Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolv Ryssdal* President, and the Former Vice-President, Hermann Mosler Council of Europe

section Some Notable People3 in the Court’s History CHAPTER 7 Presidents of the Court Lord (Arnold Duncan) McNair (1885–1975) British • Barrister, law professor and international judge • Judge (1946–52) and President of the International Court of Justice (1952–5) • President (1959–65) and thereafter judge at the Court (1965–6) Lord McNair served as the first President of the Court. He was educated at Aldenham School and Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, where he read law. From 1907 to 1908 he was Secretary of the Cambridge University Liberal Club, and in 1909 he was President of the Cambridge Union. After practising as a solicitor in London, he returned to Cambridge in 1912 to become a fellow of his old college, later becoming senior tutor. In 1917 he was called to the Bar, Gray’s Inn. He had taken an interest in international law from an early age, and in 1935 he was appointed Whewell Professor of International Law at Cambridge. However, he left this chair in 1937 to become Vice-Chancellor of Above: Lord (Arnold Duncan) McNair. Liverpool University. He remained at Liverpool until 1945, Opposite: Poster with some of the when he returned to Cambridge to take up the position of Convention’s keywords (2009). Professor of Comparative Law. The following year he was 106 The Conscience of Europe: 50 Years of the European Court of Human Rights Chapter 7: Presidents of the Court elected a judge of the International Court of Justice in The rights. He wanted above all to place human rights at the heart 1974 that France ratified the Convention, only two years Hague, a post he held until 1955, and he was also President of the European construction project then just beginning. -

Volume.1, Issue.1 AVE MARIA INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL

AVE MARIA INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL SYMPOSIUM: THE HOLY SEE: INTERNATIONAL PERSON AND SOVEREIGN ARTICLES The Holy See: International Person and Sovereign Robert John Araujo Foreign Sovereign Immunity and the Holy See Robert John Araujo The New Delicta Graviora Laws Davide Cito Le nuove norme sui delicta graviora Davide Cito The Holy See in Dialogue With the Jane Adolphe Committee on the Rights of the Child STUDENT NOTE The Truth Unraveled: Lowering Maternal Mortality Elise Kenny Inaugural Issue Volume 1 Fall 2011 Dedicated to Robert John Araujo, S.J. AVE MARIA INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL 2011 - 2012 EDITORIAL BOARD ISSN 2375-2173 JESSICA HOYT Editor-in-Chief CHANILLE L. GRIGSBY ELISE KENNY Managing Editor Publication Manager MAJEL BRADEN MATEUSZ SZYMANSKI Executive Articles Editor Executive Articles Editor SENIOR EDITORS MELINDA ALICO AMY PENFOLD GENEVIEVE TURNER ASSOCIATE EDITORS MICHAEL ACQUILANO ASHLEY HARVEY MUKENI NADINE NTUMBA ASTHA ADHIKARY MARKUS HORNER ALISON ROGERS DOUGLAS CHRISTIANSEN BRENDAN MURPHY MARISSA ROZAS CATHERINE DREYER STEPHANIE MUSKUS COREY SMITH BRIAN GRAVUNDER RENEE VEZINA FACULTY ADVISORS JUDGE DANIEL RYAN PROFESSOR JANE ADOLPHE PROFESSOR KEVIN GOVERN AVE MARIA INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL 2010 - 2011 EDITORIAL BOARD CHERYL LEDOUX Editor-in-Chief STEPHANIE GREWE JENNA ROWAN Managing Editor Publication Manager KATHERINE BUDZ SARA SCHMELING Executive Articles Editor Executive Articles Editor SENIOR EDITORS DOUG LAING LISA UTTER ASSOCIATE EDITORS MELINDA ALICO CHANILLE GRIGSBY AMY PENFOLD MAJEL BRADEN JESSICA HOYT MATEUSZ SZYMANSKI EVA-MARIE CHITTY ELISE KENNY GENEVIEVE TURNER FACULTY ADVISORS JUDGE DANIEL RYAN PROFESSOR JANE ADOLPHE ARTICLE SUBMISSIONS The Ave Maria International Law Journal is constantly seeking timely and thought- provoking articles that engage the international legal community on a wide range of topics. -

Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law

Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law Publication TheCambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law (CJICL) is an open-access publication available online at <http://cilj.co.uk>. Each volume consists of two or more general issues and occasional symposiums on a particular area of law. Editorial policy All submissions are subject to a double-blind peer-review editorial process by our Academic Review Board and/or our Editorial Board. Submissions The Journal accepts the following types of manuscript: (i) Long Articles between 6,000 and 12,000 words but not exceeding 12,000 words including footnotes; (ii) Short Articles not exceeding 5,000 words including footnotes; (iii) Case Notes not exceeding 3,000 words including footnotes; and (iv) Book Reviews not exceeding 2,500 words including footnotes. Please visit our website for submission details. Copyright and open-access policy The CJICL is an open-access publication governed by our publishing and licensing agreement. Any commercial use and any form of republication of material not covered by the applicable license is subject to the express permission of the Editors-in-Chief. Contact information Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law Faculty of Law, 10 West Road Cambridge, CB3 9DZ United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://cilj.co.uk Typeset in InDesign. ISSN 2050–1706 (Print) ISSN 2050–1714 (Online) © 2016 Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law and Contributors This issue should be cited as (2016) 5(3) CJICL. http://cilj.co.uk -

The International Court of Justice and the 'Principle Of

CHAPTER 25 THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE AND THE ‘PRINCIPLE OF NON-USE OF FORCE’ CLAUS KREß I. Introduction The international law on the use of force underwent signifcant developments in the inter-war period, most signifcantly through the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy, as enshrined in Article I of the 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact.1 Yet, the law preceding the United Nations Charter2 remained fraught with uncertainties due, perhaps most importantly, to the notoriously ambiguous concept of war and the possible scope for certain lawful forcible measures short of war.3 Te 1 General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy of 27 Aug 1928, LNTS XCIV (1929), 58. 2 Charter of the United Nations and Statute of the International Court of Justice, 26 June 1945. 3 For one important exposition of the complexities of the pre-Charter law on the use of force, see Ian Brownlie, International Law and the Use of Force by States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963), 19–111, 214–50; Sir Humphrey Waldock, ‘Te Regulation of the Use of Force by Individual States in International Law’ (1952-II) 81 Receuil des cours de l’Académie de droit international 455. Weller180414OUK.indb 561 12/18/2014 7:26:34 PM 562 CLAUS KREß Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) had not developed a case law on those matters4 and only limited light was shed on them by the International Military Tribunals immediately afer the Second World War.5 Since 1945, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has been called upon to interpret the UN Charter provisions on the use of force in international relations against this international law back- ground full of obscurities. -

Brierly's Law of Nations

BRIERLY’S LAW OF NATIONS This page intentionally left blank BRIERLY’S LAW OF NATIONS An Introduction to the Role of International Law in International Relations SEVENTH EDITION A NDREW C LAPHAM 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Andrew Clapham 2012 Th e moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2012 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Crown copyright material is reproduced under Class Licence Number C01P0000148 with the permission of OPSI and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN 978–0–19–965793–3 978–0–19–965794–0 (pbk) Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

The Status of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in National and International Law

THE STATUS OF THE UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LAW Hurst Hannum* CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 289 I. THE UNIVERSAL DECLARATION IN NATIONAL LAW .......... 292 A. Reference to the Universal Declaration in National Courts .................................. 292 1. The Universal DeclarationAs a Rule of Deci- sion ............................. 296 2. The Universal DeclarationAs an Aid to Consti- tutional or Statutory Interpretation ........ 298 3. Judicial Rejection of the Universal Declaration As Relevant to Interpretationsof Domestic Law ............................. 311 B. Influence of the Universal Declaration on Legislative and Administrative Acts ..................... 312 IlI. STATUS OF THE UNIVERSAL DECLARATION IN CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW .......... 317 A. Views of the InternationalCourt of Justice ........... 335 B. The Content of Customary Law Evidenced in the Decla- ration .................................. 340 * Associate Professor of International Law, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. This article is based on a report prepared by the author as Rapporteur of the Committee on the Enforcement of International Human Rights Law of the International Law Association. The author would like to thank Richard B. Lillich, Chairman of the Committee; current or former Committee members Andrew Byrnes, Subrata Roy Chowdhury, Emmanuel Decaux, John Dugard, Kshama Femando, Jan Helgesen, Matthias Herdegen, Christof H. Heyns, John P. Humphrey, Menno T. Kamminga, Vladimir A. Kartashkin, Mathias-Charles Krafft, Anthony P. Lester, Dennis Mahoney, Momir Milojevic, Matti PellonpM, Rodney N. Purvis, Voitto Saario, Dhruba B. S. Thapa, Antonio A. Cangado Trindade, Raul Vinuesa, and Mandigui V. Yokabdjim; and Research Assistants Jennifer Gergen, Laura Gil, Kingsley Moghalu, and Jean-Louis Robadey for their comments and assistance in gathering often difficult-to-find information. -

Domestic Courts and the Interpretation of International Law Developments in International Law

