SHS Articles on the Cistercian Order.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

Abbot Suger's Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis

DE CONSECRATIONIBUS: ABBOT SUGER’S CONSECRATIONS OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. DENIS by Elizabeth R. Drennon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth R. Drennon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Elizabeth R. Drennon Thesis Title: De Consecrationibus: Abbot Suger’s Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Elizabeth R. Drennon, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Erik J. Hadley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa McClain, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION I dedicate this to my family, who believed I could do this and who tolerated my child-like enthusiasm, strange mumblings in Latin, and sudden outbursts of enlightenment throughout this process. Your faith in me and your support, both financially and emotionally, made this possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lisa McClain for her support, patience, editing advice, and guidance throughout this process. I simply could not have found a better mentor. -

Newsletter No. 17

Newsletter No. 17 May 2019 ON SUNDAY MARCH 24TH there was a Group visit to the site of Sibton Abbey, near Yoxford in Suffolk. Sibton Abbey was founded by the Cistercians in 1150, and was a sister house of Tilty and Sawtry, all three being daughter houses of Warden Abbey in Bedfordshire. The remains of the Abbey are currently being renovated, on behalf of Historic England, by R & J Hogg Ltd. – the same company that did the restoration work at Tilty in 2013. There are fairly extensive ruins still standing, though much of the site has hitherto been quite overgrown. David Kenny had kindly made arrangements for our visit, with the Sibton Abbey Estate, and led us on a ‘walk and talk’ around the site. The architect, and some of the builders from Hoggs, were also there on the day, and conducted optional scaffold tours for us. It was great to have the opportunity to take a closer look at some the restoration work. We were given a warm welcome by the Friends of St. Peter’s Church, Sibton, some of whom also joined us for the tour. It was an interesting and enjoyable visit, finished off with lunch at a local pub, before a drive home in the sunshine through some beautiful countryside. More information about Sibton Abbey can be found here: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1018327 G E N E R A L M E E T IN G S The AGM in JANUARY was very successful. There was an excellent turn-out for the meeting, and the Upstairs Room was packed. -

National Regional State Aid Map: France (2007/C 94/13)

C 94/34EN Official Journal of the European Union 28.4.2007 Guidelines on national regional aid for 2007-2013 — National regional State aid map: France (Text with EEA relevance) (2007/C 94/13) N 343/06 — FRANCE National regional aid map 1.1.2007-31.12.2013 (Approved by the Commission on 7.3.2007) Names of the NUTS-II/NUTS-III regions Ceiling for regional investment aid (1) NUTS II-III Names of the eligible municipalities (P: eligible cantons) (Applicable to large enterprises) 1.1.2007-31.12.2013 1. NUTS-II regions eligible for aid under Article 87(3)(a) of the EC Treaty for the whole period 2007-2013 FR93 Guyane 60 % FR91 Guadeloupe 50 % FR92 Martinique 50 % FR94 Réunion 50 % 2. NUTS-II regions eligible for aid under Article 87(3)(c) of the EC Treaty for the whole period 2007-2013 FR83 Corse 15 % 3. Regions eligible for aid under Article 87(3)(c) of the EC Treaty for the whole period 2007-2013 at a maximum aid intensity of 15% FR10 Île-de-France FR102 Seine-et-Marne 77016 Bagneaux-sur-Loing; 77032 Beton-Bazoches; 77051 Bray-sur-Seine; 77061 Cannes-Ecluse; 77073 Chalautre-la-Petite; 77076 Chalmaison; 77079 Champagne-sur-Seine; 77137 Courtacon; 77156 Darvault; 77159 Donnemarie-Dontilly; 77166 Ecuelles; 77167 Egligny; 77170 Episy; 77172 Esmans; 77174 Everly; 77182 La Ferté-Gaucher; 77194 Forges; 77202 La Genevraye; 77210 La Grande-Paroisse; 77212 Gravon; 77236 Jaulnes; 77262 Louan- Villegruis-Fontaine; 77263 Luisetaines; 77275 Les Marêts; 77279 Marolles-sur-Seine; 77302 Montcourt-Fromonville; 77305 Montereau-Fault-Yonne; 77325 Mouy-sur-Seine; 77333 Nemours; 77379 Provins; 77396 Rupéreux; 77403 Saint-Brice; 77409 Saint-Germain-Laval; 77421 Saint-Mars-Vieux- Maisons; 77431 Saint-Pierre-lès-Nemours; 77434 Saint-Sauveur-lès-Bray; 77452 Sigy; 77456 Soisy-Bouy; 77467 La Tombe; 77482 Varennes-sur-Seine; 77494 Vernou-la-Celle-sur-Seine; 77519 Villiers-Saint-Georges; 77530 Voulton. -

