The H. D. Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

Walter Pater — Imagism — Objectivist Verse

22 WALTER PATER — IMAGISM — OBJECTIVIST VERSE Richard Parker (The University of Sussex) Abstract In this paper I make a two-fold argument; first that the Objectivist inheritance from modernism is, in a specific sense, Paterian, and secondly, that this Paterian influence (manifested principally in the form of the Paterian aesthetic moment) is not, as might be assumed, in conflict with the political tendencies exhibited by my central examples—Ezra Pound and Louis Zukofsky—but that the arguably apolitical aesthetic moment is in fact key to their political understandings. I will begin analysing how the Paterian moment lingers in Pound's poetry, especially his Imagist and Vorticist work, and is still at the core of his poetics when he begins The Cantos . I will then go on to argue that this same Paterian aesthetic moment continues in the early work of second-generation Modernists the Objectivists, and will look at the works of Louis as a representative example. I will then argue that this group of poets' Communism is not a break with their engagement with Paterian aestheticism, but that the Paterian moment is in fact alloyed with their understanding of Marxist-Leninism. The engagement with the far left that is generally supposed to mark these writers' defining divide with their modernist forebears will therefore be shown to be more closely linked to the older generation's practices than it might be thought and I will, finally, question the apparently aesthetic basis of Pound's alignment with the far-right. A consensus has developed regarding Walter Pater's influence upon the early stages of literary modernism. -

The Luminous Detail: the Evolution of Ezra Pound's Linguistic and Aesthetic Theories from 1910-1915

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-21-2014 12:00 AM The Luminous Detail: The Evolution of Ezra Pound's Linguistic and Aesthetic Theories from 1910-1915 John J. Allaster The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Stephen J. Adams The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © John J. Allaster 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Allaster, John J., "The Luminous Detail: The Evolution of Ezra Pound's Linguistic and Aesthetic Theories from 1910-1915" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2301. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2301 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LUMINOUS DETAIL: THE EVOLUTION OF EZRA POUND’S LINGUISTIC AND AESTHETIC THEORIES FROM 1910-1915 by John Allaster Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © John Allaster 2014 Abstract In this study John Allaster traces the evolution of Ezra Pound’s linguistic theories from the method of the Luminous Detail during 1910-12, to the theory of the Image in Imagism during 1912-13, to that of the Vortex in Vorticism during 1914-1915. -

"Ego, Scriptor Cantilenae": the Cantos and Ezra Pound

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 1991 "Ego, scriptor cantilenae": The Cantos and Ezra Pound Steven R. Gulick University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1991 Steven R. Gulick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Gulick, Steven R., ""Ego, scriptor cantilenae": The Cantos and Ezra Pound" (1991). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 753. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/753 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "EGO, SCRIPTOR CANTILENAE": THE CANTOS AND EZRA POUND An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Philosophy Steven R. Gulick University of Northern Iowa August 1991 ABSTRACT Can poetry "make new" the world? Ezra Pound thought so. In "Cantico del Sole" he said: "The thought of what America would be like/ If the Classics had a wide circulation/ Troubles me in my sleep" (Personae 183). He came to write an 815 page poem called The Cantos in which he presents "fragments" drawn from the literature and documents of the past in an attempt to build a new world, "a paradiso terreste" (The Cantos 802). This may be seen as either a noble gesture or sheer egotism. Pound once called The Cantos the "tale of the tribe" (Guide to Kulchur 194), and I believe this is so, particularly if one associates this statement with Allen Ginsberg's concerning The Cantos as a model of a mind, "like all our minds" (Ginsberg 14-16). -

