Consumer Food Safety Behavior: a Case Study in Hamburger Cooking and Ordering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

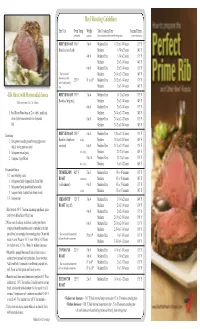

Star Ranch Angus Beef Brochure

EXPERIENCE THE ANGUS DIFFERENCE. Your Guide to Cooking Fresh Beef. Copyright ©2006 Tyson Foods, Inc. OVEN ROASTS OVEN ROASTS 1 Heat oven to temperature on chart. Place roast, fat side up, on rack in shallow roasting pan. Insert ovenproof meat thermometer so tip is centered in thickest part of roast. Do not add water or cover. 2 Roast according to chart. Remove when meat thermometer registers 135° to HOW TO COOK TODAY'S BEEF 140°F for medium rare,150° to 155°F for medium. Let the roast POT ROAST/ BRAISING stand 15 minutes. (Temperature will continue to rise 5° to 10°F to STEWING reach desired doneness and roast will be easier to carve.) GRILLING OVEN BEEF CUT TEMP. WEIGHT TOTAL COOKING TIME ROASTING (preheated) STIR- FRYING Tri-Tip Roast 425°F 1-1/2 to 2 lbs. Med. rare: 30 to 40 min. BROILING Med.: 40 to 45 minutes SKILLET Eye Round 325°F 2 to 3 lbs. Med. rare: 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 hrs. Roast BEEF CUT Recommended cooking to medium rare (145º F) doneness only. CHUCK Chuck, Top Blade Steak Round Tip 325°F 3 to 4 lbs. Med. rare: 1-3/4 to 2 hrs. Chuck Eye Steak, boneless Roast Med.: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hrs. Chuck Shoulder Steak, boneless 4 to 6 lbs. Med. rare: 2 to 2-1/2 hrs. Chuck Arm Steak Med.: 2-1/2 to 3 hrs. Chuck 7-Bone Steak 6 to 8 lbs. Med. rare: 2-1/2 to 3 hrs. Chuck Pot Roast, such as Arm, Blade, Shoulder Med.: 3 to 3-1/2 hrs. -

Download Private Reserve Preparation Guide

Preparation Guide Steak & Chop Cooking Chart The cooking times below are in minutes and based on fully thawed steaks or chops . Gas Grill – Preheat grill to high, reduce to medium heat prior to cooking. Charcoal Grill – Sear over red hot coals, finish over indirect heat. Thickness 1” 1 1/4” 1 1/2” 1 3/4” 2 2 1/4” 2 1/2” Rare First Side 6 6 7 9 11 13 14 120˚- 130˚F After Turning 3-4 4-5 5-6 6-7 7-8 8-9 10-12 Medium Rare First Side 6 7 8 11 13 14 16 130˚-140˚F After Turning 4-5 5-6 6-7 8-9 9-10 10-12 11-14 Medium First Side 7 8 9 12 14 16 17 140˚-150˚F After Turning 5-6 6-7 7-8 9-10 11-12 12-14 14-16 Well Done First Side 9 10 12 14 18 19 20 160˚-170˚F After Turning 7-8 8-9 9-11 12-14 14-16 16-18 21-23 Sear Roasting – Preheat oven to 300˚F. Heat a small amount of oil in a large ovenproof pan over high heat. Sear meat for 2-3 minutes on first side or until well browned. Flip meat; then place in preheated oven. Thickness 1” 1 1/4” 1 1/2” 1 3/4” 2 2 1/4” 2 1/2” Rare First Side 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 120˚- 130˚F After Turning 3-4 5-7 9-11 14-15 16-17 18-21 22-25 Medium Rare First Side 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 130˚-140˚F After Turning 5-6 9-11 13-16 18-19 20-22 22-25 26-30 Medium First Side 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 140˚-150˚F After Turning 8-10 12-15 16-19 23-24 24-26 26-30 32-38 Well Done First Side 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 2-3 160˚-170˚F After Turning 12-15 16-19 20-24 28-32 32-36 36-42 42-50 Omaha Steaks test kitchen equipment may vary from yours in the amount of heat produced. -

Metro Dining Club Is Offering You and Your Family an Opportunity to Enjoy an Entire Year of 2 for 1 Dining Pleasure at 166 Area Restaurants

