Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd, MS/Mphil BS/Bsc (Hons) 2021-22 GCU

PhD, MS/MPhil BS/BSc (Hons) GCU GCU To Welcome 2021-22 A forward-looking institution committed to generating and disseminating cutting- GCUedge knowledge! Our vision is to provide students with the best educational opportunities and resources to thrive on and excel in their careers as well as in shaping the future. We believe that courage and integrity in the pursuit of knowledge have the power to influence and transform the world. Khayaali Production Government College University Press All Rights Reserved Disclaimer Any part of this prospectus shall not be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from Government CONTENTS College University Press Lahore. University Rules, Regulations, Policies, Courses of Study, Subject Combinations and University Dues etc., mentioned in this Prospectus may be withdrawn or amended by the University authorities at any time without any notice. The students shall have to follow the amended or revised Rules, Regulations, Policies, Syllabi, Subject Combinations and pay University Dues. Welcome To GCU 2 Department of History 198 Vice Chancellor’s Message 6 Department of Management Studies 206 Our Historic Old Campus 8 Department of Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Studies 214 GCU’s New Campus 10 Department of Political Science 222 Department of Sociology 232 (Located at Kala Shah Kaku) 10 Journey from Government College to Government College Faculty of Languages, Islamic and Oriental Learning University, Lahore 12 Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies 242 Legendary Alumni 13 Department of -

Of 14 24 37072-NA-18718 FAROOQ AH SOFI PROV STORE DRUGJAN DALGATE KHANYAR BAZAAR COMMITEE DRUGJAN BUCHWARA SGR

S No Office Code Proprieter Name Business Unit Name With Business Unit Location Tehsil Association Name Style Address 1 18552-NA-10415 MOHAMMAD ALTAF KANNI SPARE PARTS AND BAGHI NAND SINGH CENTRAL ALL ZAMINDAR & ACCESSORIES/ MS K.B TATOO GROUND SHALTENG SHOPKEEPERS MOTORS ASSOCIATION BAGHI NAND SINGH CHATTABAL 2 18663-NA-11184 SAJAD AHMAD SOFI CROCKERY ,PLASTIC BATAMALOO OPP JEHWAR CENTRAL ALL ZAMINDAR & ,ELECTRONICS/ SAJAD COMPLEX SHALTENG SHOPKEEPERS TRADERS ASSOCIATION BAGHI NAND SINGH CHATTABAL 3 75372-CE-10776 AABID MAQBOOL PROVISION STORE CHOWKER MUJGUND SRINAGAR CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND RICE ETC SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 4 49625-CE-6502 ABRAR HUSSAIN AMAFHH TECHNOLOGY GUND HASSI BHAT CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 5 8323-CE-1204 Fayaz Ahmad Mir S/O Godown Gund Hassibaht CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND Ab.Razaq Mir SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 6 40396-CE-3848 MUBASHIR HUSSAIN MALLA UP LINE ENTERPRISES BAZAR BHATGUND HASSI CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 7 48802-SO-14127 MUSHTAQ AH BHAT GENERAL STORE MUJGUND CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 8 2240-NA-1411 NAZIR AHMAD KANUE OXFORD CEMENT KIRMANI ABAD CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND WORKS/MANUFACTURNG UNIT SOUZAITH SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 9 49624-CE-6500 RAHI PUBLIC SCHOOL EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTE SHALTANG CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 10 87042-CE-11802 TAHIR MAQBOOL ELECTRONICS COMPUTER ETC MUJGUND CENTRAL IQRA TRADE UNION GUND SHALTENG HASSIBHAT LAWAYPORA 11 93946-CE-14560 ALI MOHD MATTA YASIR CROCKERY STORE BEMINA CENTRAL TRADERS ASSOCIATION SHALTENG BEMINA 12 21605-NA-12916 MOHSIN IQBAL GONI PETROL PUMP BEMINA CENTRAL TRADERS ASSOCIATION SHALTENG BEMINA 13 98098-SO-22073 MUZAFAR AH BHAT RAJA ENTERPRISES NOWGAM CHANAPORA/NA TRADE ASSOCIATION TIPORA NOWGAM 14 15111-NA-6310 ALI MOHD SOFI ALI MOHD SOFI MALIK ANGAN,FATEH KHANYAR AL HAMZAH TRADERS & KADAL MANUFACTURERS ASSO. -

