Nahal Ghoghaie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S Q U a L L I a B S C H Reservation Nisqually Market to Expand

S q u a l l i A b s c h NewsNisqually Tribal News 4820 She-Nah-Num Dr. SE Olympia, WA 98513 Phone Number (360)456-5221 Volume 8, Issue 1 www.nisqually-nsn.gov January 2018 Reservation Nisqually Market to Expand By Debbie Preston The Nisqually Tribe’s reservation Nisqually Market will expand with a $3.5 million, 10,000-square-foot building in the new year, according to Bob Iyall, Medicine Creek Enterprise Corporation Chief Executive Officer. “The phase two was always in the original plans for the market,” Iyall said. The new addition will not affect the operations of the current store except for a minor change in the entrance to the drive-in during construction. The expansion will include offices for the Nisqually Construction Company on the second floor and a mixture of retail on the ground floor. “We are going to have a mail shop, kind of like a UPS store, but we’re going to run it,” Iyall said. Other tenants are still being decided, but will probably include some sort of fast food business. The Nisqually Construction Company will build the project and that will include four to five tribal member jobs through TERO. Meanwhile, the Frederickson store that opened in the fall of 2017 is doing quite well. “In that location, we are serving a number of companies that have 24-hour operations such as Boeing and JBLM. We’re already selling twice as much gas there as we do at our reservation store.” Additionally, the deli is in high demand due to the shift workers. -

Nisqually Transmission Line Relocation Project

Nisqually Transmission Line Relocation Project Preliminary Environmental Assessment Bonneville Power Administration Fort Lewis Military Reservation Nisqually Indian Tribe Bureau of Indian Affairs October 2004 Nisqually Transmission Line Relocation Project Responsible Agencies and Tribe: U.S. Department of Energy, Bonneville Power Administration (Bonneville); U.S. Department of Defense, Fort Lewis Military Reservation (Fort Lewis); the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA); and the Nisqually Indian Tribe (Tribe). Name of Proposed Project: Nisqually Transmission Line Relocation Project Abstract: Bonneville proposes to remove and reroute two parallel transmission lines that cross the Nisqually Indian Reservation in Thurston County, Washington. Bonneville’s easement across the Reservation for a portion of the Olympia-Grand Coulee line has expired. Though Bonneville has a perpetual easement for the Olympia-South Tacoma line across the Reservation, the Tribe has asked Bonneville to remove both lines so the Tribe can eventually develop the land for its community. The land fronts State Route 510 and is across the highway from the Tribe’s Red Wind Casino. In addition, the Tribe would like Bonneville to remove the two lines from a parcel next to the Reservation that Fort Lewis owns. The Tribe is working with Fort Lewis to obtain this parcel, which also has frontage on SR 510. Bonneville is proposing to remove the portions of these lines on the Reservation and on the Fort-owned parcel and rebuild them south of SR 510 on Fort Lewis property. Fort Lewis is willing to have these lines on their federal property, in exchange for other in-holdings currently owned by Thurston County that the Tribe would purchase and turn over to Fort Lewis. -

Nisqually State Park Interpretive Plan

NISQUALLY STATE PARK INTERPRETIVE PLAN OCTOBER 2020 Prepared for the Nisqually Indian Tribe by Historical Research Associates, Inc. We acknowledge that Nisqually State Park is part of the homelands of the Squalli-absch (sqʷaliʔabš) people. We offer respect for their history and culture, and for the path they show in caring for this place. “All natural things are our brothers and sisters, they have things to teach us, if we are aware and listen.” —Willie Frank, Sr. Nisqually State Park forest. Credit: HRA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 5 PART 1: FOUNDATION. .11 Purpose and Guiding Principles . .12 Interpretive Goals . 12 Desired Outcomes . .13 Themes. 14 Setting and Connections to Regional Interpretive Sites . 16 Issues and Influences Affecting Interpretation . .18 PART 2: RECOMMENDATIONS . .21 Introduction . 22 Recommended Approach . .22 Recommended Actions and Benchmarks . 26 Interpretive Media Recommendations . 31 Fixed Media Interpretation . .31 Digital Interpretation . 31 Personal Services . 32 Summary . 33 PLANNING RESOURCES . 34 HRA Project Team . 35 Interpretive Planning Advisory Group and Planning Meeting Participants . .35 Acknowledgements . 35 Definitions . 35 Select Interpretation Resources. 36 Select Management Documents . 36 Select Topical Resources. 36 APPENDICES Appendix A: Interpretive Theme Matrix Appendix B: Recommended Implementation Plan Appendix C: Visitor Experience Mapping INTRODUCTION Nisqually State Park welcome sign includes Nisqually design elements and Lushootseed language translation. Credit: HRA Nisqually State Park | Interpretive Plan | October 2020 5 The Nisqually River is a defining feature of Nisqually State Park. According to the late Nisqually historian Cecelia Svinth Carpenter, “The Nisqually River became the thread woven through the heart and fabric of the Nisqually Indian people.” —Carpenter, The Nisqually People, My People. -

