From The'little Aussie Bleeder'to Newstopia:(Really) Fake News In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

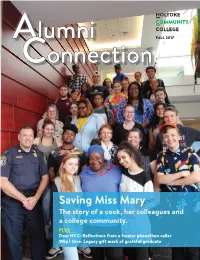

Saving Miss Mary the Story of a Cook, Her Colleagues and a College Community

Alumni FALL 2017 Connection Saving Miss Mary The story of a cook, her colleagues and a college community. PLUS Dear HCC: Reflections from a former phonathon caller Why I Give: Legacy gift mark of grateful graduate DEAR READERS early every day I hear something that makes me proud of Holyoke Community College. Whether speaking Nwith a student who found her path and passion with the support of a faculty mentor, or meeting with our Open Alumni Educational Resources team, a group of faculty and staff working to drastically cut the cost of books and educational materials for our students, the sense of community and the transformative Connection power of our mission are unmistakable. In the year ahead, HCC will embark on a strategic planning The Alumni Connection is published two times process that will bring students, faculty, staff, alumni and per year by the Holyoke Community College community stakeholders together to envision and plan the future Alumni Office, Holyoke, Massachusetts, and of HCC. What are the most pressing needs of our students and is distributed without charge to alumni and our community? What are our unique strengths and how do we friends of HCC. Third-class postage is paid at Christina Royal, Ph.D., want to build upon them? How can we invest our resources in Springfield, Massachusetts. HCC President order to have the greatest impact? This is a pivotal moment for HCC, and I hope you will join us in this undertaking. To learn more Editors: about the planning process and how you can participate, please JoAnne L. Rome and Chris Yurko visit hcc.edu/forward. -

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

Anna Karpinski CV 2

A N N A K A R P I N S K I Make-up Artist Booking Agent: Freelancers Promotions. p. +61 3 9682 2772 e. [email protected] w. www.freelancers.com.au Since studying at 3 Arts make-up college in 1984, I have worked continuously in the film industry. My career encompasses feature films, television, documentaries, television commercials, corporates, special effects and stills. Below is an edited version of my work history……… FILM & TV SERIES 2014-15 Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries Every Cloud Productions Make-up Designer Series 3 Cast: Essie Davis;Miriam ABC TV Series Margolyes; Nathan Page;Ashleigh Cummings;Hugo Johnston-bert 2014 Nowhere Boys Matchbox Pictures Make-up Designer Series 2 cast:Michala ABC 3 TV Series Banas;Victoria Thaine; Dougie Baldwin; 2014 Upper Middle Bogan Gristmill Make-up Designer Series 2 cast:Robyn Nevin;Annie ABC TV Series Maynard;Robyn Malcombe;Patrick Brammall;Michala Banas;Glen Robbins 2014 The Time Of Our Lives JAHM Pictures Make-up Designer Series 2 cast:Claudia Karvan; ABC TV Series William McIness; Justine Clarke;Shane Jacobson;Stephen Curry 2013 Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries Every Cloud Productions Make-up Designer Series 2 cast:Essie Davis ABC TV Series Ashleigh Cummings 2013 Mr & Mrs Murder Fremantle Media Make-up Designer TV Series cast Shaun Micallef Kat Stewart;Lucy Honingman 2012 HOWZAT! Southern Star Make-up Designer Chn 9 Mini Series cast Lachie Hulme;Abe Forsythe;Damon Gameau 2011 Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries Every Cloud Productions Make-up Designer Series 1 cast;Essie Davis TV Series 2011 Woodley ABC Make-up Designer Comedy TV Series cast;Frank Woodley Justine Clarke 2010 City Homicide Series 4 7 Network Make-up Supervisor chn7 TV Series cast:Nadine Garner;Aaron Pederson;Noni Hazelhurst;David Field 2009 Dead Gorgeous Burberry / BBC Make-up Designer TV Series 2009 Satisfaction Lonehand / Showtime Make-up Designer Series 3 cast:Dianna Glenn TV Series Madeline West;Alison Whyte; FILM & TV SERIES Cont…. -

Open Tues-Fri 10Am-5Pm Weekends 12-4Pm Corner Kembla & Burelli

open Tues-Fri 10am-5pm Wollongong Art Gallery is a service of Wollongong City weekends 12-4pm Council and receives assistance from the NSW Government Corner Kembla & Burelli through Create NSW. Wollongong Art Gallery is a member streets Wollongong of Regional and Public Galleries of NSW. phone 02 4227 8500 www.wollongongartgallery.com www.facebook/wollongongartgallery When I think of television, I automatically think of my youth. It’s a time machine set for 1985. Jana Wendt and her big hair interviewing style Simon Townsend and his sad looking dog Being afraid of Norman Gunston And bewildered by Jeanne Little If nostalgia was an object it would be a TV Guide. The bible for the week - Graffitied in black marker so the days, nights and weekends were planned, Watched and then forgotten - Only to be remembered many years later at the pub, When new friends bonded by Recounting soap opera theme songs or word for word advertising jingles. The big box housing the television was Saturday’s dusting date with Mr Sheen and we danced upon that chipboard veneer and elegantly glided over the glass. Pleasure Drill, 2018, Two channel digital video with sound Videographer: Dara Gill. Special thanks to Michael and Di Kershaw. Courtesy of the artist As an indicator of how life could be represented, measured and performed - The TV was my sometimes stand-in for divorcing parents. Loving fictional families were there to council you, cover you cosy - Pleasure Drill is a two channel video that explores the false many years of failed applications to be part of the TV show The In a 30-minute hug. -