ETRO INING LUB MBecome a Member Today D and Save Hundreds C of Dollars!!!!! 803 Bielenberg Dr Woodbury 651-478-7511 www.machetecm.com 2900 rice Street • Little canada • 651-486-7719 www.littlevenetian.squarespace.com 501 6th Street North Hudson, Wis 715-386-8488 See Reverse for Participating Locations Welcomes You and Your Guest Welcomes You To Enjoy To Enjoy One Complimentary Entree $15.00 OFF When a Second Entree of Equal or Any Food Order of $30.00 or More Greater Value is Purchased VALID ANYTIME • ONCE PER MONTH VALID ANYTIME • ONCE PER MONTH Must Purchase a Minimum of 2 Beverages Per Card MUST PURCHASE A MINIMUM OF 2 BEVERAGES PER CARD ST. PAUL/WESTERN WISCONSIN PROGRAM www.metrodiningclub.com | facebook.com/metrodiningclub | twitter.com/metrodiningclub 2nd Street Depot Celts Craft House El Neuvo 7 Mares JT’s Food & Cocktails Paradise Car Wash Suishin Restaurant 7-10 Grille Celts Pub El Parian - Eagan Jordan Meats Deli Park Cafe Taco Fresh Acapulco Cheap Andy’s El Pariente Mexican Grill Karta Thai Park Grove Pub Taco Fresh Cantina Adagio’s Pizza Factory Cherokee Tavern El Taquito Klinkers Korner Park Place Taco John’s American Burger Bar Cherry Berry Enrique’s Mexican Kyoto Sushi Pete’s Pizza The Grateful Table American Legion Bayport Cherry Pit Farmington Tap House La Costa Mexican Peterson Popcorn Tinucci’s (2) Angelo’s Pizza Chevys Fiesta Cancun LaPalma Cafe Pino’s Pizza Titans Sports Saloon Ansari’s Chisago House Lino Lakes Little Venetian Pita Pit Tom Reids Hockey Pub Auntie Anne’s Cold Stone Creamery Fiesta Cancun Longbranch -

Determination of Internal Color of Beef Ribeye Steaks Using Digital Image Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Food Structure Volume 5 Number 2 Article 6 1986 Determination of Internal Color of Beef Ribeye Steaks Using Digital Image Analysis K. Unklesbay N. Unklesbay J. Keller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Unklesbay, K.; Unklesbay, N.; and Keller, J. (1986) "Determination of Internal Color of Beef Ribeye Steaks Using Digital Image Analysis," Food Structure: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure/vol5/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Food Structure by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD MICROSTRUCTURE, Vol. 5 (1986), pp. 227-231 0730- 5419/86$1. 00+. OS SEM, Inc. , AMF O'Hare (Chicago), IL 60666-0507 U.S.A. DETERMINATION OF INTERNAL COLOR OF BEEF RIBEYE STEAKS USING DIGITAL IMAGE ANALYSIS K. Unklesbay, N. Unklesbay#, J. Keller El ectri ca 1 and Computer Engineering Department College of Engineering, #Food Science and Nutrition Department College of Agriculture, University of Missouri-Columbia Columbia, MO 65211 Introduction Objective measurements of beef ribeye steaks were The increased use of sophisticated heat made to determine the color distribution through processing equipment in the food industry has out their interior after heat processing. Steaks made the need for further quantification of food from eight animals were grilled to five degrees quality increasingly important. -

