Addressing Worklessness and Job Insecurity Among People Aged 50 and Over in Greater Manchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewson Civils

Page 1 JEWSON CIVILS Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Page 2 Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Jewson Civils, Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX INVESTMENT SUMMARY Opportunity to acquire a single let trade counter unit with secure open storage and loading yard. The accommodation totals 43,173 sq ft (4,011 sq m) and benefits from 40 customer parking spaces; Site area of 3.12 acres (1.27 ha) with a low site coverage of 33%; Let to Jewson Ltd (guaranteed by Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Limited) for a term of 15 years from 3 July 2007 (expiring 2 July 2022), providing 2.75 years term certain; A low current passing rent of £213,324 per annum, reflecting only £4.94 per sq ft. Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Limited has a D&B rating of 5A2, representing a minimum risk of business failure; Long Leasehold (808 years unexpired); Offers are sought in excess of £2,855,000 (Two Million, Eight Hundred and Fifty Five Thousand Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level reflects an attractive net initial yield of 7.00% and a capital value of £66 per sq ft (assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.43%). Page 3 Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Jewson Civils, Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX LOCATION Oldham is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, one of the ten boroughs that comprise Greater Manchester conurbation and a major administrative and commercial centre. The town lies approximately 8 miles north east of Manchester City Centre via the A62 (Oldham Road), 4 miles north of Ashton-under-Lyne via A627 (Ashton Road) and 6 miles south of Rochdale via the A671 (Oldham Road). -

Oldham District Budget Report

Report to Oldham District Executive Oldham District Budget Report Portfolio Holder: Cllr B Brownridge, Cabinet Member for Cooperatives & Neighbourhoods Officer Contact: Helen Lockwood, Executive Director, Cooperatives & Neighbourhoods Report Author: Simon Shuttleworth; District Coordinator, Oldham Ext. 4720 27th January 2016 Reason for report To advise the Oldham District Executive of the current budget position and seek approval for proposed items of spend. Recommendations 1. To note the current budget position 2. To make the following budget allocations (revenue, unless stated otherwise): a) Winterbottom Street Bollards £2,700 Capital b) Millennium Green/Sholver Centre £3,000 Capital c) Works to Stoneleigh Park £2,500 Capital d) Crèche for Mindfulness Course £720 e) Football provision at Broadfield School pitch £2,658 f) Waste and litter project £7,126 g) Highways Improvements £20,000 Capital h) Alleygating – Glodwick £2,000 Capital i) Clarksfield Alleyway Initiative £4,300 j) Arundel Street Park £2,000 Capital k) Stoneleigh Park Cabin pool table - £291 Revenue Oldham District Executive 27th January 2016 Oldham District Budget Report 1 Background 1.1 The Oldham District Executive has been assigned the below budget for 2015/2016: Revenue 2015/2016 Capital 2015/2016 Alexandra £10,000 £10,000 Coldhurst £10,000 £10,000 Medlock Vale £10,000 £10,000 St James’ £10,000 £10,000 St Mary’s £10,000 £10,000 Waterhead £10,000 £10,000 Werneth £10,000 £10,000 1.2 Each Councillor also has an individual budget of £5000 for 2015/2016 Allocations to date are shown in the attached Appendix 1 2 Current Position 2.1 Revenue and Capital Budgets Allocations made so far are shown below. -