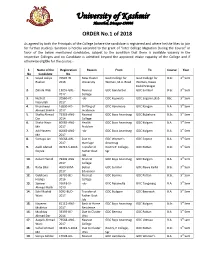

ORDER No.1 of 2018

University of Kashmir Hazratbal, Srinagar-190006 ORDER No.1 of 2018 As agreed by both the Principals of the College (where the candidate is registered and where he/she likes to join for further studies). Sanction is hereby accorded to the grant of “Inter College Migration During the Course” in favor of the below mentioned candidates, subject to the condition that there is available vacancy in the respective Colleges and no Candidate is admitted beyond the approved intake capacity of the College and if otherwise eligible for the course:- S. Name of the Registration Reason From To Course Year No Candidate No. 1. Sayed Aaliya 70597-W- Now Cluster Govt College for Govt College for B.Sc 3rd Sem Raahat 2016 University Women, M.A. Road Women, Nawa Kadal Srinagar 2. Zahida Wali 13055-GBL- Nearest GDC Ganderbal GDC Sumbal B.Sc 3rd Sem 2017 College 3. Nuzhat 20560-KC- -do- GDC Kupwara GDC Sogam Lolab BSc. 3rd Sem Nasrullah 2017 4. Khursheed 16830-HD- Shifting of GDC Handwara GDC Kangan B.A. 3rd Sem Ahmad Sheikh 2017 residence 5. Shafiq Ahmad 75333-ANG- Nearest GDC Boys Anantnag GDC Bijbehara B.Sc. 3rd Sem Dar 2014 College 6. Shakir Nazir 80085-ANG- Health GDC Boys Anantnag GDC Kulgam B.A. 3rd Sem Mir 2017 Problem 7. Adil Yaseen 80083-ANG- -do- GDC Boys Anantnag GDC Kulgam B.A. 3rd Sem Mir 2017 8. Sumaya Jan 36668-AW- Due to GDC Women’s GDC Sopore B.A. 3rd Sem 2017 marriage Anantnag 9. Aadil Ahmad 49715-S-2016 Transfer of Govt S.P. -

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY of KASHMIR List of Eligible Candidates

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR Employment Notification No. 01 of 2018 Dated: 07-02-2018 & 12 of 2016 Dated: 28-12-2016 List of Eligible Candidates Post: MTS/Peon/Office Attendant (02-UR) Post Code: WT-13-2019-CUK Centre Code: G01 & G02 Date of Written Test: 30.06.2019 Session-1: Paper-A (Objective) 02:30pm to 04:00pm Session-2: Paper-B (Descriptive) 04:30pm to 06:00pm Venue: a) Candidates whose Roll No.s from 19131600 to 19132179 shall be at Central University of Kashmir, Green Campus, Opposite Degree College, Ganderbal b) Candidates whose Roll No.s from 19132180-19132274 shall be at Central University of Kashmir, Science & Arts Campus, Old Hospital, Ganderbal- 191201 (J&K) Note: Using below-mentioned Hall Ticket Number, the candidates are informed to download Hall Ticket from the University website w.e.f 28-06-2019 Hall Ticket No. Name of the Applicant Category 19131600 Ms Humira Akhter D/o Mohammad Yousuf Khan UR R/o Iqbal Colony Dialgam Anantnag-192210 19131601 Ms Shahnaza Yousuf D/o Mohammad Yousuf Khan UR R/o Iqbal Colony Dialgam Anantnag-192210 19131602 MsCell:871599247/9596439917 Bismah Rashid D/o Abdul Rashid UR R/o Shaheed Gunj Near Custodian Office Srinagar-190001 19131603 MsCell:9797930029/9622511370 Tabasum Rashid D/o Abdul Rashid Khan UR R/o Shaheed Gunj Near Custodian Office Srinagar-190001 19131604 MrCell:9622829426 Zahoor Ahmad Shan S/o Ali Mohd Shan UR R/o Zungalpora Pahloo Kulgam-192231 19131605 MrCell:9622726400/9797037173 Idrees Hussain Khan S/o Nasir Hussain Khan UR R/o Hassan Abad Rainawari Srinagar-190003 19131606 -

