JEMH Article WB Gambrill Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Romancing race and gender : intermarriage and the making of a 'modern subjectivity' in colonial Korea, 1910-1945 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9qf7j1gq Author Kim, Su Yun Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Romancing Race and Gender: Intermarriage and the Making of a ‘Modern Subjectivity’ in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Su Yun Kim Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Yoneyama, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Jin-kyung Lee Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Yingjin Zhang 2009 Copyright Su Yun Kim, 2009 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Su Yun Kim is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………...……… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Figures ……………………………………………….……………………...……. v List of Tables …………………………………….……………….………………...…... vi Preface …………………………………………….…………………………..……….. vii Acknowledgements …………………………….……………………………..………. viii Vita ………………………………………..……………………………………….……. xi Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. xii INTRODUCTION: Coupling Colonizer and Colonized……………….………….…….. 1 CHAPTER 1: Promotion of -

The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan Independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Dalei Jie University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Jie, Dalei, "The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 524. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Abstract How to explain the rise and fall of the Taiwan independence policy? As the Taiwan Strait is still the only conceivable scenario where a major power war can break out and Taiwan's words and deeds can significantly affect the prospect of a cross-strait military conflict, ot answer this question is not just a scholarly inquiry. I define the aiwanT independence policy as internal political moves by the Taiwanese government to establish Taiwan as a separate and sovereign political entity on the world stage. Although two existing prevailing explanations--electoral politics and shifting identity--have some merits, they are inadequate to explain policy change over the past twenty years. Instead, I argue that there is strategic rationale for Taiwan to assert a separate sovereignty. Sovereignty assertions are attempts to substitute normative power--the international consensus on the sanctity of sovereignty--for a shortfall in military- economic-diplomatic assets. -

Strategies for Parenting Children with Difficult Temperament

Strategies for Parenting Children with Difficult Temperament by Karen Stephens Children are born with an inborn temperament, a preferred style of relating to people and events. Temperament is indicated by behavior that clusters into three categories: easy, slow-to-warm up, and difficult. No category makes a child good or bad. They merely describe a child’s response patterns. Some children (approximately 10-20%) are born with “difficult temperament.” Traits include: high, often impulsive activity level; extra sensitive to sensory stimulation; overwhelmed by change in routines and new experiences; intense, inflexible reactions; easily distracted or incredibly focused; adapt slowly to change, not able to calm themselves well; irregular biological rhythms, such as hunger/sleep schedules; rapid, intense, mood swings resulting in acting out or withdrawing completely. Your discipline interactions can clue you into your child’s temperament. Parents struggling with difficult temperament say they continually remind and nag; name-call, yell, bribe, plead, make empty threats; give into power-struggles; feel as if their child “calls all the shots”or “rules the roost”; over-react; argue with co-parent over discipline; or give up trying to discipline at all. None of those characteristics make life easy, for kids or parents. But children with difficult temperament can learn to cope with their sensitivities. If they don’t learn, Your they can become confused, frustrated, and hopeless. In addition, they will most likely have to endure constant negative feedback which creates a vicious cycle of discouragement. discipline Children with difficult temperament do require extra time, guidance, and patience. But all children can be raised to be well-adjusted people with positive self esteem. -

Bab Ii Tinjauan Pustaka

BAB II TINJAUAN PUSTAKA A. DESKRIPSI SUBYEK PENELITIAN 1. SISTAR Sistar merupakan girlband yang berada di bawah naungan Starship Entertainment. Girlband yang debut pada tanggal 3 Juni 2010 ini beranggotakan Hyorin, Soyu, Bora, dan Dasom. Teaser debut Sistar yang berjudul Push Push rilis pada tanggal 1 Juni 2010, dan melakukan debut stage pertama kali di acara Music Bank (salah satu acara musik Korea Selatan) tanggal 4 Juni 2010 (http://www.starship- ent.com/index.php?mid=sistaralbum&page=2&document_srl=373, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 11.30 WIB). Gambar 2.1 Foto teaser debut Sistar berjudul Push Push Di tahun yang sama, tepatnya tanggal 25 Agustus, Sistar kembali mempromosikan single debut berjudul Shady Girl. Single ini semakin membuat nama Sistar dikenal oleh khalayak, dan menempati chart tinggi dibeberapa situs musik Korea Selatan. Tanggal 23 13 14 November, Sistar merilis Teaser MV untuk single baru berjudul How Dare You. Namun karena permasalahan perebutan perbatasan antara Korea Utara dan Korea Selatan, membuat MV untuk Single How Dare You sedikit terlambat dipublikasikan. Tepat seminggu, akhirnya pada tanggal 2 Desember MV tersebut rilis dan berhasil menempati urutan teratas di beberapa chart music seperti Melon, Mnet, Soribada, Bugs, Monkey3, dan Daum Musik. Dalam Melon Chart bulan Desember tahun 2010, Sistar menempati urutan ke empat dalam Top 100 (http://www.melon.com/chart/search/index.htm, diakses pada 26 oktober 2017 pukul 12.25 WIB). Sistar - Single How Dare You Gambar 2.2 Melon Chart Desember 2010 Untuk tahun 2011, Sistar kembali melebarkan sayapnya di dunia musik dengan membentuk sub-unit yang beranggotakan Hyorin dan Bora. -