WARD: Gorse Hill 1308 (08/18) TRAFFORD METROPOLITAN

TRAFFORD METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL Report to: Executive Member for Environment, Air Quality and Climate Change Date: September 2018 Report for: Approval Report of: Principal Engineer, Traffic and Transportation, One Trafford. ELTON STREET, STRETFORD Proposal to introduce a new Disabled Residents’ Permit Parking Space Consideration of objections and proposal to introduce a 2nd disabled residents’ permit bay Summary To consider the objection received and to seek approval to introduce a new disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford To seek approval to advertise the intention to introduce a second disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford Recommendations Agreement is sought to the following: 1. That the introduction of a disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford be approved. 2. That, following careful consideration of the objection received, authorisation be given to make and introduce the Traffic Regulation Order, as advertised. 3. That the objector be notified of the Council’s decision. 4. That the introduction of a second disabled residents’ permit parking space on Elton Street, Stretford be approved. 5. That authorisation be given to advertise the intention of making the Traffic Regulation Order referred to in schedule 3 to this report and, if no objections are maintained, that the Order be made and the proposal implemented. 6. That a consultation be carried out with nearby residents. Contact person for further information: Name: Dorothy Stagg Extension: 0161 6726534 Background Papers: None WARD: Gorse Hill 1308 (08/18) 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 Following the receipt of a request from a disabled resident of 18 Elton Street, Stretford, who is a blue badge holder, a report was circulated in January 2018, considering a proposal to introduce a disabled persons’ permit bay. -

North Locality: Life Expectancy

TRAFFORD NORTH LOCALITY HEALTH PROFILE JANUARY 2021 NORTH LOCALITY: WARDS • Clifford: Small and densely populated ward at north-east tip of the borough. Dense residential area of Victorian terraced housing and a diverse range of housing stock. Clifford has a diverse population with active community groups The area is undergoing significant transformation with the Old Trafford Master Plan. • Gorse Hill: Northern most ward with the third largest area size. Trafford town hall, coronation street studio and Manchester United stadium are located in this ward. Media city development on the Salford side has led to significant development in parts of the ward. Trafford Park and Humphrey Park railway stations serve the ward for commuting to both Manchester and Liverpool. • Longford: Longford is a densely populated urban area in north east of the Borough. It is home to the world famous Lancashire County Cricket Club. Longford Park, one of the Borough's larger parks, has been the finishing point for the annual Stretford Pageant. Longford Athletics stadium can also be found adjacent to the park. • Stretford: Densely populated ward with the M60 and Bridgewater canal running through the ward. The ward itself does not rank particularly highly in terms of deprivation but has pockets of very high deprivation. Source: Trafford Data Lab, 2020 NORTH LOCALITY: DEMOGRAPHICS • The North locality has an estimated population of 48,419 across the four wards (Clifford, Gorse Hill, Stretford & Longford) (ONS, 2019). • Data at the ward level suggests that all 4 wards in the north locality are amongst the wards with lowest percentages of 65+ years population (ONS, 2019). -

Central Ward

Swindon Borough Council Open Space Audit and Assessment Update Part B: Ward Profiles March 2014 Open Space Audit and Assessment Update: Part B NOTES 1. For the purposes of assessing open space provision, the standard of 3.2 ha per 1000 population will be used as set out in the Swindon Borough Local Plan 2011 (saved policy R4 ‘Protection of Recreation Open Space’ (March 2011)). The draft Swindon Borough Local Plan 2026 seeks to continue this standard and will inform emerging work on Green Infrastructure. 2. This update has predominantly been prepared to reflect the ward boundary changes in 2012; data collated in May 2010 has therefore been used for this update to the open space ward profiles. 3. Outdoor sports facilities and playing pitches have not been updated since the review of the Playing Pitch Strategy in 2007. An update of the Playing Pitch Strategy will be undertaken in 2014. 4. All school playing fields and private pitches that do not have community access have been excluded from these profiles. 5. Playing pitches with community access are included within the overall totals for outdoor sports facilities. 6. Where country parks and golf courses exist, they have been listed in the Ward Profile schedules; however they do not contribute towards the open space standard as they are considered to be a Borough wide resource. 7. All population figures have been taken from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Census 2011. A SASPEC methodology was then used to align the data with the revised Swindon Borough ward boundaries. 8. The quality for each open space is illustrated through the use of the following colours: Quality Standard Scoring Range Colour Under Standard Under 49.99% At Standard 50% - 69.99% Above standard Above 70% 9. -