Kashmir Council-Eu Kashmir Council-Eu

A 004144 02.07.2020 KASHMIR COUNCIL-EU KASHMIR COUNCIL-EU Mr. David Maria SASSOLI European Parliament Bât.PAUL-HENRI SPAAK 09B011 60, rue Wiertz B-1047 Bruxelles June 1, 2020 Dear President David Maria SASSOLI, I am writing to you to draw your attention to the latest report released by the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition on Civil Society (JKCCS) and Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) which documents a very dire human rights situation in Indian-Administered Kashmir, due to the general breakdown of the rule of law. The report shows that at least 229 people were killed following different incidents of violence, including 32 civilians who lost their life due to extrajudicial executions, only within a six months period, from January 1, 2020, until 30 June 2020. Women and children who should be protected and kept safe, suffer the hardest from the effects of the conflict, three children and two women have been killed over this period alone. On an almost daily basis, unlawful killings of one or two individuals are reported in Jammu and Kashmir. As you may be aware, impunity for human rights abuses is a long-standing issue in Jammu and Kashmir. Abuses by security force personnel, including unlawful killings, rape, and disappearances, have often go ne uninvestigated and unpunished. India authorities in Jammu and Kashmir also frequently violate other rights. Prolonged curfews restrict people’s movement, mobile and internet service shutdowns curb free expression, and protestors often face excessive force and the use of abusive weapons such as pellet-firing shotguns. While the region seemed to have slowly emerging out of the complete crackdown imposed on 5 August 2019, with the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the lockdown was reimposed and so the conditions for civilians remain dire. -

Socio-Economic Status of Fishermen in District Srinagar of Jammu and Kashmir

IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences ISSN 2455-2267; Vol.05, Issue 01 (2016) Pg. no. 66-70 Institute of Research Advances http://research-advances.org/index.php/RAJMSS Socio-economic status of fishermen in district Srinagar of Jammu and Kashmir 1 Nasir Husain, 2 M.H. Balkhi, 3 T.H. Bhat and 4 Shabir A. Dar 1,2,3,4 Faculty of Fisheries, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences & Technology of Kashmir, Rangil, Ganderbal – 190 006, J&K, India. Type of Review: Peer Reviewed. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v5.n1.p8 How to cite this paper: Husain, N., Balkhi, M., Bhat, T., & Dar, S. (2016). Socio-economic status of fishermen in district Srinagar of Jammu and Kashmir. IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences (ISSN 2455-2267), 5(1), 66-70. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v5.n1.p8 © Institute of Research Advances This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License subject to proper citation to the publication source of the work. Disclaimer: The scholarly papers as reviewed and published by the Institute of Research Advances (IRA) are the views and opinions of their respective authors and are not the views or opinions of the IRA. The IRA disclaims of any harm or loss caused due to the published content to any party. 66 IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences ABSTRACT A Socio-economic status of fishermen living on the banks of River Jhelum, Dal Lake and Anchar Lake was investigated in district Srinagar of Jammu and Kashmir. -

OFFICE of the CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER DODA Tentative Seniority List of Junior Assistants in Respect of District Doda…

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER DODA Tentative Seniority list of Junior Assistants in respect of District Doda… Date of First DATE FROM QUALI- WHICH WORKING S-NO Zone NAME OF OFFICIALS SEX PLACE OF POSTING D-O-B appointment RESEIDENCE CATEGORY REMAKRS FICATION IN THE as Jr- Asstt INSTITUTION 1 Thathri Nisar Ahmed Male HSS Jangalwar 12th 13-02-1974 23-05-2009 19-05-2016 Phagsoo RBA 2 Doda Shaishta Kouser Female DIET Doda BSc, DCA 26-05-1974 01-04-2010 24-04-2010 Doda Gen 3 Bhaderwah Abida Begum Female HSS Boys Bhaderwah 10+2 02-10-1966 20-03-2014 28-05-2018 Bhaderwah Gen 4 Doda Imtiaz Hussain Male ZEO Office Doda BA 24-10-1974 30-05-2014 30-05-2014 Shinal Doda Gen 5 Bhaderwah Archana Kotwal Female HSS Boys Bhaderwah MSc IT 20-04-1984 30-05-2014 30-05-2014 Udrana Gen 6 Doda Sajad Hussain Male DIET Doda B-A- 06-07-1985 30-05-2014 30-05-2014 Doda Gen 7 Bhagwah Vikram singh Male ZEO Office Bhagwah Matric 18-09-1971 20-06-2014 20-06-2014 Gadi RBA Promoted through 8 Doda Taib Hussain Male HSS Sazan 12th 11-10-1991 16-08-2014 16-08-2014 Sazan RBA Hon'ble Court 9 Gundna Ved Perkash Male HS Barshalla 10th 01-07-1965 21-08-2014 10-08-2016 Thathri SC 10 Doda Farooq Ahmed Male HSS Boys Doda 12TH 07-02-1968 21-08-2014 04-06-2018 Doudhte Gen 11 Bhaderwah Zakir Hussain Male HS Manthala 12th 06-08-1971 22-08-2014 05-06-2017 Banoon Bonjwah Gen 12 Thathri Daya Krishan Male HSS Bhella B-A- 25-03-1972 21-08-2014 29-05-2018 Shaja RBA 13 Thathri Javeed Ahmed Male ZEO Office Thathri 10th 15-08-1972 22-08-2014 Aug-16 Thathri Gen 14 Assar Imtyaz Ahmed Male -

