1 INSIDE CHURNALISM PR, Journalism and Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pity the Poor Citizen Complainant

ADVICE, INFORMATION. RESEARCH & TRAINING ON MEDIA ETHICS „Press freedom is a responsibility exercised by journalists on behalf of the public‟ PITY THE POOR CITIZEN COMPLAINANT Formal statement of evidence to The Leveson Inquiry into the Culture, Practice & Ethics of the Press The MediaWise Trust University of the West of England, Bristol BS16 2JP 0117 93 99 333 www.mediawise.org.uk Documents previously submitted i. Freedom and Responsibility of the Press: Report of Special Parliamentary Hearings (M Jempson, Crantock Communications, 1993) ii. Stop the Rot, (MediaWise submission to Culture, Media & Sport Select Committee hearings on privacy, 2003) iii. Satisfaction Guaranteed? Press complaints systems under scrutiny (R Cookson & M Jempson (eds.), PressWise, 2004) iv. The RAM Report: Campaigning for fair and accurate coverage of refugees and asylum-seekers (MediaWise, 2005) v. Getting it Right for Now (MediaWise submission to PCC review, 2010) vi. Mapping Media Accountability - in Europe and Beyond (Fengler et al (eds.), Herbert von Halem, 2011) The MediaWise Trust evidence to the Leveson Inquiry PITY THE POOR CITIZEN COMPLAINANT CONTENTS 1. The MediaWise Trust: Origins, purpose & activities p.3 2. Working with complainants p.7 3. Third party complaints p.13 4. Press misbehaviour p.24 5. Cheque-book journalism, copyright and photographs p.31 6. ‗Self-regulation‘, the ‗conscience clause‘, the Press Complaints Commission and the Right of Reply p.44 7. Regulating for the future p.53 8. Corporate social responsibility p.59 APPENDICES pp.61-76 1. Trustees, Patrons & Funders p.61 2. Clients & partners p.62 3. Publications p.64 4. Guidelines on health, children & suicide p.65 5. -

The Perceived Credibility of Professional Photojournalism Compared to User-Generated Content Among American News Media Audiences

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2020 THE PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY OF PROFESSIONAL PHOTOJOURNALISM COMPARED TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT AMONG AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA AUDIENCES Gina Gayle Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gayle, Gina, "THE PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY OF PROFESSIONAL PHOTOJOURNALISM COMPARED TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT AMONG AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA AUDIENCES" (2020). Dissertations - ALL. 1212. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1212 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This study examines the perceived credibility of professional photojournalism in context to the usage of User-Generated Content (UGC) when compared across digital news and social media platforms, by individual news consumers in the United States employing a Q methodology experiment. The literature review studies source credibility as the theoretical framework through which to begin; however, using an inductive design, the data may indicate additional patterns and themes. Credibility as a news concept has been studied in terms of print media, broadcast and cable television, social media, and inline news, both individually and between genres. Very few studies involve audience perceptions of credibility, and even fewer are concerned with visual images. Using online Q methodology software, this experiment was given to 100 random participants who sorted a total of 40 images labeled with photographer and platform information. The data revealed that audiences do discern the source of the image, in both the platform and the photographer, but also take into consideration the category of news image in their perception of the credibility of an image. -

How Relevance Works for News Audiences

DIGITAL NEWS PROJECT FEBRUARY 2019 What do News Readers Really Want to Read about? How Relevance Works for News Audiences Kim Christian Schrøder Contents About the Author 4 Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 7 1. Recent Research on News Preferences 8 2. A Bottom-Up Approach 10 3. Results: How Relevance Works for News Audiences 12 4. Results: Four News Content Repertoires 17 5. Results: Shared News Interests across Repertoires 23 6. Conclusion 26 Appendix A: News Story Cards and their Sources 27 Appendix B: Fieldwork Participants 30 References 31 THE REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM About the Author Kim Christian Schrøder is Professor of Communication at Roskilde University, Denmark. He was Google Digital News Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism January–July 2018. His books in English include Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity (co-edited, 2014), The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Media, and Communication (co-edited 2019) and Researching Audiences (co-authored, 2003). His research interests comprise the analysis of audience uses and experiences of media. His recent work explores mixed methods for mapping news consumption. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the Reuters Institute’s research team for their constructive comments and practical help during the planning of the fieldwork, and for their feedback to a draft version of this report. In addition to Lucas Graves, whose assistance in editing the manuscript was invaluable, I wish to thank Nic Newman, Richard Fletcher, Joy Jenkins, Sílvia Majó-Vázquez, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, Alessio Cornia, and Annika Sehl. -

Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame Induction Program, Oct. 17, Washington, Mo

September 2013 Geri Migielicz Missouri Newspaper Hall of Fame will induct 5 during the MPA Con- 7 vention in Kansas City. Bob Linder Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame Induction Program, Oct. 17, Washington, Mo. Foundation work com- 4 pleted on MPA building 5 in Columbia. Jim Miller Jr. Regular Features President 2 Scrapbook 12 On the Move 10 NIE Report 15 Obituaries 11 Jean Maneke 17 Missouri Press News, September 2013 www.mopress.com Digital Footprint a powerful new tool! Your advertisers want, need online presence ery soon you’re going to start hearing more about stated by Nienhueser. Digital Footprint, the Missouri Press Service’s name “Another goal of this program will be to enhance the rela- Vfor a new package of services you’ll be able to offer to tionship between Missouri Press Service and the newspapers,” local businesses. You will hear a little about Digital Footprint he said. “With better and more frequent promotion of MPS at the MPA Convention in Kansas City. products, we can’t help but generate more revenue Missouri Press will promote Digital Foot- for everyone. We think the newspapers will ap- print to its member newspapers and to po- preciate that.” tential users of the services around the state To help implement this program, the Missouri and country. We’re going to provide member Press board approved the hiring of another sales newspapers with material they can use to pro- person and a graphic designer. Patton, mentioned mote these services in their markets. above, is the designer; the sales person might be We’ve got a new graphics designer, Jeremy on staff by the time you read this. -

A Comparative Analysis on News Values: Comparing Coverage of Education in South Korea and the United States✝

Korean Social Science Journal 2011, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 99~132 Comparative Review A Comparative Analysis on News Values: Comparing Coverage of Education in South Korea and the United States✝ Jae Chul Shim* (Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Korea University) Wan Kyu Jung** (Lecturer, Division of Political Science, Public Administration and Journalism, Wonkwang University) Kyun Soo Kim*** (Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication, Grambling State University) Abstract This study investigates how Korean major dailies covered educational issues regarding universities, and compares its findings with those of leading American newspapers. The results show that Korean newspapers covered the universities much more negatively than their American counterparts did. Korean newspapers also demonstrated lower journalistic standards as compared with the American newspapers. There were some gaps in terms of news values in covering education at the college level between Korean and American newspapers. Nevertheless, these professional gaps were not too wide to be bridged. In addition, Ettema and Glasser’s three new news values of investigative reporting were not unique from the traditional ones in this study. They were mixed with those of fairness and professional reporting. From these findings, we discuss typical characteristics of Korean newspaper coverage and suggest new ways of covering the education beats in South Korea as a newly advanced and democratized country. Key words: Educational Reform, News Values, Comparative Journalistic Standards, Education Reporting, University News, Diversity, New Long Journalism 100 … Jae Chul Shim, Wan Kyu Jung, and Kyun Soo Kim ✝ This paper was originally written in Korean and published in The Korean Journal of Journalism and Communication Studies in 2003. -