Past Forward 31

ISSUE No. 31 SUMMER 2002 The Newsletter of Wigan Heritage Service FREE From the Editor EUROPE IN FOCUS WELCOME to the summer edition of Past Forward. As always, you will find a splendid mix of articles Angers 2002 by contributors old and new. These are exciting times for the Heritage Service, which has ANGERS is twinned with will be loaned to Angers for the enjoyed an international profile of Wigan, and indeed with a exhibition. Local firms Millikens late - worldwide publicity followed number of other towns, and William Santus, as well as Alan Davies’s feature in the last including Osnabruck, Pisa, Wigan Rugby League Club, have issue of the recently discovered Haarleem and Seville. During also made contributions to treasure Woman’s Worth (see p3), September, the French town will Wigan’s part of the exhibition. while the History Shop was featured in the final episode of be mounting a major exhibition, Wigan Pier Theatre Company Simon Shama’s History of Britain, ‘Europe in Focus’, which will will also be taking part, as will shown in June. And the Service feature displays and John Harrison, a young flautist has played a key role in Wigan’s contributions from all its from Winstanley College, Wigan. contribution to a major exhibition in twinned towns. I will ensure that a plentiful Angers, its twin town, in Wigan Heritage Service has supply of Past Forward will be September (see right). played a leading role in Wigan’s available - a good opportunity to Nearer to home, I am delighted with the progress which is being contribution, and a selection of expand the readership on the made by the Friends of Wigan museum artefacts and archives continent! Heritage Service, with lots of exciting projects in the pipeline. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors for the Wards listed below Number of Number of District District Wards Wards Councillors to Councillors to be elected be elected Altrincham One Hale Barns One Ashton Upon Mersey One Hale Central One Bowdon Two Longford Two Broadheath One Priory Two Brooklands One Sale Moor One Bucklow-St Martins One St Mary's One Clifford One Stretford One Davyhulme East One Timperley One Davyhulme West One Urmston One Flixton Two Village One Gorse Hill One 1. Nomination papers for this election can be downloaded from the Electoral Commission website or may be obtained from the Returning Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Completed nomination papers must be delivered by hand to the Returning Officer, Committee Room 1 Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, on any weekday (Monday to Friday inclusive (excluding bank and public holidays)) after the date of this notice on between 10am and 4pm but no later than 4pm on Thursday 8 April 2021. 3. If any election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday 6 May 2021. 4. Applications to register to vote at this election must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by 12 midnight on Monday 19 April 2021.Applications may be made online: www.gov.uk/register to vote or sent directly to the Electoral Registration Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH. -

WARD: Gorse Hill 79988/FULL/2013 DEPARTURE: No FORMATION OF

WARD: Gorse Hill 79988/FULL/2013 DEPARTURE : No FORMATION OF SUBTERR ANEAN WASTEWATER DET ENTION FACILITY WITH THE ERECTION OF A MOTOR CONTROL CENTRE, METER KIOSK, 25M HIGH PRESSURE RELIEF COLUMN AND PALADIN FENCING AROUND SITE PERIMETER. FORMATION OF NEW VEHICULAR ACCESS FROM FRASER PLACE, ADDITIONAL AREAS OF HARDSTANDING AND ASSOCIATED LANDSCAPING WORKS ALSO. Electric Park, off Fraser Place Trafford Park APPLICANT: United Utilities AGENT: United Utilities RECOMMENDATION: GRANT SITE The application site relates to a vacant plot of land directly to the north of Fraser Place, which is broadly rectangular in shape and measures 0.715 hectares in size. It spans a length of some 115m, separating the complex of buildings relating to ‘Westmill Foods’ to the north, from the Fraser Place highway to the south. A 2m high paladin fence secures the southern boundary in its entirety and as a result presently prevents vehicular access onto the land. The application site represents the central section of what is in fact a wider undeveloped plot that covers 2.4 hectares. Consequently areas of open land directly adjoin the eastern and western boundaries of the application site. The site sits within the heart of Trafford Park, and the character of the surrounding area is typical of an industrial estate. Land on the southern side of Fraser Place is occupied by ‘Kellogg’s’, with its substantial vehicular entrance located directly opposite the application site. Other businesses of note in the vicinity include ‘Hovis’, whose premises sit to the north- east, and the aforementioned ‘Westmill Foods’ immediately to the north. The Bridgewater canal runs broadly north-south approximately 240m away to the east. -