Lanco Celebrate Romance, Bar Band Roots at Nashville Homecoming Concert

(12.9.18) - https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-country/lanco-hallelujah-nights-tour-review-766686/ Lanco Celebrate Romance, Bar Band Roots at Nashville Homecoming Concert Brandon Lancaster and his group mix covers with hits like “Greatest Love Story” on Hallelujah Nights Tour “Greatest Love Story” hitmakers Lanco capped the opening leg of their first headlining tour at Nashville’s Cannery Ballroom Friday night, bringing a combustible mix of romance and live-for-the-moment joy to a sold- out crowd of about 1,000 hometown fans. Having spent the summer on Dierks Bentley’s Mountain High Tour and then their own Hallelujah Nights run, the five-piece band — made up of frontman Brandon Lancaster, guitarist Eric Steedly, drummer Tripp Howell, bassist Chandler Baldwin and multi-instrumentalist Jared Hampton — showed why they’ve been earning a reputation as one of country’s most potent live acts. Lanco broke out in 2017 with the Double Platinum single “Greatest Love Story,” a freewheeling epic inspired by Lancaster’s own youth in nearby Smyrna, Tennessee, and followed up in 2018 with the propulsive heartbeat of “Born to Love You” — plus a CMA Awards nod for Vocal Group of the Year. Just before Friday night’s show, Steedly shared that the band will spend this week tracking their second LP with producer Jay Joyce (Eric Church, Brothers Osborne). But at the Cannery, Lanco — one of the 2019 CRS “New Faces” class — were focused on soaking up their journey so far, not looking ahead. “The last time we played in this building, it was a few floors up, to about 15 people,” Lancaster said toward the end of their hour-long set, referencing the cozy High Watt stage on the complex’s top floor. -

K-Pop Fandom in Lima,Perú

Wesleyan ♦ University K-POP FANDOM IN LIMA, PERÚ: VIRTUAL AND LIVE CIRCULATION PATTERNS By Stephanie Ho Faculty Advisor: Dr. Mark Slobin A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Middletown, Connecticut MAY 2015 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mark Slobin, for his invaluable guidance and insights during the process of writing this thesis. I am also immensely grateful to Dr. Su Zheng and Dr. Matthew Tremé for acting as members of my thesis committee and for their considered thoughts and comments on my early draft, which contributed greatly to the improvement of my work. I would also like to thank Gabrielle Misiewicz for her help with editing this thesis in its final stages, and most importantly for supporting me throughout our time together as classmates and friends. I thank the Peruvian fans that took the time to help me with my research, as well as Virginia and Violeta Chonn, who accompanied me on fieldwork visits and took the time to share their opinions with me regarding the Limeñan fandom. Thanks to my friends and colleagues at Wesleyan – especially Nicole Arulanantham, Gen Conte, Maho Ishiguro, Ellen Lueck, Joy Lu, and Ender Terwilliger – as well as Deb Shore from the Music Department, and Prof. Ann Wightman of the Latin American Studies Department. From my pre-Wesleyan life, I would like to acknowledge Francesca Zaccone, who introduced me to K-pop in 2009, and has always been up for discussing the K-pop world with me, be it for fun or for the purpose of helping me further my analyses. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Three Talks on Minjung Theology

