Petitioner, V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nixon, in France,11

SEE STORY BELOW Becoming Clear FINAL Clearing this afternoon. Fair and cold tonight. Sunny., mild- Red Bulk, Freehold EIMTION er tomorrow. I Long Branch . <S« SeUdlf, Pass 3} Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 173 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 26 PAGES 10 CENTS ge Law Amendments Are Urged TRENTON - A legislative lative commission investigat- inate the requirement that where for some of die ser- the Monmouth Shore Refuse lection and disposal costs in Leader J. Edward CrabieJ, D- committee investigating the ing the garbage industry. there be unanimous consent vices tiie authority offers if Disposal Committee' hasn't its member municipalities, Middlesex, said some of the garbage industry yester- Mr. Gagliano called for among the participating the town wants to and the au- done any appreciable work referring the inquiry to the suggested changes were left day heard a request for amendments to the 1968 Solid municipalttes in the selection thority doesn't object. on the problems of garbage Monmouth County Planning out of the law specifically amendments to a 1968 law Waste Management Authority of a disposal site. He said the The prohibition on any par- collection "because we feel Board. last year because it was the permitting 21 Monmouth Saw, which permits the 21 committee might never ticipating municipality con- the disposal problem is funda- The Monmouth Shore Ref- only way to get the bill ap- County municipalities to form Monmouth County municipal- achieve unanimity on a site. tracting outside the authority mental, and we will get the use Disposal Committee will proved by both houses of the a regional garbage authority. -

{DOWNLOAD} No Lifeguard on Duty: the Accidental Life of the Worlds First Supermodel

NO LIFEGUARD ON DUTY: THE ACCIDENTAL LIFE OF THE WORLDS FIRST SUPERMODEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janice Dickinson | 320 pages | 10 Nov 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060009472 | English | New York, United States No Lifeguard on Duty: The Accidental Life of the Worlds First Supermodel PDF Book Nov 30, Ashley rated it did not like it Recommends it for: Everyone Sign In Don't have an account? Alter what I've been through, I don't think so, pal. One of the juiciest tell-all books ever! He was a dark, angry guy. British rocker Peter Frampton grew up fast before reaching meteoric heights with Frampton Comes Alive! She downplays her interactions with Bill Cosby in this book, which was published before metoo. Now a monk, he is forced to return to his dark and absurd childhood home to clear his name. Being that I am infatuated with the 70's and I had to take a break from all the death and dismemberment I've been reading about as of late, I bought a copy of her book, thinking it would be quick, light on-the-potty reading, full of fun gossipy tidbits about my favorite decade and all the beautiful people who were there. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez voting Twitch stream becomes one of platform's most-viewed. I find it both entertaining and educating. It also contains a scene in which Bill Cosby invites her back to his hotel room and she refuses him, a scene that she says Cosby's lawyers forced her to change. Janice Dickinson was born in in Brooklyn, NYC and is one of the most successful supermodels of all time. -