The Trials of Leschi, Nisqually Chief

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 14 11-1-2006 The Trials of Leschi, Nisqually Chief Kelly Kunsch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Recommended Citation Kunsch, Kelly (2006) "The Trials of Leschi, Nisqually Chief," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol5/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 67 The Trials of Leschi, Nisqually Chief Kelly Kunsch1 His people’s bitterness is etched into stone: A MEMORIAL TO CHIEF LESCHI 1808-1858 AN ARBITRATOR OF HIS PEOPLE JUDICIALLY MURDERED, FEBRUARY 19, 18582 There is probably no one convicted of murder more beloved by his people than a man named Leschi. Among other things, he has a neighborhood in Seattle, Washington named after him, a city park, a marina, restaurants and stores, as well as a school on the Puyallup Indian Reservation. His name is revered by Northwest Indians and respected by non-Indians who know his story. And yet, he remains, legally, a convicted murderer. For years there has been a small movement to clear Leschi’s name. However, it was only two years ago, almost 150 years after his conviction, that -

Thank You Garden Staff!

S q u a l l i A b s c h NewsNisqually Tribal News 4820 She-Nah-Num Dr. SE Olympia, WA 98513 Phone Number (360)456-5221 Volume 9, Issue 10 www.nisqually-nsn.gov November 2019 10 Years of the Nisqually Community Garden By Chantay Anderson, Janell Blacketer, Carlin Briner and Grace Ann Byrd The Nisqually Community Garden celebrated 10 years this summer and we wrapped up another successful season with the annual Harvest Party on October 15th, 2019. The event was well attended and featured a seasonal dinner, cider pressing with the apples from the Garden, and an abundant giveaway of food and medicine. We would like to give a big thanks to our volunteers, the Youth Center staff, and our garden staff, especially our extraordinary seasonal crew as they are finishing up their work for the year. As we continually gather community feedback, our programing has grown and evolved over the years. In the past couple years we have increased services to Nisqually Elders. This year we completed our second season of the Elders Home Delivery program – this year 24 Nisqually Elders received a box of assorted produce from the Garden each week through the peak season. Also, in collaboration with the Nisqually AmeriCorps crew, we built raised garden beds in the yards of 5 Elders and provided seeds and starts for their own gardens. We will continue to build raised garden beds for 5 Elders each spring. In addition to increasing services to Elders, we have also expanded our nutrition education and medicinal plant program over the past several years. -

Congratulation Newly Elected Officials! May 6Th, 2021 Nisqually Tribe's Newly Elected Tribal Council Chairman, Willie Frank Jr

Nisqually Indian Tribe Squalli Absch NewsNisqually Tribal News 4820 She-Nah-Num Dr. SE Olympia, WA 98513 Phone # 360-456-5221 Volume 11 Issue 6 www.nisqually-nsn.gov June 2021 Congratulation Newly Elected Officials! May 6th, 2021 Nisqually Tribe's newly elected Tribal Council Chairman, Willie Frank Jr. Secretary, Jackie Whittington and 5th Council, Chay Squally. Sargeant of Arms, Derrick Sanchez. Enrollment Sophie Johns, Kahelelani Kalama, Andrew Squally and Shareholder Maury Sanchez. How to Contact Us Tribal Estate and Will Planning Tribal Center 360-456-5221 Tribal Estate Planning Services provided by Emily Penoyar- Health Clinic 360-459-5312 Rambo Law Enforcement 360-459-9603 Youth Center 360-455-5213 Services offered: Natural Resources 360-438-8687 � Last will and testament � Durable power of attorney � Healthcare directive Nisqually Tribal News � Tangible personal property bequest 4820 She-Nah-Num Dr. SE � Funeral/burial instructions Olympia, WA 98513 � Probate 360-456-5221 Zoom meetings will be set up for the first and third Thursday of Leslee Youckton each month. Available appointment times are 8:30 a.m., 9:30 a.m., [email protected] 10:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. ext. 1252 Please call Lori Lehman at 360-456-5221 to set up an The deadline for the newsletter is appointment. the second Monday of every month. Nisqually Tribal Council NON-EMERGENCY # Chair, William (Willie) Frank III Vice Chair, Antonette Squally Secretary, Jackie Whittington 360-412-3030 Treasurer, David Iyall Call this number to leave a 5th Council, Chaynannah (Chay) Squally 6th Council, Hanford McCloud NON-EMERGENCY crime tip. -

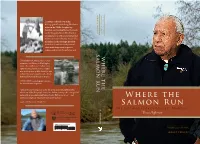

Where the Salmon Run: the Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr

LEGACY PROJECT A century-old feud over tribal fishing ignited brawls along Northwest rivers in the 1960s. Roughed up, belittled, and handcuffed on the banks of the Nisqually River, Billy Frank Jr. emerged as one of the most influential Indians in modern history. Inspired by his father and his heritage, the elder united rivals and survived personal trials in his long career to protect salmon and restore the environment. Courtesy Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission salmon run salmon salmon run salmon where the where the “I hope this book finds a place in every classroom and library in Washington State. The conflicts over Indian treaty rights produced a true warrior/states- man in the person of Billy Frank Jr., who endured personal tragedies and setbacks that would have destroyed most of us.” TOM KEEFE, former legislative director for Senator Warren Magnuson Courtesy Hank Adams collection “This is the fascinating story of the life of my dear friend, Billy Frank, who is one of the first people I met from Indian Country. He is recognized nationally as an outstanding Indian leader. Billy is a warrior—and continues to fight for the preservation of the salmon.” w here the Senator DANIEL K. INOUYE s almon r un heffernan the life and legacy of billy frank jr. Trova Heffernan University of Washington Press Seattle and London ISBN 978-0-295-99178-8 909 0 000 0 0 9 7 8 0 2 9 5 9 9 1 7 8 8 Courtesy Michael Harris 9 780295 991788 LEGACY PROJECT Where the Salmon Run The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. -

Influential People| Page 1

Tribal History Resources for Educators | Influential People| Page 1 HistoryLink.org is the free online encyclopedia of Washington State history. To make it easier for you to fulfill the new state requirement to incorporate tribal history into K-12 social studies curricula, we have put together a set of resource lists identifying essays on HistoryLink that explore Washington’s tribal history. Click on the linked essay number, or enter the number in the search box on HistoryLink.org. HistoryLink’s content is produced by staff historians, freelance writers and historians, community experts, and supervised volunteers. All articles (except anecdotal “People’s History” essays) are fully sourced and 1411 4th Ave. Suite 804 carefully edited before posting and updated or revised when needed. These essays are just a sampling of Seattle, WA 98101 the tribal history available on HistoryLink. Search HistoryLInk to find more and check back often for new 206.447.8140 content. Arquette, William “Chief” (1884-1943). Musician and mem- Chirouse, Father Eugene Casimir (1821-1892) Missionary ber of the Puyallup Indian Tribe. Over a decades-long career of the Catholic Oblates of Mary Immaculate. Established a he played a number of different instruments in a number of school and church on the Tulalip Reservation and missions at bands and productions, including the United States Indian other locations. 9033 Band, Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, the John Philip Comcomly (1760s?-1830) Leader among the Chinook Indian Sousa Band, the Seattle Symphony, and others over a de- bands living along the lower Columbia River. Credited by many cades-long career. -

Nisqually Health Department Brings You CUTTING EDGE DISINFECTING with POWERFUL XENON LIGHT to ENHANCE PATIENT SAFETY

S q u a l l i A b s c h NewsNisqually Tribal News 4820 She-Nah-Num Dr. SE Olympia, WA 98513 Phone Number 360-456-5221 Volume 10 Issue 8 www.nisqually-nsn.gov October 2020 Nisqually Health Department brings you CUTTING EDGE DISINFECTING WITH POWERFUL XENON LIGHT TO ENHANCE PATIENT SAFETY LightStrike™, an intense Germ-Zapping™ UV Robot that quickly* disinfects and deactivates potentially harmful bacteria and viruses. LightStrike is a chemical-free, hospital grade, disinfection technology that helps reduce the spread of infections without causing materials damage. LightStrike is the FIRST UV disinfection technology proven to deactivate SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19) in 2 minutes!** Your Safety First: The Robot operates without people in the room and the Xenon light cannot penetrate doors, glass or plastic. * Cycle times vary based on room layout and size. ** 2 minute cycle times were validated for high touch surfaces at 1 meter. Frequently Asked Safety Questions What is LIGHTSTRIKE™? LightStrike is a UV disinfection Robot. The Robot uses a Pulsed Xenon lamp to create intense germicidal ultraviolet light that kills the germs that cause infections such as C. diff, MRSA, VRE and other pathogens. What is someone walks in while the robot is operating? The Robot is always operated in an unoccupied space. Although brief exposure to the light is not a threat, there are safety features on the Robot to prevent this: Continued on page 3-LIGHTSTRIKE How to Contact Us Tribal Estate and Will Planning Tribal Center (360) 456-5221 Tribal Estate Planning Services provided by Emily Penoyar- Health Clinic (360) 459-5312 Rambo Law Enforcement (360) 459-9603 Youth Center (360) 455-5213 Services offered: Natural Resources (360) 438-8687 � Last will and testament � Durable power of attorney � Healthcare directive Nisqually Tribal News � Tangible personal property bequest 4820 She-Nah-Num Dr. -

Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement Thurston and Pierce Counties, Washington

Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement Thurston and Pierce Counties, Washington Type of Action: Administrative Lead Agency: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service Responsible Official: David B. Allen, Regional Director For Further Information: Jean Takekawa, Refuge Manager Nisqually NWR Complex 100 Brown Farm Road Olympia, WA 98516 (360) 753-9467 Abstract: Four alternatives, including a Preferred Alternative and a No Action Alternative, are described, compared, and assessed for Nisqually NWR. Alternative A is the No Action Alternative, as required by the National Environmental Policy Act regulations. Selection of this alternative would mean that a Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) would be based on continuing management of the Refuge as it has been over the past several years. The four alternatives are summarized below: Alternative A—No Action: Status Quo – This alternative assumes no change from past management programs and is considered the base from which to compare the other alternatives. There would be no changes to the Refuge boundary and no major changes in habitat management or public use programs. Alternative B—Refuge Expansion of 2,407 Acres and Minimum Estuarine Restoration – This alternative would provide for moderate expansion of the Refuge boundary (2,407-acre addition). It places new management emphasis on the restoration of estuarine habitat and improved freshwater wetland management. The current environmental education program would be improved and expanded, to the largest degree of all action alternatives. There would be fewer changes to the trail system than in other action alternatives, and the Refuge would remain closed to waterfowl hunting, with the closure posted and enforced. -

What Happened to the Steh-Chass People?

Pat Rasmussen PO Box 13273 Olympia, WA 98508 Phone: 509-669-1549 E-mail: [email protected] November 23, 2014 What happened to the Steh-chass people? The Steh-chass people lived in a permanent village at the base of Tumwater Falls for thousands of years. The Steh-chass village was a permanent settlement – property and food were stored there. They lived in gabled cedar plank homes of rectangular, slightly slanted sides of cedar posts and planks. In the mid-1850’s there were three cedar plank homes there.1 A community of up to eight families lived in each with bed platforms along the walls. The village was a ceremonial site, a sacred site, where at least five tribes - the Nisqually, Squaxin, Chehalis, Suquamish and Duwamish - gathered for ceremonies, feasts, potlatches and to harvest and preserve salmon, clams, mussels, whelts, and moon snails, as well as crabs, barnacles, Chinese slippers, oysters and cockles, by drying, smoking or baking in rock-lined underground ovens.2 Layers of seashells recorded many years of habitation. The village was named Steh-chass and the river, now the Deschutes, was named Steh- chass River.3 The Steh-chass people, a sub-tribe of the Nisqually Indians, fished and gathered seafood all along the shores of Budd inlet.4 T. T. Waterman’s maps of Budd Inlet from the mid-1800’s show the Steh-chass Indians lived along the shores of the entire inlet.5 The Steh-chass people were led by Sno-ho-dum-set, known as a man of peace.6 At the Medicine Creek Treaty Council of December 24-26, 1854, Sno-ho-dum- set represented the -

Puyallup Indian Acculturation, Federal Indian Policy and the City of Tacoma, 1832-1909

The Promise and the Price of Contact: Puyallup Indian Acculturation, Federal Indian Policy and the City of Tacoma, 1832-1909 Kurt Kim Schaefer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Dr. John Findlay, Chair Dr. Alexandra Harmon Dr. Bruce Hevly Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History The Promise and the Price of Contact: Puyallup Indian Acculturation, Federal Indian Policy and the City of Tacoma, 1832-1909 Copyright 2016 Kurt Kim Schaefer University of Washington Abstract The Promise and the Price of Contact: Puyallup Indian Acculturation, Federal Indian Policy and the City of Tacoma, 1832-1909 Kurt Kim Schaefer Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. John Findlay Department of History History shows that Native American contact with Euro-Americans led to many Indians’ loss of land, resources, and independence. Between 1832 and 1909, numerous Puyallup Indians of the south Puget Sound suffered this fate as they dealt with newly imported Euro-American diseases and colonialism. As tragic as this era in history was to the Puyallup, it was also a time when many tribal members continued a long tradition of embracing outside influences into their lives and shaping them to fit their cultural needs. This study will show that prior to 1832, the Puyallup had a long, complex, and generally prosperous relationship with other communities in the Puget Sound region and cultural transformation was a normal part of their life. After 1832, change came more quickly and, unfortunately, was more destructive. Nevertheless, many Puyallup continued accepting change and some successfully shaped their new situation to fit their needs, just as their ancestors had done.