Glocalization in China: an Analysis of Coca-Cola's Brand Co-Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHIL 269: Philosophy of Sex and Love: Course Outline

PHIL 269: Philosophy of Sex and Love: Course Outline 1. Title of Course: Philosophy of Sex and Love 2. Catalogue Description: The course investigates philosophical questions regarding the nature of sex and love, including questions such as: what is sex? What is sexuality? What is love? What kinds of love are possible? What is the proper morality of sexual behavior? Does gender, race, or class influence how we approach these questions? The course will consider these questions from an historical perspective, including philosophical, theological and psychological approaches, and then follow the history of ideas from ancient times into contemporary debates. A focus on the diversity theories and perspectives will be emphasized. Topics to be covered may include marriage, reproduction, casual sex, prostitution, pornography, and homosexuality. 3. Prerequisites: PHIL 110 4. Course Objectives: The primary course objectives are: To enable students to use philosophical methods to understand sex and love To enable students to follow the history of ideas regarding sex and love To enable students to understand contemporary debates surrounding sex and love in their diversity To enable students to see the connections between the history of ideas and their contemporary meanings To enable students to use (abstract, philosophical) theories to analyze contemporary debates 5. Student Learning Outcomes The student will be able to: Define the direct and indirect influence of historical thinkers on contemporary issues Define and critically discuss major philosophical issues regarding sex and love and their connections to metaphysics, ethics and epistemology Analyze, explain, and criticize key passages from historical texts regarding the philosophy of sex and love. -

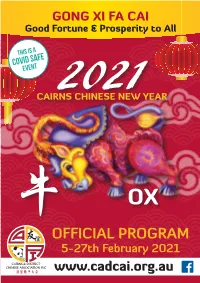

Cny 2021 Program

GONG XI FA CAI Good Fortune & Prosperity to All THIS IS A COVID SAFE EVENT 2021 CAIRNS CHINESE NEW YEAR OX OFFICIAL PROGRAM 5-27th February 2021 www.cadcai.org.au Lions and Dragons the sights and sounds of Chinese New Year SATURDAY 6 FEBRUARY – SATURDAY 6 MARCH 2020 CAIRNS MUSEUM CNR LAKE AND SHEILDS ST, CAIRNS Lions and Dragons Welcome the sights and sounds of Chinese New Year A Message from the President of Cairns & District Chinese Association Inc On behalf of our Chinese Community in FNQ ‘Gong Xi Fa Cai’, we welcome you to join us in the 2021 Cairns Chinese New Year Festival’s “Year of the OX”. 145 years ago, Chinese immigrants began to settle in Cairns, due to the decline of the Palmer River gold rush. Through two world wars, and a great depression, the local Chinese community has linked arms with all others to face every challenge head on. Through man-made hardship, to the astonishing natural disasters we face year to year, the multicultural community of Cairns has overcome all. We now face yet another worldwide challenge, this time, the COVID 19 pandemic. Again, the Cairns Chinese community has linked arms with the wider community and banded together to get through these difficult times which affect us all. As each year passes, the Cairns Chinese Community has not only continued to grow in numbers, we also continue our legacy of sharing our rich history, full of culture, age old traditions and delicious mouth-watering food with the locals and broader community. The Lunar New Year Festival has a history of over 3,000 years with celebrations dated back to the ancient worship of heaven and earth. -

Philosophy of Love and Sex Carleton University, Winter 2016 Mondays and Wednesdays, 6:05-7:25Pm, Azrieli Theatre 301

PHIL 1700 – Philosophy of Love and Sex Carleton University, winter 2016 Mondays and Wednesdays, 6:05-7:25pm, Azrieli Theatre 301 Professor: Annie Larivée Office hours: 11:40-12:40pm, Mondays and Wednesdays (or by appointment) Office: 3A49 Paterson Hall Email: [email protected] Tel.: (613) 520-2600 ext. 3799 Philosophy of Love and Sex I – COURSE DESCRIPTION Love is often described as a form of madness, a formidable irrational force that overpowers our will and intelligence, a condition that we fall into and that can bring either bliss or destruction. In this course, we will challenge this widely held view by adopting a radically different starting point. Through an exploration of the Western philosophical tradition, we will embrace the bold and optimistic conviction that, far from being beyond intelligibility, love (and sex) can be understood and that something like an ‘art of love’ does exist and can be cultivated. Our examination will lead us to question many aspects of our experience of love by considering its constructed nature, its possible objects, and its effects –a process that will help us to better appreciate the value of love in a rich, intelligent and happy human life. We will pursue our inquiry in a diversity of contexts such as love between friends, romantic love, the family, civic friendship, as well as self-love. Exploring ancient and contemporary texts that often defend radically opposite views on love will also help us to develop precious skills such as intellectual flexibility, critical attention, and analytic rigor. Each class will be devoted to exploring one particular question based on assigned readings. -