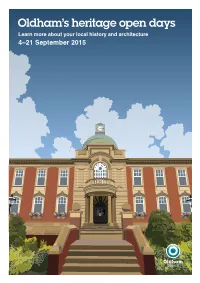

Oldham's Heritage Open Days

Oldham’s heritage open days Learn more about your local history and architecture 4–21 September 2015 12pp Heritage OD leaflet 2015 .indd 1 04/08/2015 14:53 Welcome to Oldham Council’s Heritage Open Days, your opportunity to find out more about the history and heritage of your area. From talks to walks there’s plenty to discover, whether you’re interested in architecture or heritage or just curious about the history around you. 6-21 September Every Monday and Wednesday A Tale of the Dardanelles Family History Advice A display telling the story of the 2pm-4pm: Needing help with family Oldham Territorials at Gallipoli. history? Expert advice available. Oldham Local Studies and Archives, Oldham Local Studies and Archives, 84 Union Street, Oldham OL1 1DN. 84 Union Street, Oldham OL1 1DN. Mon and Thurs 10am-7pm; Tues Disabled access; toilets 10am-2pm; Wed and Fri 10am-5pm; Sat 10am-4pm. 4-6 September Disabled access; toilets Flower festival 12noon-5pm: Holy Trinity Church, Oldham Town Centre Shaw. Commemorating the 500th Past and Present anniversary of the site being a place Photographs comparing Oldham of worship. Church Road, Shaw, Town Centre of today with that of the Oldham, OL2 7SL. Disabled access; past. Oldham Town Centre Office, toilets; parking; refreshments 12 Albion Street, Oldham, OL1 3BG. Mon-Fri 10am-5pm. Disabled access Saturday 5 September Growing Up in Old St Mary’s Holy Trinity Church, Bardsley Display of photographs, books 9am-12noon: Find out more about and memories of the making of the the church and its community; documentary ‘Just Like Coronation includes tours of clock tower. -

Official Directory. (Slater's

1982 OFFICIAL DIRECTORY. (SLATER'S Bury' Co-operative Manufacturing Cb. Ltd. Haugh Cotton Spinning & Manufacturing Co Park Road Spinning Co. Ltd. Dukinfteld Wellington mills, Elton, Bury Ltd. Newhey, near Rochdale Parkside Spinning Uo. Ltd. Royton Bury Cotton Spinning and Manufacturing Co. Ha.worth Richard & Oo. Ltd. Egerton, Tatton Patrrson F. G. & Co. 13 St. Ann l't Ltd. Barnbrook mills, Bury Ordsal 1.< Tbrostle Nest mtlls, Ordsal, Salforcl Pearl Mill Co. Ltd. Glodwick, Oldham Busk Mills Co. Ltd. Busk mills; Blli!k, Oldham Heginbottom B. & Sons, Ltd. Junction milLs, Peel Ro:5er & Jame& Henry, Frceto>vn and Butterworth Alfred, Glebe mills, Holllnwood Ashton-unrler-Lyne Hope mills, Bury ButlA'rworth Edwin & Co. Pollard st Hey Spinning Oo. Ltd. Sun Hill mill, Hey, Peel Spinning and Manufacturing Co. Ltd. Byrom J. R. (Joseph Byrom & Sons), Royal, Lee~, near Oldham Chamber hall, Bury A.l bion and Victoria. mills, Droylsden Hirst R.& Sons. Firth Street mills, Huddera field Peers Robert, Brookllmouth mill, Elton, Bury Bythell J. K. Sedgley park, Prestwich Hobson T. A. S. 26 Corpoi"!ltion st Phillips Frederick, 96 Deansgate Campbell H. E ..Manche3ler Hollinwood Spinning Co. Ltd. Hollinwood, Pick up J ames & Brother, Ltd. Spring and Isle Canal Mills Co. (Ciayton-le-Moors), Ltd. Clay- near Oldham of Man mills, Newcb.urch ton-le-Moors Holly Mill Co. Ltd. Royton Pine Mill Co. Ltd. North Moor, Oldham Carver Brothers & Co. Ltd. 30 St. Ann st Honeywell Cotton Spinning Oo. Ltd. Ashton Platt Bros. & Co. LW. Oldllam Castle Spinning Co. Ltd. Quay st. Stalybridge rd. Oldham Platt Ed. Ld. Clough mill~, Hayfield) near Central Mill Co. -

