Papers on the North American Fur Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cumulative Index North Dakota Historical Quarterly Volumes 1-11 1926 - 1944

CUMULATIVE INDEX NORTH DAKOTA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY VOLUMES 1-11 1926 - 1944 A Aiton, Arthur S., review by, 6:245 Alaska, purchase of, 6:6, 7, 15 A’Rafting on the Mississipp’ (Russell), rev. of, 3:220- 222 Albanel, Father Charles, 5:200 A-wach-ha-wa village, of the Hidatsas, 2:5, 6 Albert Lea, Minn., 1.3:25 Abandonment of the military posts, question of, Albrecht, Fred, 2:143 5:248, 249 Alderman, John, 1.1:72 Abbey Lake, 1.3:38 Aldrich, Bess Streeter, rev. of, 3:152-153; Richard, Abbott, Johnston, rev. of, 3:218-219; Lawrence, speaker, 1.1:52 speaker, 1.1:50 Aldrich, Vernice M., articles by, 1.1:49-54, 1.4:41- Abe Collins Ranch, 8:298 45; 2:30-52, 217-219; reviews by, 1.1:69-70, Abell, E. R, 2:109, 111, 113; 3:176; 9:74 1.1:70-71, 1.2:76-77, 1.2:77, 1.3:78, 1.3:78-79, Abercrombie, N.Dak., 1.3: 34, 39; 1.4:6, 7, 71; 2:54, 1.3:79, 1.3:80, 1.4:77, 1.4:77-78; 2:230, 230- 106, 251, 255; 3:173 231, 231, 231-232, 232-233, 274; 3:77, 150, Abercrombie State Park, 4:57 150-151, 151-152, 152, 152-153, 220-222, 223, Aberdeen, D.T., 1.3:57, 4:94, 96 223-224; 4:66, 66-67, 67, 148, 200, 200, 201, Abraham Lincoln, the Prairie Years (Sandburg), rev. of, 201, 202, 202, 274, 275, 275-276, 276, 277-278; 1.2:77 8:220-221; 10:208; 11:221, 221-222 Abstracts in History from Dissertations for the Degree of Alexander, Dr. -

A New Look at the Himalayan Fur Trade

ORYX VOL 27 NO 4 OCTOBER 1993 A new look at the Himalayan fur trade Joel T. Heinen and Blair Leisure In late December 1991 and January 1992 the authors surveyed tourist shops sell- ing fur and other animal products in Kathmandu, Nepal. Comparing the results with a study conducted 3 years earlier showed that the number of shops had in- creased, but indirect evidence suggested that the demand for their products may have decreased. There was still substantial trade in furs, most of which appeared to have come from India, including furs from species that are protected in India and Nepal. While both Nepali and Indian conservation legislation are adequate to con- trol the illegal wildlife trade, there are problems in implementation: co-ordination between the two countries, as well as greater law enforcement within each country, are needed. Introduction Enforcement of conservation legislation Since the 1970s Nepal and India have been In spite of measurable successes with regard considered to be among the most progressive to wildlife conservation, there are several ob- of developing nations with regard to legis- stacles to effective law enforcement in both lation and implementation of wildlife conser- countries. In Nepal the Department of vation programmes. The Wildlife (Protection) National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act of India was passed in 1972 (Saharia and (DNPWC), which is the designated manage- Pillai, 1982; Majupuria 1990a), and Nepal's ment authority of CITES (Fitzgerald, 1989; National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act Favre, 1991), is administratively separate from was passed in 1973 (HMG, 1977). Both have the Department of Forestry, but both depart- schedules of fully protected species, including ments are within the Ministry of Forests and many large mammalian carnivores and other the Environment. -