The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux

CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX THE FIRST LIFE OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre Translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices 161 Grosvenor Street Athens, Ohio 45701 www.cistercianpublications.org In the absence of a critical edition of Recension B of the Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi, this translation is based on Mount Saint Bernard MS 1, with section numbers inserted from the critical edition of Recension A (Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi Claraevallis Abbatis, Liber Primus, ed. Paul Verdeyen, CCCM 89B [Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011]). Scripture texts in this work are translated by the translator of the text. The image of Saint Bernard on the cover is a miniature from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, fol. 1, reprinted with permission from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey. © 2015 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, College- ville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vita prima Sancti Bernardi. English The first life of Bernard of Clairvaux / by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre ; translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO. -

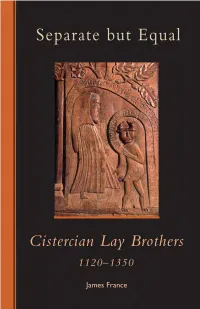

Separate but Equal: Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120-1350

All content available from the Liturgical Press website is protected by copyright and is owned or controlled by Liturgical Press. You may print or download to a local hard disk the e-book content for your personal and non-commercial use only equal to the number of copies purchased. Each reproduction must include the title and full copyright notice as it appears in the content. UNAUTHORIZED COPYING, REPRODUCTION, REPUBLISHING, UPLOADING, DOWNLOADING, DISTRIBUTION, POSTING, TRANS- MITTING OR DUPLICATING ANY OF THE MATERIAL IS PROHIB- ITED. ISBN: 978-0-87907-747-1 CISTERCIAN STUDIES SERIES: NUMBER TWO HUNDRED FORTY-SIX Separate but Equal Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120–1350 by James France Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices Abbey of Gethsemani 3642 Monks Road Trappist, Kentucky 40051 www.cistercianpublications.org © 2012 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, mi- crofiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data France, James. Separate but equal : Cistercian lay brothers, 1120-1350 / by James France. p cm. — (Cistercian studies series ; no. 246) Includes bibliographical references (p. -

2019 Pilgrimage Through the French Monasticism Movement

2019 Pilgrimage through the French Monasticism Movement We invite you to pilgrimage through France to observe the French Monasticism movement, the lessons it holds for the church today and for your own personal spiritual growth. We will visit Mont St-Michel, stay in the monastery at Ligugé, spend a weekend immersed in the Taizé Community, and make stops in other historic and contemporary monastic settings. Our days and reflections will be shaped by both ancient and contemporary monastic practices. Itinerary Days 1 and 2 – Arrive Paris and visit Chartres We will begin our pilgrimage by traveling from the Paris airport to Chartres Cathedral where we will begin and dedicate our pilgrimage by walking the massive labyrinth laid in the floor of the nave just as pilgrims have done before us for nearly 800 years. We will spend the night in Chartres at The Hôtellerie Saint Yves, built on the site of an ancient monastery and less than 50 m from the cathedral. Day 3 and 4 – Mont-Saint-Michel and Ligugé In the morning, we will travel to the mystical islet of Mont-Saint-Michel, a granite outcrop rising sharply (to 256 feet) out of Mont-Saint-Michel Bay (between Brittany and Normandy). We will spend the day here and return on Sunday morning to worship as people have since the first Oratory was built in the 8th Century. After lunch on the mount we will head to Ligugé Monastery for the night. Day 5 – Vézelay Following the celebration of Lauds and breakfast at Ligugé, we will depart for the hilltop town of Vézelay. -

Glasses of Wine Sparkling Wine

GLASSES OF WINE SPARKLING WINE CHAMPAGNE Germar Breton 19 Guillaume Sergent, Les Prés Dieu, Blanc de Blancs 2018 24 Charles Heidsieck, Réserve, Rosé 25 Krug, Grande Cuvée, 169ème Edition 45 SHERRY WINE FINO Equipo Navazos, Bota #54, Jerez de La Frontera 10 MANZANILLA Bodegas Barrero, Gabriela Oro en Rama, 9 Sanlúcar de Barrameda OLOROSO Emilio Hidalgo, Gobernador, Jerez de La Frontera 8 ROSÉ WINE SYRAH Château La Coste, Grand Vin, Coteaux d'Aix, 13 Provence, France 2020 MOURVÈDRE Château de Pibarnon, Bandol, Provence, France 2019 15 GLASSES OF WHITE WINE GRÜNER VELTLINER Weingut Jurtschitsch, Löss, Kamptal, Austria 2018 13 RIESLING Weingut Odinstal, Vulkan, Trocken, Pfalz, Germany 2018 29 CHENIN BLANC Domaine du Closel, La Jalousie, Savennières, 20 Loire Valley, France 2018 SAUVIGNON BLANC Vincent Pinard, Grand Chemarin, Sancerre, 22 Loire Valley, France 2018 TOCAI FRIULANO Massican, Annia, Napa Valley, California, 19 United States 2018 MARSANNE J.L. Chave Sélection, Blanche, Hermitage, 21 Rhône Valley, France 2016 SAVAGNIN Domaine de La Borde, Foudre à Canon, 17 Arbois-Pupillin, Jura, France 2018 CHARDONNAY Gérard Tremblay, Côte de Léchet, 15 Chablis Premier Cru, Burgundy, France 2018 Domaine Larue, Le Trézin, Puligny-Montrachet, 26 Burgundy, France 2018 Racines, Bentrock, Sta. Rita Hills, 38 California, United States 2017 GLASSES OF RED WINE GAMAY NOIR Jean-Claude Lapalu, Vieilles Vignes, Brouilly, 13 Beaujolais, France 2019 PINOT NOIR Domaine Alain Michelot, Vieilles Vignes, 25 Nuits-Saint-Georges, Burgundy, France 2015 Tyler, Dierberg, Block 5, Santa Maria Valley, 29 California, United States 2013 BLAUFRÄNKISCH Markus Altenburger, Leithaberg, Burgenland, 16 Austria 2017 CABERNET FRANC Domaine des Roches Neuves, Franc de Pied, 21 Saumur-Champigny, Loire Valley, France 2018 SYRAH René Rostaing, Ampodium, Côte-Rôtie, 27 Rhône Valley, France 2014 NEBBIOLO G.D. -