Beef Roasting Guidelines

Beef Roasting Guidelines Beef Cut Oven Temp. Weight Total Cooking Time Internal Temp. (preheated) (pounds) (based on meat directly from the refrigerator) (remove from oven) RIBEYE ROAST 350˚ F 3 to 4 Medium Rare: 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 hours 135˚ F Boneless (small end) Medium: 1-3/4 to 2 hours 145˚ F 4 to 6 Medium Rare: 1-3/4 to 2 hours 135˚ F Medium: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 145˚ F 6 to 8 Medium Rare: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 135˚ F * Tent loosly with Medium: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 145˚ F aluminum foil half- 325˚ F 8* to 10* Medium Rare: 2-1/2 to 3-1/4 hours 135˚ F way through roasting time. Medium: 3 to 3-3/4 hours 145˚ F -Rib Roast with Horseradish Sauce RIBEYE ROAST 350˚ F 3 to 4 Medium Rare: 1-1/2 to 2 hours 135˚ F Total recipe time: 2-1/2 to 3 hours Boneless (large end) Medium: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 145˚ F 4 to 6 Medium Rare: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 135˚ F 1 beef Ribeye Roast bone-in (2 to 4 ribs), small end, Medium: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 145˚ F chine (back) bone removed (6 to 8 pounds) 6 to 8 Medium Rare: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 135˚ F Salt Medium: 2-1/2 to 2-3/4 hours 145˚ F Seasoning: RIBEYE ROAST 350˚ F 4 to 6 Medium Rare: 1-3/4 to 2-1/4 hours 135˚ F 2 tablespoons coarsely ground mixed peppercorns Bone-In (chine bone (2 ribs) Medium: 2-1/4 to 2-3/4 hours 145˚ F (black, white, green and pink) removed) 6 to 8 Medium Rare: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 135˚ F 1 tablespoon minced garlic (2 to 4 ribs) Medium: 2-1/2 to 3 hours 145˚ F 2 teaspoons vegetable oil 8 to 10 Medium Rare: 2-1/2 to 3 hours 135˚ F (4 to 5 ribs) Medium: 3 to 3-1/2 hours 145˚ F Horseradish Sauce: TENDERLOIN 425˚ F 2 to 3 Medium Rare: 35 to 45 minutes 135˚ F 1/2 cup whipping cream ROAST (center-cut) Medium: 45 to 50 minutes 145˚ F 3 tablespoons finely chopped fresh fennel bulb 3 tablespoons finely grated fresh horseradish (well-trimmed) 4 to 5 Medium Rare: 45 to 55 minutes 135˚ F 1 teaspoon finely chopped fresh fennel fronds (whole) Medium: 55 to 65 minutes 145˚ F 1/8 teaspoon salt SIRLOIN TIP 325˚ F 3 to 4 Medium Rare: 1-3/4 to 2 hours 140˚ F ROAST (cap off) Medium: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 150˚ F 1.Heat oven to 350˚ F. -

Format of Short Papers for the 58Th International

OPTIMUM OVEN COOKING PROCEDURE TO IMPROVE PALATABILITY AND COLOUR ATTRIBUTES FOR BEEF INSIDE ROUNDS Argenis Rodas-González1, Ivy L. Larsen1, Bethany Uttaro1, Lorna L. Gibson1, Joyce Parslow2, Manuel Juárez1, and Jennifer L. Aalhus1 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lacombe Research Centre, 6000 C & E Trail, Lacombe, Alberta, Canada T4L 1W1 2Beef Information Centre, 2000 Argentina Road, Plaza 4, Suite 101, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5N 1W1 Abstract – To determine optimum oven cooking II. MATERIALS AND METHODS procedures, the effects of searing temperature (232 or 260°C) and time (0, 10, 20 or 30 min), as Sample collection and cooking well as roasting temperature (160 or 135°C) on A total of 48 inside round sub-primals (~4.5 kg) palatability and colour attributes of from graded Y1 AA [3] carcasses were obtained semimembranosus (SM) muscle were examined. The SM muscles seared for 0 or 10 min at 232°C from a commercial slaughter plant and shipped followed by roast at 135°C had lower cooking loss, to the Lacombe Research Centre (Lacombe, AB, higher external browning colour, more uniform Canada). The sub-primals were aged at 2°C in internal colour, and were more tender and vacuum packages for 14 d. Twelve inside rounds flavourful. As a simplified method, roasting at low were then assigned for each searing time (0, 10, temperature without searing is the preferred oven 20, or 30 min). Inside round sub-primals were cooking procedure. removed from their packaging, dissected and SM were obtained four days prior to cooking. Key Words: cookery method, digital imaging, The SM muscles were trimmed to a square tenderness shape and two steaks from the proximal portion of the muscles were removed for determination I. -

Biol 106 the Science of Steak Health, Environmental, and Ethical

Food and Science Laboratory – Biol 106 The science of steak Health, environmental, and ethical concerns aside, many people like to eat a good steak every once in awhile. The sustainability of steak (meat) eating is currently an area of concern. Clearly a good steak is something we probably should not take for granted. Chefs often refer to the need to respect the meat, i.e. don’t cook it poorly so that it is wasted. Beef steak flavor is distinctive and different than poultry, pork, and game. The ruminant digestive system of cows involves bacteria that break down cellulose, but the bacteria also convert unsaturated fatty acids from plant material into saturated fatty acids. Consequently, beef has a lot of saturated fat which is considered to be unhealthy. The saturated fat also contributes to the “cow-ey” “buttery” flavor of beef. Other compounds such as terpenes can come from eating grass and affect flavor (I personally do not prefer “grassy” beef). Ideally, the perfect steak should be flavorful, moist, and tender. The scientific method of cooking a steak attempts to maximize flavor, moisture, and tenderization. Moisture – A steak that is not dried out is more flavorful in part because soluble compounds that are rich in flavors can coat the tongue and are volatilized for aroma. Most cuts of meat have been processed in which the cut is perpendicular to the direction of the muscle fibers. This makes it easier to break the meat down by chewing, but since every muscle fiber is essentially open at the surface of the steak, the cytoplasmic contents which are the liquid in meat can leak out of the cut surface. -