Janice Dickinson V. William H. Cosby, Jr. Case No. BC 580909 1 2 3 4 5 6

1 Lisa Bloom, Esq. (SBN 158458) Jivaka Candappa, Esq. (SBN 225919) 2 Alan Goldstein, Esq. (SBN 296430) 3 THE BLOOM FIRM 20700 Ventura Blvd., Suite 301 4 Woodland Hills, CA 91364 Telephone: (818) 914-7314 5 Facsimile: (866) 852-5666 6 Email: [email protected] Jivaka@TheBloomFirm 7 [email protected] 8 Attorneys for Plaintiff JANICE DICKINSON 9 10 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 11 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, CENTRAL DISTRICT 12 13 Case Number: BC 580909 JANICE DICKINSON, an individual, [Case assigned to The Honorable 14 Plaintiff, Debre Weintraub – Department 47] 15 v. 16 PLAINTIFF JANICE DICKINSON’S WILLIAM H. COSBY, JR., an individual OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANT’S 17 Defendant. SPECIAL MOTION TO STRIKE 18 PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT 19 Date: February 29, 2016 20 Time: 8:30 A.M. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 PLAINTIFF JANICE DICKINSON’S OPPOSITION Janice Dickinson v. William H. Cosby, Jr. Case No. BC 580909 THE BLOOM FIRM 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Page 3 I. INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………………………...1 4 II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND.………………………………………………………………….1 5 A. MR. COSBY DRUGGED AND RAPED MS. DICKINSON IN OR ABOUT 1982.……………1 6 B. MS. DICKINSON’S PRIOR DISCLOSURES OF THE RAPE, 1982-2010.………………….....1 7 C. MS. DICKINSON PUBLICLY DISCLOSES THE RAPE ………………………………………2 8 D. MR. COSBY QUICKLY RETALIATES BY DEFAMING MS. DICKINSON.………..............2 9 E. MR. COSBY REFUSES TO RETRACT THE FALSE STATEMENTS.…………………...........2 10 F. MR. COSBY ADMITS UNDER OATH TO DRUGGING WOMEN FOR SEX.………………..2 11 III. LEGAL ARGUMENT.…………………………………………………………………………3 12 A. DEFENDANT MUST SATISFY BOTH PRONGS OF THE ANTI-SLAPP STATUTE.……….3 B. -

Upreme Qtourt of Tbe Mlniteb Tateg

Case No. INTHE �upreme Qtourt of tbe mlniteb �tateg William H. Cosby, Jr. Petitioner, V. Janice Dickinson Respondent. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT Application for Extension of time to file a Petition fora Writ of Certiorari GREENBERG GROSS LLP Counsel of Record BECKY S. JAMES 601 S. Fir,ueroa Street 3011 Floor Los Angeles, CA 90017 (213) 334-7000 Counsel for William H. Cosby, Jr. APPLICATION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO FILE A PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI To: Hon. Anthony Kennedy, Circuit Justice for the Ninth Circuit: Under this Court's rules 13.5 and 22, Applicant William Henry Cosby, Jr. respectfully requests a 30-day extension to file his Petition for Writ of Certiorari. In support of this application, Applicant states: 1. Applicant intends to seek review of the decision of the California Court of Appeal in Dickinson v. Cosby, 17 Ca. App. 5th 655 (Nov. 21, 2017), review denied (Mar. 14, 2018), a copy of which is annexed hereto. Applicant's Petition forReview to the California Supreme Court was denied on March 14, 2018. Absent the requested extension of time, a petition for writ of certiorari would be due on June 12, 2018. Applicant requests that. the time for filingbe extended by 30 days, to and including July 12, 2018. 2. This decision - as a petition forwrit of certiorari will develop more fully- is a serious candidate forthis Court'sreview: a. The California Court of Appeal's decision implicates serious First Amendment concerns. In 2014, Janice Dickinson publicly claimed that Applicant, William H. -

Testimony of Janice Dickinson

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF MONTGOMERY, PENNSYLVANIA CRIMINAL DIVISION COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA: vs. NO. 3932-16 WILLIAM H. COSBY, JR. TESTIMONY OF JANICE DICKINSON Courtroom A Thursday, April 12, 2018 Commencing at 11:27 a.m. Virginia M. Womelsdorf, RPR Official Court Reporter Montgomery County Courthouse Norristown, Pennsylvania BEFORE: THE HONORABLE STEVEN T. O'NEILL, JUDGE AND A JURY COUNSEL APPEARED AS FOLLOWS: KEVIN R. STEELE, ESQUIRE District Attorney M. STEWART RYAN, ESQUIRE KRISTEN GIBBONS-FEDEN, ESQUIRE Assistant District Attorneys for the Commonwealth LANE L. VINES, ESQUIRE THOMAS A. MESEREAU, JR., ESQUIRE KATHLEEN BLISS, ESQUIRE JASON HICKS, ESQUIRE BECKY S. JAMES, ESQUIRE RACHAEL ROBINSON, ESQUIRE JAYA GUPTA, ESQUIRE for the Defendant ALSO PRESENT: JONATHAN PERRONE, Computer Operations Supervisor Montgomery County District Attorney's Office INDEX COMMONWEALTH'S EVIDENCE Witness VDire Direct Cross Redir Recr JANICE DICKINSON 4 37 83 EXHIBITS COMMONWEALTH'S Number Description Marked Rec'd C-11 Photograph 19 20 C712 Photograph 19 20 C-13 Photograph 19 20 C-14 Declaration of Pablo Fenjvez 87 Ct-15 Declaration of Judith Regan 94 4 1 JANICE DICKINSON - DIRECT 2 THE COURT: Okay. You may call your 3 next witness. 4 MR. RYAN: Thank you, Your Honor. 5 Janice Dickinson. 6 - - - 7 JANICE DICKINSON, having been duly 8 sworn, was examined and testified as 9 follows: 10 DIRECT EXAMINATION 11 By MR. RYAN: 12 Q Good morning, Janice. 13 A Good morning. 14 Q Can you tell me where you live? 15 A I live in Tarzana, California. 16 Q And who do you live with? 17 My husband, Rocky Gerner. -