The Fur Trade of the Western Great Lakes Region

THE FUR TRADE OF THE WESTERN GREAT LAKES REGION IN 1685 THE BARON DE LAHONTAN wrote that ^^ Canada subsists only upon the Trade of Skins or Furrs, three fourths of which come from the People that live round the great Lakes." ^ Long before tbe little French colony on tbe St. Lawrence outgrew Its swaddling clothes the savage tribes men came in their canoes, bringing with them the wealth of the western forests. In the Ohio Valley the British fur trade rested upon the efficacy of the pack horse; by the use of canoes on the lakes and river systems of the West, the red men delivered to New France furs from a country unknown to the French. At first the furs were brought to Quebec; then Montreal was founded, and each summer a great fair was held there by order of the king over the water. Great flotillas of western Indians arrived to trade with the Europeans. A similar fair was held at Three Rivers for the northern Algonquian tribes. The inhabitants of Canada constantly were forming new settlements on the river above Montreal, says Parkman, ... in order to intercept the Indians on their way down, drench them with brandy, and get their furs from them at low rates in ad vance of the fair. Such settlements were forbidden, but not pre vented. The audacious " squatter" defied edict and ordinance and the fury of drunken savages, and boldly planted himself in the path of the descending trade. Nor is this a matter of surprise; for he was usually the secret agent of some high colonial officer.^ Upon arrival in Montreal, all furs were sold to the com pany or group of men holding the monopoly of the fur trade from the king of France. -

Status of Mineral Resource Information for the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, North Dakota

STATUS OF MINERAL RESOURCE INFORMATION FOR THE FORT BERTHOLD INDIAN RESERVATION, NORTH DAKOTA By Bradford B. Williams Mary E. Bluemle U.S. Bureau of Mines N. Dak. Geological Survey Administrative report BIA-40 1978 CONTENTS SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................ 1 Area Location and Access .................................................... 1 Past Investigations .......................................................... 2 Present Study and Acknowledgments ........................................... 2 Land Status................................................................ 2 Physiography .............................................................. 3 GEOLOGY ..................................................................... 4 Stratigraphy ............................................................... 4 Subsurface .......................................................... 4 Surface ............................................................. 4 General ....................................................... 4 Bullion Creek and Sentinel Butte Formations ......................... 8 Golden Valley Formation......................................... 9 Cole Harbor Formation .......................................... 9 Structure................................................................. 10 MINERAL RESOURCES ......................................................... 11 General ................................................................. -

NWC-3361 Cover Layout2.Qx

2 0 0 1 A N N U A L R E P O R T vision growth value N O R T H W E S T C O M P A N Y F U N D 2 0 0 1 A N N U A L R E P O R T 2001 financial highlights in thousands of Canadian dollars 2001 2000 1999 Fiscal Year 52 weeks 52 weeks 52 weeks Results for the Year Sales and other revenue $ 704,043 $ 659,032 $ 626,469 Trading profit (earnings before interest, income taxes and amortization) 70,535 63,886 59,956 Earnings 29,015 28,134 27,957 Pre-tax cash flow 56,957 48,844 46,747 Financial Position Total assets $ 432,033 $ 415,965 $ 387,537 Total debt 151,581 175,792 171,475 Total equity 219,524 190,973 169,905 Per Unit ($) Earnings for the year $ 1.95 $ 1.89 $ 1.86 Pre-tax cash flow 3.82 3.28 3.12 Cash distributions paid during the year 1.455 1.44 1.44 Equity 13.61 13.00 11.33 Market price – January 31 17.20 13.00 12.00 – high 17.50 13.00 15.95 – low 12.75 9.80 11.25 Financial Ratios Debt to equity 0.69:1 0.92:1 1.01:1 Return on net assets* 12.7% 11.5% 11.6% Return on average equity 14.9% 15.2% 16.8% *Earnings before interest and income taxes as a percent of average net assets employed All currency figures in this report are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise noted. -

George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West Mitchell Edward Pike Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West Mitchell Edward Pike Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Pike, Mitchell Edward, "George Drouillard and John Colter: Heroes of the American West" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 444. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/444 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE GEORGE DROUILLARD AND JOHN COLTER: HEROES OF THE AMERICAN WEST SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR LILY GEISMER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY MITCHELL EDWARD PIKE FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING/2012 APRIL 23, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..4 Chapter One. George Drouillard, Interpreter and Hunter………………………………..11 Chapter Two. John Colter, Trailblazer of the Fur Trade………………………………...28 Chapter 3. Problems with Second and Firsthand Histories……………………………....44 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….……55 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..58 Introduction The United States underwent a dramatic territorial change during the early part of the nineteenth century, paving the way for rapid exploration and expansion of the American West. On April 30, 1803 France and the United States signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty, causing the Louisiana Territory to transfer from French to United States control for the price of fifteen million dollars.1 The territorial acquisition was agreed upon by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Republic of France, and Robert R. Livingston and James Monroe, both of whom were acting on behalf of the United States. Monroe and Livingston only negotiated for New Orleans and the mouth of the Mississippi, but Napoleon in regard to the territory said “I renounce Louisiana. -

Fur Trade & Beaver Ecology

Oregon’s First Resource Industry: The Fur Trade & Beaver Ecology in the Beaver State Grades: Versions for 4-HS Subjects: American History, Oregon History, Economics, Social Studies Suggested Time Allotment: 1-2 Class Periods Background: The first of Oregon’s natural resources to be recognized and extracted by Euro-Americans was fur. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, furs were highly valuable commodities of international trade. Early explorers of the northwest, such as Robert Gray and Lewis and Clark, reported that the region’s many waterways supported an abundant population of sea otter and beaver. When people back east heard about this, they knew that there was the potential of great profits to be made. So, the first permanent Euro-American settlements in Oregon were trading outposts established by large and powerful fur trading companies that were based in London and New York. Initially the traders in Oregon obtained their furs by bartering with Native Americans. As the enormous value of the northwest’s fur resources quickly became apparent to them, corporations such as Hudson’s Bay Company and Pacific Fur Company decided to start employing their own workforce, and professional trappers were brought in from Canada, the American states, and islands of the South Seas. The increasing number of trappers and competition between English and American companies quickly began to deplete the populations of the fur-bearing animals. In fact, by 1824 the Hudson’s Bay Company was pursuing a strategy of intentionally ‘trapping out’ and eliminating beaver from entire sections of the Oregon interior in order to keep rival businesses from moving into those areas. -

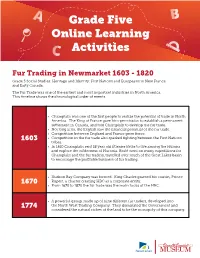

Grade Five Online Learning Activities

Grade Five Online Learning Activities Fur Trading in Newmarket 1603 - 1820 Grade 5 Social Studies: Heritage and Identity: First Nations and Europeans in New France and Early Canada. The Fur Trade was one of the earliest and most important industries in North America. This timeline shows the chronological order of events. • Champlain was one of the first people to realize the potential of trade in North America. The King of France gave him permission to establish a permanent settlement in Canada, and told Champlain to develop the fur trade. • Not long after, the English saw the financial potential of the fur trade. • Competition between England and France grew fierce. 1603 • Competition in the fur trade also sparked fighting between the First Nations tribes. • In 1610 Champlain sent 18 year old Étienne Brulé to live among the Hurons and explore the wilderness of Huronia. Brulé went on many expeditions for Champlain and the fur traders, travelled over much of the Great Lakes basin to encourage the profitable business of fur trading. • Hudson Bay Company was formed. King Charles granted his cousin, Prince 1670 Rupert, a charter creating HBC as a corporate entity. • From 1670 to 1870 the fur trade was the main focus of the HBC. • A powerful group, made up of nine different fur traders, developed into 1774 the North West Trading Company. They dominated the Government and considered the natural riches of the land to be the monopoly of this company. Grade Five Online Learning Activities Fur Trading in Newmarket 1603 - 1820 • Competition and jealousy raged between the North West Company and the 1793 Hudson Bay Company. -

