Arxiv:2101.04478V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 15 Jan 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

115 Abell Galaxy Cluster # 373

WINTER Medium-scope challenges 271 # # 115 Abell Galaxy Cluster # 373 Target Type RA Dec. Constellation Magnitude Size Chart AGCS 373 Galaxy cluster 03 38.5 –35 27.0 Fornax – 180 ′ 5.22 Chart 5.22 Abell Galaxy Cluster (South) 373 272 Cosmic Challenge WINTER Nestled in the southeast corner of the dim early winter western suburbs. Deep photographs reveal that NGC constellation Fornax, adjacent to the distinctive triangle 1316 contains many dust clouds and is surrounded by a formed by 6th-magnitude Chi-1 ( 1), Chi-2 ( 2), and complex envelope of faint material, several loops of Chi-3 ( 3) Fornacis, is an attractive cluster of galaxies which appear to engulf a smaller galaxy, NGC 1317, 6 ′ known as Abell Galaxy Cluster – Southern Supplement to the north. Astronomers consider this to be a case of (AGCS) 373. In addition to his research that led to the galactic cannibalism, with the larger NGC 1316 discovery of more than 80 new planetary nebulae in the devouring its smaller companion. The merger is further 1950s, George Abell also examined the overall structure signaled by strong radio emissions being telegraphed of the universe. He did so by studying and cataloging from the scene. 2,712 galaxy clusters that had been captured on the In my 8-inch reflector, NGC 1316 appears as a then-new National Geographic Society–Palomar bright, slightly oval disk with a distinctly brighter Observatory Sky Survey taken with the 48-inch Samuel nucleus. NGC 1317, about 12th magnitude and 2 ′ Oschin Schmidt camera at Palomar Observatory. In across, is visible in a 6-inch scope, although averted 1958, he published the results of his study as a paper vision may be needed to pick it out. -

Hubbles Spies the Beautiful Galaxy IC 335 24 December 2014

Hubbles spies the beautiful galaxy IC 335 24 December 2014 very low. Hence, the population of stars in S0 galaxies consists mainly of aging stars, very similar to the star population in elliptical galaxies. As S0 galaxies have only ill-defined spiral arms they are easily mistaken for elliptical galaxies if they are seen inclined face-on or edge-on as IC 335 here. And indeed, despite the morphological differences between S0 and elliptical class galaxies, they share some common characteristics, like typical sizes and spectral features. Both classes are also deemed "early-type" galaxies, because they are evolving passively. However, while elliptical galaxies may be passively evolving when we observe them, they have usually had violent interactions with other galaxies in their past. In contrast, S0 galaxies are either aging and Credit: ESA/Hubble and NASA fading spiral galaxies, which never had any interactions with other galaxies, or they are the aging result of a single merger between two spiral galaxies in the past. The exact nature of these This new NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope galaxies is still a matter of debate. image shows the galaxy IC 335 in front of a backdrop of distant galaxies. IC 335 is part of a galaxy group containing three other galaxies, and Provided by NASA located in the Fornax Galaxy Cluster 60 million light-years away. As seen in this image, the disk of IC 335 appears edge-on from the vantage point of Earth. This makes it harder for astronomers to classify it, as most of the characteristics of a galaxy's morphology—the arms of a spiral or the bar across the center—are only visible on its face. -

Mar / Apr 2017 1

Let’s see, does HGO’s roof roll off to the left or the right? If I didn’t know it would be difficult to tell! Even Stuart conceded the snow was too deep for observatory 2 Event Calendar—Main Events access. 3 SVAS Guest Speaker Schedule 4 Getting Acquainted with the SVAS Candidates 8 Seven Earth-Size Planets Around single Star! NASA I really enjoy beautiful winter scenes, and with HGO 10 Hubble Sees the Beautiful Galaxy IC335 and RJMO as the center piece, it couldn’t get any better! 11 SVAS ATM Connection 13 Solar Eclipse Provides Coronal Glimpse, Space Place 15 SVAS Main Events Looking forward to some great spring observing, 16 Classifieds 17 SVAS Officers, Board, Members , Application Observer Editor Mar / Apr 2017 1 March 17, Fri, SVAS Annual Election Meeting, 8:00pm. Sacramento City College, Mohr Hall Room 3, 3835 Freeport Boulevard, Sacramento, CA. There will be no speaker this month. March 25, Sat Blue Canyon, weather permitting. March 27, Monday New Moon. April 21 , Fri, SVAS General Meeting, 8:00pm. Sacramento City College, Mohr Hall Room 3, 3835 Freeport Boulevard, Sacramento, CA. April 22 & 29, Sat , Blue Canyon, weather permitting. Yes two dates this month! Let’s hope the snow clears. April 25, Tuesday New Moon. Mar 25 Apr 22 & 29 May 27 Jun 24 July 21-23 Star B Q Aug 19 Sept 16 & 23 Oct 21 Nov 18 Dec 16 Contact Wayne Lord Mar / Apr 2017 2 April 21, 2017, Bill Goff will discuss some of the types of variables, why amateur observations are important, opportu- nities for pro/am collaboration and some exciting recent develop- ments. -