The Occupied Clinic Militarism and Care in Kashmir / Saiba Varma the OCCUPIED CLINIC the Occupied Clinic

The Occupied Clinic Militarism and Care in Kashmir / Saiba Varma THE OCCUPIED CLINIC The Occupied Clinic Militarism and Care in Kashmir • SAIBA VARMA DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Text design by Amy Ruth Buchanan Cover design by Courtney Leigh Richardson Typeset in Portrait by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Varma, Saiba, [date] author. Title: The occupied clinic : militarism and care in Kashmir / Saiba Varma. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019058232 (print) | lccn 2019058233 (ebook) isbn 9781478009924 (hardcover) isbn 9781478010982 (paperback) isbn 9781478012511 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Psychiatric clinics—India—Jammu and Kashmir. | War victims—Mental health—India—Jammu and Kashmir. | War victims—Mental health services— India—Jammu and Kashmir. | Civil-military relations— India—Jammu and Kashmir. | Military occupation— Psychological aspects. Classification:lcc rc451.i42 j36 2020 (print) | lcc rc451.i42 (ebook) | ddc 362.2/109546—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019058232 isbn ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019058233 Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the Office of Vice Chancellor for Research at the University of California, San Diego, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Cover art: Untitled, from The Depth of a Scar series. © Faisal Magray. Courtesy of the artist. For Nani, who always knew how to put the world back together CONTENTS MAP viii NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi LETTER TO NO ONE xv INTRODUCTION. Care 1 CHAPTER 1. -

Pahalgam –Jammu & Kashmir

PAHALGAM –JAMMU & KASHMIR VISIT OF HON’BLE VICE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, SHRI MOHD HAMID ANSARI ON 15 SEP 2012 TO JIM & WS 1 HON’BLE VICE PRESIDENT’S VISIT TO JAWAHAR INSTITUTE OF MOUNTAINEERING & WINTER SPORTS, PAHALGAM – J&K GENERAL Jawahar Institute of mountaineering & Winter Sports is a joint venture between Ministry of Defence, GOI and Deptt. Of Tourism Govt. of J&K. it is located at Pahalgam and sub training centers at Sanasar, Bhaderwah and Shey (Leh). The Institute has excelled in various mountaineering activities and adventure sports over last 29 years. Hon’ble Defence Minister GOI and Hon’ble Chief Minister Jammu & Kashmir are President and Vice President of the Institute respectively. HQ JIM & WS PAHALGAM AIM To visit the Institute and to experience and observe the adventure activities carried out by JIM & WS, Pahalgam. 2 APPROVED SCHEDULE PROGRAMME CARRIED OUT BY JIM & WS FOR THE VISIT OF HON’BLE VICE PRESIDENT SHRI MOHD HAMID ANSARI INTRODUCTION TO JIM & WS STAFF, INSTRUCTORS AND TRAINEES 1. The Principal of JIM&WS welcome and receive the Honb’le Vice President of India Shri Mohd Hamid Ansari along with His Excellency Shri NN Vohra, Governor of Jammu & Kashmir and presented a bouquet and then introduced with staff of the institute and members of Mount Golup Kangri expedition were happy to interact with the Hon’ble Vice President of India. WELCOMING AND PRESENTING BOUQUET 3 INTRODUCTION TO MOUNTAINEERING EQUIPMENT 2. Havildar Instructor Hazari Lal introduced the Hon’ble Vice President of India with various mountaineering specialized equipment used during adventure activities like mountaineering, water rafting, paragliding. -