Abc Friends Salutes Four Corners

UpdateDecember 2016 Vol 24, No. 3 Thrice Yearly Newsletter ABC FRIENDS SALUTES FOUR CORNERS t the Annual Award questions of the medical profession. Presentation for Broadcasting Even in her illness, Liz was still the AExcellence on Friday 25th relentless investigative reporter. November, ABC Friends (National) It is these qualities, along with recognised the extraordinary persistence, patience, integrity, contribution of Four Corners to curiosity, thoroughness, balance and Australian life and investigative compassion, the hallmarks of great journalism of the highest quality journalism, that have undoubtedly over the past 55 years. Throughout been a thorn in the side of politicians those 55 years, Four Corners has of all persuasions, and those in consistently and with commendable positions of power and authority courage shone a light into many who have been under the relentless dark places in our national life, and microscope of a Four Corners has, without any doubt, investigation. Very recent examples changed Australia for the come to mind: “Broken Homes” better. The final program examined our totally inadequate and for 2016, A Sense of misnamed Child Protection System; Self, was no exception. and her persistent search for the “The Forgotten Children” painfully Liz Jackson, multi-award best medical options with her documented the evaporation of hope winning journalist with Four partner Martin Butler, displaying amongst refugee children under Corners for 30 years, laid exceptional courage, honesty and detention on Nauru; “Australia’s bare her private and family professionalism. In so doing, she Shame”, in graphic detail, showed life in documenting her struggle with taught us all how to be better patients, the onset of Parkinson’s Disease better carers, and to ask the right Continued on Page 4. -

'They're My Two Favourites' Versus' the Bigger Scheme of Things': Pro-Am

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: McKee, Alan & Keating, Chris (2012) ’They’re my two favourites’ versus ’the bigger scheme of things’: Pro-am historians remember Australian television. In Turnbull, S & Darian-Smith, K (Eds.) Remembering television: Histories, technologies, memories. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, United Kingdom, pp. 52-73. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/54554/ c Copyright 2012 Alan McKee & Chris Keating This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.c-s-p.org/ flyers/ Remembering-Television--Histories--Technologies--Memories1-4438-3970-1. -

Stephen Harrington Thesis

PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE BEYOND JOURNALISM: INFOTAINMENT, SATIRE AND AUSTRALIAN TELEVISION STEPHEN HARRINGTON BCI(Media&Comm), BCI(Hons)(MediaSt) Submitted April, 2009 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology, Australia 1 2 STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made. _____________________________________________ Stephen Matthew Harrington Date: 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changing relationships between television, politics, audiences and the public sphere. Premised on the notion that mediated politics is now understood “in new ways by new voices” (Jones, 2005: 4), and appropriating what McNair (2003) calls a “chaos theory” of journalism sociology, this thesis explores how two different contemporary Australian political television programs (Sunrise and The Chaser’s War on Everything) are viewed, understood, and used by audiences. In analysing these programs from textual, industry and audience perspectives, this thesis argues that journalism has been largely thought about in overly simplistic binary terms which have failed to reflect the reality of audiences’ news consumption patterns. The findings of this thesis suggest that both ‘soft’ infotainment (Sunrise) and ‘frivolous’ satire (The Chaser’s War on Everything) are used by audiences in intricate ways as sources of political information, and thus these TV programs (and those like them) should be seen as legitimate and valuable forms of public knowledge production. -

The Problem with Borat

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 9 December 2007 The rP oblem with Borat Ghada Chehade Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation Chehade, G. (2017). The rP oblem with Borat. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.31390/ taboo.11.1.09 Taboo, Spring-Summer-Fall-WinterGhada Chehade 2007 63 The Problem with Borat Ghada Chehade There is just something about Borat, Sacha Baron Cohen’s barbaric alter-ego who The Observer’s Oliver Marre (2006) aptly describes as “…homophobic, rac- ist, and misogynist as well as anti-Semitic.” While on the surface, Cohen’s Borat may seem to offend all races equally—the one group he offends the most is the very group he portrays as homophobic, racist, misogynist, and anti-Semitic. Or in other words, the real parties vilified by Cohen are not Borat’s victims but Borat himself. The humour is ultimately directed at this uncivilized buffoon-Borat. He is the butt of every joke. He is the one we laugh at, and are intended to laugh at, the most inasmuch as he is more vulgar, savage, ignorant, barbaric, and racist than any of the bigoted Americans “exposed” in the 2006 film Borat: Cultural Learn- ings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. This would not be quite as problematic if the fictional Borat did not come from a very real place and did not so obviously (mis)represent Muslims. While the 2006 film has received coverage and praise for revealing the racism of Americans, very few people are asking whether Cohen’s caricature of a savage, homophobic, misogynist, racist, and hard core Jew-hating Muslim is not actually a form of anti-Muslim racism. -

Julian Morrow

Julian Morrow Co-founder of The Chaser; Entertaining MC and speaker Julian Morrow is a comedian and television producer and is best known for being a member of the satirical team The Chaser. Julian has made a career of public nuisance in various forms, co-founding satirical media empire The Chaser and joke company Giant Dwarf, as well as making TV shows including The Election Chaser, CNNNN, The Chaser’s War on Everything, The Hamster Wheel and The Checkout. His work has been nominated, unsuccessfully, for many awards, and prosecuted successfully in many courts. More about Julian Morrow: In recent years, he was taken to claiming credit for the work of others as Executive Producer of Lawrence Leung’s series Choose Your Own Adventure and Unbelievable, Eliza and Hannah Reilly’s Growing Up Gracefully and Sarah Scheller & Alison Bell’s The Letdown (which on the 2018 AACTA Award for Best TV Comedy). In 2012 and 2013 he lowered standards at ABC Radio National as host of Friday Drive, a program which led to huge career opportunities for its Monday-Thursday host, Waleed Aly. In 2015, Julian founded Giant Dwarf theatre at 199 Cleveland Street Redfern, a venue which has been described as “absolutely hilarious” by his accountant. Over the years, Julian has interviewed countless people whose cache he tries to cash in on in his CV including Edward Snowden, Christopher Hitchens, Sting, Nobel Peace Prize winner Leymah Gbowee, Marc Newsome and the curator of TED Chris Anderson. Due to the unavailability of several respected media commentators, in 2009 Julian was invited to give the Andrew Olle Media Lecture, an honour he later demeaned by creating The Annual Inaugural Chaser Lecture. -

Two Brothers Running Music Credits

Original Music by Phillip Scott Lyrics: Opening to camera: The film begins with Tom Conti’s Moses Bornstein upside down on screen. The camera begins a slow swivel and zoom in so that it ends up on Moses’ face the right way up, still talking direct to camera. As the camera does its move, Moses speaks to the viewer. Moses: “Okay, the brother … er, our parents died. We’re orphans. We move into a flat, and I look after him for a year, a year and a half… except I’m going crazy. So I leave him with an uncle for three months, except I can’t look the young boy in the face, because I know it’s … it’s really forever. I go to Europe, I write, I publish, I marry … a son… er, maybe three years, a letter arrives. The brother is coming… er, he’s coming by boat, which is what you did in those days. Terrific. He arrives at the docks, Southampton. We station ourselves at the foot of the gangplank, er, we’re early, we’re the first, no one’s come off .. and they start … a lot of people, a lot of people …er, two, maybe three hundred …and every person that comes off … I can’t see him. I can’t see him … did he come off? He must have! People are milling, you know, I, I, I’m in a real panic. Suddenly Barbara darts into the crowd. She’s, she’s got him … she’s holding his hand! But how, how did you recognise him? She stares at me … Moses … he’s just like you … (almost a whisper) … just like you …” The camera cuts to a Citroën pulling into the driveway of a suburban Melbourne house, and the story begins … It will turn out that Moses is, like his brother, unfaithful, and will lose his wife by end of movie, but his brother will provide him with the ending to the screenplay he keeps telling everybody about throughout the movie, a shaggy dog story with a Jewish hero, who wants to be a thief like his father. -

Semaphore Sea Power Centre - Australia Issue 8, 2017 the Royal Australian Navy on the Silver Screen

SEMAPHORE SEA POWER CENTRE - AUSTRALIA ISSUE 8, 2017 THE ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVY ON THE SILVER SCREEN In this day and age, technologies such as smart phones and tablets allow users to film and view video streams on almost any topic imaginable at the convenience of their fingertips. Indeed, most institutions, including the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), promote video streaming as part of carefully coordinated public relations, recruiting and social media programs. In yesteryear, however, this was not a simple process and the creation and screening of news reels, motion pictures and training films was a costly and time consuming endeavor for all concerned. Notwithstanding that, the RAN has enjoyed an ongoing presence on the silver screen, television and more recently the internet on its voyage from silent pictures to the technologically advanced, digital 21st century. The RAN’s earliest appearances in motion pictures occurred during World War 1. The first of these films was Sea Dogs of Australia, a silent picture about an Australian naval officer blackmailed into helping a foreign spy. The film’s public release in August 1914 coincided with the outbreak of war and it was consequently withdrawn after the Minister for Defence expressed security concerns over film footage taken on board the battlecruiser HMAS Australia (I). There was, however, an apparent change of heart following the victory of HMAS Sydney (I) over the German cruiser SMS Emden in November 1914. Australia’s first naval victory at sea proved big news around the globe The Art Brand Productions - The Raider Emden. and it did not take long before several short, silent propaganda films were produced depicting the action.