Ezra Pound's Imagist Theory and T .S . Eliot's Objective Correlative

Ezra Pound’s Imagist theory and T .S . Eliot’s objective correlative JESSICA MASTERS Abstract Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot were friends and collaborators. The effect of this on their work shows similar ideas and methodological beliefs regarding theory and formal technique usage, though analyses of both theories in tandem are few and far between. This essay explores the parallels between Pound’s Imagist theory and ideogrammic methods and Eliot’s objective correlative as outlined in his 1921 essay, ‘Hamlet and His Problems’, and their similar intellectual debt to Walter Pater and his ‘cult of the moment’. Eliot’s epic poem, ‘The Waste Land’ (1922) does not at first appear to have any relationship with Pound’s Imagist theory, though Pound edited it extensively. Further investigation, however, finds the same kind of ideogrammic methods in ‘The Waste Land’ as used extensively in Pound’s Imagist poetry, showing that Eliot has intellectual Imagist heritage, which in turn encouraged his development of the objective correlative. The ultimate conclusion from this essay is that Pound and Eliot’s friendship and close proximity encouraged a similarity in their theories that has not been fully explored in the current literature. Introduction Eliot’s Waste Land is I think the justification of the ‘movement,’ of our modern experiment, since 1900 —Ezra Pound, 1971 Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) were not only poetic contemporaries but also friends and collaborators. Pound was the instigator of modernism’s first literary movement, Imagism, which centred on the idea of the one-image poem. A benefit of Pound’s theoretically divisive Imagist movement was that it prepared literary society to welcome the work of later modernist poets such as Eliot, who regularly used Imagist techniques such as concise composition, parataxis and musical rhythms to make his poetry, specifically ‘The Waste Land’ (1922), decidedly ‘modern’. -

'The Immensity of Confrontable Selves': the 'Split Subject'and Multiple Identities in the Experimental Novels of Christine Brooke-Rose Stephanie Jones

‘THE IMMENSITY OF CONFRONTABLE SELVES’: THE ‘SPLIT SUBJECT’ AND MULTIPLE IDENTITIES IN THE EXPERIMENTAL NOVELS OF CHRISTINE BROOKE-ROSE STEPHANIE JONES ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY 01/03/2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deepest thanks to my supervisor Professor Tim Woods, who has shown constant, unwavering support for the project, and read it multiple times with uncommon care. I would also like to thank Professor Peter Barry whose comments on my written work and presentations have always inspired much considered thought. I am extremely grateful to Dr. Luke Thurston for his translation of the letters between Hélène Cixous and Christine Brooke-Rose from the French. I am also greatly indebted to Dr. Will Slocombe whose bravery in teaching Brooke-Rose’s fiction should be held directly responsible for the inspiration for this project. I should also like to extend my thanks to my fellow colleagues in the English and Creative Writing department at Aberystwyth University. I am also deeply indebted to the Harry Ransom Centre of Research, the location of the Christine Brooke-Rose archive, and the John Rylands Library that holds the Carcanet archive, and all the staff that work in both institutions. Their guidance in the archives and support for the project has been deeply valued. Special thanks go to Michael Schmidt OBE for allowing me to access the Carcanet archive and Jean Michel Rabaté and Ali Smith for their encouragement throughout my studies of Christine Brooke-Rose, and their contributions to the project. For my family LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS These abbreviations will appear embedded within the text in parentheses, with page numbers. -

Imagism and Te Hulme

I BETWEEN POSITIVISM AND Several critics have been intrigued by the gap between late AND MAGISM Victorian poetry and the more »modern« poetry of the 1920s. This book attempts to get to grips with the watershed by BETWEEN analysing one school of poetry and criticism written in the first decade of the 20th century until the end of the First World War. T To many readers and critics, T.E. Hulme and the Imagists . E POSITIVISM represent little more than a footnote. But they are more HULME . than mere stepping-stones in the transition. Besides being experimenting poets, most of them are acute critics of art and literature, and they made the poetic picture the focus of their attention. They are opposed not only to the monopoly FLEMMING OLSEN T AND T.S. ELIOT: of science, which claimed to be able to decide what truth and . S reality »really« are, but also to the predictability and insipidity of . E much of the poetry of the late Tennyson and his successors. LIOT: Behind the discussions and experiments lay the great question IMAGISM AND What Is Reality? What are its characteristics? How can we describe it? Can we ever get to an understanding of it? Hulme and the Imagists deserve to be taken seriously because T.E. HULME of their untiring efforts, and because they contributed to bringing about the reorientation that took place within the poetical and critical traditions. FLEMMING OLSEN UNIVERSITY PRESS OF ISBN 978-87-7674-283-6 SOUTHERN DENMARK Between Positivism and T.S. Eliot: Imagism and T.E. -