Steak House Steak House

STEAK HOUSE STEAK HOUSE APPETIZERS SHRIMP COCKTAIL . $7.95 ARTICHOKE SPINACH DIP . $5.95 CRAB STUFFED MUSHROOMS . $6.95 FRIED MUSHROOMS . $4.95 FRIED VEGGIE BASKET . $4.95 Mushrooms, Green Beans, Zucchini LOADED POTATO SKINS . $6.95 ONION RINGS . $4.95 SALADS REGULAR HOUSE GARDEN SALAD . $3.95 Tossed blend of iceberg and romaine lettuce and spring mixed greens, topped with tomatoes, homemade croutons, carrots and cucumbers DINNER GARDEN SALAD . $5.95 Same as regular but large enough for a meal Add Grilled or Fried Chicken . $2.50 CAESAR SALAD . $6.95 Romaine lettuce topped with shredded parmesan, homemade croutons and Caesar Dressing Add Grilled or Fried Chicken . $2.50 CASHEW CHICKEN SALAD . $7.95 Dinner house salad with addition of sliced cucumber, shredded cheddar and cashews With your choice of Grilled or Fried Chicken SALAD DRESSING RANCH THOUSAND ISLAND FRENCH VINEGAR & OIL ITALIAN HOMEMADE RASPBERRY VINAIGRETTE BLUE CHEESE SANDWICHES REUBEN SANDWICH . $5.95 Shaved corned beef, sauerkraut, Swiss cheese and thousand island atop toasted rye bread GRILLED CHICKEN SANDWICH . $7.95 Grilled Chicken Breast, lettuce, tomato on a toasted bun CLUB SANDWICH . $8.95 Smoked turkey breast, ham, bacon, lettuce, cheddar and Swiss cheeses (Mustard or Mayo) CHICKEN SANDWICH . $7.95 Fried Chicken Breast, lettuce, tomato on a toasted bun FRENCH DIP SANDWICH . $7.95 Our succulent Prime Rib trimmed and shaved atop a toasted hoagie roll (Served with Au Jus) PRIME RIB PHILLY SANDWICH . $ 8.95 We take our tender Prime Rib that has trimmed and shaved and pair it with sautéed onions and green bell peppers atop a hoagie roll and broiled with provolone cheese (All sandwiches come with choice of French Fries or Potato Chips) SOUPS BOWL OF FRENCH ONION SOUP . -

The Effects of Cooking Temperature and Stage of Doneness on Some Factors in Broiled Beef

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1963 The Effects of Cooking Temperature and Stage of Doneness on Some Factors in Broiled Beef Carmencita Salvosa Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Salvosa, Carmencita, "The Effects of Cooking Temperature and Stage of Doneness on Some Factors in Broiled Beef" (1963). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4839. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4839 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTS OF COOKING TEMPERATURE AND STAGE OF DONENESS ON SOME FACTORSby IN BROILED BEEF Carmencita Salvosa A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Food and Nutrition . UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY· Logan,1963 Utah ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my deepest gratitude to my major professor, Dr. Margaret B. Merkley, for her patience, untiring personal interest and efforts without which I would still be working on this thesis now. To Dean Phyllis Snow and Dr. Ethelwyn B. Wilcox, I am grateful for their generous help and suggestions throughout the study. To Taylor Instrument Company, I would like to express my appreciation for the loan of the multipoint potentiometer and the special thermometer. To Dr. Rex Hurst I would like to express my thanks for help in the statistical analyses. -

Hamburger Enjoy a Juicy Burger Without Firing up the Grill Thanks to the June Meat Preset for Beef Burgers