Domestic Courts and the Interpretation of International Law Developments in International Law volume 72 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ diil Domestic Courts and the Interpretation of International Law Methods and Reasoning Based on the Swiss Example By Odile Ammann LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC- BY- NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Faculty of Law of the University of Fribourg (Switzerland) does not intend to approve or disapprove the opinions expressed in a dissertation; they must be considered as the author’s own (decision of the Faculty Council of 1 July 1916). Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. Cover illustration: Lady Justice sorting methodically through the Swiss case law on international law. © 2019 Rae Pozdro. All rights reserved. www.pozdro.net The Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available online at http:// catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http:// lccn.loc.gov/2019948876 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill- typeface. issn 0924- 5332 isbn 978- 90- 04- 40986- 6 (hardback) isbn 978- 90- 04- 40987- 3 (e- book) Copyright 2020 by Odile Ammann. Published by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. -

Imagereal Capture

[1991] AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL LAW NEWS No. 91/2 7 February 1991 Judge Sir Robert Yewdall Jennings is elected President of the International Court of Justice Judge Shigeru Oda is elected Vice-President The following information is communicated to the Press by the Registry of the International Court of Justices Today, 7 February 1991, the International Court of Justice elected Judge Sir Robert Yewdall Jennings to be its President and Judge Shigeru Oda to be its Vice-President. Their terms of office as President and Vice-President will come to an end in 1994. Their membership of the Court is due to expire in 2000 and 1994 respectively. Biographies of the new President and Vice-President are attached to this communique. The composition of the Court is now as follows: President Sir Robert Yewdall Jennings (United Kingdom) Vice-President Shigeru Oda (Japan) Judges Manfred Lachs (Poland) Taslim Olawale Elias (Nigeria) Roberto Ago (Italy) Stephen M. Schwebel (United States of America) Mohammed Bedjaoui (Algeria) Ni Zheng3m (China) Jens Evensen (Norway) Nikolai K. Tarassov (USSR) Gilbert Guillaume (France) Mohamed Shahabuddeen (Guyana) Andres Aguilar Mawdsley (Venezuela) Christopher G. Weeramantry (Sri Lanka) Raymond Ranjeva (Madagascar) PCdll 206 [1991] AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL LAW NEWS Judge Sir Robert Yewdall Jennings (Member of the Court since 6 February 1982) Born on 19 October 1913. Studied at Cambridge University, obtaining the degrees of M.A. and LL.B., and subsequently at Harvard University (Choate Fellow, 1936 1937). Honorary Doctor of Law, Universities of Hull (1987) and of Saarland (1988). Assistant Lecturer in Law, London School of Economics (1938-1939). Lecturer (1946-1955) and subsequently Whewell Professor of International Law in the University of Cambridge (1955-1982). -

Academy of European Law Twenty-Seventh Session

Academy of European Law Twenty-seventh Session Human Rights Law 20 June – 1 July 2016 Reading Materials The European Court of Human Rights as a Source of Human Rights Law Ineta Ziemele Professor, Riga Graduate School of Law; Judge of the Constitutional Court of Latvia; former judge and Section President at the European Court of Human Rights TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 Course Outline 1 2 Reading List 3 3 Harris, O’Boyle & Warbrick, Law of the European Convention on 5 Human Rights, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2014 4 Luzius Wildhaber, Arnaldur Hjartarson, Stephen Donnelly, “No 24 Consensus on Consensus? The Practice of the European Court of Human Rights”, Human Rights Law Journal, Vol. 33, No. 7-12 (2013). 5 Steven Greer, The European Convention on Human Rights. 40 Achievements, Problems and Prospects, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 316 – 321. 6 Ineta Ziemele, “International Courts and Ultra Vires Acts”, in 46 Caflisch et al (eds.), Liber Amicorum Luzius Wildhaber. Human Rights – Strasbourg Views.Droits de l’Homme – Regards de Strasbourg. N.P.Engel, Publisher, 2007, pp. 537 – 556 7 James Crawford, Chance, Order, Change: The Course of 66 International Law, Hague Academy of International Law, 2016, Chapter IX. The European Court of Human Rights as a Source of Human Rights Law Professor Ineta Ziemele Ph.D. (Cantab.) Judge of the Constitutional Court of Latvia, former judge and Section President at the European Court of Human Rights Outline of the lectures: 1. Introduction – setting the stage - Article 38. 1 (d) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice: “judicial decisions as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law” - Article 32 of the ECHR: “1. -

