Pedersen, K., E. J. B. Manning, and J. L. Corn. 2008. Distribution Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hurricane Irma's Hard Lessons

FLORIDAKEYS SEAFOOD FESTIVAl FISHING THE FLORIDAKEYS Howman fillets Acold frontcame does is taketo through, making stagethis event? 1B the fishing hot, 5B VOLUME 65-NO.3 STAY CONNECTED /KEYSINFONET NEWSAll DAY. YOUR WAY. WWW.FLKEYSNEWS.COM FACEBOOK.COM WEDNESDAY JANUARY10,2018 50 cents THE FLORIDAKEYS 7786790 22222 IN MEMORIUM AFTER THE STORM Dolphin activist Rector dies at age68 Former marine-park trainer devoted lifetocampaigning against keeping dolphins in captivity. BY KEVIN WADLOW [email protected] Russ Rector, adogged defender of Florida Keys dolphins and all ocean creatures, died Sunday in Broward County. Rector, 68,was an indefatigable critic of marine-mammal captivity and founder of the Dolphin Freedom Foun- KEVINWADLOWKeynoter dation. After working for seven years as Monroe County EmergencyManagementDirector MartySenterfitt and county strategic planner Kimberly Matthews respond to adolphin trainer at Fort Lauderdale’s questions and complaints during Monday’sKey Largo feedback session on Hurricane Irma response. Additional sessions takeplace Ocean World marine park until 1975, through Jan. 22. he quit over concerns about marine- mammal captivity and protested against the park until it closed in 1994. In the Keys, Rector supported rescue- and-release efforts for marine mammal strandings but harbored strong opin- Hurricane Irma’s hardlessons ions against several local dolphin facil- ities. He was aconstant thorn in the side of Florida Keys residents voice knowledge did not exist,” thews, county director of stra- Senterfitt said officials re- the Miami Seaquarium, identifying concern about debris,re-entry county Emergency Manage- tegic planning. “That’s one of ceiving requests for re-entry undersized animal tanks and code andlack of information at ment Director Marty Senterfitt the things at the top of our exceptions “struggled with this violations that required expensive fixes. -

Appendix C - Monroe County

2016 Supplemental Summary Statewide Regional Evacuation Study APPENDIX C - MONROE COUNTY This document contains summaries (updated in 2016) of the following chapters of the 2010 Volume 1-11 Technical Data Report: Chapter 1: Regional Demographics Chapter 2: Regional Hazards Analysis Chapter 4: Regional Vulnerability and Population Analysis Funding provided by the Florida Work completed by the Division of Emergency Management South Florida Regional Council STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY This page intentionally left blank. STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY Page A. Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 B. Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 C. Demographic Trends ...................................................................................... 4 D. Census Maps .................................................................................................. 9 E. Hazard Maps .................................................................................................15 F. Critical Facilities Vulnerability Analysis .............................................................23 List of Tables Table 1 Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 Table 2 Health Care Facilities Vulnerability -