Gained in Translation: Ezra Pound, Hu Shi, and Literary Revolution

Gained in Translation: Ezra Pound, Hu Shi, and Literary Revolution Jenine HEATON* I. Introduction Hu Shi 胡適( 1891-1962), Chinese philosopher, essayist, and diplomat, is well-known for his advocacy of literary reform for modern China. His article, “A Preliminary Discussion of Literary Reform,” which appeared in Xin Qingnian 新青年( The New Youth) magazine in January, 1917, proposed the radical idea of writing in vernacular Chinese rather than classical. Until Hu’s article was published, no reformers or revolutionaries had conceived of writing in anything other than classical Chinese. Hu’s literary revolution began with a poetic revolution, but quickly extended to literature in general, and then to expression of new ideas in all fi elds. Hu’s program offered a pragmatic means of improving communication, fostering social criticism, and reevaluating the importance of popular Chinese novels from past centuries. Hu Shi’s literary renaissance has been examined in great detail by many scholars; this paper traces the synergistic effect of ideas, people, and literary movements that informed Hu Shi’s successful literary and language revolu- tions. Hu Shi received a Boxer Indemnity grant to study agriculture at Cornell University in the United States in 1910. Two years later he changed his major to philosophy and literature, and after graduation, continued his education at Columbia University under John Dewey (1859-1952). Hu remained in the United States until 1917. Hu’s sojourn in America coincided with a literary revolution in English-language poetry called the Imagist movement that occurred in England and the United States between 1908 and 1917. Hu’s diaries indicate that he was fully aware of this movement, and was inspired by it. -

View / Open Summers Oregon 0171A 10923.Pdf

LAUGHTER SHARED OR THE GAMES POETS PLAY: THE ETHICS AND AESTHETICS OF IRONY IN POSTWAR AMERICAN POETRY by STEPHEN J. SUMMERS A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Stephen J. Summers Title: Laughter Shared or the Games Poets Play: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Irony in Postwar American Poetry This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Mark Whalan Chairperson John Gage Core Member Paul Peppis Core Member Mark Johnson Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2014 ii © 2014 Stephen J. Summers iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Stephen J. Summers Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2014 Title: Laughter Shared or the Games Poets Play: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Irony in Postwar American Poetry During and after the First World War, English-language poets employed various ironic techniques to address war’s dark absurdities. These methods, I argue, have various degrees of efficacy, depending upon the ethics of the poetry’s approach to its reading audience. I judge these ethical discourses according to a poem’s willingness to include its readers in the process of poetic construction, through a shared ironic connection. My central ethical test is Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative and Jurgen Habermas’s conception of discourse ethics. -