Binocular Challenges

This page intentionally left blank Cosmic Challenge Listing more than 500 sky targets, both near and far, in 187 challenges, this observing guide will test novice astronomers and advanced veterans alike. Its unique mix of Solar System and deep-sky targets will have observers hunting for the Apollo lunar landing sites, searching for satellites orbiting the outermost planets, and exploring hundreds of star clusters, nebulae, distant galaxies, and quasars. Each target object is accompanied by a rating indicating how difficult the object is to find, an in-depth visual description, an illustration showing how the object realistically looks, and a detailed finder chart to help you find each challenge quickly and effectively. The guide introduces objects often overlooked in other observing guides and features targets visible in a variety of conditions, from the inner city to the dark countryside. Challenges are provided for viewing by the naked eye, through binoculars, to the largest backyard telescopes. Philip S. Harrington is the author of eight previous books for the amateur astronomer, including Touring the Universe through Binoculars, Star Ware, and Star Watch. He is also a contributing editor for Astronomy magazine, where he has authored the magazine’s monthly “Binocular Universe” column and “Phil Harrington’s Challenge Objects,” a quarterly online column on Astronomy.com. He is an Adjunct Professor at Dowling College and Suffolk County Community College, New York, where he teaches courses in stellar and planetary astronomy. Cosmic Challenge The Ultimate Observing List for Amateurs PHILIP S. HARRINGTON CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521899369 C P. -

A Galaxy Classification Grid That Better Recognises Early-Type Galaxy

MNRAS 000,1– ?? (2019) Preprint 24 July 2019 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 A galaxy classification grid that better recognises early-type galaxy morphology Alister W. Graham? Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122, Australia. Accepted 2019 June 7. Received 2019 June 7; in original form 2019 April 26 ABSTRACT A modified galaxy classification scheme for local galaxies is presented. It builds upon the Aitken-Jeans nebula sequence, by expanding the Jeans-Hubble tuning fork diagram, which it- self contained key ingredients from Curtis and Reynolds. The two-dimensional grid of galaxy morphological types presented here, with elements from de Vaucouleurs’ three-dimensional classification volume, has an increased emphasis on the often overlooked bars and continua of disc sizes in early-type galaxies — features not fully captured by past tuning forks, tridents, or combs. The grid encompasses nuclear discs in elliptical (E) galaxies, intermediate-scale discs in ellicular (ES) galaxies, and large-scale discs in lenticular (S0) galaxies, while the E4-E7 class is made redundant given that these galaxies are lenticular galaxies. Today, these struc- tures continue to be neglected, or surprise researchers, perhaps partly due to our indoctrination to galaxy morphology through the tuning fork diagram. To better understand the current and proposed classification schemes — whose origins reside in solar/planetary formation models — a holistic overview is given. This provides due credit to some of the lesser known pioneers, presents some rationale for the grid, and reveals the incremental nature of, and some of the lesser known connections in, the field of galaxy morphology. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Copyright© 2021 TCAA 1 All Rights Reserved Vol

Peculiar galaxies Hoag’s object: Here is a ring galaxy. Unique and beautiful. Inside the ring at 1:00 and far in the distance is a second ring galaxy. Peculiar isn’t it? TCAA Treasurer’s Report as of Image Credit: NASA, R. Lucas (STScI/AURA) July 27, 2021 By Sandullah Epsicokhan Here is a picture of a ring galaxy. This is an unusual object that does not fit the usual galactic form. As human beings, we tried to see patterns in things that we observe. Originally galaxies were classified based on how they looked. Exactly what classification does a galaxy like this fall into? We often talk about Edwin Hubble and how he came up with the discovery of galaxies outside of the Milky Way and a basic classification of galaxies. But it is the case, as it is in many cases, that discovery was a combination of factors. Some of the most important people behind the scenes that led up to this groundbreaking concept remain in the shadows of Dr. Hubble. Additionally, we have learned more about how peculiar galaxies are formed. Also, visit the North Visit Astronomical League Central Region of the at www.astroleague.org/ Astronomical League for more information (NCRAL) website at about the League and ncral.wordpress.com its numerous member for information about benefits and observing our North Central programs. Region and the status of our regional activities. Copyright© 2021 TCAA 1 All rights Reserved Vol. 46, No. 8 The OBSERVER Twin City Amateur Astronomers The OBSERVER is the monthly electronic newsletter of President’s note Twin City Amateur Astronomers, Inc., a registered 501(c)(3) non-profit educational By Tim Stone organization of amateur astronomers interested in studying astronomy and With another death in my family and a flooded basement sharing their hobby with the public. -