Géoarchéologie Du Site Antique De Molesme En Vallée De Laigne (Côte

Géoarchéologie du site antique de Molesme en vallée de Laigne (Côte-d’Or) : mise en évidence de l’impact anthropique sur la sédimentation alluviale Christophe Petit, Christian Camerlynck, Eline Deweirdt, Christophe Durlet, Jean-Pierre Garcia, Emilie Gauthier, Vincent Ollive, Hervé Richard, Patrice Wahlen To cite this version: Christophe Petit, Christian Camerlynck, Eline Deweirdt, Christophe Durlet, Jean-Pierre Garcia, et al.. Géoarchéologie du site antique de Molesme en vallée de Laigne (Côte-d’Or) : mise en évidence de l’impact anthropique sur la sédimentation alluviale. Gallia - Archéologie de la France antique, CNRS Éditions, 2006, 63, pp.263-281. 10.3406/galia.2006.3298. hal-01911071 HAL Id: hal-01911071 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01911071 Submitted on 8 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License GÉOARCHÉOLOGIE DU SITE ANTIQUE DE MOLES M E EN VA LLÉE DE LAIGNE (CÔTE -D’OR) Mise en évidence de l’impact anthropique sur la sédimentation alluviale Christophe PETIT 1, Christian CA M ERLYNCK 2, Eline DEWEIRDT 1, Christophe DURLET 3, Jean-Pierre GARCIA 3, Émilie GAUTHIER 4, Vincent OLLIVE 3, Hervé RICHARD 4, Patrice WAHLEN 5 Mots-clés. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Colleague, Critic, and Sometime Counselor to Thomas Becket

JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History–Doctor of Philosophy 2021 ABSTRACT JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter John of Salisbury was one of the best educated men in the mid-twelfth century. The beneficiary of twelve years of study in Paris under the tutelage of Peter Abelard and other scholars, John flourished alongside Thomas Becket in the Canterbury curia of Archbishop Theobald. There, his skills as a writer were of great value. Having lived through the Anarchy of King Stephen, he was a fierce advocate for the liberty of the English Church. Not surprisingly, John became caught up in the controversy between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and successor to Theobald as archbishop of Canterbury. Prior to their shared time in exile, from 1164-1170, John had written three treatises with concern for royal court follies, royal pressures on the Church, and the danger of tyrants at the core of the Entheticus de dogmate philosophorum , the Metalogicon , and the Policraticus. John dedicated these works to Becket. The question emerges: how effective was John through dedicated treatises and his letters to Becket in guiding Becket’s attitudes and behavior regarding Church liberty? By means of contemporary communication theory an examination of John’s writings and letters directed to Becket creates a new vista on the relationship between John and Becket—and the impact of John on this martyred archbishop. -

Prelims and Contents

adamo-003-front 22/05/2014 9:05 AM Page i New Monks in Old Habits Medieval monasticism was not uniform and monolithic. Even after the ninth-century adoption of the Rule of Benedict as the standard for most monasteries throughout the Carolingian Empire, there was wide variation in its practice. The eleventh to the thir- teenth centuries, a time of especially great religious ferment, saw the growth of a num- ber of movements seeking to reform monastic practice, to make it more ascetic, more “true” to the Regula Benedicti. In the early thirteenth century, the Franciscan and Domini- can Friars were the agents of reform, and many historians see the Friars as a watershed in the history of religious life in the Middle Ages. Yet when Francis of Assisi was only eleven years old, when the creation of the Franciscan life was barely an idea, monasticism in Burgundy experienced another reform. This was the foundation of the Caulite Order. The Caulites founded their first monastery in 1193, roughly a century after the advent of the Cistercians, barely two decades before the advent of the Franciscans. The order, also referred to as the Valliscaulians, was named for the site of this first monastery in Val-des- Choux or “valley of cabbages,” located in the Châtillon forest, some twelve kilometers southeast of the town of Châtillon-sur-Seine in northwest Burgundy. The most important benefactor of the order was Odo III, duke of Burgundy. The order’s spiritual founder was a certain Viard, sometimes called Guy or Guido, who, according to eighteenth-century mémoires of the order, was a former Carthusian lay brother.