning the Resistance - P65 the Instability-Fix Technique - P65

1 It was narrated from Abu Hurayrah that the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said: “Towards the end of time, hardly any dream of a Muslim will be false. The ones who have the truest dreams will be those who are truest in speech. The dream of a Muslim is one of the forty-five parts of Prophethood. Dreams are of three types: a good dream which is glad tidings from Allaah, a dream from the Shaytaan which causes distress, and a dream that comes from what a man is thinking of to himself…” (Sahih Muslim 2263) And the disbelievers planned, but Allah (God) also planned. And Allah is the best of planners. (Quran 3:54) Khurasan: The Land of Narrow Mountain passes, vast open spaces, thick forests, caves, and the Pamir maze ‘the roof of the world’ which opens the (hidden) gateway to the rest of the middle world. The narrow mountain passes for preventing huge armies. The vast open spaces to expose the enemy and give him no place to hide. The thick forests and caves to hide your own men and weapons. And the amazing Pamir maze – territory of the Muslim fighters, where you can hide, regroup, or simply travel to any country of your choice, without any borders in your way. The land Allah (God) would choose for the preparation of the ‘Battles of the End of Time.’ 2 Contents Introduction: The Boy's Dream – p7 Part 1 - 1979-1989 – a new Islamic century. The Afghan Jihad against Russia – p9 Abdullah Azzam – p9 Osama’s first visit to Afghanistan – p11 Russia loses – p12 The early Taliban - p14 Block the Supply Routes Strategy: - p15 Part 2 - (1989-2000) - the Foundation of the Movement The Foundation (Qa'idah) of AQ (Al Qa’idah) & The Afghan Civil War - p16 1990-1996:-Osama's return to Saudi Arabia - p17 The Move to Sudan. -

Political Islam Among the Kurds

POLITICAL ISLAM AMONG THE KURDS Michiel Leezenberg University of Amsterdam Paper originally prepared for the International Conference ‘Kurdistan: The Unwanted State’, March 29-31, 2001, Jagiellonian University/Polish-Kurdish Society, Cracow, Poland 1. Introduction The theme of Islam is not very prominent or popular when it comes to writings about the Kurds. Political analyses of Kurdish nationalism tend, almost as a matter of definition, to downplay religious aspects, which the Kurds by and large have in common with Political Islam among the Kn ethnic factors like language that mark off the Kurds.1 Further, Kurdish nationalists tend to argue that the Kurds were forcibly converted to Islam, and that the ‘real’ or ‘original’ religion of the Kurds was the dualist Indo-Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism; this religion, it is further alleged, lives on in sects like the Yezidis and the Kakais or Ahl-e Haqq, which are thus portrayed as more quintessentially Kurdish than the Sunni Islam to which most Kurds adhere. Likewise, foreign scholars often have a particular interest in the more exotic and colorful heterodox sects in Kurdistan, which has resulted in a disproportionate amount of attention devoted to groups like the Yezidis, the Ahl-e Haqq, and the Alevis, not to mention the Christian and Jewish groups that live (or used to live) in the region. This is not to criticize such valuable and often very interesting research, but merely to state that much of the beliefs and practices of the Kurds, the vast majority of whom are orthodox Sunni muslims, -

Cyber News for Counterintelligence / Information Technology / Security Professionals 18 June 2014

Cyber News for Counterintelligence / Information Technology / Security Professionals 18 June 2014 Purpose June 17, Softpedia – (International) Evernote’s forum server has been hacked. Educate recipients of cyber events to aid in protecting Evernote advised certain users to change their passwords for the company’s forum electronically stored DoD, after attackers were able to access the forum server, potentially exposing hashed corporate proprietary, and/or Personally Identifiable passwords as well as email addresses and birthdays if users provided them. Those Information from theft, affected are users with forum accounts created in 2011 or earlier. Source: compromise, espionage http://news.softpedia.com/news/Evernote-s-Forum-Server-Has-Been-Hacked- Source 447035.shtml This publication incorporates open source news articles educate readers on security June 16, SC Magazine – (International) Technology sites “riskier” than illegal sites matters in compliance with in 2013, according to Symantec data. Symantec researchers released a post based USC Title 17, section 107, on Norton Web Safe user data that found that technology Web sites were the Para a. All articles are truncated to avoid the riskiest category of site to visit in 2013 based on the amount of malware and fake appearance of copyright antivirus attempts utilizing that category of sites to attempt to infect users. infringement Source: http://www.scmagazine.com/technology-sites-riskier-than-illegal-sites-in- Publisher 2013-according-to-symantec-data/article/355982/ * SA Jeanette Greene Albuquerque FBI June 16, Softpedia – (International) Internet Explorer script engine susceptible to Editor * CI SA Scott Daughtry attacks. A researcher with Fortinet reported that the script engine in Microsoft DTRA Counterintelligence Internet Explorer is potentially vulnerable to attacks via changing a security flag in Subscription Jscript or VBScript. -

The Dynamics of Iraq's Media: Ethno-Sectarian Violence, Political

CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR POLICY STUDIES OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE IBRAHIM AL-MARASHI The Dynamics of Iraq’s Media: Ethno-Sectarian Violence, Political Islam, Public Advocacy and Globalization 7 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 CPS INTERNATI O N A L P O L I C Y FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM IBRAHIM AL-MARASHI The Dynamics of Iraq’s Media: Ethno-Sectarian Violence, Political Islam, Public Advocacy, and Globalization Abstract A recurring theme in debates on the future of Iraq is that the state is facing an imminent civil war among ethnic Kurds, Turkmens and Arabs, and among the Sunni and Shi’a Muslim sects. As tensions continue to escalate, the Iraqi media will play a crucial role in these developments. The pluralization of a private media sector in post-Ba’athist Iraq has serve as a positive development in Iraq’s post-war transition, yet this has also allowed for the emergence of local media that are forming along ethno-sectarian lines. The Iraqi media have evolved to a stage where they now have the capability of reinforcing the country’s ethno-sectarian divisions. This policy paper examines the evolution and current state of Iraq’s media and offer recommendations to local Iraqi actors, as well as regional and international organizations as to how the media can counter employment of negative images and stereotypes of other ethno-sectarian communities and influence public attitudes in overcoming such tensions in Iraqi society. This policy paper was produced under the 2006-07 International Policy Fellowship program. Ibrahim Al-Marashi was a member of `Open Society Promotion in Predominantly Muslim Societies` working group, which was directed by Kian Tajbakhsh. -

Breach Report 2012.Pdf

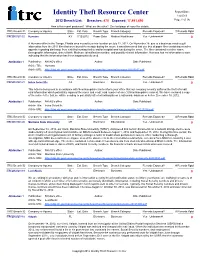

Identity Theft Resource Center Report Date: 1/4/2013 2012 Breach List: Breaches: 470 Exposed: 17,491,690 Page 1 of 95 How is this report produced? What are the rules? See last page of report for details. ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency State Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Records Exposed? # Records Rptd ITRC20121231-22 Humana KY 7/12/2012 Paper Data Medical/Healthcare Yes - Unknown # 0 A Humana office in the Tampa, Florida area moved to a new location on July 12, 2012. On November 28, due to a business need to pull information from the 2011 files that were boxed for storage during the move, it was discovered that one box of paper files containing member appeals regarding discharge from a skilled nursing facility and/or hospital was lost during the move. The files contained member name, demographic information, date of birth, Medicare identification number, and possibly clinical information. Humana has no information to date indicating that the information has been inappropriately used. Attribution 1 Publication: NH AG's office Author: Date Published: Article Title: Humana Article URL: http://doj.nh.gov/consumer/security-breaches/documents/humana-20121217.pdf ITRC Breach ID Company or Agency State Est. Date Breach Type Breach Category Records Exposed? # Records Rptd ITRC20121231-21 Irvine Scientific CA Electronic Business Yes - Unknown # 0 This letter is being sent in accordance with New Hampshire law to inform your office that our company recently suffered the theft of credit card information which potentially exposed the name and credit card number of one (1) New Hampshire resident.