Lochnagar Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Houston Houston

UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON MEDIA ALMANAC 2018-19 MEN'S GOLF UHCOUGARS.COM 2018-19 HOUSTON MEN'S GOLF CREDITS Executive Editor Jeff Conrad UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON DEPARTMENT OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS MISSION STATEMENT The University of Houston Department of Intercollegiate Athletics inspires excellence today while pre- paring leaders for life by fostering a culture, which challenges student-athletes to achieve their high- est academic, athletic and personal aspirations. CORE VALUES • Excellence • Integrity • Inclusivity • Loyalty • Accountability • Sportsmanship PRINCIPLES • To cultivate the highest quality sports programs, facilities and resources to build and maintain winning traditions • To provide a competition environment of high entertainment value for a loyal fan base with a commitment to sportsmanship and customer service • To attract and develop student-athletes who exhibit the qualities of intellectual growth, account ability, maturity, independence and leadership with the goal of building champions for life • To enrich the opportunity to earn an undergraduate degree by offering each student-athlete a quality educational, social and athletic experience • To ensure the department is in adherence with NCAA, Office of Civil Rights, American Athletic Conference and University rules and regulations to operatewith the highest degree of integrity • To exercise fiscal responsibility throughout the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics • To build and strengthen relationships throughout the University campus and the Houston community UNIVERSITY -

THE PLAYERS First-Timers Press Conference Wednesday, March 19, 2021

THE PLAYERS First-Timers Press Conference Wednesday, March 19, 2021 PLAYER BIOS Cameron Davis Birthplace: Sydney, Australia Residence: Seattle, Washington College: N/A How he qualified for THE PLAYERS: Top 125 in FedExCup standings from start of 2019-20 season through 2021 WGC-Workday Championship Fast Facts: • Surprisingly won the 2017 Australian Open at The Australian Golf Club after beginning the final round six strokes back of the lead. Held off the likes of Jason Day and Jordan Spieth to win his first professional tournament in his backyard. • Moved to Seattle after turning professional where he met girlfriend Jonika Melcher, whom he proposed to on April 21, 2019. They were married on September 5, 2020 in Seattle. • Best PGA TOUR finish: 3rd at 2021 The American Express Doug Ghim Birthplace: Des Plaines, Illinois Residence: Las Vegas, Nevada College: University of Texas How he qualified for THE PLAYERS: Non-exempt below the No. 10 position in FedExCup standings as necessary to fill the field to 154 players Fast Facts: • Was the 2018 Ben Hogan Award recipient (nation's best collegiate golfer) as a senior at the University of Texas. • Because he was a recipient of an AJGA ACE Grant, which gave him the financial means necessary to play a national golf schedule, Doug gives back to the AJGA Foundation. • Played the 2018 Masters (T50) as the runner-up of the 2017 U.S. Amateur. • Doug grew up playing municipal courses; he was not a member of a country club. He recalled playing with used clubs purchased off eBay. He said he didn’t open a box of new golf balls until he was about 16; even then they were free. -

Minutes AGM 2017

Scottish Golf Union Patron Her Majesty the Queen Argyll & Bute Golf Union Minutes of AGM Sunday 19th November 2017 at 11:00 In the Inveraray Inn - Inveraray The meeting convened at 11:00 at the Inveraray Inn, Inveraray, with President Ian Shaw in the chair. Present:- President I. Shaw, T. Mundie, G. Chalmers, G. Morrison, M. Sim, S Ellis, G. Bolton, C. McKirdy, W.McAdam, J MacMillan, I Ferguson & D Whyte Apologies: - Minutes:- The minutes of the last AGM were read and approved: Proposed by G. Morrison, and Seconded by I. Shaw. Matters arising:- None. President’s report:- Secretary: Graham Bolton, 17 Mount Pleasant Road, Rothesay, Bute, PA20 9HQ T 0772 062 7397 E [email protected] Scottish Golf Union Patron Her Majesty the Queen Argyll & Bute Golf Union Secretary’s Report:- Gentlemen The season began way back in January when Glencruitten’s Robert MacIntyre saw his hopes of securing back-to-back Australian Men’s Amateur titles for Scotland end at the semi- final stage in Melbourne. Secretary: Graham Bolton, 17 Mount Pleasant Road, Rothesay, Bute, PA20 9HQ T 0772 062 7397 E [email protected] Scottish Golf Union Patron Her Majesty the Queen Argyll & Bute Golf Union Having recovered from illness that forced his withdrawal from the Australian Master of the Amateurs earlier this month, the left-hander rediscovered his matchplay form to go on a superb run at Yarra Yarra Golf Club. MacIntyre, 20, was seeking to emulate his Scotland team-mate Connor Syme after the Drumoig player lifted the Australian Amateur title 12 months ago, becoming the third Scot in 13 years to be crowned champion. -