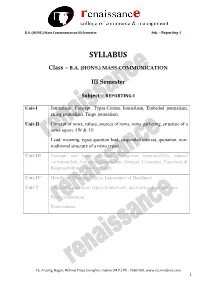

Class – BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION III Semester

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication III Semester Sub. – Reporting-I SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION III Semester Subject – REPORTING-I Unit-I Journalism: Concept, Types-Citizen Journalism, Embeded journalism, string journalism, Tingo journalism. Unit-II Concept of news, values, sources of news, news-gathering, structure of a news report. 5W & 1H Lead: meaning, types question lead, suspended interest, quotation, non- traditional structure of a news report. Unit-III Concept and kinds of beat. Categories reporters-City, special correspondent, foreign correspondent, Stringer, Columnist, Functions & Responsibilities, follow-up story. Unit-IV Headlines: Meaning, Types, Importance of Headlines. Unit-V What is an interview, types of interview, interviewer & its qualities. Press conferences. Press release. 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication III Semester Sub. – Reporting-I UNIT-I & II JOURNALISM - INTRODUCTION Journalism is the practice of investigating and reporting events, issues and trends to the mass audiences of print, broadcast and online media such as newspapers, magazines and books, radio and television stations and networks, and blogs and social and mobile media. The product generated by such activity is called journalism. People who gather and package news and information for mass dissemination are journalists. The field includes writing, editing, design and photography. With the idea in mind of informing the citizenry, journalists cover individuals, organizations, institutions, governments and businesses as well as cultural aspects of society such as arts and entertainment. News media are the main purveyors of information and opinion about public affairs. WHAT DOES A JOURNALIST DO? The main intention of those working in the journalism profession is to provide their readers and audiences with accurate, reliable information they need to function in society. -

Thesis Old Media, New Media

THESIS OLD MEDIA, NEW MEDIA: IS THE NEWS RELEASE DEAD YET? HOW SOCIAL MEDIA ARE CHANGING THE WAY WILDFIRE INFORMATION IS BEING SHARED Submitted By Mary Ann Chambers Department of Journalism and Technical Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2015 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Joseph Champ Peter Seel Tony Cheng Copyright by Mary Ann Chambers 2015 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT OLD MEDIA, NEW MEDIA: IS THE NEWS RELEASE DEAD YET? HOW SOCIAL MEDIA ARE CHANGING THE WAY WILDFIRE INFORMATION IS BEING SHARED This qualitative study examines the use of news releases and social media by public information officers (PIO) who work on wildfire responses, and journalists who cover wildfires. It also checks in with firefighters who may be (unknowingly or knowingly) contributing content to the media through their use of social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook. Though social media is extremely popular and used by all groups interviewed, some of its content is unverifiable ( Ma, Lee, & Goh, 2014). More conventional ways of doing business, such as the news release, are filling in the gaps created by the lack of trust on the internet and social media sites and could be why the news release is not dead yet. The roles training, friends, and colleagues play in the adaptation of social media as a source is explored. For the practitioner, there are updates explaining what social media tools are most helpful to each group. For the theoretician, there is news about changes in agenda building and agenda setting theories caused by the use of social media. -

Beyond Objectivity and Relativism: a View Of

BEYOND OBJECTIVITY AND RELATIVISM: A VIEW OF JOURNALISM FROM A RHETORICAL PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Catherine Meienberg Gynn, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1995 Dissertation Committee Approved by Josina M. Makau Susan L. Kline Adviser Paul V. Peterson Department of Communication Joseph M. Foley UMI Number: 9533982 UMI Microform 9533982 Copyright 1995, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 DEDICATION To my husband, Jack D. Gynn, and my son, Matthew M. Gynn. With thanks to my parents, Alyce W. Meienberg and the late John T. Meienberg. This dissertation is in respectful memory of Lauren Rudolph Michael James Nole Celina Shribbs Riley Detwiler young victims of the events described herein. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I express sincere appreciation to Professor Josina M. Makau, Academic Planner, California State University at Monterey Bay, whose faith in this project was unwavering and who continually inspired me throughout my graduate studies, and to Professor Susan Kline, Department of Communication, The Ohio State University, whose guidance, friendship and encouragement made the final steps of this particular journey enjoyable. I wish to thank Professor Emeritus Paul V. Peterson, School of Journalism, The Ohio State University, for guidance that I have relied on since my undergraduate and master's programs, and whose distinguished participation in this project is meaningful to me beyond its significant academic merit. -

Subsidizing the News? Organizational Press Releases' Influence on News Media's Agenda and Content Boumans, J

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Subsidizing the news? Organizational press releases' influence on news media's agenda and content Boumans, J. DOI 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1338154 Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Journalism Studies License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Boumans, J. (2018). Subsidizing the news? Organizational press releases' influence on news media's agenda and content. Journalism Studies, 19(15), 2264-2282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1338154 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 SUBSIDIZING THE NEWS? Organizational press releases’ influence on news media’s agenda and content Jelle Boumans The relation between organizational press releases and newspaper content has generated consider- able attention. -