THREE TALKS ON MINJUNG THEOLOGY HYUN Younghak The three talks on Minjung Theology that follow below were submitted to INTER-RELIGIO for publication by Paul Sye, former Director of the Institute for the Study of Religion and Theology in Seoul (see NEWS AND COMMUNICATIONS), and are reproduced here with the author’s permission. They were originally delivered on April 13, April 20, and November 4, 1982, at the James Memorial Chapel of the Union Theological Seminary in New York. After several frustrating attempts to edit the pieces independently of consultation with the author, it was decided to print them here just as they appeared in the original text. We think you will agree that the unpolished edge of Dr. Hyun’s language reflects the sense of immediacy as well as the sense of distance that minjung theologians feel in attempting to reach a western audience. Although the context is clearly Christian and missionary, the problems it raises suggest an altogether different base for interreligious dialogue with the Korean minjung than the ones traditionally generated from within academic circles. Lecture 1: MINJUNG: THE SUFFERING SERVANT AND HOPE PROLOGUE As I was preparing the lectures to be delivered at Union Theological Seminary as a Henry W. Luce Visiting Professor of World Christianity, and now as I stand in my Sunday best in from of you to deliver one of the lectures, I am overwhelmed by a feeling of myself being ridiculous and also looking ridiculous. There are three reasons for this: 1. The chair of this particular professorship appears so big and high that I have a feeling that my feet are dangling over the seat. -

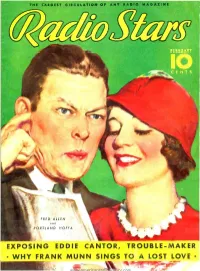

Exposing Eddie Cantor, Trouble -Maker Why Frank Munn Sings to a Lost Love

THE LARGEST CIRCULATION OF ANY RADIO MAGAZINE FRED ALLEN AND PORTLAND HOFFA EXPOSING EDDIE CANTOR, TROUBLE -MAKER WHY FRANK MUNN SINGS TO A LOST LOVE . www.americanradiohistory.com New Kind of Dry Rouge aCt y Ataiz.0 on ag cz'ary. ALL NIGMT f , ,d,u.,.,g,r.,,,, ,1,1 de, ,,,h, , . ra :°;'.r,;, NAIL 1,1_ How often you have noticed that most dry rouge seems to lose the i uiry of its color within an hour or so of its application. That is beeatse the sr.droucc particles are so coarse ve n texture, , that they simply, fall areuy from your skin. SAVAGE Rouge, as Your ,nse of touch will instantly tell you, is a great ,lead finer in restore and :miter thin ordinary rouge. Its particles being so infinitely line. adhere much more closely to the skin than rouge has ever clung before. In leer, SAVAGE Rouge, for this reason, clings so insistently, it seems to bee a part of the skin itself ... refusing to y eld, even to the savage caresses its tempting smoorhirers and poise- quickening color might easily invite. The price its ?Cc and the shades, to keep sour lips and cheeks in thrilling harmony, match perfects' drove of SAVAGE LIPSTICK . known as the o transparent-colored indelible lipstick that aer1.1,11y keeps lips seductively soft instead Of drain.e them as indelible lipstick usually does. Apply it rub it in, and delight i ,hiding your lips lusciously, lastingly tinted, yet utterly grease- less. Only :Cc .rid each or the tout hues is as vibrantly alluring, as completely intoxicating as a ¡oriole niche Everyone has found them so. -