Florida's #1 Visitors Guide© Destinatiolntm FLORIDA

Fall 2020 Florida's #1 Visitors Guide© DESTINATIOlNTM FLORIDA Meet Robert The Most Haunted Doll in the World! Cigars, Food & Art The Cuban/Key West Connection Music to Your Ears Key Largo’s Original Music Festival FLORIDA KEYS & KEY WEST Life here is so endlessly delicious… If you want to discover where to indulge in good food and good times during your next Florida adventure, visit us at DestinationFlorida.com. DESTINATIOlNTM FLORIDA • Florida Keys & Key West • Greater Tampa Bay • St Pete • Sarasota • Clearwater • Cedar Key • Gainesville • Bonita Springs • Charlotte Harbor • Englewood Beach • Everglades • Fort Myers • Fort Myers Beach • Marco Island • Naples • Punta Gorda • Sanibel-Captiva • Daytona • Ormond Beach • New Smyrna • Port Orange • The Palm Beaches 10-13 Arts Scene 22 Unplugged 31-45 Good Eats DESTINATIOlNTM FLORIDA what’s inside... Florida Keys & Key West Publishers 6 - 8 Top Picks 24 The Dolphins’ Tale Karen L. Davis/Pamela Childs The Best of the Florida Keys & Key West Dolphin Research Center Comptroller 11 For the Birds 26 The Perfect Cure for the Karen Davis Pulitzer Prize Artist Jeff MacNelly COVID 19 Blues Marketing/Creative Director Key West Tropical Forest & Pamela Childs 10 - 13 Arts Scene Botanical Garden Galleries & Museums you won’t want to Art Director/Brand Manager miss 31 - 45 Good Eats Marsha Michaels Cool spots to eat, drink and party Account Manager Key West 14 - 15 Walk this Way Peter Arnow Key West’s Colorful Historic Adventure 44 Key West’s Best Sunday Brunch Bistro 45 Adventure Contributor 16 - 17 Cigars, Food, Art & Culture Mayor Gonzo Mays The Cuban/Key West Connection 45 SOCA Signature recipe from Islamorada’s Photographer At Large 18 Meet Robert acclaimed “A Moveable Feast” Food Truck Peter Arnow The Most Haunted Doll in the World Webmaster 46 - 48 What’s On The Menu? Lance Belew 19 A Tour-de-Force One Man Show Sample menus from the Keys’ top Randy Roberts Live! restaurants PUBLISHED QUARTERLY 20 Key West’s Coolest Cats 99 - 54 Shop P.O. -

Florida Keys Terrestrial Adaptation Planning (Keystap) Species

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330842954 FLORIDA KEYS TERRESTRIAL ADAPTATION PROJECT: Florida Keys Case Study on Incorporating Climate Change Considerations into Conservation Planning and Actions for Threatened and Endang... Technical Report · January 2018 CITATION READS 1 438 6 authors, including: Logan Benedict Jason M. Evans Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Stetson University 2 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION 87 PUBLICATIONS 983 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Conservation Clinic View project Vinson Institute Policy Papers View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jason M. Evans on 27 April 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. USFWS Cooperative Agreement F16AC01213 Florida Keys Case Study on Incorporating Climate Change Considerations into Conservation Planning and Actions for Threatened and Endangered Species Project Coordinator: Logan Benedict, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Project Team: Bob Glazer, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Chris Bergh, The Nature Conservancy Steve Traxler, US Fish and Wildlife Service Beth Stys, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Jason Evans, Stetson University Project Report Photo by Logan Benedict Cover Photo by Ricardo Zambrano 1 | Page USFWS Cooperative Agreement F16AC01213 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................................... -

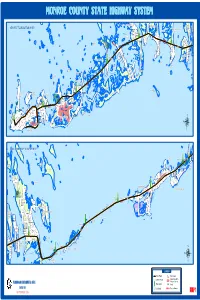

Highway System

V O D L D S C T E R VD D REY BL A CORAL AVE MIDDLE O T TORCH HOWE L WISTERIA E RESERVATION P KEY R NAVAL U.S. H KEY O LESRONDE DR I N A ISLAND MARTINIQUE LN MARTINIQUE T D D O A B R R INDIES DR R N 4 OW A C T A H J N S DEERKEY FAT MIDDLE TO KEY TORCH MIDDLE WESTTO KEY TORCH KEY B H I A D G R N T A A R M A U G R L I T M A U A B U I R I C O TORCH RD A MIDDLE C L I R L I D D A N E D L O L A L S S N N L C L L H I N N A E N N MARY RD N W E E L E RD MILLS W O D FRONT ST PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL OFFICE G O E PINE ST W A BA W YV IEW H A D D I R R T T E E !9/% GILLOTT RD H R A D E E D V A M R D R M G E S A GEORGE R T T D C D O S R U CH T CH A A EL L NN R F L RD RES K O SHO I C CORAL S N B Y GULF STREAM ST L MUNITIONS O O D I L A L A N STORAGE NAVY U.S. U U V E N A T E M T N D R G TRINID AD RD B S KEY DEERKEY NATIONAL E H S WILDLIFE U E T REFUGE SEPTEMBER 2006 L T R L T ALOHA D L A Y M V I R J A A C D A A O N R D D I C S E S N W L A D V E T T S L A H T Y PARK AVE V S I PIRATES RD E T R O A I S ANNETTE N O U H E BARRY AVE G G T BRYANT AVE S KEY PINE BIG T H E W A S P H T W R L A F V I S T I I T E 6 F KEY N T A R D E T E L T E S D S C DISTRICT SIX O A S H N R T T KEY FLEMING AIR STATION AIR NAVAL U.S. -

Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan

Monroe County Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Prepared for Monroe County by Camp Dresser & McKee, Inc. August 2001 file:///F|/GSG/PDF Files/Stormwater/SMMPCover.htm [12/31/2001 3:10:29 PM] Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Acknowledgements Monroe County Commissioners Dixie Spehar (District 1) George Neugent, Mayor (District 2) Charles "Sonny" McCoy (District 3) Nora Williams, Mayor Pro Tem (District 4) Murray Nelson (District 5) Monroe County Staff Tim McGarry, Director, Growth Management Division George Garrett, Director, Marine Resources Department Dave Koppel, Director, Engineering Department Stormwater Technical Advisory Committee Richard Alleman, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Paul Linton, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Murray Miller, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Dave Fernandez, Director of Utilities, City of Key West Roland Flowers, City of Key West Richard Harvey, South Florida Office U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Ann Lazar, Department of Community Affairs Erik Orsak, Environmental Contaminants, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Gus Rios, Dept. of Environmental Protection Debbie Peterson, Planning Department, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Teresa Tinker, Office of Planning and Budgeting, Executive Office of the Governor Eric Livingston, Bureau Chief, Watershed Mgmt, Dept. of Environmental Protection AB i C:\Documents and Settings\mcclellandsi\My Documents\Projects\SIM Projects\Monroe County SMMP\Volume 1 Data & Objectives Report\Task I Report\Acknowledgements.doc Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Stormwater Technical Advisory Committee (continued) Charles Baldwin, Islamorada, Village of Islands Greg Tindle, Islamorada, Village of Islands Zulie Williams, Islamorada, Village of Islands Ricardo Salazar, Department of Transportation Cathy Owen, Dept. of Transportation Bill Botten, Mayor, Key Colony Beach Carlos de Rojas, Regulation Department, South Florida WMD Tony Waterhouse, Regulation Department, South Florida WMD Robert Brock, Everglades National Park, S. -

Distribution and Abundance of Endangered Florida Key Deer on Outer Islands Author(S): Dominique E

Distribution and Abundance of Endangered Florida Key Deer on Outer Islands Author(s): Dominique E. Watts, Israel D. Parker, Roel R. Lopez, Nova J. Silvy, and Donald S. Davis Source: Journal of Wildlife Management, 72(2):360-366. 2008. Published By: The Wildlife Society DOI: 10.2193/2007-166 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2193/2007-166 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Management and Conservation Article Distribution and Abundance of Endangered Florida Key Deer on Outer Islands DOMINIQUE E. WATTS,1 Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA ISRAEL D. PARKER, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA ROEL R. LOPEZ, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA NOVA J. SILVY, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA DONALD S. -