CHANGING JOURNALISM for the LIKELY PRESENT Abstract

CHANGING JOURNALISM FOR THE LIKELY PRESENT S T E P H E N Q U I N N , P H D (Refereed) Associate Professor of Journalism Deakin University Victoria Abstract Media convergence and newsroom integration have become industry buzzwords as the ideas spread through newsrooms around the world. In November 2007 Fairfax Media in Australia introduced the newsroom of the future model, as its flagship newspapers moved into a purpose-built newsroom in Sydney. News Ltd, the country’s next biggest media group, is also embracing multi-media forms of reporting. What are the implications of this development for journalism? This paper examines changes in the practice of journalism in Australia and around the world. It attempts to answer the question: How does the practice of journalism need to change to prepare not for the future, but for the likely present. early in November 2007 The Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Financial Review and the Sun-Herald moved into a new building dubbed the ‘newsroom of the future’ at One Darling Island Road in Sydney’s Darling Harbour precinct. Phil McLean, at the time Fairfax Media’s group executive editor and the man in charge of the move, said three quarters of the entire process involved getting people to ‘think differently’ – that is, to modify their mindset so they could work with multi-media. The new newsroom symbolised the culmination of a series of major changes at Fairfax. In August 2006 the traditional newspaper company, John Fairfax Ltd, changed its name to Fairfax Media to reflect its multi-platform future. -

Print Journalism: a Critical Introduction

Print Journalism A critical introduction Print Journalism: A critical introduction provides a unique and thorough insight into the skills required to work within the newspaper, magazine and online journalism industries. Among the many highlighted are: sourcing the news interviewing sub-editing feature writing and editing reviewing designing pages pitching features In addition, separate chapters focus on ethics, reporting courts, covering politics and copyright whilst others look at the history of newspapers and magazines, the structure of the UK print industry (including its financial organisation) and the development of journalism education in the UK, helping to place the coverage of skills within a broader, critical context. All contributors are experienced practising journalists as well as journalism educators from a broad range of UK universities. Contributors: Rod Allen, Peter Cole, Martin Conboy, Chris Frost, Tony Harcup, Tim Holmes, Susan Jones, Richard Keeble, Sarah Niblock, Richard Orange, Iain Stevenson, Neil Thurman, Jane Taylor and Sharon Wheeler. Richard Keeble is Professor of Journalism at Lincoln University and former director of undergraduate studies in the Journalism Department at City University, London. He is the author of Ethics for Journalists (2001) and The Newspapers Handbook, now in its fourth edition (2005). Print Journalism A critical introduction Edited by Richard Keeble First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX9 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Selection and editorial matter © 2005 Richard Keeble; individual chapters © 2005 the contributors All rights reserved. -

News Values and Newsworthiness

News Values and Newsworthiness Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication News Values and Newsworthiness Helen Caple Subject: Journalism Studies Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.850 Summary and Keywords How events become news has always been a fundamental question for both journalism practitioners and scholars. For journalism practitioners, news judgments are wrapped up in the moral obligation to hold the powerful to account and to provide the public with the means to participate in democratic governance. For journalism scholars, news selection and construction are wrapped up in investigations of news values and newsworthiness. Scholarship systematically analyzing the processes behind these judgments and selections emerged in the 1960s, and since then, news values research has made a significant contribution to the journalism literature. Assertions have been made regarding the status of news values, including whether they are culture bound or universal, core or standard. Some hold that news values exist in the minds of journalists or are even metaphorically speaking “part of the furniture,” while others see them as being inherent or infused in the events that happen or as discursively constructed through the verbal and visual resources deployed in news storytelling. Like in many other areas of journalism research, systematic analysis of the role that visuals play in the construction of newsworthiness has been neglected. However, recent additions to the scholarship on visual news values analysis have begun to address this shortfall. The convergence and digitization of news production, rolling deadlines, new media platforms, and increasingly active audiences have also impacted on how news values research is conducted and theorized, making this a vibrant and ever-evolving research paradigm.