Etienne Lucier

Etienne Lucier Readers should feel free to use information from the website, however credit must be given to this site and to the author of the individual articles. By Ella Strom Etienne Lucier was born in St. Edouard, District of Montreal, Canada, in 1793 and died on the French Prairie in Oregon, United States in 1853.1 This early pioneer to the Willamette Valley was one of the men who helped to form the early Oregon society and government. Etienne Lucier joined the Wilson Price Hunt overland contingent of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company in 1810.2 3 After the Pacific Fur Company was dissolved during the War of 1812,4 he entered the service of the North West Company and, finally, ended up being a brigade leader for the Hudson’s Bay Company.5 For a short time in 1827, he lived on what would be come known as East Portland. He helped several noted pioneers establish themselves in the northern Willamette Valley by building three cabins in Oregon City for Dr. John McLoughlin and a home at Chemaway for Joseph Gervais.6 Also as early as 1827, Lucier may have had a temporary cabin on a land claim which was adjacent to the Willamette Fur Post in the Champoeg area. However, it is clear that by 1829 Lucier had a permanent cabin near Champoeg.7 F.X. Matthieu, a man who would be instrumental in determining Oregon’s future as an American colony, arrived on the Willamette in 1842, “ragged, barefoot, and hungry” and Lucier gave him shelter for two years.8 Matthieu and Lucier were key votes in favor of the organization of the provisional government under American rule in the May 1843 vote at Champoeg. -

CONTEXT DOCUMENT on the FUR TRADE of NORTHEASTERN

CONTEXT DOCUMENT on the FUR TRADE OF NORTHEASTERN NORTH DAKOTA (Ecozone #16) 1738-1861 by Lauren W. Ritterbush April 1991 FUR TRADE IN NORTHEASTERN NORTH DAKOTA {ECOZONE #16). 1738-1861 The fur trade was the commercia1l medium through which the earliest Euroamerican intrusions into North America were made. Tl;ns world wide enterprise led to the first encounters between Euroamericar:is and Native Americans. These contacts led to the opening of l1ndian lands to Euroamericans and associated developments. This is especial,ly true for the h,istory of North Dakota. It was a fur trader, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de la Ve--endrye, and his men that were the first Euroamericans to set foot in 1738 on the lar;ids later designated part of the state of North Dakota. Others followed in the latter part of the ,eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century. The documents these fur traders left behind are the earliest knowr:i written records pertaining to the region. These ,records tell much about the ear,ly commerce of the region that tied it to world markets, about the indigenous popu,lations living in the area at the time, and the environment of the region before major changes caused by overhunting, agriculture, and urban development were made. Trade along the lower Red River, as well as along, the Misso1.:1ri River, was the first organized E uroamerican commerce within the area that became North Dakota. Fortunately, a fair number of written documents pertainir.1g to the fur trade of northeastern North 0akota have been located and preserved for study. -

The Beaver Club (1785-1827): Behind Closed Doors Bella Silverman

The Beaver Club (1785-1827): Behind Closed Doors Bella Silverman Montreal’s infamous Beaver Club (1785-1827) was a social group that brought together retired merchants and acted as a platform where young fur traders could enter Montreal’s bourgeois society.1 The rules and social values governing the club reveal the violent, racist, and misogynistic underpinnings of the group; its membership was exclusively white and male, and the club admitted members who participated in morally grotesque and violent activities, such as murder and slavery. Further, the club’s mandate encouraged the systematic “othering” of those believed to be “savage” and unlike themselves.2 Indeed, the Beaver Club’s exploitive, exclusive, and violent character was cultivated in private gatherings held at its Beaver Hall Hill mansion.3 (fig. 1) Subjected to specific rules and regulations, the club allowed members to collude economically, often through their participation in the institution of slavery, and idealize the strength of white men who wintered in the North American interior or “Indian Country.”4 Up until 1821, Montreal was a mercantile city which relied upon the fur trade and international import-exports as its economic engine.5 Following the British Conquest of New France in 1759, the fur trading merchants’ influence was especially strong.6 Increasing affluence and opportunities for leisure led to the establishment of social organizations, the Beaver Club being one among many.7 The Beaver Club was founded in 1785 by the same group of men who founded the North West Company (NWC), a fur trading organization established in 1775. 9 Some of the company’s founding partners were James McGill, the Frobisher brothers, and later, Alexander Henry.10 These men were also some of the Beaver Club’s original members.11 (figs. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time.