Development Udaan's Flight and Feedback

Thought of the month: Culture You can never cross the ocean until Glimpse of Gojri folk music in J & K you have the courage to lose sight of shore. Christopher Columbus From Editors desk Jammu and Kashmir update is a unique initiative of Ministry of Home Affairs to showcase the positive developments taking place in the state, The ambit of the magazine covers all the three regions of the The Gujjar tribes in J&K, mostly in Poonch and Rajouri districts state with focus on achievements of of Jammu division and in other districts of Kashmir valley, play the people. musical instruments which are part of their nomadic practice. In To make it participatory, the their musical practices they have their unique traditions. They magazine invites success stories/ hold distinct composition and tunes, which separate the Gojri unique achievements, along with music from Kashmiri, Dogri and Punjabi music in the state.The tradition of music and singing has been continuing for long photographs in the field of sports, among the Gujjars of the state. adventure sports, studies, business, art, culture, positive welfare The main folk instruments used by Gujjars are mainly made initiatives, social change, religious from wood, animal skin, clay metal or other material. Their main harmony, education including musical instrument is called Banjli or flute. pieces of art like drawings, cartoons, On occasions of festivity, marriages and Melas, singers and poems, short stories (not more than flute players are generally asked by elders to display their skills, 150 words) or jokes on post Box while ‘bait bazi’ (reciting poetry) continues for hours. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region August 2008 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN MERRITT ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Brevard and Volusia Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia August 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 3 U.S. Fish And Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 4 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 4 Legal Policy Context ..................................................................................................................... 5 National Conservation Plans and Initiatives .................................................................................6 Relationship to State Partners ..................................................................................................... -

Detailed Results

Election Commission of India- State Election, 2008 to the Legislative Assembly Of Jammu & Kashmir DETAILED RESULTS VALID VOTES POLLED % VOTES CAND SL. CANDIDATE NAME SEX AGE CATEGORY PARTY GENERAL POSTAL TOTAL POLLED as per form 7 Constituency 1. Karnah TOTAL ELECTORS : 26941 11 1 KAFIL UR REHMAN M 53 GEN JKN 4110 0 4110 19.15 9 2 AB REHMAN BHADANA M 66 ST JKANC 2961 1 2962 13.80 2 3 JAVID AHMAD MIRCHAL M 30 GEN SDP 2911 0 2911 13.57 10 4 ALI ASGAR KHAN M 69 GEN IND 2642 0 2642 12.31 4 5 RAJA MANZOOR AHMAD M 53 GEN JKPDP 2616 0 2616 12.19 KHAN 6 6 SYED YASIN SHAH M 60 GEN INC 2245 0 2245 10.46 13 7 MOHD ABASS M 57 GEN IND 1708 0 1708 7.96 14 8 MOHD NASEEM M 48 GEN IND 770 0 770 3.59 8 9 ZIYAFAT LONE M 28 GEN IND 484 0 484 2.26 7 10 SHAHNAZ AHMAD M 34 GEN IND 295 0 295 1.37 1 11 TAJA PARVEEN F 67 GEN JKPDF 226 0 226 1.05 3 12 JEHANGIR KHAN M 33 GEN JKNPP 182 0 182 0.85 12 13 LAL DIN PLOUT M 45 GEN SP 174 0 174 0.81 5 14 SAIYDA BAGUM F 38 GEN BSP 133 0 133 0.62 TOTAL: 21457 1 21458 79.65 Turn Out Constituency 2. Kupwara TOTAL ELECTORS : 88942 18 1 MIR SAIFULLAH M 48 GEN JKN 16673 23 16696 30.07 12 2 FAYAZ AHMAD MIR M 31 GEN JKPDP 11510 4 11514 20.74 7 3 SHABNAM GANI LONE F 44 GEN IND 11047 3 11050 19.90 10 4 ABDUL MAJEED KHAN M 58 GEN IND 2673 0 2673 4.81 8 5 ABDUL AHAD MIR M 38 GEN PDF 2495 0 2495 4.49 11 6 ABDUL MAJEED SHEIKH M 44 GEN IND 2232 5 2237 4.03 3 7 CHOWDRY SALAM - UD -DIN M 58 GEN INC 2046 0 2046 3.68 2 8 SONAULLA BHAT M 40 GEN IND 814 0 814 1.47 19 9 NAZIR AHMAD KHAN M 48 GEN BJP 758 1 759 1.37 9 10 ABDUL REHMAN LONE M 43