Thomas Ricklin, « Filosofia Non È Altro Che Amistanza a Sapienza » Nadja

Thomas Ricklin, « Filosofia non è altro che amistanza a sapienza » Abstract: This is the opening speech of the SIEPM world Congress held in Freising in August 2012. It illustrates the general theme of the Congress – The Pleasure of Knowledge – by referring mainly to the Roman (Cicero, Seneca) and the medieval Latin and vernacular tradition (William of Conches, Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Brunetto Latini), with a special emphasis on Dante’s Convivio. Nadja Germann, Logic as the Path to Happiness: Al-Fa-ra-bı- and the Divisions of the Sciences Abstract: Divisions of the sciences have been popular objects of study ever since antiquity. One reason for this esteem might be their potential to reveal in a succinct manner how scholars, schools or entire societies thought about the body of knowledge available at their time and its specific structure. However, what do classifications tell us about thepleasures of knowledge? Occasionally, quite a lot, par- ticularly in a setting where the acquisition of knowledge is considered to be the only path leading to the pleasures of ultimate happiness. This is the case for al-Fa-ra-b-ı (d. 950), who is at the center of this paper. He is particularly interesting for a study such as this because he actually does believe that humanity’s final goal consists in the attainment of happiness through the acquisition of knowledge; and he wrote several treatises, not only on the classification of the sciences as such, but also on the underlying epistemological reasons for this division. Thus he offers excellent insight into a 10th-century theory of what knowledge essentially is and how it may be acquired, a theory which underlies any further discussion on the topic throughout the classical period of Islamic thought. -

Celebrated in Many Asian Cultures As the Beginning of a New Year. Lunar New Year, Or Spring

The new Lunar calendar has begun – celebrated in many Asian cultures as the beginning of a new year. Lunar New Year, or Spring Festival, is one of the most important holidays in Asian cultures. Tied to the lunar calendar, the holiday was traditionally a time to honor household and heavenly deities and ancestors. It’s a time to bring family together for feasting. The Lunar New Year is marked by the first new moon of the lunisolar calendars traditional to many east Asian countries, which are regulated by the cycles of the moon and sun. In China (Chinese New Year), the 15-day celebration kicks off on New Year's Eve with a family feast called a reunion dinner full of traditional Lunar New Year foods, and typically ends with the Festival of Lanterns, when the full moon arrives. It’s important to note that the Lunar New Year isn't only observed in China and is celebrated across several countries and other territories in Asia, including South Korea, Vietnam, and Singapore among others. When is the Lunar New Year? This year, Lunar New Year begins February 12, 2021. Zodiac Animal Signs The lunar calendar has 12 zodiac animal signs which rotate every year, as opposed to every month like in the Gregorian calendar. Each new year is marked by the characteristics of one of the zodiac animals: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. February 2021 starts the year of the Ox. The Ox has traits of strength, reliability, fairness and conscientiousness, as well as inspiring confidence in others. -

Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Quarter 2 - Module 8: the Meaning of His/Her Own Life