1 a CIRCUMSTANTIAL ACCOUNT of the COMPETITIONS for the PRIZES

Return to index A CIRCUMSTANTIAL ACCOUNT of the COMPETITIONS for the PRIZES given by the HIGHLAND SOCIETY IN LONDON, to the best Performers on the GREAT HIGHLAND BAGPIPE, from the year 1781. The Highland Society of London, of which one of the first Dukes in Scotland, was then President, being desirous that the ancient spirit of the Great Pipe, which in former times called the Clans in Scotland to war, should be revived, were pleased to order Annual Prizes to be played for, and to be adjudged to the best performers on that instrument, who should appear as candidates at the Falkirk Tryst. The first prize to be a set of new Pipes, made by Hugh Robertson, Edinburgh, and forty merks Scots money; the second prize thirty merks; and the third the like sum. Some gentlemen as a deputation from the Society at Glasgow, and the agent from Edinburgh, made their appearance at Falkirk, the day preceding that appointed for the competition. They met on the following morning, and adjourned to the Mason Lodge; when, after hearing an excellent Gaelic poem recited by an old grey-headed bard, which he composed for the occasion in the presence of a select company of ladies and gentlemen, thirteen competing Pipers, and the maker of the Prize Pipes, the deputation and the agent, proceeded to the election of a preses, and six gentlemen to be judges of the merits of the performers. The Preses chosen on this occasion, was universally allowed to be no only a very fine player himself, but one of the first judges of the instrument in Scotland; and one of the judges chosen from the Glasgow deputation, was likewise acknowledged to be an excellent performer on that warlike instrument, and every way qualified for determining on the merits of the candidates. -

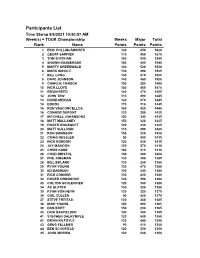

Participants List

Participants List Time Stamp 9/6/2021 10:50:57 AM Week(s) = TOUR Championship Weeks Major Total Rank Name Points Points Points 1 ERIC HOLLINGSWORTH 120 450 1620 2 GEOFF SAWYER 170 480 1575 3 TOM SHEEHAN 160 500 1545 4 SHAWN DAXBERGER 160 400 1540 5 MARTY GREENWALD 130 520 1530 6 MARK MICCILE 130 390 1525 7 BILL LONG 130 470 1505 8 DAVE JOHNSON 140 460 1500 9 CHARLIE TIERSCH 150 280 1480 10 NICK LLOYD 150 480 1475 11 BRIAN REED 140 470 1455 12 JOHN TEW 110 390 1445 13 DAVID MERIAN 120 370 1445 14 BOBO2 170 310 1445 15 RON VASCONCELLOS 160 420 1440 16 CONNOR DUPONT 120 380 1435 17 MITCHELL JOHANSON2 120 340 1435 18 MATT MULLANEY 150 320 1435 19 ROGER BOUSQUET 120 430 1425 20 MATT SULLIVAN 110 390 1425 21 RON SWANSON 150 320 1420 22 CRAIG RESSLER 50 500 1415 23 NICK KONDON 120 430 1415 24 JAY MAGOON 120 370 1410 25 CHRIS KANE 160 310 1410 26 CHAD BRISTOL 100 360 1400 27 PHIL KINGMAN 130 390 1385 28 BILL BOLAND 130 250 1385 29 RYAN YOUNG 130 470 1380 30 ED BABINSKI 100 440 1380 31 RICH CONNOR 130 430 1380 32 ROGER DONOGHUE 140 390 1380 33 COLTON SCHLEICHER 120 350 1380 34 AC SLATER 130 280 1380 35 RYAN VON HEYN 130 320 1375 36 GAIL CULLEN 90 420 1370 37 STEVE FREITAS 120 360 1365 38 MIKE YOUNG 120 290 1365 39 DAN BRITT 150 230 1365 40 DICK BACHELDER 120 400 1355 41 STEPHEN DALRYMPLE 120 500 1350 42 BRIAN KILFOYLE 120 440 1350 43 GREG FELLMER 90 410 1350 44 BEN SCHOFIELD 120 350 1350 45 JOHN MORRIS 120 330 1350 46 RYAN DUGAN 100 330 1350 47 JOE NEAZ 120 320 1350 48 JENN SULLIVAN 120 300 1350 49 DONNA SULLIVAN 110 400 1345 50 CHAD MEYER 120 -