IMPORTING the FLAWLESS GIRL Kit Johnson*

IMPORTING THE FLAWLESS GIRL Kit Johnson* ABSTRACT ......................................................... 831 I. THE NEED FOR FOREIGN MODELS ............................ 832 II. HOW THE MODELING INDUSTRY WORKS ...................... 835 A. The Place of Fashion Models within Modeling ........... 835 B. How Fashion Models are Booked and Paid .............. 836 C. How Foreign Models Differ from U.S. Models ............ 839 III. FASHION MODEL VISAS TODAY .............................. 840 A. H1B History ........................................... 841 B. When Models Re-Joined the Picture ..................... 843 C. Distinguished Merit and Ability.......................... 845 1. The Models ........................................ 845 2. The Work .......................................... 846 3. The Agencies ....................................... 847 4. Duration ........................................... 848 IV. BEAUTY AND THE GEEK ..................................... 848 V. THE UGLY AMERICAN BILL .................................. 850 A. A New Classification for Models......................... 851 B. The High Heeled and the Well Heeled ................... 854 1. Value .............................................. 854 2. Interchangeability .................................. 856 VI. CHANGING THE FACE OF THE FLAWLESS GIRL ................. 857 A. The P(x) Visa for Models of the Moment ................. 858 B. An H1(x) Visa for Artisan Models ....................... 858 1. Size ............................................... 859 2. Age............................................... -

In the Supreme Court of California

S246185 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA JANICE DICKINSON, Plaintiff and Appellant, v. WILLIAM H. COSBY, JR., Defendant and Appellant, MARTIN D. SINGER, Defendant and Respondent. AFTER A DECISION BY THE COURT OF APPEAL, SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT, DIVISION EIGHT, CASE NO. B271470 PETITION FOR REVIEW GREENBERG GROSS LLP ALAN A. GREENBERG (BAR NO. 150827) WAYNE R. GROSS (BAR NO. 138828) *BECKY S. JAMES (BAR NO. 151419) 601 S. Figueroa Street, 30th Floor Los Angeles, California 90017 (213) 334-7000 • FAX: (213) 334-7001 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANT AND APPELLANT WILLIAM H. COSBY, JR. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ISSUES PRESENTED .................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION AND REASONS FOR GRANTING REVIEW............. 9 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................................... 13 A. Dickinson’s 2002 Autobiography States She Did Not Engage in Sexual Conduct with Cosby ................................. 13 B. In Late 2014, Dickinson Changes Her Story to Accuse Cosby of Rape ....................................................................... 13 C. Cosby’s Attorney Responds to These New Allegations ....... 14 1. The November 18 Letter ............................................ 14 2. The November 19 Press Statement ............................ 15 D. Dickinson Sues Cosby Based on Singer’s Statements, and Cosby Responds with an Anti-SLAPP Motion .............. 15 E. The Court of Appeal Concludes that -