Fema-Administration-Of-National-Flood

complaint in 2003, the plaintiffs filed suit against FEMA and the Service pursuant to the Act and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) (79 Stat. 404; 5 U.S.C. 500 et seq.). The plaintiffs won a Summary Judgment on all three counts of their complaint. On March 29, 2005, the United States District Court, Southern District of Florida (Court) issued an Order ruling the Service and FEMA violated the Act and the APA. Specifically, the Court found: (1) the Service and FEMA violated the Act’s section 7(a)(2) and APA’s prohibition against actions that are arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with the law by failing to protect against jeopardy; (2) the Service and FEMA failed to ensure against adverse modification of critical habitat for the endangered silver rice rat; and (3) FEMA failed to develop and implement a conservation program for listed species under section 7(a)(1) of the Act. On September 9, 2005, the Court granted the plaintiffs’ motion for an injunction against FEMA issuing flood insurance on any new residential or commercial developments in suitable habitats of federally listed species in the Keys. The injunction applied to properties on a list of potential suitable habitat submitted to the Court by the Service. Plaintiffs have stipulated to the removal of some properties on the suitable habitat list based on Plaintiffs’ determination that the properties were not located in suitable habitat, thereby enabling some owners to obtain flood insurance. The Court also ordered the Service to submit a new BO by August 9, 2006. -

LKS Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

LKS bus time schedule & line map LKS Lower Keys Shuttle View In Website Mode The LKS bus line (Lower Keys Shuttle) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Big Pine: 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM (2) Big Pine: 7:49 PM (3) Holiday Inn: 10:10 AM - 8:47 PM (4) Marathon: 5:40 AM - 5:59 PM (5) Stock Island/Key West: 5:35 AM - 8:47 PM (6) Sugarloaf: 9:26 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest LKS bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next LKS bus arriving. Direction: Big Pine LKS bus Time Schedule 24 stops Big Pine Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM Monday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM Holiday Inn 13201 Overseas Highway, Marathon Tuesday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM Us1 & Sadowski Causeway Wednesday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM Us1 & 123rd Street Thursday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM 12350 Overseas Hwy, Marathon Friday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM Us1 & 109th Street Saturday 9:20 AM - 8:09 PM Marathon - Airport Marathon - Reef Club 6799 Overseas Hwy, Marathon LKS bus Info Direction: Big Pine Marathon - Bb&T Stops: 24 6090 Overseas Hwy, Marathon Trip Duration: 38 min Line Summary: Holiday Inn, Us1 & Sadowski Us1 & 52nd Street Causeway, Us1 & 123rd Street, Us1 & 109th Street, Sombrero Beach Road, Marathon Marathon - Airport, Marathon - Reef Club, Marathon - Bb&T, Us1 & 52nd Street, Marathon - 41st Street, Marathon - 41st Street Marathon - Fhp & School, Marathon - Government 100 41st St Gulf, Marathon Center, Marathon - Coast Guard Station, Marathon - Prior To Turn Key Marina, Sunshine Key - Marathon - Fhp & School Campground Entrance, Bahia Honda - -

Florida Keys Mile-Marker Guide

Road Trip: Florida Keys Mile-Marker Guide Overseas Highway, mile by mile: Plan your Florida Keys itinerary The Overseas Highway through the Florida Keys is the ultimate road trip: Spectacular views and things to do, places to go and places to hide, hidden harbors and funky tiki bars. There are hundreds of places to pull over to fish or kayak or enjoy a cocktail at sunset. There are dozens of colorful coral reefs to snorkel or dive. Fresh seafood is a Florida Keys staple, offered at roadside fish shacks and upscale eateries. For many, the destination is Key West, at the end of the road, but you’ll find the true character of the Florida Keys before you get there. This mile-marker guide will help you discover new things to see and do in the Florida Keys. It’s a great tool for planning your Florida Keys driving itinerary. Card Sound Road 127.5 — Florida City – Junction with Fla. Turnpike and U.S. 1. 126.5 — Card Sound Road (CR-905) goes east to the Card Sound Bridge and northern Key Largo. If you’re not in a hurry, take the toll road ($1 toll). Card Sound Road traverses a wild area that once had a small community of Card Sound. All that’s left now is Alabama Jack’s, a funky outdoor restaurant and tiki bar known for its conch fritters and the line of motorcycles it attracts. (Don’t be afraid; it’s a family oriented place and great fun.) If you take Card Sound Road, you’ll pass a little-known park, Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park, before coming to Key Largo itself. -

Florida Keys P E!