Horsey Leads After Course Record 9-Under-Par 1St Round

OFFICIAL ORDER OF PLAY FRIDAY 5 FEBRUARY 2021 Royal Greens Golf & Country Club HORSEY LEADS AFTER COURSE RECORD 9-UNDER-PAR 1ST ROUND Spectators should note that by entering the venue a ball strike from a stray shot is a possibility. Spectators 12 RETAIL must therefore maintain vigilance for CAR PARK shouts of ‘Fore’. In the event of a ‘Fore’ shout spectators should crouch down and protect their head and face. TOURNAMENT 11 PERFORMANCE BUBBLE CENTRE SCHOOL 13 10 CAR VIP ENTRANCE PARK SHORT-GAME 2 & TEMPERATURE CHECK PRACTICE In the event of inclement weather this sign CAR PARK 2 will appear on all of the scoreboards. If MEDIA ENTRANCE CLUBHOUSE OVERFLOW play is suspended a siren will sound. You & TEMPERATURE CHECK TOURNAMENT must seek shelter immediately. Avoid open BUBBLE PUTTING areas, hilltops, high places, isolated trees, CLUBHOUSE ENTRANCE GREEN golf carts and wire fences. In the event of & TEMPERATURE CHECK an emergency evacuation please listen carefully for announcements and follow HOSPITALITY ENTRANCE PRACTICE the instructions given by Officials. & TEMPERATURE CHECK RANGE 2 3 ARAMCO OBSERVATION DECK VIP HOSPITALITY 1 PIF PAVILION TOURNAMENT 18 TOURNAMENT BUBBLE BUBBLE 14 9 VIEWING PLATFORM CAR PARK 1 TOURNAMENT BUBBLE DROP-OFF / COLLECTION HOSPITALITY BUBBLE HOSPITALITY TV PARKING & SCREENING HOSPITALITY BUBBLE COMPOUND BUBBLE 8 4 ROYAL MAJLIS HOSPITALITY LEADERBOARD BUBBLE 5 BIG SCREEN TOURNAMENT MEDICAL HQ TOURNAMENT 7 BUBBLE BUBBLE MAINTENANCE COMPOUND 17 6 HOSPITALITY BUBBLE 15 TOURNAMENT BUBBLE 16 COVID-19 Face coverings MUST be worn at all Maintain social distancing Use hand sanitizer regularly Wash your hands for 20 seconds times indoors and in outdoor areas at all times - available across the site with soap as often as possible where social distance is difficult COVID-19 Game Start 1st +/- Game Start 1st +/- No. -

2021 MEDIA GUIDE MARCH 24-28, 2021 AUSTIN COUNTRY CLUB Table of Contents

2021 MEDIA GUIDE MARCH 24-28, 2021 AUSTIN COUNTRY CLUB Table of Contents Format Overview and Glossary .........................................................2 2001 American Express Championship ...................................... 151 Schedule of Events ............................................................................3 2000 American Express Championship ...................................... 152 Media Facts ................................................................................... 4-6 1999 American Express Championship ...................................... 153 Tournament Officials .........................................................................7 FedEx St. Jude Invitational Facts ................................................ 154 2021 Official Scorecard .....................................................................8 2020 FedEx St. Jude Invitational ................................................. 155 4-Year Ranking of Holes at Austin Country Club .............................8 2019 FedEx St. Jude Invitational ................................................. 156 Scoring Averages at a Glance (2016-19) ..........................................9 2018 Bridgestone Invitational ...................................................... 157 Purse Breakdown...............................................................................9 2017 Bridgestone Invitational ...................................................... 158 History at a Glance ........................................................................ -

Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1

BMW PGA Championship Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1 Round 2 Game Time Tee Game Time Tee Name Country Attachment 1 07:35 1 30 11:45 9 Nacho ELVIRA ESP Oliver FISHER ENG Centurion Club Ross FISHER ENG 2 07:45 1 31 11:55 9 Guido MIGLIOZZI ITA Matthias SCHWAB AUT Schladming GC Nicolas COLSAERTS BEL Anahita - Mauritius 3 07:55 1 32 12:05 9 Julian SURI USA Grant FORREST SCO Craigelaw GC Fabrizio ZANOTTI PAR 4 08:05 1 33 12:15 9 Ashun WU CHN Shuangshan GC Graeme STORM ENG Stephen GALLACHER SCO Kingsfield Golf Centre 5 08:15 1 34 12:25 9 Haotong LI CHN Min Woo LEE AUS Royal Fremantle Kristoffer BROBERG SWE 6 08:25 1 35 12:35 9 Julien GUERRIER FRA Golf de la prée La Rochelle Søren KJELDSEN DEN The Scandinvian Dean BURMESTER RSA Mont Choisy Le Golf 7 08:35 1 36 12:45 9 Sean CROCKER USA Chris PAISLEY ENG Jeunghun WANG KOR 8 08:45 1 37 12:55 9 Thomas AIKEN RSA The Abaco club Scott JAMIESON SCO Kiradech APHIBARNRAT THA Singha 9 08:55 1 38 13:05 9 Alexander BJÖRK SWE Vaxjo GK Ashley CHESTERS ENG Hawkstone Park Joakim LAGERGREN SWE 10 09:05 1 39 13:15 9 Lucas HERBERT AUS Commonwealth GC Joël STALTER FRA Paris International GC Jorge CAMPILLO ESP Norba Club de Golf de Caceres 11 09:15 1 40 13:25 9 Richie RAMSAY SCO The Renaissance Club Jordan SMITH ENG Bowood Alvaro QUIROS ESP BMW PGA Championship Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1 Round 2 Game Time Tee Game Time Tee Name Country Attachment 12 07:35 9 21 11:55 1 Edoardo MOLINARI ITA Edoardo Molinari Golf Academy Victor DUBUISSON FRA Golf Old Course Cannes Mandelieu Jack SINGH BRAR ENG Remedy Oak 13 07:45 -

Minute of Meeting Held in the Isle of Mull Hotel and Spa, Craignure, Isle of Mull on Friday 16 September 2016 at 8.30Am

Minute of Meeting held in the Isle of Mull Hotel and Spa, Craignure, Isle of Mull on Friday 16 September 2016 at 8.30am. PRESENT Cllr James Stockan (Chair), Orkney Council Member (by tele-conference) Cllr John Mackay (in the Chair), Comhairle nan Eilean Siar Member Cllr Audrey Sinclair, The Highland Council Member Cllr Robert Macintyre, Argyll and Bute Council Cllr Graham Leadbitter Mr Okain Maclennan, Non-Councillor Member Prof David Gray, Non-Councillor Member Mr Wilson Metcalfe, Non-Councillor Member IN ATTENDANCE Mr Ranald Robertson, Partnership Director Mr Frank Roach, Partnership Manager Mr Neil MacRae, Partnership Manager Mrs. Nicola Moss, Moray Council Mr Gavin Barr, Orkney Islands Council Mr Iain Mackinnon, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar Mr Malcolm Macleod, The Highland Council Mrs. Moya Ingram, Argyll and Bute Council Mr Fergus Murray, Argyll and Bute Council Mr Tony Jarvis, HIE Ms Pip Farman, NHS Highland Mr. Fraser Grieve, SCDI APOLOGIES Cllr John Cowe, Moray Council Mr Mike Mitchell, Partnership Treasurer CONSTITUTION As the Chair was participating by remote link it was agreed that Cllr. John Mackay would Chair the meeting. Tribute: Mr Duncan The Chair referred to Mr Duncan Macintyre who had recently passed away. Mr Macintyre Macintyre had been a member of HITRANS over many years and had served as Chair from 2007 – 2012. The Chair paid tribute to Mr Macintyre’s contribution to the work of HITRANS and extended his condolences to Mr Macintyre’s family. MINUTES Minute of Meeting 1 The Minute of Meeting of 15 April 2016 was approved. of 28 June 2016 Matters Arising 2 Mr Ranald Robertson indicated that, with reference to item 7 (3), a response from the Minister for Transport had not yet been received. -