WORKS WITH FOOD THERMOMETER & PRESETS Hamburger Enjoy a juicy burger without firing up the grill thanks to the June Meat Preset for Beef Burgers. The June Food Thermometer ensures the patties are cooked to your desired doneness--Medium, Medium Well or Well Done. For best results use ground beef with at least 15% fat. If doubling the recipe, be sure to stagger the 4 patties on the June Roasting Rack as shown on the on-screen tips to ensure even cooking. PREP TIME Ingredients Method 10 minutes 2 hamburger buns, split 1 Place the ground beef in a large mixing bowl. Sprinkle COOK TIME the garlic powder, onion powder, salt and black pepper 20 minutes FOR PATTIES over the beef. Knead together until evenly incorporated. SERVINGS 2/3 pound ground beef 2 Divide the meat in half. Form each half into a ball and 2 ½ teaspoon garlic powder shape into 2 evenly shaped patties at least ½-inch thick. SHELF POSITION ½ teaspoon onion powder Middle ½ teaspoon salt 3 Place the patties on the June Pan lined with the June Roasting Rack. ¼ teaspoon black pepper FOR GARNISH 4 Insert June Food Thermometer so that the tip is in the center of one of the patties. 2 slices cheddar cheese (optional) Mayonaise 5 Place the burger on the middle shelf of the June Oven. Plug in the thermometer into the nearest jack. Mustard Ketchup Presets › Meat › Beef Burgers Sliced onion Follow onscreen instructions to select your desired Sliced tomato doneness and start cooking. June will notify you when the Lettuce burgers are ready. -

Grilling Guidelines

Grilling Guidelines CHARCOAL GRILLING GAS GRILLING (uncovered unless noted) (covered) Approximate Approximate Total Cooking Time Total Cooking Time Weight/ Medium Rare (145°F) Medium Rare (145°F) Beef Cut Thickness to Medium (160°F) to Medium (160°F) CHUCK (minutes) (minutes) Shoulder Top Blade Steak (Flat Iron) 8 ounces each 10 to 14 (grill covered) 12 to 16 Shoulder Steak, boneless (marinate) 3/4 inch 14 to 17 9 to 12 For charcoal grilling, 1 inch 16 to 20 15 to 19 when coals are Shoulder Center Steak (Ranch) 3/4 inch 9 to 11 (grill covered) 8 to 11 medium, ash-covered 1 inch 11 to 14 (grill covered) 12 to 16 (approximately 30 Shoulder Petite Tender Roast 8 to 12 ounces each 14 to 18 (grill covered) 14 to 19 minutes), spread in single layer and check RIB (minutes) (minutes) cooking temperature. Rib Steak, small end 3/4 inch 6 to 8 7 to 10 Position cooking grid. 1 inch 9 to 12 10 to 15 To check temperature, Ribeye Steak 3/4 inch 6 to 8 7 to 9 cautiously hold the 1 inch 11 to 14 9 to 14 palm of your hand above the coals at LOIN (minutes) (minutes) cooking height. Porterhouse/T-Bone Steak 3/4 inch 10 to 12 9 to 13 Count the number 1 inch 14 to 16 15 to 19 of seconds you can Top Loin (Strip) Steak, boneless 3/4 inch 10 to 12 7 to 10 hold your hand in 1 inch 15 to 18 11 to 15 that position before Tenderloin Steak 1 inch 13 to 15 11 to 15 the heat forces you to pull it away; 1-1/2 inches 14 to 16 (grill covered) 16 to 20 approximately SIRLOIN (minutes) (minutes) 4 seconds for Top Sirloin Steak, boneless 3/4 inch 13 to 16 8 to 13 medium heat. -

The Battle on The

14 Business 28 Travel 20 Calendar Wild Wild Web: Weekend Traveler: July Events: Head to the Stern Partying like it’s Two relaxing days in Grove Festival for a variety of top 1999 10 Laguna Beach 28 acts, or stay in the Marina to catch the band Future Bible Heroes, Food & Wine Pets head downtown to hear David Dishing: Kelsey Skylar Grey: Gergen, or catch the Cliff House’s Nixon Q&A 14 School time 30 150th anniversary 20 WWW.MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 27TH YEAR VOLUME 29 ISSUE 7 JULY 2013 Reynolds Rap The usual suspects Hypocrisy and questionable ethics mar Small Business Commission in pet store debate by susan dyer reynolds efore the June 10 meeting of the San Francisco Small Business Commission (SBC), I overheard Commissioner William Ortiz- Cartagena say he was recusing himself from an Bagenda item due to a past relationship with the landlord’s parking lot. I knew immediately he was talking about Pet Food Express (PFE) seeking a conditional use permit to move into the long-empty Blockbuster building at 2460 Ballet on the bay as Oracle Team USA practices PHOTO: © ACEA / PHOTO GILLES MARTIN-RAGET Lombard Street, but when I grabbed a copy of the agenda, PFE wasn’t listed. Then I got to number 8: “Presentation and possible action to support Pet Store merchants regard- ing their efforts to maintain their businesses.” The verbiage The battle on the bay stated that two pet stores on Chestnut Street were “work- ing to prevent their businesses from possible closure,” and by jim maxwell Racing’s AC72 boat capsized during become a real sticking point, with included five-minute presentations by Pam Hable of Catnip a training run on May 9.