LINCOLN STEFFENS DOCUMENT #1 Lincoln Steffens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln Steffens: "The Shame of Minneapolis."

THE SHAME OF MINNEAPOLIS : The Ruin and Redemption of a City that was Sold Out. By Lincoln Steffens _____ With an Introduction by Mark Neuzil, Ph.D. Lincoln Steffens in 1914 1 Minneapolis and the Muckrakers: Lincoln Steffens and the Rise of Investigative Journalism * By Mark Neuzil, Ph.D. ** The muckraking era in American history is generally thought of as beginning in about 1902 and lasting until the end of the Taft administration or the beginning of World War One, depending on which historian you read. Muckraking, in terms of journalism history, is thought of as a crusading, reform-oriented style of the craft that fathered the investigative reporting of modern times, from Watergate to current issues. One of the most significant early muckraking stories happened here in Minneapolis, and although it is sometimes overlooked in the general journalism histories of the time, it remains important to our understanding of how the field evolved. The story was titled “The Shame of Minneapolis: The Ruin and Redemption of a City that was Sold Out,” and it ___________ * An earlier version of this paper was delivered on October 5, 2003, to an audience at the Mill City Museum in Minneapolis. It was revised by the author in September 2011, for the MLHP . ** Mark Neuzil received his doctorate from the University of Minnesota in 1993. He was a reporter for several years for many newspapers, including the Minneapolis Star Tribune . In 1993, he joined the Department of Communication and Journalism at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul. His publications include: Mass Media and Environmental Conflict: America's Green Crusades (Sage, 1996) co-authored with William Kovarik; Views of the Mississippi: The Photographs of Henry Bosse (Minnesota, 2001), which won a Minnesota Book Award; A Spiritual Field Guide; Meditations for the Outdoors (Brazos Press, 2005), co-authored with Bernard Brady; and The Environment and the Press: From Adventure Writing to Advocacy (Northwestern University Press, 2008). -

Clara E. Sipprell Papers

Clara E. Sipprell Papers An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University Finding aid created by: - Date: unknown Revision history: Jan 1984 additions, revised (ASD) 14 Oct 2006 converted to EAD (AMCon) Feb 2009 updated, reorganized (BMG) May 2009 updated 87-101 (MRC) 21 Sep 2017 updated after negative integration (SM) 9 May 2019 added unidentified and "House in Thetford, Vermont" (KD) extensively updated following NEDCC rehousing; Christensen 14 May 2021 correspondence added (MRC) Overview of the Collection Creator: Sipprell, Clara E. (Clara Estelle), 1885-1975. Title: Clara E. Sipprell Papers Dates: 1915-1970 Quantity: 93 linear ft. Abstract: Papers of the American photographer. Original photographs, arranged as character studies, landscapes, portraits, and still life studies. Correspondence (1929-1970), clippings, interviews, photographs of her. Portraits of Louis Adamic, Svetlana Allilueva, Van Wyck Brooks, Pearl S. Buck, Rudolf Bultmann, Charles E. Burchfield, Fyodor Chaliapin, Ralph Adams Cram, W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Ralph E. Flanders, Michel Fokine, Robert Frost, Eva Hansl, Roy Harris, Granville Hicks, Malvina Hoffman, Langston Hughes, Robinson Jeffers, Louis Krasner, Serge Koussevitzky, Luigi Lucioni, Emil Ludwig, Edwin Markham, Isamu Noguchi, Maxfield Parrish, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dane Rudhyar, Ruth St. Denis, Otis Skinner, Ida Tarbell, Howard Thurman, Ridgely Torrence, Hendrik Van Loon, and others Language: English Repository: Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries 222 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, NY 13244-2010 http://scrc.syr.edu Biographical History Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) was a Canadian-American photographer known for her landscapes and portraits of famous actors, artists, writers and scientists. Sipprell was born in Ontario, Canada, a posthumous child with five brothers. -

Not for Publication:__ Vicinity

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 IDA TARBELL HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registrauon Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Ida Tarbell House Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 320 Valley Road Not for publication:__ . City/Town: Easton Vicinity:__ State: CT County: Fairfield Code: 001 Zip Code: 06612 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 1 buildings ____ sites 1 structures ____ objects 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 IDA TARBELL HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Radicalism and the Limits of Reform: the Case of John Reed

DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 RADICALISM AND THE LIMITS OF REFORM: THE CASE OF JOHN REED Robert A. Rosenstone To be published in a volume of essays honoring George Mowry HUMANITIES WORKING PAPER 52 September 1980 ABSTRACT Poet, journalist, editorial bo,ard member of the Masses and founding member of the Communist Labor Party, John Reed is a hero in both the worlds of cultural and political radicalism. This paper shows how his development through pre-World War One Bohemia and into left wing politics was part of a larger movement of middle class youngsters who were in that era in reaction against the reform mentality of their parent's generation. Reed and his peers were critical of the following, common reformist views: that economic individualism is the engine of progress; that the ideas and morals of WASP America are superior to those of all other ethnic groups; that the practical constitutes the best approach to social life. By tracing Reed's development on these issues one can see that his generation was critical of a larger cultural view, a system of beliefs common to middle class reformers and conservatives alike. Their revolt was thus primarily cultural, one which tested the psychic boundaries, the definitions of humanity, that reformers shared as part of their class. RADICALISM AND THE LIMITS OF REFORM: THE CASE OF JOHN REED Robert A. Rosenstone In American history the name John Reed is synonymous with radicalism, both cultural and political. Between 1910 and 1917, the first great era of Bohemianism in this country, he was one of the heroes of Greenwich Village, a man equally renowned as satiric poet and tough-minded short story writer; as dashing reporter, contributing editor of the Masses, and co-founder of the Provinceton Players; as lover of attractive women like Mabel Dodge, and friend of the notorious like Bill Haywood, Enma Goldman, Margaret Sanger and Pancho Villa. -

Biography Activity: Ida Tarbell

NAME _______________________________________________ CLASS ___________________ DATE _________________ BIOGRAPHY Ida Tarbell Among the muckrakers of the Progressive Era, none surpassed the careful reporting, clever pen, and moral outrage of Ida Tarbell. She took on the nation’s most powerful trust—Standard Oil—and its creator—the nation’s wealthiest man, John D. Rockefeller—in 18 installments of McClure’s magazine. As you read, think about how Ida Tarbell’s writing influenced her country’s history. Ida Tarbell developed her moral outrage at the and her experience with Standard Oil, McClure Standard Oil trust through personal family expe- assigned her to the story. Her father, recalling the rience. Soon after her birth in 1857 on a farm in trust’s ruthless tactics, pleaded, “Don’t do it, Ida.” Pennsylvania, oil was discovered in nearby Titus- Others also tried to warn her away from the trust’s ville. Her father, Franklin, saw an opportunity to “all-seeing eye and the all-powerful reach,” pre- make money in this promising new field. He became dicting, “they’ll get you in the end,” but Tarbell the first manufacturer of wooden tanks for the oil would not be stopped. For the next two years, she industry and established a prosperous business. researched the business practices of Standard Oil In time, however, the Standard Oil Company and then began writing her series. In the first began to force other oil suppliers out of business. installment, she described the hope, confidence, Standard Oil became Franklin’s only client, and and energy of pioneer oil men. “But suddenly, at refused to pay his prices. -

Chapter 18 Video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” Portrays the Horrors of the Meatpacking Industry First Investigated by Upton Sinclair

The Progressive Movement 1890–1919 Why It Matters Industrialization changed American society. Cities were crowded with new immigrants, working conditions were often bad, and the old political system was breaking down. These conditions gave rise to the Progressive movement. Progressives campaigned for both political and social reforms for more than two decades and enjoyed significant successes at the local, state, and national levels. The Impact Today Many Progressive-era changes are still alive in the United States today. • Political parties hold direct primaries to nominate candidates for office. • The Seventeenth Amendment calls for the direct election of senators. • Federal regulation of food and drugs began in this period. The American Vision Video The Chapter 18 video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” portrays the horrors of the meatpacking industry first investigated by Upton Sinclair. 1889 • Hull House 1902 • Maryland workers’ 1904 opens in 1890 • Ida Tarbell’s History of Chicago compensation laws • Jacob Riis’s How passed the Standard Oil the Other Half Company published ▲ Lives published B. Harrison Cleveland McKinley T. Roosevelt 1889–1893 ▲ 1893–1897 1897–1901 1901–1909 ▲ ▲ 1890 1900 ▼ ▼ ▼▼ 1884 1900 • Toynbee Hall, first settlement • Freud’s Interpretation 1902 house, established in London of Dreams published • Anglo-Japanese alliance formed 1903 • Russian Bolshevik Party established by Lenin 544 Women marching for the vote in New York City, 1912 1905 • Industrial Workers of the World founded 1913 1906 1910 • Seventeenth 1920 • Pure Food and • Mann-Elkins Amendment • Nineteenth Amendment Drug Act passed Act passed ratified ratified, guaranteeing women’s voting rights ▲ HISTORY Taft Wilson ▲ ▲ 1909–1913 ▲▲1913–1921 Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1910 1920 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 18 to preview chapter information. -

Press Conference at the National Women's Hall of Fame of Hon

10-07-00: PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL...NET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES NEW YORK PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL OF FAME OF HON. JANET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES Saturday, October 7, 2000 New York Chiropractic College Athletic Center 2360 State Route 89 Seneca Falls, New York 9:38 a.m. P R O C E E D I N G S CHAIR SANDRA BERNARD: Good morning and welcome to the National Women's Hall of Fame Honors Weekend and Induction Ceremony. I am Sandra Bernard, Chair of the weekend's events. Today, before a sell-out crowd, we will induct 19 remarkable women into the Hall of Fame. Now, those of you who are history buffs may know that the idea to form a Hall to honor, in perpetuity, the contributions to society of American women started, like so many other good things in Seneca Falls have, over tea. And just like the tea party that spawned the Women's Rights Convention, the concept of a National Women's Hall of Fame was an idea whose time has come. http://www.usdoj.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2000/10700agsenecafalls.htm (1 of 11) [4/20/2009 1:10:27 PM] 10-07-00: PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL...NET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES NEW YORK Our plans for the morning are to tell you a bit more about the mission, the moment and the meaning, and then to introduce you to the inductees. -

Unit 5- an Age of Reform

Unit 5- An Age of Reform Important People, Terms, and Places (know what it is and its significance) Civil service Gilded Age Primary Recall Initiative Referendum Muckraker Theodore Roosevelt Susan B Anthony Conservation William Howard Taft Jane Addams Woodrow Wilson Carrie Chapman Catt Suffragist Ida Tarbell Frances Willard Upton Sinclair Prohibition Temperance Lucretia Mott Carrie Nation Jacob Riis Booker T Washington W.E.B Dubois Robert LaFollette The Progressive Party 16th Amendment Spoils System Thomas Nast You should be able to write an essay discussing the following: 1. What were political reforms of the period that increased “direct” democracy? 2. The progressive policies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. How did they expand the power of the federal government? 3. The role of the Muckrakers in creating change in America 4. Summarize the other reform movements of the Progressive era. 5. What was the impact of the Progressive Movement on women and blacks? 6. Compare and contrast the beliefs of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B Dubois Important Dates to Remember 1848 – Declaration of Sentiments written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton 1874 – Woman’s Christian Temperance Union formed. 1889 – Jane Addams founds Hull House 1890 – Jacob Riis publishes “How the Other Half Lives” 1895 – Anti Saloon League founded 1904 – Ida Tarbell publishes “The History of Standard Oil” 1906 – Upton Sinclair publishes “The Jungle” 1906 – Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act passed 1909 – National Association for the Advancement of Colored People founded. (NAACP) 1913 – 16th Amendment passed 1914 – Clayton Anti-Trust Act passed 1919 – 18th Amendment passed (prohibition) 1920 – 19th Amendment passed (women’s suffrage) . -

Lesson Five: Families in the Mansion

Lesson Five: Families in the Mansion Objectives Students will be able to: ¾ Understand the purpose and function of the original mansion built on the corner of 16th and H Streets, Sacramento ¾ Explain the lives of the private families who lived in the mansion ¾ Describe life at the mansion from the perspective of the governors and their families who lived there Governor’s Mansion State Historic Park – California State Parks 41 Lesson Five: Families in the Mansion Governor’s Mansion State Historic Park – California State Parks 42 Lesson Five: Families in the Mansion Pre-tour Activity 1: The Thirteen Governors and Their Families Materials ; Handouts on each of the thirteen governors and their families ; Map of the United States (either a classroom map or student copies) ; “The Thirteen Governors and Their Families” worksheet Instructional Procedures 1. Explain to the students that we learn about history by reading and thinking about the lives of people who lived before us. True life stories about people are called biographies. Have the class read the governors’ biographies. As they read they should consider the following questions: Where was the governor raised? Who was his wife? How many children did they have? What was it like to be the son or daughter of the governor? What did the governor do before he became governor? In what ways did the governor’s family make the Governor’s Mansion a home? 2. Explain to the students that most of the governors were not born in California. On the United States map identify the city or state where each governor was raised and his family was from. -

Suffrage Organizations Chart.Indd

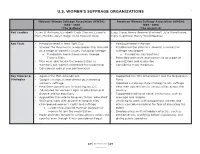

U.S. WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE ORGANIZATIONS 1 National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), 1869 - 1890 1869 - 1890 “The National” “The American” Key Leaders Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Lucy Stone, Henry Browne Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, Mott, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Anna Howard Shaw Mary Livermore, Henry Ward Beecher Key Facts • Headquartered in New York City • Headquartered in Boston • Started The Revolution, a newspaper that focused • Established the Woman’s Journal, a successful on a range of women’s issues, including suffrage suffrage newspaper o Funded by a pro-slavery man, George o Funded by subscriptions Francis Train • Permitted both men and women to be a part of • Men were able to join the organization as organization and leadership members but women controlled the leadership • Considered more moderate • Considered radical and controversial Key Stances & • Against the 15th Amendment • Supported the 15th Amendment and the Republican Strategies • Sought a national amendment guaranteeing Party women’s suffrage • Adopted a state-by-state strategy to win suffrage • Held their conventions in Washington, D.C • Held their conventions in various cities across the • Advocated for women’s right to education and country divorce and for equal pay • Supported traditional social institutions, such as • Argued for the vote to be given to the “educated” marriage and religion • Willing to work with anyone as long as they • Unwilling to work with polygamous women and championed women’s rights and suffrage others considered radical, for fear of alienating the o Leadership allowed Mormon polygamist public women to join the organization • Employed less militant lobbying tactics, such as • Made attempts to vote in various places across the petition drives, testifying before legislatures, and country even though it was considered illegal giving public speeches © Better Days 2020 U.S. -

5, Webisode 10

Please note: Each segment in this Webisode has its own Teaching Guide The muckrakers had a good friend in Sam McClure. He founded McClure’s Magazine, which set a new standard for activist journalism and created a new field, investigative journalism. Most important, he hired the best writers he could find: Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens, Jack London, Booth Tarkington, Rudyard Kipling, Stephen Crane, and Willa Cather. Ida Tarbell broke new ground not only in showing what a woman could do in a traditionally male occupation but also in setting a standard for scholarship, fairness, and integrity in the new field of investigative journalism. Her painstakingly researched The History of the Standard Oil Company detailed the illegal tactics used by John D. Rockefeller and led to the 1911 Supreme Court decision to break up the Standard Oil trust. Another female muckraker, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, got her first job at a newspaper at age nineteen; by twenty-five, she was the most famous woman in the world, known as the daring round-the-world reporter Nellie Bly. Editor Sam McClure and energetic journalists exercised their First Amendment right and used the pen to expose the excesses of the Gilded Age. They gave birth to the field of investigative journalism. Teacher Directions 1. Ask students to predict. • From what you know about the last half of the nineteenth century, what problems might newspaper writers expose? 2. Allow time for student response. 3. Make sure students understand the following points in discussing the question. In the Gilded Age, industry boomed and large corporations grew. -

Muckraking: a Dirty Job with Clean Intentions Courtney E

The Histories Volume 7 | Issue 2 Article 2 Muckraking: A Dirty Job with Clean Intentions Courtney E. Bowers La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Courtney E. () "Muckraking: A Dirty Job with Clean Intentions," The Histories: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories/vol7/iss2/2 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH stories by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Histories, Volume 7, Number 2 2 I. Muckraking: A Dirty Job with Clean Intentions By Courtney E. Bowers ‘08 There is nothing more interesting to people than other people. The plethora of tabloids and morning discussions over who has broken up with whom attest to this fact. People love to read about the gripping stories of other people’s lives, especially when their own seem so boring and unexciting. They love the triumphs of a hard battle won, of a good turnout against all odds. But they love the darker side of humanity even more— hearing about thievery and calumny and murder and all the foibles of the lives of the rich, famous and powerful. In a sense, it is a way of “sticking it to the man,” as the saying goes. Such stories show opportunities that the average man will never have, and how they blew up in the face of those who misused them.