Si Woo Kim Brooks Koepka Jon Rahm Brian Harman Branden Grace

Brooks Koepka Si Woo Kim Billy Horschel Chan Kim Gfunk 0 0 0 0 0 Jon Rahm Brian Harman Max Homa Wade Ormsby Carl 2 0 0 0 0 0 Bryson DeChambeau Bubba Watson Branden Grace Zach Zaback Tracey 0 0 0 0 0 Rory McIlroy Christiaan Bezuidenhout Stewart Cink Guido Migliozzi Glenis 0 0 0 0 Kyle 0 Daniel Berger Tom Hoge Bo Hoag Westmoreland Megan 0 0 0 0 0 Schaffle Lee Westwood Ryan Palmer Sebastian Munoz Dan Freeman 0 0 0 0 0 Justin Thomas Adam Scott Ian Poulter J.J. Spaun Timmy D 0 0 0 0 Mackenzie 0 Collin Morikawa Martin Kaymer Matthew Wolff Hughes James Cook 0 0 0 0 0 Webb Simpson Gary Woodland Brendon Todd Peter Malnati John Parker 0 0 0 0 0 Dustin Johnson Kevin Na Kevin Streelman Martin Laird Dale Young 0 0 0 0 0 Tony Finau Matt Wallace Kevin Kisner Jimmy Walker Jay 1 0 0 0 0 0 Jordan Spieth Charley Hoffman Jhonattan Vegas Tyler Strafaci KD 0 0 0 0 0 Patrick Reed Sungjae Im Cameron Champ Cameron Young Justin 0 0 0 0 0 Patrick Cantlay Matt Kuchar Chez Reavie J.T. Poston T&D 0 0 0 0 0 Viktor Hovland Tommy Fleetwood Charl Schwartzel Bernd Wiesberger Dianna 2 0 0 0 0 0 Hideki Matsuyama Joaquin Niemann Zach Johnson Kyoung-Hoon Lee Grant 2 0 0 0 0 0 Scottie Scheffler Harris English Carlos Ortiz Wyndham Clark Justin 2 0 0 0 0 0 Matthew Phil Mickelson Fitzpatrick Sunghoon Kang Henrik Stenson Carl 0 0 0 0 0 Will Zalatoris Sam Burns Brendan Steele Paul Barjon Donovan 0 0 0 0 0 Paul Casey Sergio Garcia Adam Hadwin Wilco Nienaber Grant 0 0 0 0 0 Jason Kokrak Marc Leishman Robert MacIntyre Jordan Smith James Cook 2 0 0 0 0 0 Tyrrell Hatton Cameron Smith Matt Jones Lanto Griffin Dianna 0 0 0 0 0 Rafael Cabrera Corey Conners Louis Oosthuizen Russell Henley Bello Kendal 0 0 0 0 0 Abraham Ancer Garrick Higgo Erik Van Rooyen Dylan Frittelli Ceba 0 0 0 0 0 Francesco Justin Rose Shane Lowry Molinari Victor Perez Mitchell 0 0 0 0 0. -