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Regional Office IX, Zamboanga Peninsula 12 Zest for Progress Zeal of Partnership Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Quarter 2 - Module 8: The Meaning of His/Her Own Life Name of Learner: ___________________________ Grade & Section: ___________________________ Name of School: ___________________________ WHAT I NEED TO KNOW? An unexamined life is a life not worth living (Plato). Man alone of all creatures is a moral being. He is endowed with the great gift of freedom of choice in his actions, yet because of this, he is responsible for his own freely chosen acts, his conduct. He distinguishes between right and wrong, good and bad in human behavior. He can control his own passions. He is the master of himself, the sculptor of his own life and destiny. (Montemayor) In the new normal that we are facing right now, we can never stop our determination to learn from life. ―Kung gusto nating matuto maraming paraan, kung ayaw naman, sa anong dahilan?‖ I shall present to you different philosophers who advocated their age in solving ethical problems and issues, besides, even imparted their age on how wonderful and meaningful life can be. Truly, philosophy may not teach us how to earn a living yet, it can show to us that life is worth existing. It is evident that even now their legacy continues to create impact as far as philosophy and ethics is concerned. This topic: Reflect on the meaning of his/her own life, will help you understand the value and meaning of life since it contains activities that may help you reflect the true meaning and value of one’s living in a critical and philosophical way. -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

Theories of Political Action

1 THEORIES OF POLITICAL ACTION POLS 520, Spring 2013 Professor Bradley Macdonald Office: C366 Clark Office Hours: TW 2-3:30 or by appointment Telephone #: 491-6943 E-mail: [email protected] Preliminary Remarks: The character of political theory is intimately related to the diverse political practices in which the theorist wrote. Particularly in the contemporary period, theorists have increasingly recognized this political nature to their enterprise by clarifying the linkages of their theory to politics and by rethinking the way in which their ideas may promote social and political change. This critical reassessment has become particularly important in the wake of the dissolution of both classical liberalism and classical Marxism as political ideologies guaranteeing universal human emancipation, not to mention providing conceptual tools to understand the unique political dilemmas facing political actors in the 21st century. If there have been differing ideologies and theories that have confronted new conditions, there are also different strategies and tactics that have been increasingly revamped and rearticulated to engage our contemporaneity. If anything, the present century increasingly gives rise to issues associated with the nature of the “political.” How do we define political action and political knowledge? In what way is politics related to cultural practices (be they art, popular culture, or informational networks)? In what way is political action imbricated within economic practices? How has politics changed given the processes associated with globalization? This course will attempt to explore some of the more important developments within recent theory associated with defining differing positions on the nature of politics and the political. -

Hegel Between Criticism and Romanticism: Love & Self

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2017 Hegel Between Criticism and Romanticism: Love & Self-consciousness in the Phenomenology Scott onJ athan Cowan University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Cowan, Scott onJ athan, "Hegel Between Criticism and Romanticism: Love & Self-consciousness in the Phenomenology" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1457. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HEGEL BETWEEN CRITICISM AND ROMANTICISM: LOVE & SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE PHENOMENOLOGY by Scott Jonathan Cowan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Philosophy at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2017 ABSTRACT HEGEL BETWEEN CRITICISM AND ROMANTICISM: LOVE & SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE PHENOMENOLOGY by Scott Jonathan Cowan The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Dr. William F. Bristow Hegel’s formulation of self-consciousness has decisively influenced modern philosophy’s notion of selfhood. His famous discussion of it appears in Chapter IV of the Phenomenology of Spirit, and emphasizes that self-consciousness is a dynamic process involving social activity. However, philosophers have struggled to understand some of the central claims Hegel makes: that self- consciousness is (a) “desire itself” which (b) is “only satisfied in another self-consciousness”; and that (c) self-consciousness is “the concept of Spirit.” In this paper, I argue that Hegel’s early writings on love help make sense of the motivation behind these claims, and thereby aids in understanding their meaning. -