Globular Cluster Populations : First Results from S4G Early-Type Galaxies

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Faculty Scholarship 2-2015 Globular cluster populations : first esultsr from S4G early-type galaxies. Dennis Zaritsky University of Arizona Manuel Aravena Universidad Diego Portales E. Athanassoula Aix Marseille Universite Albert Bosma Aix Marseille Universite Sebastien Comeron University of Oulu See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/faculty Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons Original Publication Information Zaritsky, Dennis, et al. "Globular Cluster Populations: First Results from S4G Early-Type Galaxies." 2015. The Astrophysical Journal 799(2): 19 pp. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Dennis Zaritsky, Manuel Aravena, E. Athanassoula, Albert Bosma, Sebastien Comeron, Bruce G. Elmegreen, Santiago Erroz-Ferrer, Dimitri A. Gadotti, Joannah Hinz, Luis C. Ho, Benne W. Holwerda, Johan H. Knapen, Jarkko Laine, Eija Laurikainen, Juan Carlos Munoz-Mateos, Heikki Salo, and Kartik Sheth This article is available at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/ faculty/192 The Astrophysical Journal, 799:159 (19pp), 2015 February 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/799/2/159 C 2015. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. GLOBULAR CLUSTER POPULATIONS: FIRST RESULTS FROM S4G EARLY-TYPE GALAXIES Dennis Zaritsky1, Manuel Aravena2, E. Athanassoula3, Albert Bosma3,Sebastien´ Comeron´ 4,5, Bruce G. -

Volume 58, No 3, 2019 September the JOURNAL of the ROYAL

Southern Stars THE JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND Volume 58, No 3, 2019 September ISSN Page0049-1640 1 Southern Stars Journal of the RASNZ Royal Astronomical Society Volume 58, Number 3 of New Zealand (Inc.) 2019 September Founded in 1920 as the New Zealand Astronomical Society and assumed its present title on receiving the Royal Charter in 1946. In 1967 it became a member body of the R oyal Society of New Zealand. CONTENTS P O Box 3181, Wellington 6140, New Zealand Rakiura International Dark Sky Sanctuary [email protected] http://www.rasnz.org.nz R W Evans .............................................................. 3 Subscriptions (NZ$) for 2019: Ordinary member: $40.00 Fornax Galaxy Cluster Andrew Robertson .................................................. 5 Student member: $20.00 Affiliated society: $3.75 per member. th Minimum $75.00, Maximum $375.00 E.E. Barnard A Legendary 18-19 Century Corporate member: $200.00 Astrophotographer Whose Images Still ‘Wow’ Us.. John Drummond ..................................................... 8 Printed copies of Southern Stars (NZ$): $35.00 (NZ) A New Hope R W Evans ............................................................. 23 $45.00 (Australia & South Pacific) $50.00 (Rest of World) Book Review Grahame Fraser ................................................... 25 Council & Officers 2018 to 2020 FRONT COVER President: The barred spiral galaxy NGC 1365 in the Fornax Galaxy Nicholas Rattenbury Auckland. [email protected] Cluster Image: Steve Chadwick Immediate Past President: John Drummond Patutahi. [email protected] BACK COVER The galaxies NGC 1317 (the smaller one) and the Vice President: brightest member NGC 1316 also known as Fornax A, Steve Butler Invercargill. [email protected] on the edge of the Fornax Galaxy Cluster. -

A Prediction About the Age of Thick Discs As a Function of the Stellar Mass of the Host Galaxy S