FLORIDA KEYS AQUEDUCT AUTHORITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ MEETING Open to the Public Florida Keys Mosquito Control District 503 107th Street Marathon, Florida 33050 Wednesday, July 26, 2017 10:30 a.m. PUBLIC HEARINGS Presentation on Proposed Budget for Fiscal Year 2018 and Proposed Water Rate Increase REGULAR MEETING AGENDA INVOCATION PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE EMPLOYEE AWARDS Juan Lopez – 15 Years of Service Aaron Sipe – 10 Years of Service EMPLOYEE OF THE YEAR Natalie Allen RETIREMENT Mark Theobald APPROVAL OF MINUTES June 28, 2017 Board Meeting ADDITIONS/DELETIONS TO AGENDA ACCEPTANCE OF AGENDA Note: The Board of Directors does allow time for comments from the public, who have completed sign-in cards, on any Agenda Item or any specific areas of concern. Individuals will be allotted 3 minutes to make presentation. Representatives from established groups will be allotted 5 minutes to make presentation. FKAA Agenda – July 26, 2017 Page 2 CONSENT AGENDA ITEMS OFFICE OF COUNSEL 1. OOC – 01 Consideration to approve payment to Bryant, Miller & Olive for professional services rendered and expenses incurred for the month of May 2017 regarding defense of declaratory judgment, Delaney & Kulikowsky vs. Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority and Monroe County ($1,228.06 Monroe County) DIVISION OF UTILITY OPERATIONS 2. DUO – 01 Consideration to approve the abandonment of right-of-way described as a portion of Severino Drive in Islamorada, Florida as shown on Venetian Shores Plat No. 3 according to Plat thereof as recorded in Plat Book 5, Page 48 of the Public Records -

Property Type Year to Date Activity Report

Property Type Year to Date Activity Report For 01/01/2013 To 4/17/2013 Current Sold Average % Of Coop Coop Property Type Key/Island New Pend Sold DOM Expr Withdrawn Active Volume Sales Price List Sales Volume Residential Big Coppitt 31 17 4 9 3,665,000 407,222 206 93.3 6 2,655,000 3 2 Residential Big Pine Key 114 75 34 36 10,025,800 278,494 238 92.3 27 7,487,500 14 12 Residential Big Torch Key 1 3 2 0 88 0 0 0 Residential Boca Chica Key 1 1 0 0 52 0 0 1 Residential Coco Plum 14 8 6 8 2,583,000 322,875 247 89.3 8 2,583,000 2 0 Residential Conch Key 5 0 1 0 318 0 0 0 Residential Coral Key 1 0 0 1 625,000 625,000 1,903 83.4 1 625,000 0 0 Residential Cudjoe Key 131 62 13 19 8,946,833 470,886 239 89.2 14 7,030,833 12 5 Residential Duck Key 51 22 5 10 6,434,000 643,400 284 94.2 9 5,509,000 3 1 Residential Geiger Key 3 0 0 4 1,113,000 278,250 155 90.0 2 793,000 0 0 Residential Grassy Key 22 10 4 4 1,110,000 277,500 239 94.8 4 1,110,000 3 2 Residential Key Colony 92 58 14 15 7,793,000 519,533 256 94.0 13 6,643,000 11 0 Residential Key Haven 25 16 1 7 9,129,000 1,304,143 206 95.9 5 4,979,000 2 1 Residential Key Largo 407 227 87 126 47,444,572 376,544 274 92.6 98 40,331,072 59 25 Residential Key West 609 292 46 165 86,015,821 521,308 266 94.0 134 70,772,571 40 13 Residential Little Torch Key 22 18 6 9 3,248,000 360,889 292 90.1 6 2,198,000 20 2 Residential Long Key 10 5 4 5 1,207,520 241,504 236 93.8 2 310,000 3 1 Residential Lower Matecumbe 89 30 7 9 6,310,750 701,194 487 91.5 8 5,945,750 9 0 Residential Marathon 218 128 47 81 26,778,410 330,598