Graduation Day for Jordan

£1.00 Alfred Dunhill Links Championship Daily News & Order of Play ROUND 3, SATURDAY 28 SEPTEMBER, 2019 GRADUATION DAY FOR JORDAN Matthew Jordan was invited to play in the Alfred Dunhill Links Champiionship and now the 23-year-old Englishman leads at the halfway stage – and behind him a trio of Scots are chasing a first home win since Colin Montgomerie in 2005 atthew Jordan Scottish galleries came for three of to get carried away as today he PRO LEADERS moved confidently their own: Hill, Russell Knox and will be playing Carnoustie, the up in class from Richie Ramsay, who all strength- toughest of the three courses. Matthew Jordan -14 the Challenge Tour ened their challenge and offer the "Whatever my position right Matthew Southgate -13 Mto take the halfway lead into prospect of a first home win since now, it's probably slightly higher Calum Hill -13 today’s third round of the Colin Montgomerie in 2005. than those that have started on Joakim Lagergren -13 Alfred Dunhill Links Hill, 24, who is currently No 1 Carnoustie. After three rounds, I Championship. on the Challenge Tour, is from think you can look at your posi- TEAM LEADERS The 23-year-old from the Wirral nearby Kirkcaldy. He said: "It’s tion a bit better and judge what Henson/Botham -21 shot a 64 on the Old Course for a always nice to be at home and play you need to do for the final day.” Jamieson/Foley -21 36-hole score of 14-under-par and in front of family and friends and In a congested leaderboard, Rock/McFadden -20 a one-shot lead over Scotland’s it's even better that I played well Justin Rose is two behind after a Sharma/van Zyl -20 Calum Hill, England’s Matthew and they can enjoy themselves 64 at Kingsbarns, had an eagle and Southgate and Joakim Lagergren because of that.” nine birdies, but it could have of Sweden. -

Justin Rose Shane Lowry Francesco Molinari Victor Perez Jordan Smith

Brooks Koepka Si Woo Kim Billy Horschel Chan Kim Gfunk 870 James Cook 852 69 73 71 69 282 71 75 70 74 290 74 75 74 75 298 76 77 76 77 306 Jon Rahm Brian Harman Max Homa Wade Ormsby Carl 2 854 Glenis 853 69 70 72 67 278 72 71 71 72 286 76 73 76 73 298 72 74 73 71 290 Bryson DeChambeau Bubba Watson Branden Grace Zach Zaback Tracey 862 Carl 2 854 73 69 68 77 287 72 67 77 76 292 72 70 74 67 283 75 72 75 72 294 Rory McIlroy Christiaan Bezuidenhout Stewart Cink Guido Migliozzi Glenis 853 Kendal 855 70 73 67 73 283 72 70 70 76 288 73 72 74 75 294 71 70 73 68 282 Kyle Daniel Berger Tom Hoge Bo Hoag Westmoreland Megan 867 Justin 2 858 71 72 72 68 283 72 71 76 72 291 78 78 78 78 312 66 73 78 76 293 Schaffle Lee Westwood Ryan Palmer Sebastian Munoz Dan Freeman 871 Grant 859 69 71 72 71 283 71 73 71 77 292 76 74 76 74 300 71 77 71 77 296 Justin Thomas Adam Scott Ian Poulter J.J. Spaun Timmy D 865 Tracey 862 73 69 71 73 286 70 75 71 73 289 74 71 68 77 290 77 75 77 75 304 Mackenzie Collin Morikawa Martin Kaymer Matthew Wolff Hughes James Cook 852 T&D 865 75 67 70 70 282 77 68 69 73 287 70 68 73 74 285 73 67 68 77 285 Webb Simpson Gary Woodland Brendon Todd Peter Malnati John Parker 892 Timmy D 865 79 73 79 73 304 74 71 73 74 292 78 71 78 71 298 75 76 75 76 302 Dustin Johnson Kevin Na Kevin Streelman Martin Laird Dale Young 871 Megan 867 71 73 68 74 286 77 73 77 73 300 71 69 72 73 285 74 76 74 76 300 Tony Finau Matt Wallace Kevin Kisner Jimmy Walker Jay 1 889 Gfunk 870 74 76 74 76 300 74 74 74 74 296 73 73 72 75 293 74 72 77 80 303 Jordan Spieth Charley Hoffman Jhonattan Vegas Tyler Strafaci KD 875 Dale Young 871 77 69 68 72 286 72 71 75 76 294 75 69 75 76 295 78 78 78 78 312 Patrick Reed Sungjae Im Cameron Champ Cameron Young Justin 875 Dan Freeman 871 72 73 74 67 286 72 72 69 76 289 76 75 76 75 302 72 78 72 78 300 Patrick Cantlay Matt Kuchar Chez Reavie J.T.