A&A 645, L13 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202040175 & c ESO 2021 Astrophysics LETTER TO THE EDITOR A prediction about the age of thick discs as a function of the stellar mass of the host galaxy S. Comerón1,2 1 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain Received 18 December 2020 / Accepted 12 January 2021 ABSTRACT One of the suggested thick disc formation mechanisms is that they were born quickly and in situ from a turbulent clumpy disc. Subsequently, thin discs formed slowly within them from leftovers of the turbulent phase and from material accreted through cold flows and minor mergers. In this Letter, I propose an observational test to verify this hypothesis. By combining thick disc and total stellar masses of edge-on galaxies with galaxy stellar mass functions calculated in the redshift range of z ≤ 3:0, I derived a positive correlation between the age of the youngest stars in thick discs and the stellar mass of the host galaxy; galaxies with a present-day 10 stellar mass of M?(z = 0) < 10 M have thick disc stars as young as 4−6 Gyr, whereas the youngest stars in the thick discs of Milky-Way-like galaxies are ∼10 Gyr old. I tested this prediction against the scarcely available thick disc age estimates, all of them 10 are from galaxies with M?(z = 0) & 10 M , and I find that field spiral galaxies seem to follow the expectation. -

Box-And Peanut-Shaped Bulges: I. Statistics

A&A manuscript no. ASTRONOMY (will be inserted by hand later) AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 11 (11.05.2; 11.19.2; 11.19.7; 11.19.6) November 9, 2018 Box- and peanut-shaped bulges ⋆ I. Statistics R. L¨utticke, R.-J. Dettmar, and M. Pohlen Astronomisches Institut, Ruhr-Universit¨at Bochum, D-44780 Bochum, Germany email: [email protected] Received 11 May 2000; accepted 14 June 2000 Abstract. We present a classification for bulges of a com- External cylindrically symmetric torques (May et al. plete sample of ∼ 1350 edge-on disk galaxies derived from 1985) or mergers of two disk galaxies (Binney & Petrou the RC3 (Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies, 1985, Rowley 1988) as origins of b/p bulges require very de Vaucouleurs et al. 1991). A visual classification of the special conditions (Bureau 1998). Therefore such evolu- bulges using the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) in three types tionary scenarios can explain only a very low frequency of of b/p bulges or as an elliptical type is presented and sup- b/p bulges. Accretion of satellite galaxies is a formation ported by CCD images. NIR observations reveal that dust process of b/p bulges (Binney & Petrou 1985, Whitmore & extinction does almost not influence the shape of bulges. Bell 1988), which could produce a higher frequency of b/p There is no substantial difference between the shape of bulges. However, an oblique impact angle of the satellite bulges in the optical and in the NIR. Our analysis reveals is needed for the formation of a b/p bulge and a mas- that 45% of all bulges are box- and peanut-shaped (b/p). -

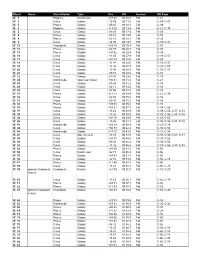

HB-NGC Index

Object Name Constellation Type Dec RA Season HB Page IC 1 Pegasus Double star +27 43 00 08.4 Fall C-21 IC 2 Cetus Galaxy -12 49 00 11.0 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 3 Pisces Galaxy -00 25 00 12.1 Fall C-39 IC 4 Pegasus Galaxy +17 29 00 13.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 5 Cetus Galaxy -09 33 00 17.4 Fall C-39 IC 6 Pisces Galaxy -03 16 00 19.0 Fall C-39 IC 8 Pisces Galaxy -03 13 00 19.1 Fall C-39 IC 9 Cetus Galaxy -14 07 00 19.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 10 Cassiopeia Galaxy +59 18 00 20.4 Fall C-03 IC 12 Pisces Galaxy -02 39 00 20.3 Fall C-39 IC 13 Pisces Galaxy +07 42 00 20.4 Fall C-39 IC 16 Cetus Galaxy -13 05 00 27.9 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 17 Cetus Galaxy +02 39 00 28.5 Fall C-39 IC 18 Cetus Galaxy -11 34 00 28.6 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 19 Cetus Galaxy -11 38 00 28.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 20 Cetus Galaxy -13 00 00 28.5 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 21 Cetus Galaxy -00 10 00 29.2 Fall C-39 IC 22 Cetus Galaxy -09 03 00 29.6 Fall C-39 IC 24 Andromeda Open star cluster +30 51 00 31.2 Fall C-21 IC 25 Cetus Galaxy -00 24 00 31.2 Fall C-39 IC 29 Cetus Galaxy -02 11 00 34.2 Fall C-39 IC 30 Cetus Galaxy -02 05 00 34.3 Fall C-39 IC 31 Pisces Galaxy +12 17 00 34.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 32 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.0 Fall C-39 IC 33 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.1 Fall C-39 IC 34 Pisces Galaxy +09 08 00 35.6 Fall C-39 IC 35 Pisces Galaxy +10 21 00 37.7 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 37 Cetus Galaxy -15 23 00 38.5 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 38 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 38.6 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 40 Cetus Galaxy +02 26 00 39.5 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 42 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 41.1 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC