The Development of an Archive of Explicit Stylistic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New International Manual of Braille Music Notation by the Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union

1 New International Manual Of Braille Music Notation by The Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union Compiled by Bettye Krolick ISBN 90 9009269 2 1996 2 Contents Preface................................................................................ 6 Official Delegates to the Saanen Conference: February 23-29, 1992 .................................................... 8 Compiler’s Notes ............................................................... 9 Part One: General Signs .......................................... 11 Purpose and General Principles ..................................... 11 I. Basic Signs ................................................................... 13 A. Notes and Rests ........................................................ 13 B. Octave Marks ............................................................. 16 II. Clefs .............................................................................. 19 III. Accidentals, Key & Time Signatures ......................... 22 A. Accidentals ................................................................ 22 B. Key & Time Signatures .............................................. 22 IV. Rhythmic Groups ....................................................... 25 V. Chords .......................................................................... 30 A. Intervals ..................................................................... 30 B. In-accords .................................................................. 34 C. Moving-notes ............................................................ -

Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary

L , - 0 * 3 7 * 7 w NUI MAYNOOTH OII» c d I »■ f£ir*«nn WA Huad Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary John J. Feeley Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music (Performance) 3 Volumes Volume 1: Text Department of Music NUI Maynooth Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Supervisor: Dr. Barra Boydell May 2007 VOLUME 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 13 APPROACHES TO GUITAR COMPOSITION BY IRISH COMPOSERS Historical overview of the guitar repertoire 13 Approaches to guitar composition by Irish composers ! 6 CHAPTER 2 31 DETAILED DISCUSSION OF SEVEN SELECTED WORKS Brent Parker, Concertino No. I for Guitar, Strings and Percussion 31 Editorial Commentary 43 Jane O'Leary, Duo for Alto Flute and Guitar 52 Editorial Commentary 69 Jerome de Bromhead, Gemini 70 Editorial Commentary 77 John Buckley, Guitar Sonata No. 2 80 Editorial Commentary 97 Mary Kelly, Shard 98 Editorial Commentary 104 CONTENTS CONT’D John McLachlan, Four pieces for Guitar 107 Editorial Commentary 121 David Fennessy, ...sting like a bee 123 Editorial Commentary 134 CHAPTER 3 135 CONCERTOS Brent Parker Concertino No. 2 for Guitar and Strings 135 Editorial Commentary 142 Jerome de Bromhead, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 148 Editorial Commentary 152 Eric Sweeney, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 154 Editorial Commentary 161 CHAPTER 4 164 DUOS Seoirse Bodley Zeiten des Jahres for soprano and guitar 164 Editorial -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands An

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands and demonstrates appropriate playing posture without prompts OR.PP.2 Understands and demonstrates correct finger/hand position without prompts OR.AR Articulation OR.AR.1 Interprets and performs combinations of bowing at an advanced level [tie, slur, staccato, hooked bowings, loure (portato) bowing, accent, spiccato, syncopation, and legato] OR.AR.2 Interprets and performs Ricochet, Sul Ponticello, and Sul Tasto bowings at a beginning level OR.TQ Tone Quality OR.TQ.1 Produces a characteristic tone at the medium-advanced level OR.TQ.2 Defines and performs proper ensemble balance and blend at the medium-advanced level OR.RT Rhythm/Tempo OR.RT.1 Defines and performs rhythm patterns at the medium-advanced level (quarter note/rest, half note/rest, eighth note/rest, dotted eighth note, dotted half note, whole note/rest, dotted quarter note, sixteenth note) OR.RT.2 Defines and performs tempo markings at a medium-advanced level (Allegro, Moderato, Andante, Ritardando, Lento, Andantino, Maestoso, Andante Espressivo, Marziale, Rallantando, and Presto) OR.TE Technique OR.TE.1 Performs the pitches and the two-octave major scales for C, G, D, A, F, Bb, Eb; performs the pitches and the two-octave minor scales for A, E, D, G, C; performs the pitches and the one-octave chromatic scale OR.TE.2 Demonstrates and performs pizzicato, acro, and left-hand pizzicato at the medium-advanced level OR.TE.3 Demonstrates shifting at the intermediate -

Plainchant Tradition*

Some Observations on the "Germanic" Plainchant Tradition* By Alexander Blachly Anyone examining the various notational systems according to which medieval scribes committed the plainchant repertory to written form must be impressed both by the obvious relatedness of the systems and by their differences. There are three main categories: the neumatic notations from the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries (written without a staff and incapable, therefore, of indicating precise pitches);1 the quadratic nota tion in use in Italy, Spain, France, and England-the "Romanic" lands from the twelfth century on (this is the "traditional" plainchant notation, written usually on a four-line staff and found also in most twentieth century printed books, e.g., Liber usualis, Antiphonale monasticum, Graduale Romanum); and the several types of Germanic notation that use a staff but retain many of the features of their neumatic ancestors. The second and third categories descended from the first. The staffless neumatic notations that transmit the Gregorian repertory in ninth-, tenth-, and eleventh-century sources, though unlike one another in some important respects, have long been recognized as transmitting the same corpus of melodies. Indeed, the high degree of concordance between manuscripts that are widely separated by time and place is one of the most remarkable aspects the plainchant tradition. As the oldest method of notating chant we know,2 neumatic notation compels detailed study; and the degree to which the neumatic manuscripts agree not only • I would like to thank Kenneth Levy, Alejandro Plan chart, and Norman Smith for reading this article prior to publication and for making useful suggestions for its improve ment. -

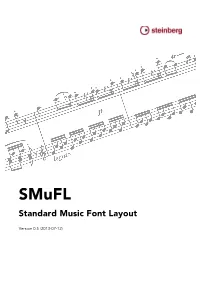

Standard Music Font Layout

SMuFL Standard Music Font Layout Version 0.5 (2013-07-12) Copyright © 2013 Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH Acknowledgements This document reproduces glyphs from the Bravura font, copyright © Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH. Bravura is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://www.smufl.org/fonts This document also reproduces glyphs from the Sagittal font, copyright © George Secor and David Keenan. Sagittal is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://sagittal.org This document also currently reproduces some glyphs from the Unicode 6.2 code chart for the Musical Symbols range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1D100.pdf). These glyphs are the copyright of their respective copyright holders, listed on the Unicode Consortium web site here: http://www.unicode.org/charts/fonts.html 2 Version history Version 0.1 (2013-01-31) § Initial version. Version 0.2 (2013-02-08) § Added Tick barline (U+E036). § Changed names of time signature, tuplet and figured bass digit glyphs to ensure that they are unique. § Add upside-down and reversed G, F and C clefs for canzicrans and inverted canons (U+E074–U+E078). § Added Time signature + (U+E08C) and Time signature fraction slash (U+E08D) glyphs. § Added Black diamond notehead (U+E0BC), White diamond notehead (U+E0BD), Half-filled diamond notehead (U+E0BE), Black circled notehead (U+E0BF), White circled notehead (U+E0C0) glyphs. § Added 256th and 512th note glyphs (U+E110–U+E113). § All symbols shown on combining stems now also exist as separate symbols. § Added reversed sharp, natural, double flat and inverted flat and double flat glyphs (U+E172–U+E176) for canzicrans and inverted canons. -

Musical Staff: the Skeleton Upon Which Musical Notation Is Hung

DulcimerCrossing.com General Music Theory Lesson 7 Steve Eulberg Musical Staff [email protected] Musical Staff: The skeleton upon which musical notation is hung. The Musical Staff is comprised of a clef (5 lines and 4 spaces) on which notes or rests are placed. At one time the staff was made up of 11 lines and 10 spaces. It proved very difficult to read many notes quickly and modern brain research has demonstrated that human perception actually does much better at quick recall when it can “chunk” information into groups smaller than 7. Many years ago, the people developing musical notation created a helpful modification by removing the line that designated where “Middle C” goes on the staff and ending up with two clefs that straddle middle C. The treble clef includes C and all the notes above it. The Bass clef includes C and all the notes below it. (See Transitional Musical Staff): DulcimerCrossing.com General Music Theory Lesson 7 Steve Eulberg Musical Staff [email protected] Now the current musical staff has separated the top staff and the bottom staff further apart, but they represent the same pattern of notes as above, now with room for lyrics between the staves. (Staves is the plural form of Staff) DulcimerCrossing.com General Music Theory Lesson 7 Steve Eulberg Musical Staff [email protected] The Staves are distinct from each other by their “Clef Sign.” (See above) This example shows the two most commonly used Clef Signs. Compare the Space and Line names in the Historical example and this one. The information is now “chunked” into less than 7 bits of information (which turns out to be the natural limit in the human brain!) on each staff. -

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window. -

Tno, /W the EDITION of a QUARTET for SOLO DOUBLE

tNo, /w THE EDITION OF A QUARTET FOR SOLO DOUBLE BASS, VIOLIN, VIOLA, AND VIOLONCELLO BY FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH SELECTED WORKS BY J.S. BACH, N. PAGANINI S. KOUSSEVITZKY, F. SKORZENY, L. WALZEL AND OTHERS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Harry P. Jacobson, M.M. Denton, Texas May, 1982 Jacobson, Harry P., The Edition of a Quartet for Solo Double Bass, Violin, Viola, and Violoncello by Franz Anton Hoffmeister, a Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works by J.S. Bach, S. Koussevitsky, N. Paganini, F. Skorzeny, L. Walzel, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Double Bass Performance), May 1982, 68 pp.; score, 31 pp.; 11 illustrations; bibliography, 65 titles. A great amount of solo literature was written for the double bass in the latter half of the eighteenth century by composers working in and around Vienna. In addition to the many concertos written, chamber works in which the bass plays a solo role were also composed. These works of the Viennese contrabass school are an important source of solo literature for the double bass. A solo-quartet by Hoffmeister perviously unpublished was discovered by the author in the archives of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna. This work contributes to the modern solo repertoire for double bass, and has considerable musical merit. It is a well written work using. cleverly overlapped phrases, counterpoint and imitative writing, and effective juxtaposition of contrasting instrumentation. -

Port Na Bpúcaí Title Code 1 Altan 25Th Anniversary Celebration with The

Port na bPúcaí Title Code Aberlour's Save the last drop 9,95 1 Abbey Ceili Band Bruach at StSuiain 9,95 1 Afro Celt Sound System POD (CD & DVD) CDRW 116 18,95 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 1 - Sound Magic CDRW61 14,95 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 2 - Release CDRW76 14,95 1 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 3 - Further in time CDRW96 14,95 Afro Celt Sound System Anatomic CDRW133 16,95 Afro Celt Sound System Seed CDRWG111 Altan 25th Anniversary Celebration with the ALT001 16,95 2 RTE concert orchestra Altan Altan ( Frankie & Mairead ) GLCD 1078 16,95 Altan another sky... 724384883829 12,95 Altan Best of, The (2CDs) GLCD 1177 16,95 1 Altan The best of Altan - The Songs 7, 24354E+11 9,95 Altan Blackwater CDV2796 12,95 Altan Blue Idol, The CDVE961/ 8119552 16,95 Altan Finest, The CCCD100 8,95 Altan First ten years 1986-1995, The GLCD 1153 14,95 Altan Glen Nimhe - The Poison Glen COM4571 16,95 Altan harvest storm GLCD 1117 16,95 Altan horse with a heart GLCD 1095 16,95 Altan island angel GLCD 1137 16,95 1 Altan Local ground VERTCD069 19,95 Altan Runaway sunday CDV2836 12,95 Altan Red crow, The GLCD 1109 16,95 Altan The widening gyre 16,95 1 Ancient voice of Ireland Haunting Irish melodies 9,95 2 Anúna Anúna DANU21 9,95 1 Anúna Deep dead blue DANU020 14,95 Anúna Illumination DANU029 Anúna Invocation DANU015 14,95 Anúna Sanctus DANU025 14,95 Anúna Winter Songs DANU 16 14,95 Arcade Fire The subburbs 6,95 5 Arcady After the ball.. -

Adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents

.....••_•____________•. • adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents Ordering Information 2 Arabic * Middle Eastern 51 Order Blank 3 Jewish 52 About Ladyslipper 4 Alternative 53 Donor Discount Club * Musical Month Club 5 Rock * Pop 56 Readers' Comments 6 Folk * Traditional 58 Mailing List Info * Be A Slipper Supporter! 7 Country 65 Holiday 8 R&B * Rap * Dance 67 Calendars * Cards 11 Gospel 67 Classical 12 Jazz 68 Drumming * Percussion 14 Blues 69 Women's Spirituality * New Age 15 Spoken 70 Native American 26 Babyslipper Catalog 71 Women's Music * Feminist Music 27 "Mehn's Music" 73 Comedy 38 Videos 77 African Heritage 39 T-Shirts * Grab-Bags 82 Celtic * British Isles 41 Songbooks * Sheet Music 83 European 46 Books * Posters 84 Latin American . 47 Gift Order Blank * Gift Certificates 85 African 49 Free Gifts * Ladyslipper's Top 40 86 Asian * Pacific 50 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat'11-5) Ordering Information INFORMATION: 919-683-1570 (same as above) FAX: 919-682-5601 (24 hours'7 days a week) PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available. LP = record, CS = cassette, CD = com schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives pact disc. Some recordings are available only on LP Ladyslipper, Inc. -

What's New in Sibelius® Software

What’s New in Sibelius® Software versions 2018.1–2018.6 Legal Notices © 2018 Avid Technology, Inc., (“Avid”), all rights reserved. This guide may not be duplicated in whole or in part without the written consent of Avid. For a current and complete list of Avid trademarks visit: www.avid.com/legal/trademarks-and-other-notices Bonjour, the Bonjour logo, and the Bonjour symbol are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Thunderbolt and the Thunderbolt logo are trademarks of Intel Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. This product may be protected by one or more U.S. and non-U.S. patents. Details are available at www.avid.com/patents. Product features, specifications, system requirements, and availability are subject to change without notice. Guide Part Number 9329-65958-00 REV A 06/18 Contents Introduction . 1 New Features and Improvements in Sibelius 2018.6 . 1 New Features and Improvements in Sibelius 2018.4 . 1 New Features and Improvements in Sibelius 2018.1 . 1 System Requirements and Compatibility Information . 1 Conventions Used in Sibelius Documentation . 2 Resources. 3 New Features and Enhancements in Sibelius 2018.6. 4 Sibelius | First. 4 Single Installer and Application for Sibelius | First, Sibelius, and Sibelius | Ultimate . 4 Improved Layout for Grace Notes . 5 Improved Layout for Multiple Voices on a Single Staff . 6 Transposing Tied Notes in a Chord by Semitone . 6 New Features and Enhancements in Sibelius 2018.4. 7 New Naming Conventions for Sibelius Software . 7 Text Entry and Editing Across Multiple Staves . 7 Improvements to Transposing Individual Tied Notes in Chords .