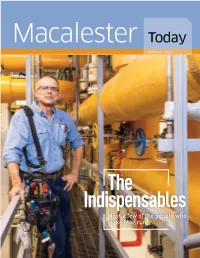

Download Issue PDF the Winter 2015 Issue Of

Macalester Today WINTER 2015 The Indispensables Meet a few of the people who make Mac run. PAGE 16 Macalester Today WINTER 2015 Features Crisis Connection 10 At CaringBridge, a nonprofit that allows ailing people to communicate with friends, two Mac alums are making 10 a difference. Bard of Rock 12 The life and times of music writer Charles M. Young ’73 The Indispensables 16 Meet a few of the people who make Mac run Refugee Responder 22 Megan Garrity ’08 is devoting her life to helping Syrian refugees. 50 Years of Jan 24 Janice Dickinson ’64 loved Macalester College so much she never left. Now, after half a century working for Mac, 16 she’s retiring. Here’s what those years have looked like. Macalester Yesterday 26 Excerpts from interviews in the Macalester College Archives Consent is Mac 32 With a crisis in college sexual assaults sparking national debate, how to create a campus-wide culture of consent? ON THE COVER: Ed Gerten, veteran Macalester electrician (Photo by David J. Turner) 22 (TOP TO BOTTOM): STEVE NIEDORF ’72, DAVID J. TURNER, COURTESY OF MEGHAN GARRITY ’08 Staff EDITOR Lynette Lamb [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Brian Donahue CLASS NOTES EDITOR Robert Kerr ’92 PHOTOGRAPHER David J. Turner CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Rebecca DeJarlais Ortiz ’06 Jan Shaw-Flamm ’76 DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS David Warch MACALESTER COLLEGE CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES David Deno ’79 PHOTO: STEVE WARMOWSKI PHOTO: 4 PRESIDENT Brian Rosenberg DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS Departments Gabrielle Lawrence ’73 Letters 2 MACALESTER TODAY (Volume 103, Number 1) Household Words 3 is published by Macalester College. -

The Changing Contours of Africa's Security Governance

Review of African Political Economy No.118:539-553 © ROAPE Publications Ltd., 2008 Public/Private, Global/Local: The Changing Contours of Africa’s Security Governance Rita Abrahamsen & Michael C. Williams From conflict zones to shopping malls, from resource extraction sites to luxury tourist enclaves, private security has become a ubiquitous feature of modern life. While the ‘monopoly of legitimate violence’ continues to be one of the defining features of state sovereignty, and one of the most powerful elements of the modern political imagination, the realities of security today increasingly transcend its confines, and include a wide range of private actors. At its most controversial, private security is represented by the combat active soldier, heavily armed and actively involved in warfare. At its most mundane, it involves the unarmed guard at a hotel entrance, or a neighbourhood watch of concerned citizens mobilising local energies in the pursuit of safety and security. Africa is, of course, no stranger to these various forms of private security, although it is fair to say that to date, the military dimension has dominated discussion. The infamous activities of mercenaries such as Bob Denard and ‘Mad’ Mike Hoare in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the more distant exploits of Cecil Rhodes and the privately-financed armies of his commercial empire, mean that Africa easily lends itself to portrayal as the natural environment for rapacious and ruthless forms of entrepreneurship and control in which private gain is intimately and directly linked to the ability to wield private violence. More recent spectacular actions, such as Executive Outcomes’ (EO) intervention in Sierra Leone in the 1990s and Simon Mann’s aborted coup attempt in Equatorial Guinea in 2004 only reinforce this image of Africa as the chosen playground of the world’s soldiers of fortune. -

