Stephens, Liz 10-25-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2007 Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry" (2007). Court Green. 4. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. court green 4 Court Green is published annually at Columbia College Chicago Court Green Editors: Arielle Greenberg, Tony Trigilio, and David Trinidad Managing Editor: Cora Jacobs Editorial Assistants: Ian Harris and Brandi Homan Court Green is published annually in association with the English Department of Columbia College Chicago. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair of the English Department; Dominic Pacyga, Interim Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Steven Kapelke, Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. “The Late War”, from The Complete Poems of D.H. Lawrence by D.H. Lawrence, edited by V. de Sola Pinto & F. W. Roberts, copyright © 1964, 1971 by Angelo Ravagli and C. M. Weekley, Executors of the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. “In America” by Bernadette Mayer is reprinted from United Artists (No. -

Bullseye Glass Catalog

CATALOG BULLSEYE GLASS For Art and Architecture IMPOSSIBLE THINGS The best distinction between art and craft • A quilt of color onto which children have that I’ve ever heard came from artist John “stitched” their stories of plants and Torreano at a panel discussion I attended a animals (page 5) few years ago: • A 500-year-old street in Spain that “Craft is what we know; art is what we don’t suddenly disappears and then reappears know. Craft is knowledge; art is mystery.” in a gallery in Portland, Oregon (page 10) (Or something like that—John was talking • The infinite stories of seamstresses faster than I could write). preserved in cast-glass ghosts (page 25) The craft of glass involves a lifetime of • A tapestry of crystalline glass particles learning, but the stories that arise from that floating in space, as ethereal as the craft are what propel us into the unknown. shadows it casts (page 28) At Bullseye, the unknown and oftentimes • A magic carpet of millions of particles of alchemical aspects of glass continually push crushed glass with the artists footprints us into new territory: to powders, to strikers, fired into eternity (page 31) to reactive glasses, to developing methods • A gravity-defying vortex of glass finding like the vitrigraph and flow techniques. its way across the Pacific Ocean to Similarly, we're drawn to artists who captivate Emerge jurors (and land on the tell their stories in glass based on their cover of this catalog) exceptional skills, but even more on their We hope this catalog does more than point boundless imaginations. -

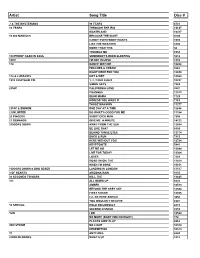

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Winter 2015 • Volume24 • Number4

Winter 2015 • Volume24 • Number4 If Disney Files Magazine was a grocery store tabloid, the headline on this edition’s cover may read: Giant Reptile to Terrorize China! Of course, we’d never resort to such sensationalism, even if we are ridiculously excited about the imposing star of the Roaring Rapids attraction in the works for Shanghai Disneyland (pages 3-8). We take ourselves far too seriously for such nonsense. Wait a minute. What am I saying? This isn’t exactly a medical journal, and anyone who’s ever read the fine print at the bottom of this page knows that, if there’s one thing we embrace in theDisney Files newsroom, it’s nonsense! So at the risk of ending our pursuit of a Pulitzer (close as we were), I introduce this issue with a series of headlines crafted with all the journalistic integrity of rags reporting the births of alien babies, celebrity babies…and alien-celebrity babies. Who wore it best? Disney’s Beach Club Villas vs. the Brady family! (Page 13) Evil empire mounting Disney Parks takeover! (Pages 19-20) Prince Harry sending soldiers into Walt Disney World battle! (Page 21) An Affleck faces peril at sea! (Page 24) Mickey sells Pluto on the street! (Page 27) Underage driver goes for joy ride…doesn’t wear seatbelt! (Page 30) Somewhere in Oregon, my journalism professors weep. All of us at Disney Vacation Club wish you a happy holiday season and a “sensational” new year. Welcome home, Ryan March Disney Files Editor Illustration by Keelan Parham VOL. 24 NO. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNDERNEATH, DEEP DOWN: A COLLECTION OF SHORT STORIES YARDYN SHRAGA SPRING 2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: William Cobb Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This project considers the lives of seemingly anonymous passersby on public transport in various cities around the world. These stories deal with love; loss; the manifestation and transcendence of souls; growth; coming of age; coming into connection with oneself, as well as the world. The following collection is ultimately aimed at encouraging each reader to pause and consider other lives that often seem inconsequential. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... iii Reflective Essay ........................................................................................................... iv Author’s Note............................................................................................................... 1 I. New York City.......................................................................................................... 2 II. Paris ........................................................................................................................ -

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II a Thesis Submitted To

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II A thesis submitted to: Lakehead University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts Matthew Sitter Thunder Bay, Ontario July 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Restless Heart

RESTLESS HEART Restless Heart lead singer Larry Stewart can remember the exact moment and place his life began to change forever. “I was driving east on I-40 from West Nashville into town to an appointment,” he recalls. “Back then, I was listening to what we were doing in my Jeep Cherokee every day. I had turned the radio on, and ‘Let The Heartache Ride’ was right in the middle of the acapella intro.” Stewart had been living with the song for a while, and hearing it through his car speakers wasn’t that big of a deal – until he looked at the stereo and saw the numbers 97.9. “It didn’t sink in because I had it in the tape deck for days, then I realized ‘That’s the radio. It’s WSIX.’ I pulled over on the shoulder around White Bridge Road and sat there with my car idling. It was like yesterday.” ‘Yesterday’ has come full circle for Restless Heart. Then one of Nashville’s newest acts, the band is celebrating their 30th Anniversary in 2013, and Dave Innis enjoys the musical ride as much as ever. “I think it’s been an amazing legacy, and it’s been such an honor to have been part of an organization that is still together doing it after thirty years with the same five original guys, and it’s more fun than ever.” John Dittrich, Greg Jennings, Paul Gregg, Dave Innis, and Larry Stewart – the men who make up Restless Heart have enjoyed one of the most successful careers in Country Music history, placing over 25 singles on the charts – with six consecutive #1 hits, four of their albums have been certified Gold by the RIAA, and they have won a wide range of awards from many organizations – including the Academy of Country Music’s Top Vocal Group trophy. -

To Be a Man Gina Wohlsdorf Charlottesville, Virginia

To Be a Man Gina Wohlsdorf Charlottesville, Virginia Bachelor of Arts, Tulane University, 2003 A thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in candidacy for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Department of English University of Virginia December, 2013 ii © 2013 Gina Wohlsdorf 1 BASIC ECONOMICS Your children probably aren’t dead. That was the gist of the cops’ information. “We don’t have a clear understanding of the situation at this time,” said Sergeant Kennison. “You know what we know. Try to be patient.” The shooting started at one o’clock. Word spreads fast in the suburbs, especially when every teenager who’s any teenager owns a cell phone. The police set up a check- point at an old folk’s home that specialized in Alzheimer’s – beautiful facility with a top- flight staff. They set cookies, coffee and a jug of juice by a wide view of rolling hills. We ignored the snacks. We looked at a hill. Two-hundred yards away, red and blue lights flashed in front of a glass house. I asked Sadie once why Horizon High had so many windows. “It’s a cost savings measure,” she told me. “Sunlight reduces the electric bill.” Her lopsided smile slammed through my memories like a pickaxe. “But you’re asking an Econ teacher. If you’d married Miss Gilbert in Art, she’d have told you they’re ravishing.” One o’clock was fifth period, which Sadie had free. Her turn for hall patrol in Wing E: no smoking in the boy’s room, no loitering. -

That Glistens Is...Time

Inspired by his students, Dr. K. rejoins the battle of ideas, after many years of self-imposed professional exile. They take action after hearing his revolutionary theory of a digital substitute for currency. If universally adopted, Work Units, (WU) could replace all of the world's failing currencies. Dr. K.'s new-found popularity elicits the unwanted attention of the global elite's minions: the Department of Defense, the U.S. Senate and the multi-national media empire Omni Orion Group. All That Glitters is… TIME Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/5921.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Your Free excerpt appears below. Enjoy! Copyright © 2011 Eric Crews Hardcover ISBN 978-1-61434-743-9 Paperback ISBN 978-1-61434-744-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published in the United States by Booklocker.com, Inc., Bangor, Maine. The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2011 First Edition Chapter 1 You Never Give Me Your Money: 1-3 Lennon & McCartney ulie bounded up the steps to the third floor, two at a time. Her long strides powered by legs trained these past few years by a grueling J schedule of track and field.