Feb 2018.Cdr

VOL. XXX No. 2 February 2018 Rs. 20.00 The Chinese Embassy in India held a symposium with The Chinese Embassy in India, ICCR and China some eminent people of India. Federation of Literary and Art Circles co-hosted Guangzhou Ballet Performance. Ambassador Luo Zhaohui met with a delegation from the Ambassador Luo Zhaohui met with students from Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC. Experimental School of Capital Normal University. Minister and DCM Mr. Li Bijian participated in an activity Diplomats of Chinese Embassy attended the in Jindal Global University. International Food Festival in JNU. Celebrating Spring Festival 1. Entering the Year of the Dog 4 2. Old, New Customs to Celebrate China’s Spring Festival 7 3. China Focus: Traditional Spring Festival Holiday Picks up New Ways 10 of Spending 4. China Focus: Spring Festival Travel Mirrors China’s Changes Over 40 Years 13 5. China Holds Spring Festival Gala Tour for Overseas Chinese 15 6. 6.5 Mln. Chinese to Travel Overseas During Spring Festival Holiday 16 7. Time for Celebrating Chinese New Year 17 8. Indispensable Dishes that Served During China’s Spring Festival 19 9. Spring Festival: Time to Show Charm of Diversification with 56 Ethnic Groups 21 External Affairs 1. Xi Jinping Meets with UK Prime Minister Theresa May 23 2. Xi Jinping Meets with King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands 25 3. Working Together to Build a Better World 26 4. Li Keqiang and Prime Minister Theresa May of the UK Hold Annual 31 China-UK Prime Ministers’ Meeting 5. Li Keqiang Meets with Foreign Minister Taro Kono of Japan 33 6. -

Retail Opportunities and Chinese New Year

1 How to maximise retail opportunities from Chinese New Year 24 January 2019 Housekeeping 2 • Today’s webinar is scheduled to last 1 hour including Q&A • All dial-in participants will be muted • Questions can be submitted at any time via the Go to Webinar ‘Questions’ screen • The webinar recording will be circulated after the event Agenda 3 1 May Yang, Marketing Manager, UnionPay International • Features of Outbound Tourism in 2018 • Performance of Key Markets in Europe • Mobile Payment for Outbound Travelers • Travel Destination Campaign - Europe 2 Marho Bateren, Market Intelligence Analyst, Planet • Introducing Chinese New Year • Chinese New Year Shopper Behaviour • Tourist Arrivals Forecast 3 Q&A Session About UnionPay International 4 UnionPay International (UPI) is a subsidiary of China UnionPay focused on the growth and support of UnionPay’s global business. • In partnership with more than 2000 institutions worldwide, • Established card acceptance in 174 countries and regions • Issuance in 50 countries and regions. • UnionPay International provides high quality, cost effective and secure cross-border payment services to the world’s largest cardholder base • Ensures convenient local services to a growing number of global UnionPay cardholders and merchants. 5 May Yang Marketing Manager, UnionPay International 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Marho Bateren Market Intelligence Analyst, Planet Shopping and Arrivals Growth - Summary – 2018 31 Top 5 Destination Markets Tax Free Sales Vouchers / Avg. Transaction Arrivals -1% Turnover Transactions Values (ATV) Total Sales France 3% -2% 5% 4% United Kingdom -10% -11% 1% 3% -6% Italy 7% 3% 4% 6% Total Spain -8% -5% -3% 2% Vouchers Germany -4% -9% 6% -1% +6% Top 5 Source Markets Total ATV Tax Free Sales Vouchers / Avg. -

Why Rawlsian Liberalism Has Failed and How Proudhonian Anarchism Is the Solution

A Thesis entitled Why Rawlsian Liberalism has Failed and How Proudhonian Anarchism is the Solution by Robert Pook Submitted to the graduate faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy __________________________________ Dr. Benjamin Pryor, Committee Chair __________________________________ Dr. Ammon Allred, Committee Member __________________________________ Dr. Charles V. Blatz, Committee Member __________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2011 An abstract of Why Rawlsian Liberalism has Failed and How Proudhonian Anarchism is the Solution by Robert Pook Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy University of Toledo August 2011 Liberalism has failed. The paradox in modern society between capitalism and democracy has violated the very principles of liberty, equality, and social justice that liberalism bases its ideology behind. Liberalism, in directly choosing capitalism and private property has undermined its own values and ensured that the theoretical justice, in which its foundation is built upon, will never be. This piece of work will take the monumental, landmark, liberal work, A Theory of Justice, by John Rawls, as its foundation to examine the contradictory and self-defeating ideological commitment to both capitalism and democracy in liberalism. I will argue that this commitment to both ideals creates an impossibility of justice, which is at the heart of, and is the driving force behind liberal theory. In liberalism‟s place, I will argue that Pierre-Joseph Proudhon‟s anarchism, as outlined in, Property is Theft, offers an actual ideological model to achieving the principles which liberalism has set out to achieve, through an adequate and functioning model of justice.