List of Errors Something Personal

Avedon: Something Personal, list of errors in formation in consecutive order 1 1. Revlon’s “Wine with Everything” (with Rene Russo) is years later than this 1975/6 New Year’s Eve time period. 2. Avedon did not have “silvery” hair in this time period (1975). From his 1975 passport: hair “black” with accompanying photo. 3. The whole 1975/6 New Year’s Eve scene in the book is counter to Stevens’ 2009 recorded oral history that she recorded for The Richard Avedon Foundation. 4. Avedon did not have a personal relationship with Marilyn Monroe, nor did he have her personal phone numbers (though he did have fictitious ones – from his novel). 5. The Almay model from the late 1960s is not Swedish, and Norma Stevens (then Norma Gottlieb Bodine) did not participate on any Almay shoot with Avedon in the late 1960s. 6. Stevens’ positive response to the Saran Wrapped model in the book is 100% counter to her 2009 recorded account (“it was just horrible and the client hated it, and I hated it.” 7. Suzy Parker’s was not the first belly button in an American high fashion magazine. 8. Christina Paolozzi’s bared breasts were not the first in an American high fashion magazine – not even for Avedon. 9. Naty and Ana-Maria Abascal were not part of a ménage à trois (they are twin sisters). 10. donyale Luna is not the first haute-couture “black beauty,” not even for Avedon. 11. With regard to Stevens’ “innumerable” Avedons she claims she owns, this statement runs counter to legal testimony she gave during an Avedon Foundation forensic audit in 2009 claiming that she owned almost no Avedons. -

A Contemporary Perspective

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 106 214 SO 008 369 AUTHOR Mnessig, Raymond B., Ed. TITLE Controversial Issues in the Social Studies: A Contemporary Perspective. 45th Yearbook, 1975. INSTITUTION National Council for the Social Studies, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 305p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council for the Social Studies, 1201 Sixteenth Street, N.V., Washington, D.C. 20036 ($8.75) EDRS PRICE MF-S0.76 EC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Academic Freedom; Course Content; Critical Thinking; Cultural Pluralism; Death; Educational Improvement; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; Environmental Education; Sex Education; Social Attitudes; *Social Problems; *Social Studies; *Teaching Methods; *Values; Yearbooks IDENTIFIERS *Controversial Issues ABSTRACT This Yearbook is an expression of the National Council for the Social Studies' conviction that social studies teachers need to recognize their responsibility for introducing controversial issues into the classroom: Examination of social problems serve as a means to teach studdsts how to think, rather than what to think, so that students will be able to assume the responsibility of democratic citizenship,'" Critical thinking skills can be taught by examining the problems inherent in a democratic society. Background materials and sone teaching suggestions are presented to the teacher for dealing successfully with social problems in the classroom. Part one of the docnsent provides theoretical and practical aspects of handling controversial issues, including teacher preparation and models. Part two offers examples of specific areas of controversy. Chapter titles include "Should Traditional Sex Models and Values Be Changed"; "Should the Study of Death Be a Necessary Preparation for Living"; "Should the Majority Rule"; "Should Integration be a Societal Goal in a Pluralistic Nation"; "Should We Believe That Our Planet is in Peril"; and "Should the Nation-State Give Way to Some Form of World Organization?- (Author/JR) il'iretlieiSbola-).&pp AI., .At .igetiodetivvi A,. -

Media, Entertainment and Technology Group - 2018 Mid-Year Update

August 8, 2018 MEDIA, ENTERTAINMENT AND TECHNOLOGY GROUP - 2018 MID-YEAR UPDATE To Our Clients and Friends: For our latest semi-annual update, Gibson Dunn's Media, Entertainment and Technology practice group is taking stock of another active period of deals, regulatory developments, and litigation. The first half of 2018 has been marked by landmark M&A, esports growth, precedent-setting copyright cases, an end to the "Blurred Lines" saga, and some clarity from California and New York courts in anticipated right of publicity cases. And we have seen courts wrestling with twenty-first century legal issues raised by terms like geoblocking, top-level domains, Simpsonizing, and embedded Tweets. Here, then, is our latest round-up to bring you current on the deals and decisions that will hold lessons for the months and years to come. I. Transaction Overview A. M&A 1. AT&T and Time Warner Prevail in Antitrust Suit and Complete Merger On June 12, 2018, in a 172-page decision following a six-week trial, U.S. District Judge Richard J. Leon denied the government's request to enjoin the proposed merger between AT&T and Time Warner, and the companies completed the merger two days later, bringing together the content produced by Warner Bros., HBO and Turner with AT&T's mobile, broadband, video and other communications services.[1] "Our merger brings together the elements to fulfill our vision for the future of media and entertainment," AT&T said in a press release.[2] On July 12, the government filed a notice of appeal.[3] (Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represents AT&T and DirecTV in the case.) 2.