Scholarly Writings As a Source Of

Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law Publication Copyright and open-access policy The Cambridge Journal of International The CJICL is an open-access publication gov- and Comparative Law is an open- erned by our publishing and licensing agree- access publication available online at ment. Any commercial use and any form of <http://www.cjicl.org.uk>. Hardcopies can republication of material in the Journal is sub- be ordered on request. Each volume consists of two or more main issues and a special is- ject to the express permission of the Editors sue examining the jurisprudence of the UK in Chief. Supreme Court. Contact information Editorial Policy Cambridge Journal of International and Com- All submissions are subject to a double-blind parative Law peer-review editorial process by our Aca- Faculty of law, 10 West Road demic Review Board and/or our Editorial Team. Cambridge, CB3 9DZ United Kingdom Submissions The journal accepts the following types of E-mail: [email protected] manuscript: Web: http://www.cjicl.org.uk (i) Long Articles between 6,000 and 10,000 words but not exceeding 10,000 words in- Typeset in Crimson and Gentium Book Basic, cluding footnotes; distributed under the terms of the SIL Open Font (ii) Short Articles not exceeding 5,000 words including footnotes; license, available at <http://scripts.sil.org/OFL>. (iii) Case Notes not exceeding 3000 words in- cluding footnotes; and (iv) Book Reviews not exceeding 2500 words including footnotes. Please visit our website for submission dead- lines. ISSN 2050-1706 (Print) ISSN 2050-1714 (Online) © 2012 Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law and Contributors This volume should be cited as (2012) 1(3) C.J.I.C.L. -

(CLP) Lecture Whither the Margin of Appreciation?

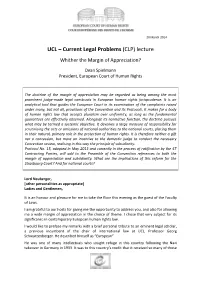

20 March 2014 UCL – Current Legal Problems (CLP) lecture Whither the Margin of Appreciation? Dean Spielmann President, European Court of Human Rights The doctrine of the margin of appreciation may be regarded as being among the most prominent judge-made legal constructs in European human rights jurisprudence. It is an analytical tool that guides the European Court in its examination of the complaints raised under many, but not all, provisions of the Convention and its Protocols. It makes for a body of human rights law that accepts pluralism over uniformity, as long as the fundamental guarantees are effectively observed. Alongside its normative function, the doctrine pursues what may be termed a systemic objective. It devolves a large measure of responsibility for scrutinising the acts or omissions of national authorities to the national courts, placing them in their natural, primary role in the protection of human rights. It is therefore neither a gift nor a concession, but more an incentive to the domestic judge to conduct the necessary Convention review, realising in this way the principle of subsidiarity. Protocol No. 15, adopted in May 2013 and currently in the process of ratification by the 47 Contracting Parties, will add to the Preamble of the Convention references to both the margin of appreciation and subsidiarity. What are the implications of this reform for the Strasbourg Court? And for national courts? Lord Neuberger, [other personalities as appropriate] Ladies and Gentlemen, It is an honour and pleasure for me to take the floor this evening as the guest of the Faculty of Laws. I am grateful to our hosts for giving me the opportunity to address you, and also for allowing me a wide margin of appreciation in the choice of theme. -

University of Southampton Faculty of Business, Law and Art Southampton Law School Volume 1 of 1 the European Convention on Human

University of Southampton Faculty of Business, Law and Art Southampton Law School Volume 1 of 1 The European Convention on Human Rights and the Living Instrument Doctrine: An Investigation into the Convention’s Constitutional Nature and Evolutive Interpretation By Thomas Webber Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 1 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF BUSINESS, LAW AND ARTS Doctor of Philosophy The European Convention on Human Rights and the Living Instrument Doctrine: An Investigation into the Convention’s Constitutional Nature and Evolutive Interpretation By Thomas Webber Currently mired in controversy, the European Court of Human Rights and the Convention itself have come in for stern criticism from a diverse array of stakeholders. Of particular controversy is the Court’s utilisation of the Living instrument doctrine, which it first expressly recalled in its 1978 Tyrer v. UK decision. Confusion has continued to surround how this doctrine came about and its potential to allow the Strasbourg Judiciary to cross over the constitutional separation of judiciary and legislature. However, while the substantive idea of the Convention as a living instrument capable of evolving with European Society is legitimate, confusion still exists about how it operates and to what extent it might be used to alter existing Convention Standards. This study sets out that at the heart of this modern legitimacy crisis in the Convention system is a failed dialogical model of the Convention institutions. However, clearer explanations and a better understanding of appropriate roles of the various institutions and improved channels of dialogue may lead to a more accepted Convention system and act to calm some of the conflict surrounding the Convention today.