Songliste Koreanisch (Juli 2018) Sortiert Nach Interpreten

Songliste Koreanisch (Juli 2018) Sortiert nach Interpreten SONGCODETITEL Interpret 534916 그저 널 바라본것 뿐 1730 534541 널 바라본것 뿐 1730 533552 MY WAY - 533564 기도 - 534823 사과배 따는 처녀 - 533613 사랑 - 533630 안녕 - 533554 애모 - 533928 그의 비밀 015B 534619 수필과 자동차 015B 534622 신인류의 사랑 015B 533643 연인 015B 975331 나 같은 놈 100% 533674 착각 11월 975481 LOVE IS OVER 1AGAIN 980998 WHAT TO DO 1N1 974208 LOVE IS OVER 1SAGAIN 970863기억을 지워주는 병원2 1SAGAIN/FATDOO 979496 HEY YOU 24K 972702 I WONDER IF YOU HURT LIKE ME 2AM 975815 ONE SPRING DAY 2AM 575030 죽어도 못 보내 2AM 974209 24 HOUR 2BIC 97530224소시간 2BIC 970865 2LOVE 2BORAM 980594 COME BACK HOME 2NE1 980780 DO YOU LOVE ME 2NE1 975116 DON'T STOP THE MUSIC 2NE1 575031 FIRE 2NE1 980915 HAPPY 2NE1 980593 HELLO BITCHES 2NE1 575032 I DON'T CARE 2NE1 973123 I LOVE YOU 2NE1 975236 I LOVE YOU 2NE1 980779 MISSING YOU 2NE1 976267 UGLY 2NE1 575632 날 따라 해봐요 2NE1 972369 AGAIN & AGAIN 2PM Seite 1 von 58 SONGCODETITEL Interpret 972191 GIVE IT TO ME 2PM 970151 HANDS UP 2PM 575395 HEARTBEAT 2PM 972192 HOT 2PM 972193 I'LL BE BACK 2PM 972194 MY COLOR 2PM 972368 NORI FOR U 2PM 972364 TAKE OFF 2PM 972366 THANK YOU 2PM 980781 WINTER GAMES 2PM 972365 CABI SONG 2PM/GIRLS GENERATION 972367 CANDIES NEAR MY EAR 2PM/백지영 980782 24 7 2YOON 970868 LOVE TONIGHT 4MEN 980913 YOU'R MY HOME 4MEN 975105 너의 웃음 고마워 4MEN 974215 안녕 나야 4MEN 970867 그 남자 그 여자 4MEN/MI 980342 COLD RAIN 4MINUTE 980341 CRAZY 4MINUTE 981005 HATE 4MINUTE 970870 HEART TO HEART 4MINUTE 977178 IS IT POPPIN 4MINUTE 975346 LOVE TENSION 4MINUTE 575399 MUZIK 4MINUTE 972705 VOLUME UP 4MINUTE 975332 WELCOME -

08-09 Stephenson Calendar

BEREA COLLEGE CONVOCATIONS STEPHENSON MEMORIAL CONCERT SERIES 2018–2019 Season 8:00 p.m. • Phelps Stokes Auditorium • Berea, KY ALL OF THESE EVENTS ARE OPEN TO THE PUBLIC AND FREE OF CHARGE Villalobos Brothers Corey Ledet The Villalobos Brothers masterfully blend SEPT and his FEB Zydeco Band elements of jazz, rock, classical and Mexican 13TH 14TH folk music to deliver a powerful message of Zydeco love, brotherhood and social justice. musician Corey Ledet remains true to his roots while infusing old and new styles into his own unique and versatile sound. Omer Quartet OCT Distinctive among today’s young string quartets, 4TH the award-winning Omer Quartet enthralls audiences with a wide range of classical repertoire from Beethoven to Schumann. Dervish An icon of traditional Irish music, Dervish have been enchanting audiences around the world MAR with their passionate vocals and dazzling 14TH instrumentals for many years. Farah Siraj NOV APR Red Molly Jordanian Celebrated for their virtuoso 15TH 11TH beautiful harmonies, Farah Siraj Red Molly skillfully weave fascinates together the various global threads of American audiences with music—from folk her original roots to bluegrass compositions, and from fusing Middle heartbreaking Eastern music, ballads to flamenco, jazz, honky Bossa nova and tonk. pop with lyrics in Arabic, Spanish and English. BEREA COLLEGE CONVOCATIONS B erea College students are expected to attend seven convocations each term except during their term of graduation and are also expected to familiarize themselves with the Convocation rules published in the Student Handbook. Convocations take place in Phelps Stokes Auditorium on Thursdays, unless otherwise indicated beforehand. -

Wherever You Go, There You Are: a Biographical Reconstruction Of

i Wherever You Go, There You Are: A Biographical Reconstruction of Korean Immigrants in the United States by Way of Germany Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Akademischen Grades eines Dr. phil., vorgelegt dem Fachbereich 02- Sozialwissenschaften, Medien und Sport der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz von Poo Lum Jong aus A-San, Südkorea Mainz 2018 i Tag des Prüfungskolloquiums: 17. April 2019 ii iii Contents Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 Research interest .................................................................................................................... 1 Research purpose .................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2. Historical and theoretical background ............................................................... 5 History of Korean guest workers in Germany and their second migration ............................ 5 General background............................................................................................................ 6 Push and pull factors in Korea and Germany ..................................................................... 8 Push and pull factors in Korea, Germany, and the US ..................................................... 10 Biography and Socialization ................................................................................................ 13 Biography ........................................................................................................................