FIELD, Issue 33, Fall 1985

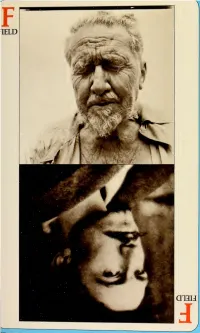

FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 3 3 FALL 1985 PUBLISHED BY OBERLIN COLLEGE OBERLIN, OHIO EOJTORS Stuart Friehert David Young ASSOCIATE Alberta Turner EDITORS David Walker BUSINESS Dolorus Nevels MANAGER EDITORIAL Lia Purpura ASSISTANT COVER Stephen j. Parkas Jr. FIELD gratefully acknowledges support from the Ohio Arts Council. Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Subscriptions and manuscripts should be sent to FIELD, Rice Hall, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio 44074. Manuscripts will not be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Subscriptions: $7.00 a year/$12.00 for two years/single issues $3.50 postpaid. Back issues 1, 4, 7, 15-31: $10.00 each. Issues 2-3, 5-6, 8-14 are out of print. Copyright ® 1985 by Oberlin College. CONTENTS 5 Ezra Pound: A Symposium Donald Hall 8 Pound's Sounds William Matthews 15 Young Ezra Stanley Plmnly 19 Pound's Garden James Laughlin 26 Rambling Around Pound's Propertius Norman Duhie 39 Into the Sere and Yellow Carol Muske 55 Alba LXXIX Charles Wright 63 Improvisations on Pound * * Sachiko Yoshihara 71 From the Afterworld Dennis Schm.itz 73 So High 75 Driving With One Light Miroslav Holuh 77 Crush Syndrome 78 Vanishing Lung Syndrome 80 Hemophilia Ralph Burns 82 Luck Charlie Smith 85 By Fire 86 Discovery Thomas Lux 87 Barracuda 88 Traveling Exhibit of Torture Instruments Garrett Kaoru Hongo 89 The Unreal Dwelling: My Years Volcano William Stafford 93 Surrounded by Mountains 94 Crowded Falls 95 Outside Wichita Susan Prospere 96 Saturnalia 99 House of Straw W1 Contributors EZRA POUND A FIELD SYMPOSIUM EZRA POUND: A SYMPOSIUM Even if this were not Ezra Pound's hundredth year, we would probably have succumbed to the urge to organize this sym- posium in his honor. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85391-0 - The Cambridge Introduction to Ezra Pound Ira B. Nadel Index More information Index Adams, Henry 18, 36, 71 Barry, Iris 46, 88 Adams, John viii, 30, 35, 63, 70, 71, 73, Bartok,´ Bela 111, 112 74, 75, 83, 119, 120 Baxter, Viola 4, 8 Adams, John Quincy 71, 74 Beach, Sylvia 10 aestheticism 21 Beckett, Samuel viii, 18, 85 Alberti, Leon Batista 68 Endgame 18 Aldington, Richard 14, 19, 20, 69, 115 Beerbohm, Max 14, 60 America 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 14, 15, 17–18, Bennett, Arnold 20, 21, 60 26, 27, 29, 35–6, 56, 57, 63, 66, Old Wives’ Tale 20 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 78, 80, Bernstein, Charles 122–3, 124, 125 102, 103, 106, 109, 110, 115, My Way, Speeches and Poems 122 119, 121 Bion 59 American West viii Bird, William 13, 84 Anderson, Margaret 1, 23, 28 Bishop, Elizabeth 16 Anglo-Saxon 4, 41, 45, 46, 49, 90 BLAST 11, 23–4, 48, 86 Antheil, George 8, 40, 85 Blunt, Wilfrid Scawen 19, 20 anthologist 1 Bollingen Prize 16, 78, 106, 114 anti-Semitism 3, 75, 95, 101, 102, 103, Book News 4 106, 107, 114, 117, 121, Book of the Rhymer’s Club 6 123 Bordeaux 4 Aristotle 87, 95, 100, 102 Bornstein, George 123 Arnaut Daniel 29, 38, 40, 41, 54, Bottome, Phyllis 7 107 Brancusi 13 Arnold, Matthew 2–3, 41, 56 Brandt, Bill 22 Culture and Anarchy 2 British Museum 6, 9, 42, 47, 97, 106 “George Sand” 56 Brooke, Rupert 108 art 37 Browning 6, 10, 24, 31, 32, 39, 41, 44, Ashbery, John 107 47, 55, 90, 109, 116, 118, 122 Atheling, William 8 Dramatis Personae 44 avant-garde 21, 23, 24, 98, 103 Ring and The Book, The 31 Sordello 10, 31, 47, 122 Bacigalupo, Massimo 127 Brunnenburg 2, 27 Barnard, Mary 1, 89 Bunting, Basil 14, 63, 89, 90, 102, 104, Barney, Natalie 13 111, 113, 126 138 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85391-0 - The Cambridge Introduction to Ezra Pound Ira B. -

Ezra Pound: the Rise and Fall of the London Vortex

FACULTEIT LETTEREN EN WIJSBEGEERTE VAKGROEP ENGELSE LITERATUUR ACADEMIEJAAR 2007–2008 EZRA POUND: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LONDON VORTEX FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF PIERRE BOURDIEU’S FIELD OF CULTURAL PRODUCTION FREDERICK MOREL PROMOTOR: PROF. DR. M. DEMOOR. SCRIPTIE INGEDIEND TOT HET BEHALEN VAN DE GRAAD VAN MASTER IN DE TAAL-EN LETTERKUNDE: ENGELS Morel | i I would like to thank Prof. Dr. M. Demoor for her dedication, her support, and for believing in me. Morel | ii List of Illustrations Numbers refer to pages 30 Ezra Pound. Cartoon of Pound as a dandy by “Tom T,” in the NewAge, October 1913. Courtesy of Robert Scholes. 38 Wyndham Lewis. Photo by Hulton Archive. 44 Symbol of the Vortex, in BLAST June 1914. 47 “Alcibiades” by Wyndham Lewis, 1912. 49 Cover of the first issue of BLAST, June 20, 1914. 50 Manifesto from the first issue of BLAST, June 20, 1914. 51 Cover of the second issue of BLAST, (“Before Antwerp” by Wyndham Lewis), July 1915. Estate of Mrs. Gladys Anne Wyndham Lewis. 57 Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound, c. 1914. Nasher Sculpture Center, photograph by David Heald. Morel | 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Ezra Loomis Pound: Background ................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Research Question and Aim .......................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Theoretical Embedding and