402 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

402 bus time schedule & line map 402 Oldham - Royal Oldham Hospital - Royton Circular View In Website Mode The 402 bus line (Oldham - Royal Oldham Hospital - Royton Circular) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Derker: 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM (2) Oldham: 7:32 AM - 5:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 402 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 402 bus arriving. Direction: Derker 402 bus Time Schedule 115 stops Derker Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Thackeray Road, Derker Whetstone Hill Lane, Manchester Tuesday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Wordsworth Road, Derker Wednesday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Vulcan Street, Derker Thursday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Friday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Abbotsford Road, Derker Abbotsford Road, Manchester Saturday 8:30 AM - 3:30 PM Stoneleigh Street, Derker Sydenham Street, Derker Sydenham Street, Manchester 402 bus Info Direction: Derker London Road, Derker Stops: 115 Roseberry Avenue, Manchester Trip Duration: 114 min Line Summary: Thackeray Road, Derker, Yates Street, Derker Wordsworth Road, Derker, Vulcan Street, Derker, Abbotsford Road, Derker, Stoneleigh Street, Derker, Bartlemore Street, Derker Sydenham Street, Derker, London Road, Derker, Yates Alexandra Crescent, Manchester Street, Derker, Bartlemore Street, Derker, Acton Street, Derker, Derker Metrolink Stop, Derker, Yates Acton Street, Derker Street, Derker, Derker Metrolink Stop, Derker, Acton Street, Manchester Kirsktone Close, Oldham Edge, Edge Lane Road, Oldham Edge, Charter Street, -

SHOLVER Final Report

Oldham Rochdale HMR Pathfinder Heritage Assessment SHOLVER Final Report March 2008 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1 2 METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................................5 3 PLANNING & REGENERATION CONTEXT ..............................................................13 4 THE SHOLVER AREA ................................................................................................20 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................60 APPENDICES A Project Brief B Consultation Report (See Separate Cover) MAPS (SEPARATE) 01 Historic Framework 02 Historic Development 03 Heritage Value Research and text by Richard Morriss of Richard K Morriss & Associates, with Mike Dawson of CgMS and Chris Garrand of the Christopher Garrand Consultancy. Public consultation and reporting led by Jon Phipps of Lathams (project director). Mapping, graphics and photography by Mark Lucy, Sarah Jenkins and Tom Mason of Lathams, with Chris Garrand and Bibiana Omar Zajtai. © Lathams, 2008 Document produced in partnership with: Oldham Rochdale HMR Pathfinder Heritage Assessment SHOLVER 1 INTRODUCTION Insert Photo in lieu of 20% Tint swatch (de- lete this frame) 1 Introduction 1.01 BACKGROUND Lathams: Urban Design in association with the Christopher Garrand Consultancy, Richard K. Morriss & Associates, and CgMS have been commissioned